by Georg Predota , Interlude

“There are only two means of refuge from the miseries of life:

Music and Cats!”

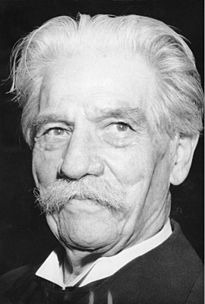

Albert Schweitzer

For many of us mere mortals, it seems utterly unfair that some fortuitous individuals should inherit multiple talents and abilities. Take for example the polymath genius Albert Schweitzer, who made major scholarly contributions to theology and music in the early years of the twentieth century. Not satisfied, he abandoned his academic career and established a medical mission in Africa, a legacy of humanitarian service that is still active today.

Schweitzer was born 14 January 1875 in Kayserberg in Upper Alsace, the son of a Lutheran pastor. He took organ lessons at an early age, and started private lessons with the famed Parisian organist Charles-Marie Widor in 1893. His passion for organ music was paralleled by a fascination with theology and he concordantly entered Strasbourg University to study theology and philosophy. He submitted a dissertation on the philosophy of Immanuel Kant to earn the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in July 1899, followed by a Doctorate in Theology with a dissertation on the “Last Supper” in 1900. A second work, “A Sketch of the life of Jesus” was published in 1901 and challenged the secular view of Jesus. His multiple writings reviewed, summarized and critiqued a vast corpus of research into the Life of Jesus that stressed the distance between the historical Jesus and contemporary views that saw Jesus detached from the cultural context of Judaism. For many thinkers, his greatest contribution to humanity was his quest for a universal ethical philosophy. Following the military use of nuclear weapons on Japan’s civilian population, Schweitzer felt that Western civilization was inexorably decaying because it had abandoned affirmation of life as its ethical foundation. His most influential discourse, “Reverence for Life” not only laid the theoretical foundation for his personal missionary works in Africa, it also gained him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1952.

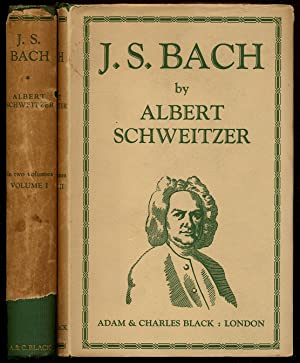

Schweitzer’s theological acumen also uniquely paved the way for his scholarly and practical interpretation of J.S. Bach’s music. He began to explore the use of pictorial and symbolical representations in Bach’s Chorale Preludes, in which harmonic language, musical motifs and rhythmic figures illustrate the actual words of the hymns on which they were based. At the instigation of Widor, Jean-Sebastian Bach: Le Musicien-Poète was published in 1905 and presented a critical study of Bach’s music based on devotional contemplation in which the musical design corresponded to literary ideas and was visually represented in the score. Originally published in French, great demand in Germany prompted Schweitzer to rewrite his study and he eventually published two greatly expanded German volumes in 1908.

Schweitzer’s theological acumen also uniquely paved the way for his scholarly and practical interpretation of J.S. Bach’s music. He began to explore the use of pictorial and symbolical representations in Bach’s Chorale Preludes, in which harmonic language, musical motifs and rhythmic figures illustrate the actual words of the hymns on which they were based. At the instigation of Widor, Jean-Sebastian Bach: Le Musicien-Poète was published in 1905 and presented a critical study of Bach’s music based on devotional contemplation in which the musical design corresponded to literary ideas and was visually represented in the score. Originally published in French, great demand in Germany prompted Schweitzer to rewrite his study and he eventually published two greatly expanded German volumes in 1908.

Albert Schweitzer’s published writings on J.S. Bach

As a performer, Schweitzer was constantly in search of “clarity of expression.” Growing up in Alsace, he had experienced the sleek, colorful and highly characteristic sounds of the organs produced by Gottfried and Andreas Silbermann, the most famous and influential instrument builders active during J.S. Bach’s lifetime. For performances of Bach’s music therefore, Schweitzer advocated a move away from the large Romantic instruments of the 19th Century and called for more refined instruments suited to Baroque music. The Art of German and French Organ Building and Organ Playing was published in 1906, and not only laid the foundation for the modern-day instruments, but also aided in his personal restoration of the Organ at St. Aurelie in Strasbourg, which produced his famous 1936 recording of Bach’s “Chorale Preludes.” Prior to his departure for Africa in 1912, Schweitzer founded the Paris Bach Society, and published a new edition of Bach’s organ works with detailed analysis of each work in three languages. After eight grueling years of study, Schweitzer also qualified as a medical doctor with a specialization in tropical medicine and surgery, and he began to raise private funds for the establishment of a hospital based at Lambaréné in the French Congo. Schweitzer was a harsh critic of colonialism, and his medical mission was his response to the “injustices and cruelties people have suffered at the hands of Europeans.” Until his death in 1965, Schweitzer continued to publish, lecture, perform and care for the sick. He apparently did so in the company of his two cats, “Sizi” and “Piccolo.” According to legend, his cats liked to sleep in the middle of his desk and if someone needed some papers, “they were required to wait until the cats woke up.” However you’d like to describe Albert Schweitzer — intelligent, articulate, compassionate, musical, spiritual or ethical — we could certainly do worse then to aspire to his level of humanity.

No comments:

Post a Comment