It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Friday, November 15, 2024

Bohemian Rhapsody for Symphony Orchestra and Solo Viola -

Piano Practice: Etudes for Intermediate Beginners

by Hermione Lai

Félix Le Couppey

I started piano lessons at the age of six, and it was a lot of fun. There were so many exciting things to explore, and thankfully I had a very nice and knowledgably teacher. At that age, I didn’t get bored with finger exercises and I just loved the first little piano pieces with cute and charming melodies. Many of these first etudes are custom-written for younger children—they certainly sound that way—which really doesn’t help beginning adult students. Nowadays there are countless piano methods on the market that promise to make the learning process easy and fun. At some point, however, you will still have to stumble across various etudes to strengthen your technique without numbing your brains. Finding etudes for your second or third years of piano studies that are both technically beneficial and musically entertaining isn’t an easy task. It was nevertheless a lot of fun finding interesting etudes composed for the intermediate-beginner pianist. Let’s get started with a graduated set of etudes by the French music teacher, pianist and composer Félix Le Couppey (1811-1887).

Félix Le Couppey: L’Alphabet, Op. 17

Félix Le Couppey was a student at the Paris Conservatoire, and by the tender age of 17 he was already employed at that institution as an assistant professor of harmony. He went on to receive the first prize in piano and harmony in 1825, and in piano accompaniment in 1828. Couppey became a full-time professor in 1837, and he taught piano at the Conservatoire from 1854 to 1886. He wrote a substantial number of textbooks on the piano, and an equally large number of studies and etudes. His most famous set is a series of elementary etudes called L’Alphabet. We find 25 etudes in total, and they do get progressively more difficult. These little charming didactic pieces offer an interesting approach to polyphony and harmony, and they are simply delightful.

Carl Czerny: Preliminary Studies to the

School of Velocity for piano, Op. 849

Any list of rudimentary etudes has to include the name Carl Czerny (1791-1857). So let’s get him out of the way. Czerny was greatly concerned about acquiring and maintaining piano technique, and he invested much time and energy in providing students with a graduated progress. He composed studies and etudes for all skill levels, and his Thirty New Studies in Technics, (Preliminary School of Velocity) Op. 849 bridges the gap between the Practical Method for Beginners, Op. 599 and The School of Velocity, Op. 299. Despite getting all the bad press, Czerny was a skilled pedagogue who tried to write pleasing compositions that combine musical potential and technical benefit.

Cornelius Gurlitt

The German composer Cornelius Gurlitt (1820-1901) counted Robert Schumann and Johannes Brahms among his close personal friends. Like Brahms, he hailed from Hamburg, and he studied at the Leipzig Conservatory with the famed Carl Reinecke for six years. He first appeared publically at the age of seventeen, and subsequently decided to go to Copenhagen to continue his studies. While taking organ, piano, and composition lessons, Gurlitt became friends with Niels Gade.

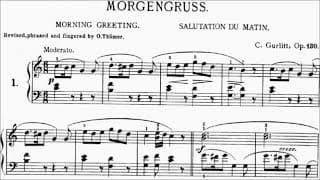

Cornelius Gurlitt: Morning Greeting, Op. 130 No. 1

Originally, Gurlitt took on a position as organist, and later moved to Leipzig where Gade was musical director of the Gewandhaus concerts. Always on the move, Gurlitt traveled to Rome and graduated as a Professor of Music in 1855. Returning to the Hamburg region, the Duke of Augustenberg engaged him as a teacher for three of his daughters. Gurlitt also worked as a military bandmaster, and then as an army conductor. He produced a vast number of compositions, including operas, songs, cantatas, and symphonies. But he is best known for his small and delightful piano works for students and amateurs. His 35 Easy Etudes, Op. 130 are charming musical miniature and portraits, prefaced by imaginative titles, that become gradually more challenging. Play

Béla Bartók

Béla Bartók composed a good many of my favorite pieces during my initial years of piano studies. Bartók traveled throughout remote regions of Eastern Europe and North Africa to record folk music. The songs and sounds he gathered became a fundamental element of his musical voice, and he was highly enthusiastic of passing on these cultural treasures to subsequent generations. His Mikrokosmos, a collection of 153 piano pieces in six books of graded difficulty is a work of great pedagogical value. But it is not a conventional piano method. According to Bartók, “technical and theoretical instructions have been omitted, in the belief that these are more appropriately left for the teacher to explain to the student.

Bartók: Mikrokosmos III

The first four volumes of Mikrokosmos were written to provide study material for the beginner pianist and are intended to cover, as far as possible, most of the simple technical problems likely to be encountered in the early stages. The material in volumes 1–3 has been designed to be sufficient in itself for the first, or the first and second, year of study.” The large-scale Mikrokosmos occupied him for several years. Bartók described the genesis of his new piano work in 1940: “Already in 1926, I was thinking of writing very easy piano music for the teaching of beginners. However, it was only in the summer of 1932 that I really began working on it, and at that time I composed about 40 pieces; in 1933-34, another 40 pieces, and an additional 20 in the following years. Finally, in 1938 I had 100-odd pieces together. But there were still some gaps. I filled in these last year, and among others, completed the first half of volume one.” These fantastic pieces are arranged in order of difficulty, so it is very easy to tailor assignments to the abilities of the student.

