by Georg Predota, Interlude

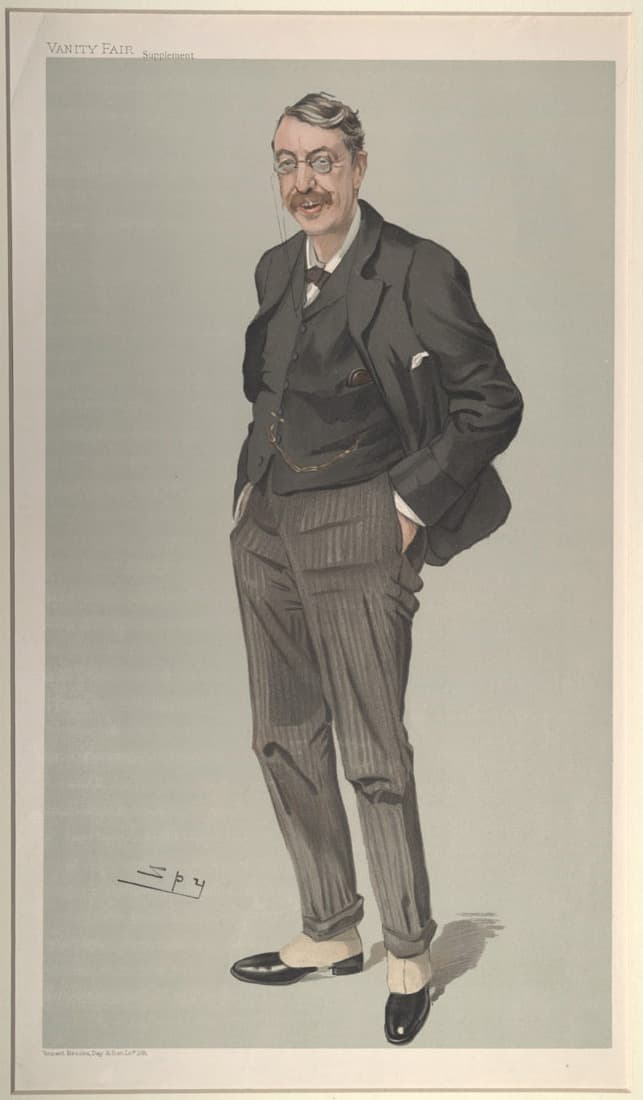

As a composer, Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924) might not be a household name, but he is remembered as a teacher of several generations of British composers at the RCM and Cambridge University. However, there is a clear disconnect between how he was celebrated in his day, and how posterity has decided to look at him.

Charles Villiers Stanford

Villiers Stanford was highly lauded during his lifetime as an exceptional composer of large works for chorus and orchestra, and he received a knighthood on the occasion of King Edward VII’s coronation. Posterity, however, has been less kind. The musicologist Robert Stove writes, “Sir Charles Villiers Stanford has not so much been neglected, but posterity has derived malicious satisfaction from ostentatiously yawing in his face.”

Centenary of Death

Villiers Stanford died 100 years ago, on 29 March 1924, and he untiringly campaigned for a national opera, as he saw “opera as a vital catalyst in Britain’s musical renaissance.” He was a mover and a shaker, but his music became associated with Victorian fustiness, worthy if ultimately inconsequential.

As Ralph Vaughan Williams wrote, “in Stanford’s music the sense of style, the sense of beauty, the feeling of a great tradition is never absent. His music is in the best sense of the word Victorian, that is to say, it is the musical counterpart of the art of Tennyson, Watts and Matthew Arnold.”

Critical Assessment

Charles Villiers Stanford as a boy

Villiers Stanford was a busy man. He composed roughly 200 works, including seven symphonies, about 40 choral works, nine operas, 11 concertos, and 28 chamber works. And this is in addition to songs, piano pieces, incidental music, and organ works. Stanford’s technical competence was never in doubt, as the composer Edgar Bainton wrote, “Whatever opinions might be held upon Stanford’s music, and they are many and various, it is always recognised that he was a master of means.”

It’s been suggested by countless critics that Stanford’s music lacked passion. In his operas, critics found music that ought to convey love and romance but fails to do so. His church music is “a thoroughly satisfying artistic experience, but one that is lacking in deeply felt religious impulse. And while Stanford had a real gift for melody often infused with the contours of Irish folk music, he never emulated comic operas but produced oratorios that “only occasionally matched worthiness with power and profundity.”

