by Georg Predota, Interlude

Childhood

György Cziffra

Much has been written about his growing up in dire poverty on the outskirts of Budapest and his incredible musical talent on display at an early age. To be sure, the origins of his improvisational art can be traced back to his childhood and his ability to learn music without scores. Essentially, he mimicked the piano playing of his sister and repeated and improvised over tunes sung by his parents. “Thanks to the Strausses, the Offenbachs, and many others,” he later writes, “by the time I was five years old, improvisation at the piano became basically my only daily practice. It was more than mere pleasure; I had the power in my hands, and whenever I liked, I could break away from reality.”

Bar Pianist

Forced to contribute to the meagre household income of his family, Cziffra initially earned money as a child improvising on popular music at a local circus. In the 1930s, and during his studies at the Franz Liszt Academy, however, Cziffra decided to earn money by performing as a bar musician. As he later wrote, “I met some bar musicians, and they gave me some good advice as to how to enter the realm of popular music. Later, they invited me to listen to them play, and slowly, I transformed into a pop musician and, for a while, this was my real profession.” While it was still his ambition to become a concert pianist, Cziffra enjoyed improvising and started to fashion a number of transcriptions of popular American songs and film scores.

Process of Improvisation

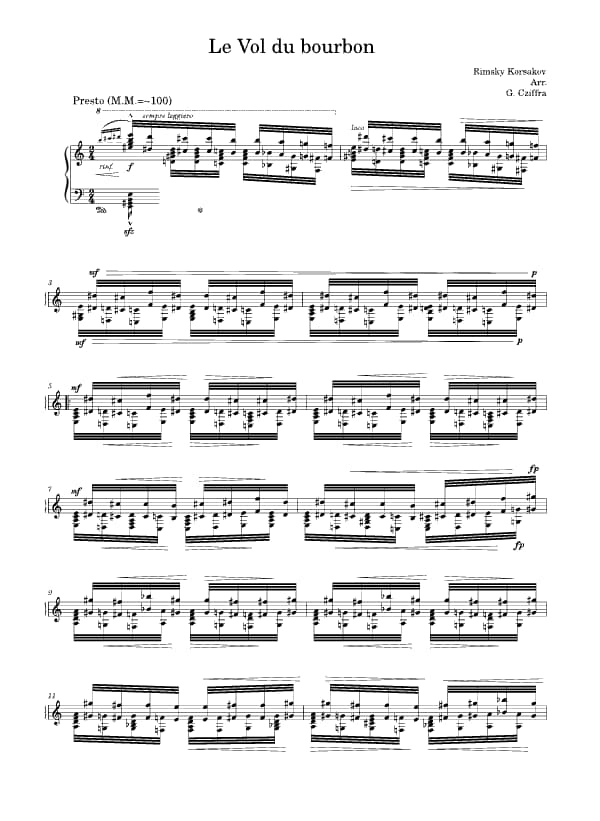

György Cziffra’s ‘Flight of the Bumblebee’ Transcription

He greatly enjoyed working in bars and taverns, and everybody knew him for his marvellous improvisations, which went from jazz, the fandango, and the czardas to the pasodoble. As he wrote, “I ended up dividing the nights between several lucrative places, spending two hours or so at each.” Between 1947 and 1950, Cziffra went on European tours with a jazz band, and in his autobiography, he described the process of improvisation.

“While I give myself over completely to the moment of inspiration, while I give the field of form and theme over completely to my imagination, I always try to maintain a discipline of my thoughts on the following two-three measures so that my hands can follow the path of my vision. The practice of this, at one-time tender and at another time enchanting, made it possible for me to discover the future form of piano performance in the moments of creation.”

First Performances

He quickly became recognized as a superb jazz pianist and virtuoso, and his performances soon became legendary. And in the footsteps of his hero Franz Liszt, Cziffra improvised dazzling fantasies on opera themes. From his earliest concert appearances, Cziffra wanted to finish a recital with “a short piece, that personally, could stand alone, and which was not prepared for eternity. When I improvise, I feel as if I become one with myself, and my body is freed from all earthly pain. It is truly a process of going beyond my talents, which makes it possible on each occasion to step over the known boundaries of the technical side of the piano performance.”