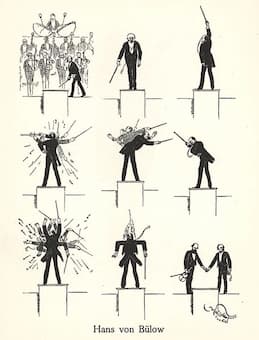

Hans von Bülow

Today, Hans von Bülow (1830-1894) is remembered as a highly influential conductor, and as the husband of Cosima née Liszt, who left him for Richard Wagner. What is frequently overlooked is his lasting influence as a pianist. During his American tour in 1876, a critic wrote, “Those who heard Hans von Bülow in recital, listened to piano playing that was at once learned and convincing. He was a deep thinker, analyzer; as he played one saw, as though reflected in a mirror, each note, phrase and dynamic mark of expression to be found in the work.” Bülow was one of the first performers to play the complete 32 piano sonatas by Beethoven, and contemporaries described him as the “greatest living authority on Beethoven.”

Hans von Bülow by Hans Schliessmann

In addition, Bülow premiered Liszt’s B-minor Sonata, and he also was one of the most successful pedagogues of the 19th century. He was employed in Frankfurt and Berlin and famous for his exacting master classes. Richard Strauss attended the Frankfurt classes and wrote, “I am rapidly coming to the conclusion that Bülow is not only our greatest piano teacher but also the greatest executant musician in the world.” Bülow’s legacy for today’s piano student is not expressed in original compositions, but in his precise editions. Aimed at players who might need technical and musical guidance, “Bülow’s editions offer very specific practical and artistic suggestions based on his own understanding of the works as teacher and performer.”

Jean-Baptise Duvernoy

Many of his editorial suggestions, such as pedal marks, dynamics, articulations, and musical commentaries are often explained at length in the prefaces and footnotes. Bülow favors long phrases, lyrical expression, and dramatic effects, which are achieved through fingering suggestions or by the addition or deletion of original slur marks and dynamics.” His prose footnotes explain how to execute certain passages in order to effectively bring out the appropriate expressions such as singing quality, humor, or drama—suggestions whose poetic and aphoristic style was also an important characteristic of his teaching.” And for the beginning student he edited a delightful collection of 25 Studies by the French pianist and composer Jean-Baptiste Duvernoy (1802-1880).

Christian Louis Köhler

The German pianist, composer, critic and teacher Christian Louis Köhler (1820-1886) was born in Brunswick and sent to Vienna to study music. He studied piano with the famed C.M. von Bocklet, and theory with the esteemed teachers Sechter and Seyfried. Köhler eventually settled in Königsberg, now Kaliningrad, and worked as a conductor in the local theatre. From 1847, Köhler devoted himself exclusively to piano pedagogy and to writing about music. He was music critic for the “Hartungsche Zeitung” and his correspondence articles from Königsberg for Brendel’s “Neue Zeitschrift für Musik” brought him to the attention of Liszt and Wagner in 1852. His first book, “The Melody of Language” established him as one of the leading German writers. In addition, Köhler remained influential throughout his career in the area of piano pedagogy. “He published collections of graded instructional pieces and books of exercises, published new editions of the works of Classical and Romantic composers, wrote widely disseminated books about piano pedagogy, and taught a great number of pupils. In all, he published over 300 original compositions, pedagogical works and editions, including 12 Easy Etudes, Op. 157.

Ludvig Schytte

The Danish composer, pianist and teacher Ludvig Schytte (1848-1909) originally trained as a pharmacist. He received his first musical training at the age of 22, and made such rapid progress that he was still able to embarked on a successful musical career abroad. He took lessons from Niels Gade in Leipzig, Wilhelm Taubert in Berlin, and from Franz Liszt in Weimar in 1884.

Ludvig Schytte: Easy Characteristic Etudes, Op.95

Schytte was appointed at various conservatories in Vienna, and by 1907 he had settled in Berlin as a teacher at the Stern Conservatory. He composed an imposing piano concerto, and his expansive piano sonata “bears witness to a more serious approach to the problems of musical form.” However, Schytte was also considered a master of miniature forms, and he is primarily remembered for about 200 attractive piano pieces, some of which became extremely popular. He composed numerous pedagogical piano methods, of which his collections of Etudes, especially, opp. 75, 95, 106, 161 and 174, are still in widespread use.

Henri Jérôme Bertini

Henri Jérôme Bertini (1798-1876) was born in London, but quickly returned to Paris with his parents. He received his early musical education from his father and his brother, a student of Muzio Clementi. There was no doubt that Bertini was a child prodigy, and his father took him on a concert tour of England, Holland, Flanders, and Germany. After studies in composition in England and Scotland he was appointed professor of music in Brussels but returned to Paris in 1821. Robert Schumann reviewed one of Bertini’s trios, and wrote, “Bertini writes easily flowing harmony but the movements are too long. With the best will in the world, we find it difficult to be angry with Bertini, yet he drives us to distraction with his perfumed Parisian phrases; all his music is as smooth as silk and satin.” We also know that Bertini gave a concert with Franz Liszt on 20 April 1828, playing Bertini’s transcription of Beethoven’s 7th symphony for piano eight hands. Bertini’s playing was described as “having Clementi’s evenness and clarity in rapid passages as well as the quality of sound, the manner of phrasing, and the ability to make the instrument sing characteristic of the school of Hummel and Moschelès.” And let’s not forget that Bertini was a celebrated teacher who concentrated on strict pedagogy. In all, he published 20 books of roughly 500 studies for all levels and abilities.