Beginnings

Charles Villiers Stanford

Born on 30 September 1852 in Dublin, Charles Villiers Stanford was the only child of the city’s most eminent lawyer. He grew up in a highly stimulating cultural and intellectual environment, and his childhood home was the meeting place of countless amateur and professional musicians. In fact, his father was a capable cellist and singer, and his mother an able pianist, with various celebrities such as Joseph Joachim visiting the home.

Stanford showed early musical promise, and he took violin, piano, and organ lessons. His teachers were of the highest calibre, including former students of Ignaz Moscheles. And he clearly had plenty of talent. He gave his first piano recital for an invited audience at the age of seven, presenting works by Beethoven, Handel, Mendelssohn, Moscheles, Mozart, and Bach. Long before the age of twelve, “he could play through all fifty-two Mazurkas by Chopin on sight,” and his earliest composition attempts emerged at the age of eight.

Cambridge and Leipzig

Charles Villiers Stanford’s parents

Not entirely unexpected, Stanford’s father wanted his son to enter the legal profession. Finally, in 1870, Stanford was able to gain the consent of his parents to pursue a career in music. He won an organ scholarship at Queens’ College, Cambridge, and immersed himself in various musical activities. He composed prodigiously and was elected assistant conductor to the Cambridge University Musical Society.

On the recommendation of Sir William Sterndale Bennett, Stanford spent the last six months of both 1874 and 1875 in Leipzig. He studied piano with Robert Papperitz and composition with Carl Reinecke. As Stanford reported, “Of all the dry musicians I have ever known, Reinecke was the most desiccated. He had not a good word for any contemporary composer, he loathed Wagner, sneered at Brahms, and had no enthusiasm of any sort.” To round off his continental study tour, Stanford spent some time in Berlin, working with Friedrich Kiel. “I learned more from him in three months,” he writes, “than from all the others in three years.”

Back in Cambridge

Stanford returned to Cambridge in January 1877, and he quickly became known as a conductor and composer. For one, he conducted the first British performance of Brahms’s First Symphony, and he completed his own First Symphony and the oratorio The Resurrection. He quickly followed up with his Second Symphony and the Piano Quintet, and as the organist at Trinity, he composed “some highly distinctive church music.”

At the age of 35, Stanford was appointed professor of music at Cambridge, with his students including Coleridge-Taylor, Holst, Vaughan Williams, and Ireland. By all accounts, he was not an easy teacher. He only taught in one-on-one tutorials, and “when students went into the teacher’s room, they came out badly damaged.” Apparently, Stanford’s teaching did not follow a prescribed plan or method. “His criticism,” as reported by a former student, “consisted for the most part of “I like it, my boy,” or “It’s damned ugly, my boy” (the latter in most cases).”

Royal College of Music

Stanford joined the staff of the newly inaugurated RCM as a professor of composition and conductor of the orchestra in 1883. He exerted considerable influence on a long list of students, and he instigated an opera class with an annual production. A scholar writes, “Stanford’s enthusiasm for opera is demonstrated by his lifelong commitment to a genre in which he enjoyed varying success.”

Stanford also took on the conductorship of the Bach Choir, the Leeds Philharmonic Society, and the Leeds Triennial Festival. He received honorary degrees from Oxford, Cambridge, Durham, and Leeds, and was knighted in 1902. Stanford continued to be active as a composer as well, but his music was gradually eclipsed by the young Edward Elgar. As Stanford was known as a hot-tempered and quarrelsome man, confrontations quickly ensued with Stanford writing, “Elgar, cut off from his contemporaries by his religion and his want of regular academic training, was lucky enough to enter the field and find the preliminary ploughing done.”