His career was on the verge of collapsing as Cziffra was imprisoned and subject to hard labour after attempting to flee Hungary in 1950. He was tasked with transporting blocks of stone and needed four months of physiotherapy after leaving prison in order for his fingers, swollen by work of a very different nature, to grow used to the piano again gradually. Cziffra’s first concerts after his release from prison were, to quote the pianist, “so dull as to verge on the incompetent. Fortunately, the transcriptions and improvisations I played as encores at the end of each recital compensated for the rest and shook my audience out of their apathy. These intense moments were like the ecstasy of love. One critic went so far as to say that this was the mastery not of a pianist but of the pianist of one’s dream.”

Success in the West

György Cziffra

When Cziffra made his Paris debut in 1956, he was hailed as “the most extraordinary pianistic phenomenon since Horowitz… Probably the only one of his Generation who can give each note a different colouration without ruining the continuity of the work he is performing.” One performance review even carried the headline, “Franz Liszt has arisen from the dead in a demonic experience, eliciting the landscape and soul of Hungary like a vision in drama and transfiguration.” However, not everybody was enthralled. His recitals featuring his own brilliant paraphrases were considered “brilliantly vulgar confections.” Cziffra himself said about his playing, “I became the profession’s Antichrist due to my improvisations, which multiplied the difficulties ten times over.”

Virtuosity

It was readily assumed that Cziffra’s transcriptions were simply composed for the sake of virtuosity. However, as has been pointed out, the most dazzling passages were born from the composer’s extreme intensity of expression, and the fiery passages were motivated by inner musical force. Cziffra believed that technical mastery should never be displayed for its own sake but rather made subservient to a powerful emotional intellect and a cultured mind. He never accepted praise for his phenomenal technique and sharply reproached admirers, “I don’t care about technique. What you call technique is simply an expression of feeling.”

Franz Liszt

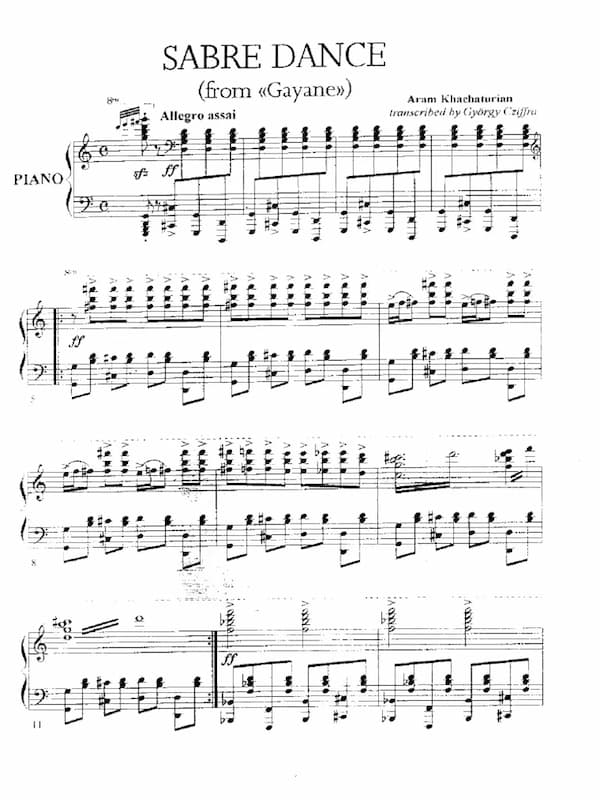

György Cziffra’s ‘Sabre Dance’ Transcription

During a radio interview in 1984, Cziffra spoke about his close spiritual and artistic connection to Franz Liszt. “I started piano similarly to Liszt at a very early age, and I was making people happy with my improvisations, just like him. And, well, I think that I wasn’t too much below his capabilities in this field. This is not the question of immodesty or modesty; this I know because I was able to improvise in such a way those days that I could think four measures ahead. And I realise that very few people are able to do this. This is similar to a chess game, where one player is playing with twelve others simultaneously. By the time my hands arrive somewhere, my brain has already gone further.”