Giuseppe Concone

Giuseppe Concone (1801-1861) was one of the most influential singing instructors of his time. Originally born in Turin, he initially tried his hands at theatrical composition and produced an opera that failed to meet expectations. Discouraged he relocated to Paris to become a famous vocal and piano teacher. He published a good many books of vocal exercises that are still in use in vocal studios today. Specifically, he achieved worldwide recognition for a book of 50 solfeggi for a medium voice, 15 vocalizzi for soprano, 25 for mezzo-soprano, and a book of 25 solfeggi and 15 vocalizzi, 40 in all, for bass or baritone. “The contents of these books are melodious and pleasing, and calculated to promote flexibility of voice. The accompaniments are good, and there is an absence of the monotony so often found in works of the kind.” Concone returned to Turin after the French revolution of 1848, and he was appointed organist of the Royal Chapel. Besides publishing vocal primers, Concone also issued a collection of 15 Studies in Style and Expression for the piano. Sporting imaginative titles like “Anxiety,” “Melancholy,” “Robin Redbreast,” and “The Waves,” these etudes are especially appropriate for the early advanced pianist in developing appropriate expression and interpretation.

Collaborating With Samuel Dushkin: “Dear Sam”

The Polish-born American violinist Samuel Dushkin (1891-1976) is widely known for his extensive collaborations with Igor Stravinsky. The two men were compatible friends from the very beginning and eventually embarked on a concert tour through Europe and the United States, which lasted for the better part of five years. Dushkin was said to have had a gentle, self-effacing, and considerate character, which sharply contrasted with Stravinsky’s fiercely dynamic, egotistical and combative demeanour. A biographer writes, “much of the success of the friendship must be attributed to the violinist’s wholly unaggressive nature, as well as to his rich sense of humour.”

Samuel Dushkin

Stravinsky and Dushkin first met in Paris in 1931, but both had been in town for some time already. Dushkin had studied at the Paris Conservatoire, taking violin lessons with Guillaume Remy and attending composition classes with Ganaye. He made his Paris début in 1918 and subsequently toured widely, giving many important first performances. One such premiere performance took place on 19 October 1924 in Amsterdam, as Pierre Monteux conducted the Concertgebouw, and Dushkin was the soloist in the orchestrated version of Ravel’s Tzigane.

Bohuslav Martinů (1890-1959) had been living in Paris since 1923. In 1931, Dushkin premiered the Stravinsky Violin Concerto after having collaborated closely with the composer. The concerto was a resounding success, and Dushkin was very much the man of the hour. Dushkin was clearly on a roll, and he followed up by commissioning a violin concerto from Martinů in early 1932. The two men became good friends, and on the occasion of a visit, Charlotte Martinů fell ill with double pneumonia and a high fever. Dushkin took charge and had her admitted to the American Hospital at Neuilly, probably saving her life.

Bohuslav writes, “that violinist, Dushkin, is an American and has a lot of connections, so he found some help for us. There’s such an organisation among Americans that takes care of artists when they’re ill. They arranged for us to take Charlotte to the hospital, and they’re going to pay for the hospital care and the entire stay and treatment! Dushkin really devoted himself to her. He saw that I wouldn’t make it on my own.”

Bohuslav and Charlotte Martinů

The friendship between Martinů and Dushkin, however, did not make for a smooth collaboration on the violin concerto. Dushkin had been a creative and technical consultant throughout the gestation of the Stravinsky concerto. He offered advice and suggestions to Stravinsky, who had no experience as a string player. Martinů, on the other hand, had formerly been a professional violinist, and he did not need much assistance. Still, Dushkin suggested countless amendments to the solo part of the concerto, and Martinů tried to please his famous soloist. Nonetheless, as late as February 1934, he admitted in a letter to his family that Dushkin was still dissatisfied and that further work was needed.

Both men eventually lost interest in the concerto, and the score was presumed lost. A Martinů biographer wrote in 1962, “from the beginning of the thirties dates an unfinished Violin Concerto for the American virtuoso Samuel Dushkin. I recall the frequent exchange of opinions between the two artists regarding various details in the concerto, which is apparently the reason for the composer not finishing it and the manuscript of which mysteriously disappeared.” However, the complete manuscript did, in fact, exist, and it did not disappear.

The concerto manuscript was not rediscovered until 1968, nine years after the composer’s death. It had probably been sent by Martinů to Boaz Piller, a bassoonist with the Boston Symphony Orchestra and a close personal friend of Martinů, Stravinsky, Bloch, and Casals, in 1937. Martinů had probably been looking to arouse the interest of conductor Serge Koussevitzky, but in the event, the manuscript was deposited by Piller into the archives of the musicologist Hans Moldenhauer in 1961.

Over the course of forty years, Moldenhauer had assembled an unparalleled collection of primary sources documenting the artistic thoughts and compositional process of celebrated and lesser-known figures of western music dating from the Middle Ages through the twentieth century. This collection, now housed at Northwestern University, was consulted by musicologist Harry Halbreich in 1968 during his work on a catalogue of Martinů’s works. Finally rediscovered, the concerto was first performed in Chicago on 25 October 1973 under George Solti, with Josef Suk as the soloist. It was not a rousing success, as a critic wrote, “it isn’t hard to deduce why the composer never promoted performance or publication of this opus during his lifetime.”

