Yet, Czerny was more than just a teacher of technique. He was a visionary who understood the evolving demands of the piano and the pianist, helping to shape the very vocabulary of modern piano playing.

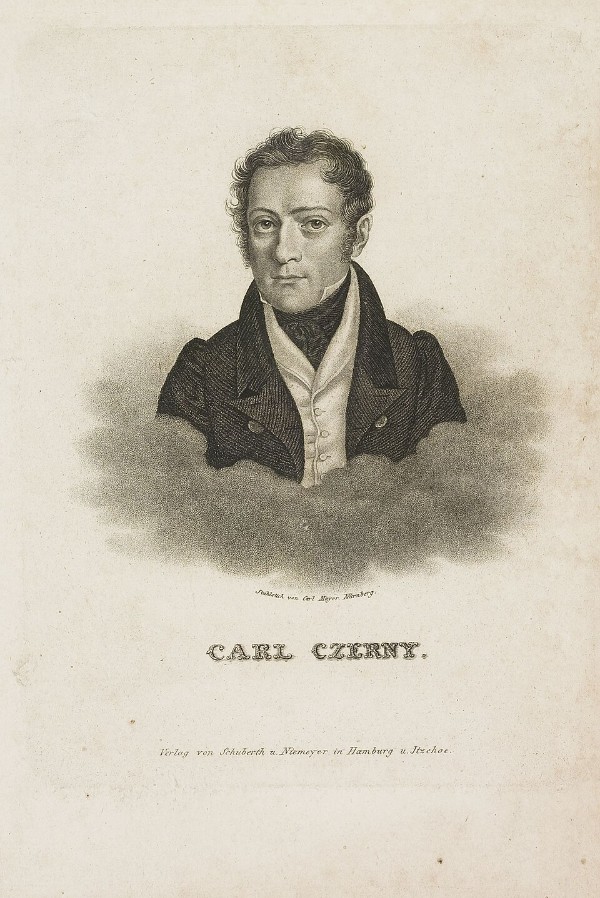

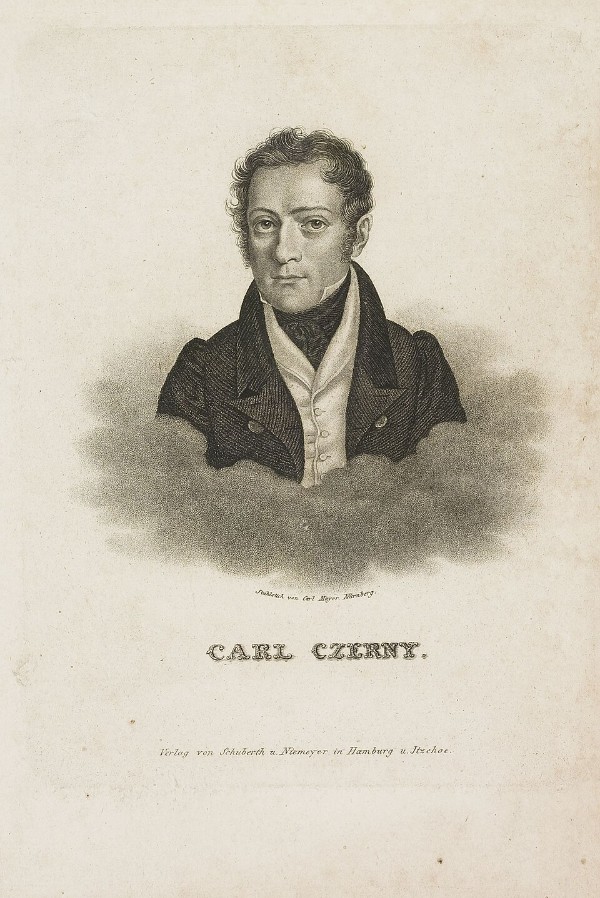

The young Carl Czerny

The predominant view of Czerny at the end of the 20th century as a pedagogue churning out a seemingly endless stream of uninspired works was circulated by Robert Schumann. However, this cavalier dismissal of Czerny was not uniformly shared.

Czerny was a musical bridge between the Classical and Romantic eras, most notably as a student of Ludwig van Beethoven and later as the teacher of Franz Liszt. Beethoven considered Czerny the favoured interpreter of his keyboard works, and Czerny equipped Liszt with the polish and finesse to embark on his pianistic conquest of the world.

To celebrate Czerny’s birthday on 21 February 1791, let’s explore his fascinating trajectory from studying under Ludwig van Beethoven to teaching the young Franz Liszt.

