by

Joseph Haydn has entered music history as a jovial, grandfatherly figure with a reputation for a quick wit. Generations later, we still chuckle at the stories behind the Surprise Symphony or the Farewell Symphony. His famous good humor is all the more striking considering his often difficult upbringing.

Joseph Haydn has entered music history as a jovial, grandfatherly figure with a reputation for a quick wit. Generations later, we still chuckle at the stories behind the Surprise Symphony or the Farewell Symphony. His famous good humor is all the more striking considering his often difficult upbringing.

Joseph Haydn was born in the little town of Rohrau, Austria, on 31 March 1732, the second of twelve children. His father Mathias was a wheelwright by day and a folk musician by night. He was especially fond of accompanying himself on the harp singing folk tunes, and he would often encourage his family to sing along with him.

It’s no surprise that Joseph’s talent blossomed in this idyllic, naturally musical environment. That talent would soon change his life forever. When he was six, a distant relative named Johann Matthias Frankh visited Rohrau. Frankh was a schoolmaster and choirmaster in the town of Hainburg, and he thought that Joseph would do well to become his apprentice. Joseph’s parents hoped that such training would assist Joseph in becoming a clergyman, and so they agreed to send him away. Accordingly, Joseph Haydn left home at the age of six.

The Frankh family didn’t take very good care of their brilliant new charge. He frequently went hungry and he was beaten regularly. Later in life, he remembered being embarrassed at the dirty clothing the Frankhs forced him to wear. Nevertheless, he learned the basics of music: how to play the violin and harpsichord, and, more importantly for his immediate future, how to sing.

In 1739, not long after Joseph had arrived at the Frankh house, an important musician named Georg von Reutter came to town. Reutter was the director of music at St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna, and he was on a tour of the smaller Austrian cities, scouting out new talent for his cathedral choirs. (A steady supply of boys was needed, since every year a certain percentage of their high voices fell victim to puberty.) During this scouting trip, Reutter heard Haydn and was deeply impressed, offering him a position as a chorister. In the spring of 1740, Joseph made his second big move, arriving in Vienna at the age of eight.

He worked for nearly a decade at the cathedral as a chorister. He was steeped in church music, but he didn’t receive the systematic training in theory and composition that he craved. He eventually resorted to asking his father for money to buy the famous textbook Gradus ad Parnassum so that he could start to teach himself. He also still struggled to get enough to eat. But if he sang well enough, he was invited to perform at aristocratic parties, where he was fed.

He worked for nearly a decade at the cathedral as a chorister. He was steeped in church music, but he didn’t receive the systematic training in theory and composition that he craved. He eventually resorted to asking his father for money to buy the famous textbook Gradus ad Parnassum so that he could start to teach himself. He also still struggled to get enough to eat. But if he sang well enough, he was invited to perform at aristocratic parties, where he was fed.

By 1749, Haydn’s voice was starting to break. Apparently the Empress herself referred to his singing as “crowing.” Joseph didn’t help matters when he jokingly snipped off the pigtail of a fellow chorister. Ruetter threatened to cane Haydn for his insubordination. Haydn replied that he’d rather leave the choir than be so humiliated. Ruetter replied, “Of course you will be expelled…after you have been caned.”

So it was that a teenaged Joseph Haydn found himself humiliated, fired, and homeless. Luckily an acquaintance named Johann Michael Spangler invited the young genius to share (cramped) quarters with him, his wife, and baby son. His lodging secured, Haydn started working as a freelance musician, finally gaining a certain level of control over his life after years of lonely nights, tiny meals, and hard teachers.

Haydn was clearly more than a great composer or a quick wit. He was a survivor.

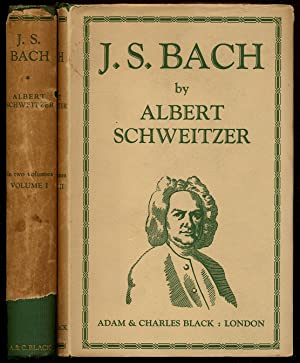

Schweitzer’s theological acumen also uniquely paved the way for his scholarly and practical interpretation of

Schweitzer’s theological acumen also uniquely paved the way for his scholarly and practical interpretation of

Arguably one of Rachmaninoff’s most famous pieces The Prelude Op. 3 No.2 is in C# minor and launched Rachmaninoff’s career after he performed this piece in 1892. Composers believe that particular keys evoke discernable and unique feelings. On the piano, this key uses many of the black keys with its slow chords, and one senses anxiety and tension from the beginning. There is a story that the inspiration for this work was a dream Rachmaninoff experienced: Set at a funeral where the coffin is prominently placed, he approaches the coffin, and to his horror he sees himself inside! That calls for a minor key!