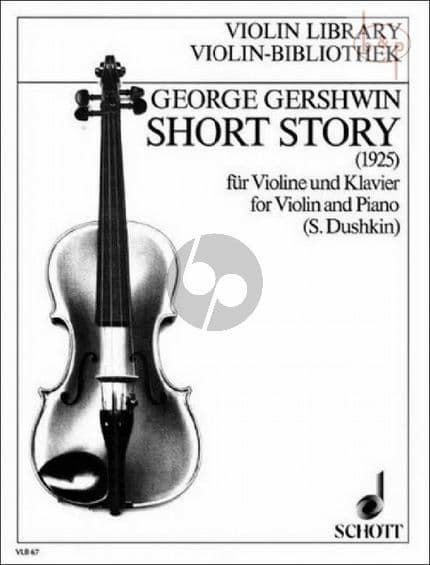

Gershwin’s Short Story

1924 was a hugely successful year for George Gershwin (1898-1937). The premiere of his Rhapsody in Blue had brought down the house, and the musical Lady Be Good! received a wonderfully successful launch. Dushkin was a close personal friend, and he decided to request a recital piece from Gershwin in late 1924. Gershwin was enthusiastic, and the two young men decided to collaborate.

Gershwin was still learning the craft of orchestration and was eager to explore the palette of colours available on instruments other than keyboards. In no time, Gershwin and Dushkin put together Short Story, taking as a starting point two short piano pieces that Gershwin had written a couple of years earlier but had not yet been published. The first piece features a languid and bluesy melody, while the second, more light-hearted syncopated tune, takes on the style of a ragtime. Dushkin and Gershwin premiered Short Story in 1925, and Dushkin programmed it often and recorded it in 1928.

William Schuman

In 1946, Samuel Dushkin approached William Schuman (1910-1992) for a violin concerto he hoped he would be able to premiere with Koussevitzky and the BSO. Once Schuman had completed the score, he sent it to Koussevitzky for review in late 1947. Unfortunately, Dushkin’s playing had significantly deteriorated over the years, and Koussevitzky told Schuman, “I will play it, but not with Dushkin. You must tell Dushkin.” This put Schuman in a rather tricky situation because Dushkin had already paid for the concerto and had exclusive rights to it for three years. Koussevitzky was not interested in legal niceties and said, “I don’t care what your agreement is. Take it away from him. We’ll give it to Isaac Stern and play it with the Boston Symphony.”

Schuman broke the news to Dushkin in a hotel bar, telling him that he could not go on with the Violin Concerto. “I know you were a great performer at one time, but no one is going to play it with you.” Apparently, Dushkin erupted in white-hot anger, snapping the stem of his martini glass in two.

William Schuman’s Violin Concerto

Schuman waited for three years, as Dushkin insisted on maintaining his exclusive right to the work. Finally the concerto was scheduled for performance on 10 February 1950 with Isaac Stern as the soloist and conductor Charles Munch. While the conductor loved the work, the composer accused Stern of not having grasped the intellectual underpinnings of the work and, therefore, of not presenting the concerto in its best light.

Schuman writes, “the inability of certain performers who are only conventional literature performers to come to grips with a new piece on its own terms, so Stern never understood it except superficially. He always thought the opening, which he used to sing, was frenetic, even though I want that to be broadly romantic…he would never play it that way.” Dushkin and Schuman did stay friends, and Schuman wrote at the premiere of the concerto’s final version in 1959, “I thought about you during the period of preparation and performance of the Concerto in Aspen. I cannot help but feel that somehow you would have been pleased.”

During his extensive performance career, Dushkin published many arrangements and transcriptions for violin and piano. They are published as the “Samuel Dushkin Repertoire,” and include arrangements of music by Bizet, Rachmaninoff, Albéniz and Wieniawski, and Reger. The Dushkin Repertoire also includes a compilation of arrangements by relatively unknown composers, including C. Artok, R. Felber, A. Sasonoff, and Paul Kirman. The Dushkin arrangements were eagerly taken up by a host of eminent violinists, and they are still part of today’s recital repertoire.

Henry Cowell - a musical life

Daniel Reuss on Frank Martin (60 seconds)

Sigurd Raschèr: King of Sax

By Georg Predota, Interlude

Sigurd Raschèr

Hector Berlioz wrote, “I find the main advantage of the saxophone to be the wide variety and beauty of its expressive possibilities. Sometimes low and calm; then passionate, dreaming, and melancholy; at times as gentle as the breath of an echo; other times like the vague, lamenting wail of wind in the trees.” The instrument was used in French opera for special effects and to add orchestral colour. It eventually became an essential member of jazz ensembles and swing bands. However, there is plenty of concert music in the classical idiom for the saxophone, and most of it was inspired and composed for Sigurd Raschèr (1907-2001).

Adolphe Sax, 1850s

Sigurd Raschèr was born in Germany to an American military physician. Initially, he studied the clarinet, but in order to become part of a dance band, he started to play the saxophone. “As I did this for a couple of years,” he writes, “I became more and more unsatisfied. I started to practice furiously and slowly found out that it had more possibilities than was usually thought.” After moving to Berlin, he met the composer Edmund von Borck, who composed a concerto for him in 1932. The work was first performed at the General German Composers Festival in Hanover and was considered a huge success. In fact, the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra picked up the piece for a performance, and this was followed by performances in Strasbourg and in Amsterdam. Raschèr was lauded for his brilliant agility, sweetness of tone and musical sensibility and for substantially extending the range of the saxophone by more than an octave.

