By Georg Predota, Interlude

The Farmer’s Daughter

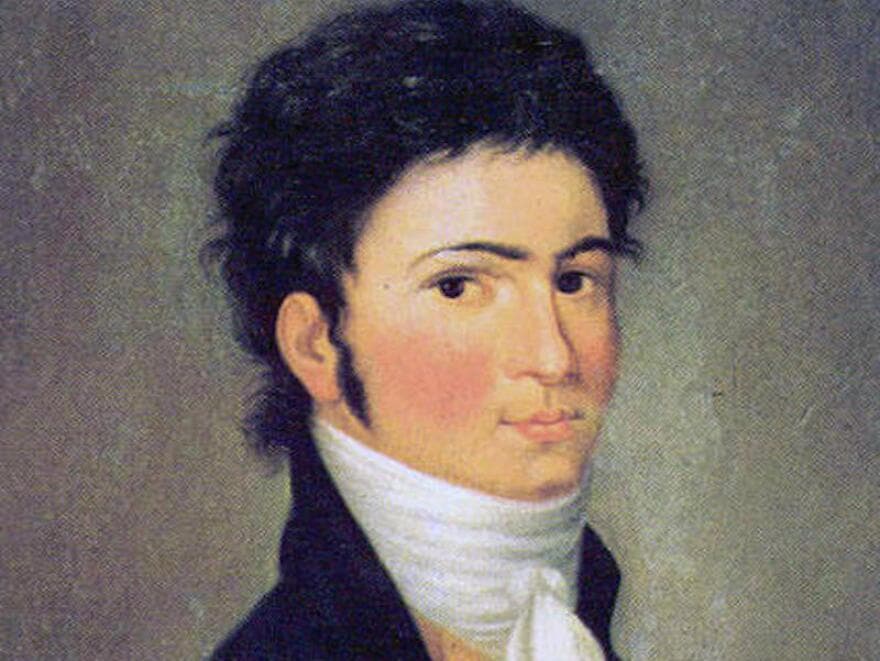

Beethoven in 1801

Beethoven’s landlord had a reputation for drunkenness, and for skirting the wrong side of the law. However, he also had a remarkably beautiful daughter, who had also managed to gain a bit of a reputation. A delightful anecdote reports that Beethoven was greatly captivated by her beauty, and made it a habit to stop his walk and gaze at her when she was working in the farmyard or the field. The farmer’s daughter, however, openly laughed at his clumsy advances.

However, the story isn’t quite finished, as the farmer was arrested and imprisoned for fighting in public. Hoping to impress the beautiful daughter, Beethoven went to the magistrate as an eyewitness to obtain his release. However, other witnesses came forward and refuted Beethoven’s telling of events, with the result that the farmer was forced to stay in jail.

Egyptian Hieroglyphs

Theater an der Wien

Beethoven, it is said, became very angry and abusive and was in danger of being arrested himself. A number of friends came to Beethoven’s aid, and convinced the magistrate of Beethoven’s position in society, his influence, and the power of his aristocratic friends. Having thus escaped jail, Beethoven set to work and drafted parts of a concerto for piano and orchestra in C minor.

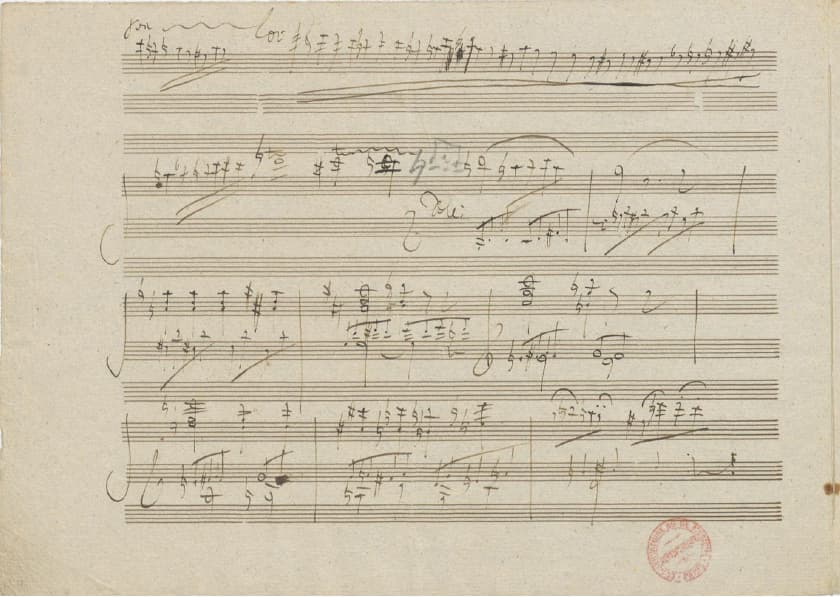

And while the inspiration might well have been Beethoven’s infatuation and ultimate rejection by a farmer’s daughter, the work was still unfinished when Beethoven presented it to the public almost three years later. Ignaz von Seyfried, the new conductor at the Theater an der Wien agreed to turn pages for Beethoven, and he reports, “I saw almost nothing but empty leaves,” he wrote, “at most on one page or another a few Egyptian hieroglyphs wholly unintelligible to me and scribbled down to serve as clues for him.”

As Seyfried reports, “Beethoven played nearly all of the solo part from memory since, as was so often the case, he had not had time to put it all down on paper. He gave me a secret glance whenever he was at the end of one of the invisible passages, and my scarcely concealable anxiety not to miss the decisive moment amused him greatly.” It took Beethoven another year to write out the piano part, and the work first appeared in print in 1804.

First Concerto Maturity

Ignaz von Seyfried

It has been suggested that the C-minor concerto is the first of his five piano concertos that sound like mature Beethoven. But what is more, it also reflects an important advance in piano technology as the range of the instrument had been expanded beyond the standard five-octave span.

The opening “Allegro con brio” pays homage to Mozart’s famous C-minor concerto (K. 491) by imitating the intricate interplay between soloist and orchestra and by launching into a further sparkling development in the coda. Singing with quiet nobility, the piano initiates the “Largo” movement. Imaginative orchestration creates a hushed mood in the remote key of E major and after a magical dialogue between the piano and orchestra, the movements conclude with a typical Beethovenian fortissimo exclamation.

Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 3 – original score

Less ornate and more muscular, the concluding “Rondo-Allegro” returns us to the minor key, with a pair of principal themes introduced by the soloist. Alternating passages of exuberant humour and blunt drama the movement irresistibly accelerates with the orchestra providing a high-spirited conclusion.

No comments:

Post a Comment