Arguably one of Rachmaninoff’s most famous pieces The Prelude Op. 3 No.2 is in C# minor and launched Rachmaninoff’s career after he performed this piece in 1892. Composers believe that particular keys evoke discernable and unique feelings. On the piano, this key uses many of the black keys with its slow chords, and one senses anxiety and tension from the beginning. There is a story that the inspiration for this work was a dream Rachmaninoff experienced: Set at a funeral where the coffin is prominently placed, he approaches the coffin, and to his horror he sees himself inside! That calls for a minor key!

It really is too bad that Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767) did not have a large social network following! Throughout his long and industrious career, he wrote well over 3000 works. It’s no surprise that 18th-century critics unanimously considered him among the best composers of his time. Leading theorists held up his works as compositional models, and his fame extended to Holland, Switzerland, Belgium, France, Italy, England, Spain, Norway, Denmark and the Baltic lands. Yet by the early years of the 19th century, appreciation of Telemann’s music was in rapid decline. The main criticism turned out to be rather tongue in cheek. “In general,” a music historian wrote, “Telemann would have been greater had it not been so easy for him to write so unspeakably much. Polygraphs seldom produce masterpieces.” And once his music was compared according to the very different aesthetic standards of

It really is too bad that Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767) did not have a large social network following! Throughout his long and industrious career, he wrote well over 3000 works. It’s no surprise that 18th-century critics unanimously considered him among the best composers of his time. Leading theorists held up his works as compositional models, and his fame extended to Holland, Switzerland, Belgium, France, Italy, England, Spain, Norway, Denmark and the Baltic lands. Yet by the early years of the 19th century, appreciation of Telemann’s music was in rapid decline. The main criticism turned out to be rather tongue in cheek. “In general,” a music historian wrote, “Telemann would have been greater had it not been so easy for him to write so unspeakably much. Polygraphs seldom produce masterpieces.” And once his music was compared according to the very different aesthetic standards of  During his career as a composer of church music Telemann wrote at least 1700 cantatas! Always imaginative in his handling of vocal and instrumental color, Telemann’s transparent counterpoint was highly valued by his contemporaries. As you might well imagine, his cantata settings embrace a wide range of styles, forms and employment of instrumental forces. Significantly, a substantial number of Telemann’s sacred cantatas were not exclusively tied to performances in sacred venues, but could also be used for domestic devotions. In the foreword to the second collection of the Harmonischer Gottes-Dienst (Harmonic Service to the Lord) of 1731 he writes, “Two instruments of dissimilar kinds are so arranged that one person of his own can make us of the clavier without the addition of another instrument.”

During his career as a composer of church music Telemann wrote at least 1700 cantatas! Always imaginative in his handling of vocal and instrumental color, Telemann’s transparent counterpoint was highly valued by his contemporaries. As you might well imagine, his cantata settings embrace a wide range of styles, forms and employment of instrumental forces. Significantly, a substantial number of Telemann’s sacred cantatas were not exclusively tied to performances in sacred venues, but could also be used for domestic devotions. In the foreword to the second collection of the Harmonischer Gottes-Dienst (Harmonic Service to the Lord) of 1731 he writes, “Two instruments of dissimilar kinds are so arranged that one person of his own can make us of the clavier without the addition of another instrument.” Telemann is known to have composed approximately 125 orchestral suites, 125 concertos, several dozen other orchestral works and sonatas in five to seven parts, nearly 40 quartets, 130 trios, 87 solos, 80 works for one to four instruments without bass and roughly 250 pieces for keyboard. Now that’s what I call a life’s work! For the most part Telemann wrote his instrumental works for small performing forces, making them appropriate for domestic use. Historically significant, Telemann popularized the French-style orchestral suite in Germany paving the way for the works of J. S. Bach and others. Telemann was a kind and gentle man capable of witty humor, so entire works or individual movements have amusing programmatic titles. The Suite Burlesque de Quixotte includes the famous attack on the windmills, and the Suite La Bourse offers a musical account of the Parisian stock market crash of 1720!

Telemann is known to have composed approximately 125 orchestral suites, 125 concertos, several dozen other orchestral works and sonatas in five to seven parts, nearly 40 quartets, 130 trios, 87 solos, 80 works for one to four instruments without bass and roughly 250 pieces for keyboard. Now that’s what I call a life’s work! For the most part Telemann wrote his instrumental works for small performing forces, making them appropriate for domestic use. Historically significant, Telemann popularized the French-style orchestral suite in Germany paving the way for the works of J. S. Bach and others. Telemann was a kind and gentle man capable of witty humor, so entire works or individual movements have amusing programmatic titles. The Suite Burlesque de Quixotte includes the famous attack on the windmills, and the Suite La Bourse offers a musical account of the Parisian stock market crash of 1720!