Contemporary reviewers wrote, “Raschèr’s mastery of his instrument and the control of an almost inaudible pianissimo is phenomenal. His cantabile has real beauty, and his dexterity must be almost unequalled.” Paul Hindemith (1895-1963) had been interested in the sound of the saxophone in the 1920s, and he included the instrument in the scores for his theatre works. It features prominently in his opera Cardillac, the story of a goldsmith who is uncontrollably in love with the jewellery he creates and ends up murdering the people who purchase them. In that score, the tenor saxophone, with its “vaguely erotic connotations of timbre, represents the goldsmith’s secret passion.” Raschèr approached Hindemith for a dedicated composition, and Hindemith responded with his Concert Piece for Two Alto Saxophones in 1933. Hindemith told his publisher that he had “written very quickly, a gymnastic exercise, an extensive saxophone duet.” As Raschèr had secured an appointment to teach at the Royal Danish Conservatory in Copenhagen, he took the Hindemith manuscript with him. Raschèr and his daughter Carina premiered the piece only in 1960.

A Yamaha saxophone

Raschèr’s engagement in Denmark was quickly complemented by an appointment in Malmö, Sweden. He continued to tour extensively, performing concerts in Norway, Italy, Spain, Poland, Hungary, and England. While concertising in England, Raschèr met Eric Coates (1886-1957), a leading violist, conductor and popular composer of light music. During his early career, Coates was primarily influenced by the music of Arthur Sullivan, but eventually, his musical style evolved “in step with changes in musical taste.” Coates primarily composed orchestral music and songs, and he never really wrote for the theatre and only occasionally for the cinema. In his Saxo-Rhapsody for Raschèr, however, he incorporated countless elements derived from jazz and dance-band music.

Jacques Ibert

In April 1936, Raschèr participated in the 14th Festival of the International Society for Contemporary Music (ISCM), and he premiered the Concertino da Camera by Jacques Ibert (1890-1962). Ibert was of the opinion that high-quality classical music does not always have to be deadly serious. He summed up his general approach and attitude towards music in a few words. “I want to be free and independent of the prejudices which arbitrarily divide the defenders of a certain tradition and the partisans of a certain avant-garde.” As such, Ibert rejected the two artistic trends that dominated the French musical scene at this time: French Impressionism and German Expressionism. Ibert only wrote music that he was happy to listen to himself. His Concertina da Camera is scored for alto saxophone and 11 instruments. The composer takes advantage of a number of contemporary musical trends, including the prevailing jazz and blues influences of his day.

Frank Martin

The Swiss composer Frank Martin (1890-1974) initially followed the wishes of his parents and studied mathematics and physics. Concordantly, he took private music lessons with Joseph Lauber but never studied at a conservatory. Nevertheless, his music shows a clear awareness of the various strands of contemporary music. We find serialism, extended tonality, free atonality, neo-classicism and rhythmic experimentations. Martin is indebted to both French and German musical styles, and his Saxophone Ballade, dating from 1938, sounds “chromatic melodies, jabbing rhythms and a predilection for sections in a playful and often syncopated compound time, but with a high level of dissonance to excite the ear.”

Raschèr made his American début in 1939, and he played with the Boston SO and the New York PO, “the first saxophonist to appear as a soloist in a subscription concert given by either orchestra.” He would subsequently perform with more than 250 orchestras worldwide. A historian writes, “Throughout the middle decades of the twentieth century, a preponderance of the significant new saxophone solo and chamber repertoire would appear with the familiar dedication to Sigurd M. Raschèr, the outcome of not just his ongoing commitment to motivating some of the world’s finest composers, but also in part the result of genuine close friendships he developed with so many… And it is not without significance that among all the pieces written for and dedicated to him during his life, not one was commissioned. He inspired new music, he never needed to purchase it.” Case in point, the American composer and educator Maurice Whitney (1909-1984) was Raschèr’s personal friend, and the Intro and Samba was freely composed and dedicated to him in 1951.

In 1951 Sigurd Raschèr approached William Grant Still (1895-1978) for a saxophone commission. He writes, “I know many of your works, as every educated musician does. And many times, I did think: Still would be a composer who could write something for the Saxophone that would be truly in the nature and style of the instrument… I am convinced that composition from your hand would meet with very considerable interest, wherever performed.” Still completed the commission in 1954, and “because of its apparent simplicity and absence of technical virtuosity,” his Romance was initially overlooked by many recitalists. In the manner of Franz Schubert, Still introduces several phrases that are restated a number of times. “The challenge for the interpreter is to reveal fresh layers of meaning with each repetition, thus providing the listener with ample opportunity to experience the subtle tonal shadings and contrasts available from the saxophone.” The orchestra setting, in turn, reflects Still’s experience of working as a composer for many Hollywood films and as a creator of television scores.

Henry Cowell

Raschèr stirred up a good bit of controversy by advocating that the saxophone used in classical music should sound like the inventor Adolphe Sax had intended. Sax specified that the interior of the mouthpiece should be large and round. With the advent of big-band jazz, however, saxophonists began to experiment with different shapes to “get a louder and edgier sound.” As a result, narrow-chamber mouthpieces also became common use by classical saxophonists. Raschèr was emphatic that the sound produced by modern mouthpieces provided the jazz player with a loud, penetrating sound but that “this particular sound was not appropriate for use in classical music.” Because the narrow-chamber mouthpiece became universally popular, Raschèr engaged a manufacturer to make official “Sigurd Raschèr brand” mouthpieces; they are still produced today.