“And this is perhaps the most difficult thing about it. This is why when I make sound recordings improvising on certain melodies, numerous wrong notes happen, and mistakes; my hands cannot follow the outrageous speed that my brain commands. And at the same time, I shape the form of the piece as well. I am not only interpreting, but I am creating the actual piece at the moment. So, I think I am also a creator from another respect, certainly not to such extent as Franz Liszt was, but some congenial trait we do share.”

Notating Improvisations

Improvising is one thing; committing these flights of fancy and inspiration to paper is another. As Cziffra explained, “to put on paper the uniqueness of the improvisational form is extremely difficult… One needs an ear and untiring patience to put these improvisational sessions on paper.” A good many pianists have tried, and even more have failed and left the task unfinished. “But then my son George said that he would like to give it a try. With a tremendous amount of energy and enthusiasm, he took on the work.”

“Slowing down the tape in both directions, George wrote down the place of each sound, and slowly, after a point, he was able to give form to a certain amount of my musical creations. Finally, I too became involved in writing down the musical notes, which now turned into true compositions, which mirrored my thoughts and emotions.” Cziffra was certainly hoping that the pages of his published transcriptions would open the door to new possibilities and encourage a less stereotypical and more personal approach to performances of classical piano music.

Historical Legacy

Monument of György Cziffra in Budapest

Cziffra’s transcriptions and paraphrases left a dazzling record of his seemingly superhuman power. However, at the height of his popularity in the 50s and 60s, he seemingly vanished due to personal tragedy and changing tastes and fashion. He was frequently accused of using composers as a springboard for personal excess and idiosyncrasy, and audiences became weary of Romantic exaggeration and “turned elsewhere in search of greater depth and spiritual refreshment.”

His public image has always been highlighted by the recognition of his prodigious pianistic abilities and achievements. Yet, his critics always saw him as little more than a technician or notable interpreter of Liszt. Indifference to his unique powers has become almost commonplace, and in some quarters, he was even vilified. A French reviewer wrote, “when one plays like this, the best thing to do is to commit suicide.”

Critical Assessment

To be sure, Cziffra could play with pure elegance and simple, direct expression, but he inevitably polarised critical opinion and aroused stormy controversy. A critic wrote, “Cziffra could never play louder without getting faster,” and this particular shortcoming was attributed to haphazard and ill-disciplined technique. As you might well imagine, Cziffra wasn’t particularly enamoured with critics either, calling them “carrion beetles of the mind… easily recognized by their boundless pride and pathetic intellect.” To be sure, Cziffra’s ample use of rubato and variable tempi did not agree with current concert practice “but were the mark of artistic freedom and individuality of earlier times.”

The French-Cypriot pianist Cyprien Katsaris explained in a 2012 interview, “Cziffra had that terrible label as a circus-virtuoso pianist and very few people were willing to speak openly about all the good things about him. I think this is absolutely insane… He used his incredible virtuosity in an expressive way – whether it was revolt, whether it was anger, tenderness, or serenity. He was able to do so much with the wide range of whatever he played.” Cziffra was much more than a mere virtuoso, and his lyricism was sublime and his “personal commitment and distinctive musicianship reveal themselves in a number of fine recordings of keyboard music by C.P.E. Bach, Domenico Scarlatti, François Couperin, Johann Tobias Krebs, Jean-Philippe Rameau, Jean-Baptiste Lully, Mozart, and Clementi.”

His performances were always characterised by an unconditional spontaneity and the impulsiveness of the moment, and many critics denied him the ability “to interpret works that are less virtuosic in a coherent and true-to-the-text manner.” For Cziffra, “the interpreter’s role in society is like a keepers’ watching over people’s emotions to prevent them from being worn away by a soul-destroying everyday existence…Finally, my virtuosity no longer prevented people from seeing the wood for the trees.”

No comments:

Post a Comment