A Prodigy Emerges

Carl Czerny was, without doubt, an extraordinary child prodigy. He received his first lessons from his father at the age of three. According to his autobiography, he studied Bach, Clementi, and similar works… ‘as my father, far from wanting to train me to become a superficial concert player, tried to improve my skill in sight-reading and my musical sense.’ (Czerny, Recollections From My Life)

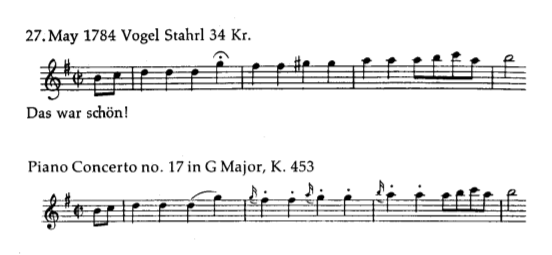

At any rate, Carl progressed rapidly, and by the age of ten he was able to play cleanly and fluently nearly everything of Mozart and Clementi. Initially, he played piano recitals in his parents’ home, and made his first public appearance in 1800, performing Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 24 in C minor.

Studies with Beethoven

Carl Czerny

Young Czerny was first introduced to Ludwig van Beethoven at the age of only eight. The first pianistic encounter, however, took place at Beethoven’s home in 1801. The visit was arranged by the composer and violinist Wenzel Krumpholz, and Czerny recalls.

“I had to play something right away, and since I was too bashful to start with one of his works, I played the great C-major concerto by Mozart. Beethoven soon took notice, moved close to my chair, and played the orchestral melody with his left hand whenever I had purely accompanying passages.” (Czerny, Recollections From My Life)

Beethoven then asked Czerny to play his recently published Pathétique Sonata and the accompaniment to Adelaide. Beethoven was suitably impressed and declared that he would accept the boy as his pupil. As such, Carl took lessons with Beethoven from 1801 to 1803 about twice a week, and sporadically until 1804.

Czerny describes the lessons as “consisting of scales and technique at first, then progressing with the stress on legato technique throughout.” On Beethoven’s recommendations, Prince Lichnowsky engaged Carl at the age of 13 to play Beethoven’s compositions for him, “all of which Carl knew by memory insofar as they had already been composed.” (Czerny, Recollections From My Life).

Czerny’s autobiography and letter are important documents describing Beethoven during this period. He was the first to report symptoms of Beethoven’s deafness, several years before the matter became public.

Czerny highly admired Beethoven’s facility at improvisation, his expertise at fingering, the rapidity of his scales and trills, and his restrained demeanour while performing.

In turn, Beethoven selected Czerny as pianist for the premiere of his Piano Concerto No. 1 in 1806 and, at the age of 21, in February 1812, Czerny gave the Vienna premiere of Beethoven’s “Emperor Piano Concerto.”

In his early teens, Czerny began to compose, with his first published compositions appearing in 1806. He composed with astounding energy, and when all was said and done, left a legacy of around 1,000 compositions and treatises on almost all aspects of pianism at the time.

Czerny decided against international concert tours and instead got started on a highly successful teaching career. Apparently, he taught up to twelve lessons a day in the homes of Viennese nobility, and his star students included Theodor Döhler, Stephen Heller, Anna Sick, Ninette de Belleville, and a very young Franz Liszt.

Talent in the Rough

One morning in 1819, Czerny’s most famous student would appear at his doorstep. As he recalled, “A man brought a small boy about eight years of age to me and asked me to let that little fellow play for me. He was a pale, delicate-looking child and while playing, he swayed on the chair as if drunk, so that I often thought he would fall to the floor.”

“Moreover, his playing was completely irregular, careless, and confused, and he had so little knowledge of correct fingering that he threw his fingers over the keyboard in an altogether arbitrary fashion. Nevertheless, I was amazed by the talent with which Nature had equipped him.”

“The father told me that his name was Liszt… and that up to this time he himself had taught his son. He was now asking me whether I would take charge of his little boy beginning the following year when he would come to Vienna. Of course, I gladly assented…” (Czerny, Recollections From My Life)

Training a Prodigy

Berlioz, Czerny and Liszt

Once piano lessons started in earnest, Czerny quickly confessed that he had never before seen such an eager, talented, or industrious student. Within weeks, Liszt was able to play the scales in all keys with a masterful fluency, and the intensive study of Clementi’s sonatas instilled in him a firm feeling for rhythm and taught him beautiful touch and tone, correct fingering, and proper musical phrasing.