Sigurd Raschèr with Carl Anton Wirth

The Idlewood Concerto by Carl Anton Wirth (1912-1986) was first performed on 22 October 1956 by the Chattanooga Symphony Orchestra. A critic wrote, “The overall impression of this work is of peaceful repose and meditation. The emphasis is less on rigid tonality and rhythm than on melody. The concerto develops from a melodic seed and proceeds without redundancy and complex variations. It is fresh and of lean construction. There is nothing superfluous in the progression and development of ideas.” Raschèr taught at the Juilliard School, the Manhattan School, and the Eastman School of Music. In 1969, he founded the Raschèr Saxophone Quartet, which commissioned and recorded many works by composers such as Berio, Glass, and Xenakis. In all, 208 works for saxophone are dedicated to him, and we should rightfully consider him the “King of Sax.”

György Cziffra: Transcriptions and Paraphrases

by Georg Predota, Interlude

Childhood

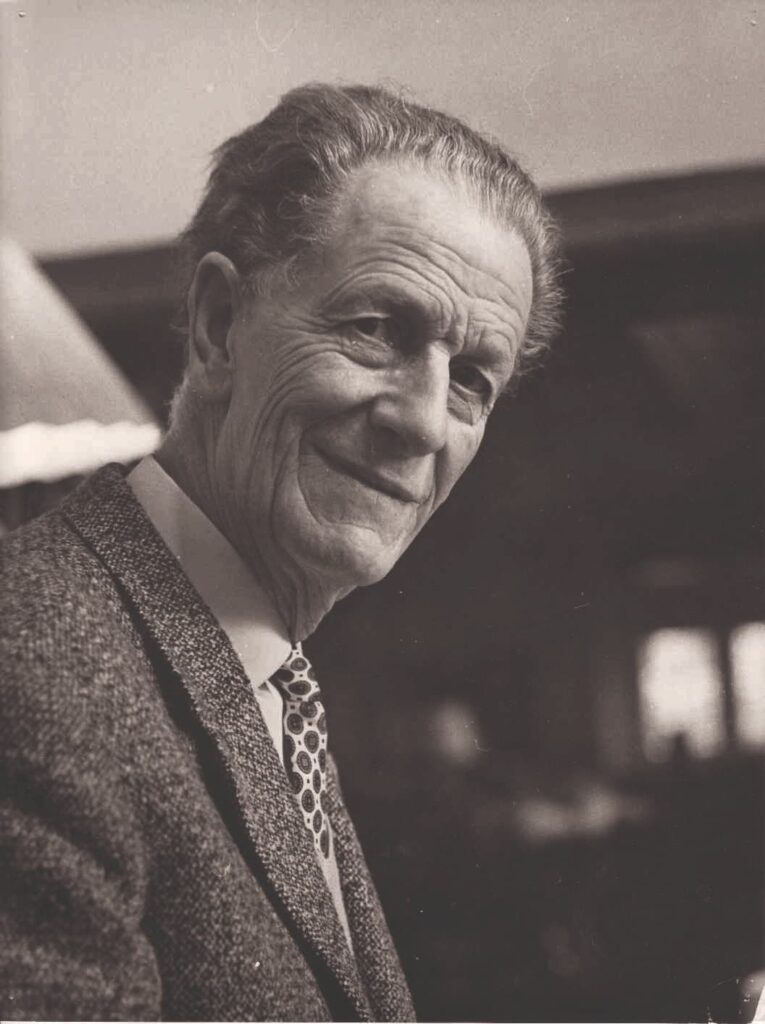

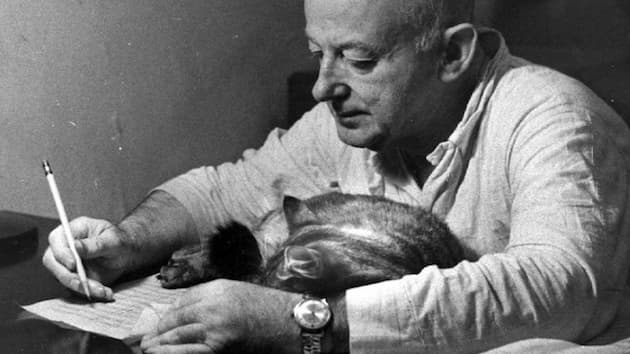

György Cziffra

Much has been written about his growing up in dire poverty on the outskirts of Budapest and his incredible musical talent on display at an early age. To be sure, the origins of his improvisational art can be traced back to his childhood and his ability to learn music without scores. Essentially, he mimicked the piano playing of his sister and repeated and improvised over tunes sung by his parents. “Thanks to the Strausses, the Offenbachs, and many others,” he later writes, “by the time I was five years old, improvisation at the piano became basically my only daily practice. It was more than mere pleasure; I had the power in my hands, and whenever I liked, I could break away from reality.”

Bar Pianist

Forced to contribute to the meagre household income of his family, Cziffra initially earned money as a child improvising on popular music at a local circus. In the 1930s, and during his studies at the Franz Liszt Academy, however, Cziffra decided to earn money by performing as a bar musician. As he later wrote, “I met some bar musicians, and they gave me some good advice as to how to enter the realm of popular music. Later, they invited me to listen to them play, and slowly, I transformed into a pop musician and, for a while, this was my real profession.” While it was still his ambition to become a concert pianist, Cziffra enjoyed improvising and started to fashion a number of transcriptions of popular American songs and film scores.