Thoughts on Music and Composers

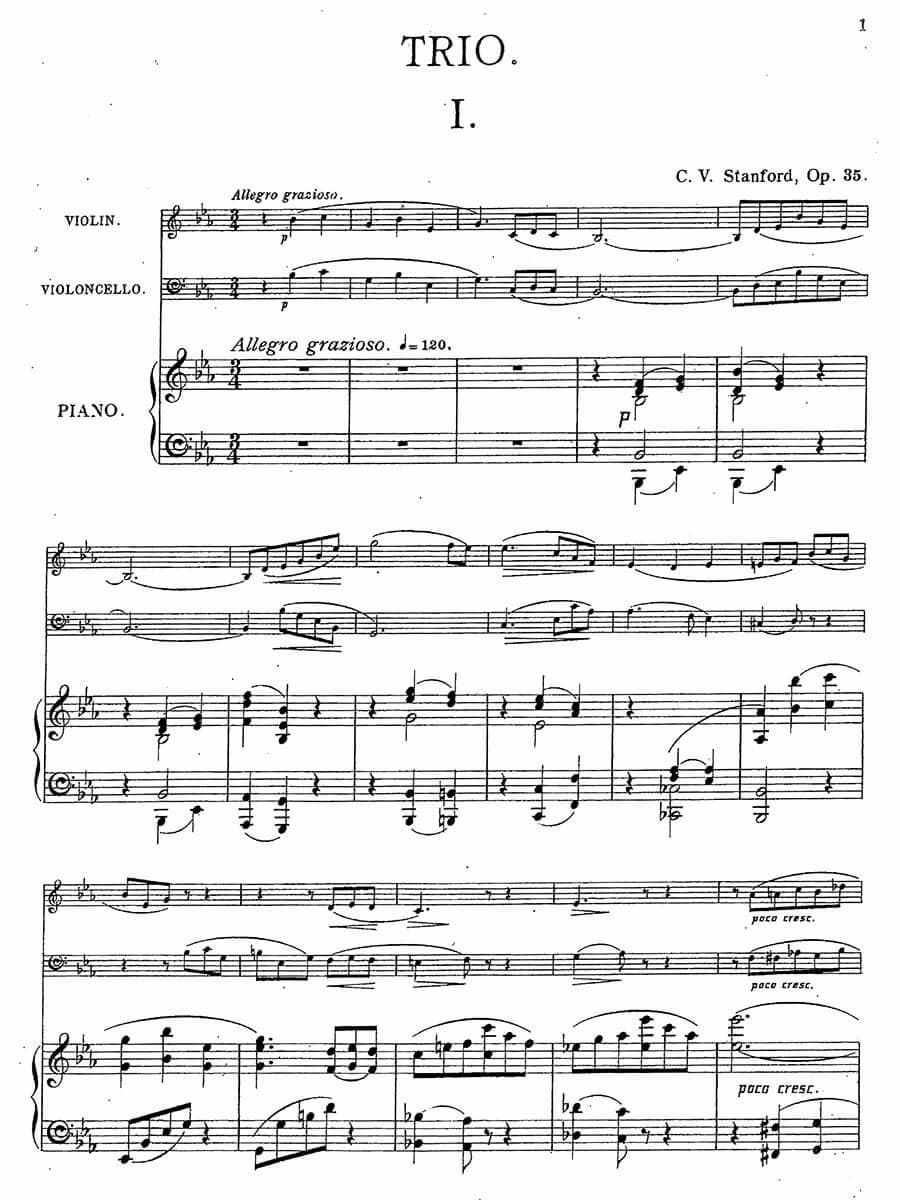

Charles Villiers Stanford’s Piano Trio

In his writings on music, Stanford frequently uses visual metaphors and references to painting and sculpture. His ideas on the subject can be reduced to simple statements. “A piece of music can survive bad texture and instrumentation, but never bad melody or design.” As he famously wrote, “Colour, the god of modern music, is in itself the inferior of rhythmic and melodic invention, although it will always remain one of its most important servants. Fine clothes will not make a bad figure good.”

In the musical culture war of the period, Stanford always sided with Brahms and against the modernists, although he had a great admiration for Wagner. He counted Berlioz and Liszt as lesser practitioners of the musical art, and he most bitterly objected to the music of Richard Strauss. Concerning Debussy and the new French School that emerged in the 1890’s, Stanford was deeply ambivalent.

Stanford was tormented by musical and aesthetic dichotomies at the end of his life. Always wrestling with his status in relation to Irish and English culture, he experienced what Yeats described as “my hatred tortures me with love, my love tortures me with hate.”

No comments:

Post a Comment