After a year’s worth of lessons, Czerny allowed Liszt to perform publicly, and he apparently aroused a degree of enthusiasm in Vienna that few artists have equalled. Unfortunately, Czerny reports, “just when Liszt had reached a most fruitful stage in his studies, his father wished for great pecuniary gain and went on tour, first to Hungary and ultimately to Paris and London.” (Czerny, Recollections From My Life)

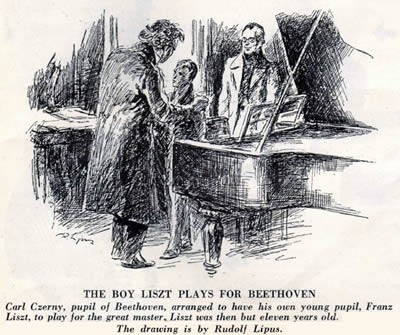

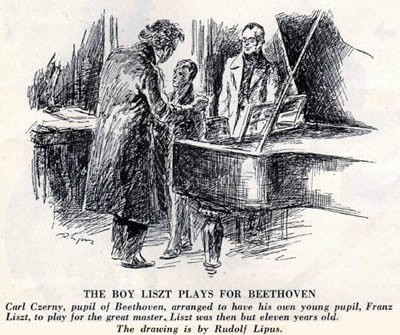

During his time of study with Carl Czerny, the 11-year-old Liszt was apparently introduced to Beethoven himself. Since Beethoven had an aversion against prodigies, he had refused to see Liszt for a long time. Finally, it was Czerny who convinced him.

Liszt Before Beethoven

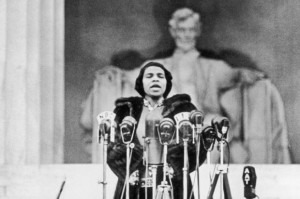

Franz Liszt reports, “Beethoven was sitting by the window at a long narrow table working. For a moment he looked at us with a serious face, said a couple of quick words to Czerny but turned silent as my dear teacher signalled to me to go to the piano.”

“First I played a small piece by Ries. When I had finished Beethoven asked if I could play a fugue by Bach. I chose the C-minor fugue from The Well-Tempered Clavier. Can you transpose this fugue? Beethoven asked.

Fortunately I could. After the final chord I looked up. Beethoven’s deep glowing eyes rested upon me, but suddenly a light smile flew over his otherwise serious face. He approached me and stroked me several times over my head with affection.

Suddenly my courage rose: “May I play one of your pieces?” I asked with audacity. Beethoven nodded with a smile. I played the first movement of his C major piano concerto.

When I had finished Beethoven stretched out his arms, kissed me on my forehead and said in a soft voice: You go on ahead. You are one of the lucky ones! It will be your destiny to bring joy and delight to many people and that is the greatest happiness one can achieve.” (Beethoven, Impressions by his Contemporaries).

Anecdote and Evidence

That particular meeting, according to most scholars, did probably take place, but some of the dramatic elements, like the kiss and prophecy, might well have been embellished or reshaped by later storytelling.

Liszt performed several of Czerny’s compositions as part of his repertoire, and he dedicated his twelve Transcendental Etudes to Czerny as well. Subsequently, he invited Czerny to collaborate on the Hexaméron, a collaborative work commissioned by Princess Cristina Trivulzio Belgiojoso in 1837.

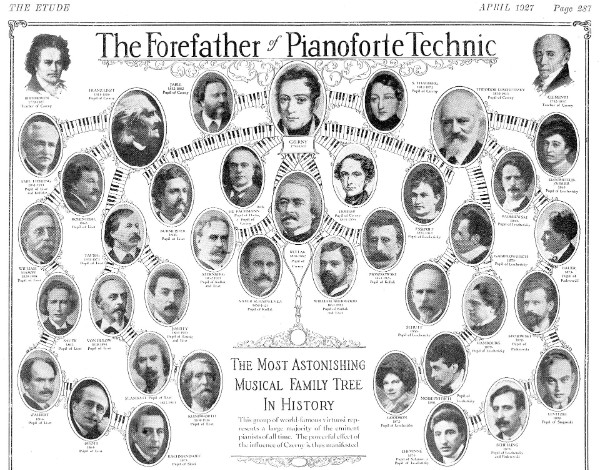

Father of Modern Pianism

By passing the legacy of Beethoven to Liszt, Czerny established himself as a father of modern piano technique for subsequent generations of pianists. The list of his piano descendants is vast, and ranges from Leschetizky, Prokofiev, and Arrau, to Cziffra, Barenboim, Rachmaninoff and Fleisher.

Over the last few decades, a substantial amount of research and re-evaluation of Carl Czerny has taken place, helping us to move beyond his traditional image as a composer of dry technical exercises. Finally, it seems, musicology has taken up the suggestion of Johannes Brahms who wrote in a letter to Clara Schumann:

“I certainly think Czerny’s large pianoforte course Op. 500 is worthy of study, particularly in regard to what he says about Beethoven and the performance of his works, for he was a diligent and attentive pupil… Czerny’s fingering is particularly worthy of attention. In fact I think that people today ought to have more respect for this excellent man.”