Process of Improvisation

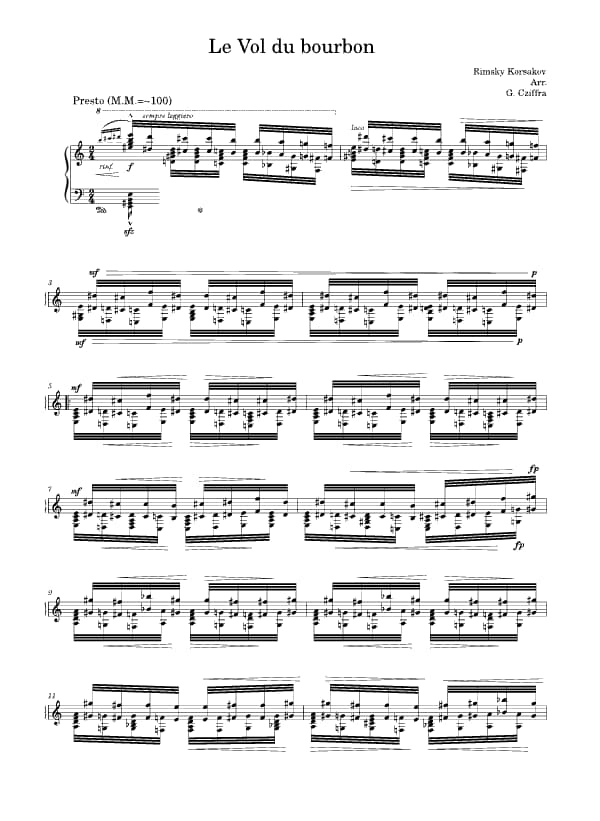

György Cziffra’s ‘Flight of the Bumblebee’ Transcription

He greatly enjoyed working in bars and taverns, and everybody knew him for his marvellous improvisations, which went from jazz, the fandango, and the czardas to the pasodoble. As he wrote, “I ended up dividing the nights between several lucrative places, spending two hours or so at each.” Between 1947 and 1950, Cziffra went on European tours with a jazz band, and in his autobiography, he described the process of improvisation.

“While I give myself over completely to the moment of inspiration, while I give the field of form and theme over completely to my imagination, I always try to maintain a discipline of my thoughts on the following two-three measures so that my hands can follow the path of my vision. The practice of this, at one-time tender and at another time enchanting, made it possible for me to discover the future form of piano performance in the moments of creation.”

First Performances

He quickly became recognized as a superb jazz pianist and virtuoso, and his performances soon became legendary. And in the footsteps of his hero Franz Liszt, Cziffra improvised dazzling fantasies on opera themes. From his earliest concert appearances, Cziffra wanted to finish a recital with “a short piece, that personally, could stand alone, and which was not prepared for eternity. When I improvise, I feel as if I become one with myself, and my body is freed from all earthly pain. It is truly a process of going beyond my talents, which makes it possible on each occasion to step over the known boundaries of the technical side of the piano performance.”

His career was on the verge of collapsing as Cziffra was imprisoned and subject to hard labour after attempting to flee Hungary in 1950. He was tasked with transporting blocks of stone and needed four months of physiotherapy after leaving prison in order for his fingers, swollen by work of a very different nature, to grow used to the piano again gradually. Cziffra’s first concerts after his release from prison were, to quote the pianist, “so dull as to verge on the incompetent. Fortunately, the transcriptions and improvisations I played as encores at the end of each recital compensated for the rest and shook my audience out of their apathy. These intense moments were like the ecstasy of love. One critic went so far as to say that this was the mastery not of a pianist but of the pianist of one’s dream.”

Success in the West

György Cziffra

When Cziffra made his Paris debut in 1956, he was hailed as “the most extraordinary pianistic phenomenon since Horowitz… Probably the only one of his Generation who can give each note a different colouration without ruining the continuity of the work he is performing.” One performance review even carried the headline, “Franz Liszt has arisen from the dead in a demonic experience, eliciting the landscape and soul of Hungary like a vision in drama and transfiguration.” However, not everybody was enthralled. His recitals featuring his own brilliant paraphrases were considered “brilliantly vulgar confections.” Cziffra himself said about his playing, “I became the profession’s Antichrist due to my improvisations, which multiplied the difficulties ten times over.”

Virtuosity

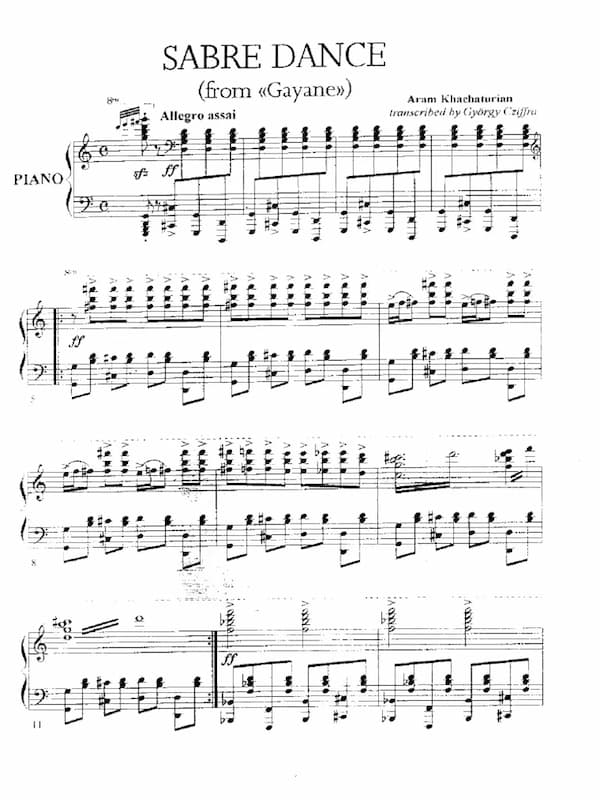

It was readily assumed that Cziffra’s transcriptions were simply composed for the sake of virtuosity. However, as has been pointed out, the most dazzling passages were born from the composer’s extreme intensity of expression, and the fiery passages were motivated by inner musical force. Cziffra believed that technical mastery should never be displayed for its own sake but rather made subservient to a powerful emotional intellect and a cultured mind. He never accepted praise for his phenomenal technique and sharply reproached admirers, “I don’t care about technique. What you call technique is simply an expression of feeling.”

Franz Liszt

György Cziffra’s ‘Sabre Dance’ Transcription

During a radio interview in 1984, Cziffra spoke about his close spiritual and artistic connection to Franz Liszt. “I started piano similarly to Liszt at a very early age, and I was making people happy with my improvisations, just like him. And, well, I think that I wasn’t too much below his capabilities in this field. This is not the question of immodesty or modesty; this I know because I was able to improvise in such a way those days that I could think four measures ahead. And I realise that very few people are able to do this. This is similar to a chess game, where one player is playing with twelve others simultaneously. By the time my hands arrive somewhere, my brain has already gone further.”

“And this is perhaps the most difficult thing about it. This is why when I make sound recordings improvising on certain melodies, numerous wrong notes happen, and mistakes; my hands cannot follow the outrageous speed that my brain commands. And at the same time, I shape the form of the piece as well. I am not only interpreting, but I am creating the actual piece at the moment. So, I think I am also a creator from another respect, certainly not to such extent as Franz Liszt was, but some congenial trait we do share.”

Notating Improvisations

Improvising is one thing; committing these flights of fancy and inspiration to paper is another. As Cziffra explained, “to put on paper the uniqueness of the improvisational form is extremely difficult… One needs an ear and untiring patience to put these improvisational sessions on paper.” A good many pianists have tried, and even more have failed and left the task unfinished. “But then my son George said that he would like to give it a try. With a tremendous amount of energy and enthusiasm, he took on the work.”

“Slowing down the tape in both directions, George wrote down the place of each sound, and slowly, after a point, he was able to give form to a certain amount of my musical creations. Finally, I too became involved in writing down the musical notes, which now turned into true compositions, which mirrored my thoughts and emotions.” Cziffra was certainly hoping that the pages of his published transcriptions would open the door to new possibilities and encourage a less stereotypical and more personal approach to performances of classical piano music.

Historical Legacy

Monument of György Cziffra in Budapest

Cziffra’s transcriptions and paraphrases left a dazzling record of his seemingly superhuman power. However, at the height of his popularity in the 50s and 60s, he seemingly vanished due to personal tragedy and changing tastes and fashion. He was frequently accused of using composers as a springboard for personal excess and idiosyncrasy, and audiences became weary of Romantic exaggeration and “turned elsewhere in search of greater depth and spiritual refreshment.”

His public image has always been highlighted by the recognition of his prodigious pianistic abilities and achievements. Yet, his critics always saw him as little more than a technician or notable interpreter of Liszt. Indifference to his unique powers has become almost commonplace, and in some quarters, he was even vilified. A French reviewer wrote, “when one plays like this, the best thing to do is to commit suicide.”

Critical Assessment

To be sure, Cziffra could play with pure elegance and simple, direct expression, but he inevitably polarised critical opinion and aroused stormy controversy. A critic wrote, “Cziffra could never play louder without getting faster,” and this particular shortcoming was attributed to haphazard and ill-disciplined technique. As you might well imagine, Cziffra wasn’t particularly enamoured with critics either, calling them “carrion beetles of the mind… easily recognized by their boundless pride and pathetic intellect.” To be sure, Cziffra’s ample use of rubato and variable tempi did not agree with current concert practice “but were the mark of artistic freedom and individuality of earlier times.”

The French-Cypriot pianist Cyprien Katsaris explained in a 2012 interview, “Cziffra had that terrible label as a circus-virtuoso pianist and very few people were willing to speak openly about all the good things about him. I think this is absolutely insane… He used his incredible virtuosity in an expressive way – whether it was revolt, whether it was anger, tenderness, or serenity. He was able to do so much with the wide range of whatever he played.” Cziffra was much more than a mere virtuoso, and his lyricism was sublime and his “personal commitment and distinctive musicianship reveal themselves in a number of fine recordings of keyboard music by C.P.E. Bach, Domenico Scarlatti, François Couperin, Johann Tobias Krebs, Jean-Philippe Rameau, Jean-Baptiste Lully, Mozart, and Clementi.”

His performances were always characterised by an unconditional spontaneity and the impulsiveness of the moment, and many critics denied him the ability “to interpret works that are less virtuosic in a coherent and true-to-the-text manner.” For Cziffra, “the interpreter’s role in society is like a keepers’ watching over people’s emotions to prevent them from being worn away by a soul-destroying everyday existence…Finally, my virtuosity no longer prevented people from seeing the wood for the trees.”