In historical studies of music, compositions by children have generally not been held in high regard. The one exception, of course, is Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, “commonly regarded as the child composer par excellence.” While the focus has so far been on childhood works by major composers, a recent publication by Barry Cooper has suggested, “that we might well look at the major works of all child composers regardless how they developed in later life.” And while it is easy to imagine a child composer writing a short song or piano piece, I was particularly interested in child composers producing large-scale compositions before the age of 16.

Johann Nepomuk Hummel

Johann Nepomuk Hummel

So let’s get started with our little survey of child prodigy composers with music by the 14-year-old Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778-1837). Hummel studied with Mozart between the ages of eight and ten, and he composed a number of variations under Mozart’s tutelage. Once Hummel had moved to London, he published three sonatas for piano or harpsichord, two of them with violin or flute accompaniment. Hummel was only 14 at the time, “and he attracted a huge number of subscribers from London, Vienna, Prague, and countless other cities.

Gioachino Rossini

Gioachino Rossini

Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868) composed six string sonatas at the age of twelve in 1804. Scored for the unusual combination of two violins, cello, and double bass, “they are among the most successful works ever written by any child.” Rossini was familiar with the works of Mozart and Haydn, but it still seems incredible how these sonatas anticipate much of the sparkle of his later works. He composed them for a young merchant and claimed to have been ignorant of harmony when he wrote them. Actually, he described them as “horrendous,” and claimed to have written them within three days. However, Rossini could not deny his own personal style, including a characteristic melodic style, the use of crescendos, and the occasional use of the double bass as a kind of buffo character. These sonatas do show some surprisingly inventive and unusual features, “including unexpected keys and modulations, and spiced up percussive cross-relations.”

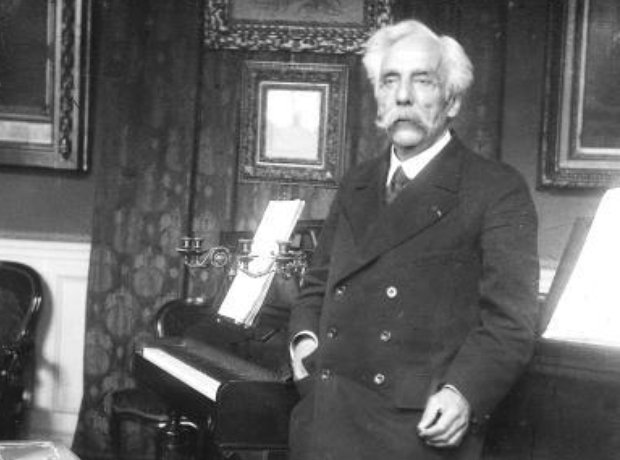

Georges Enescu

The young Georges Enescu at 3 years old

Yehudi Menuhin described Georges Enescu (1881-1955) as “the greatest musician I have ever experienced.” Such high praise is actually not surprising as Enescu had composed at least fifty works by the time he reached the age of sixteen. Almost habitually, a composer’s career is viewed as one of growth and improvements, “with the implication that early works have little or no interest.” They are often dismissed as “juvenilia,” and accorded a secondary place within the overall oeuvre. Suggestions of immaturity and youthful doodling, however, are completely out of place when speaking of Enescu. By 1895, if not before, he was “already a thorough master of the art of composition.” Enescu composed 4 Study Symphonies, and Massenet described the first symphony in D minor, as “very remarkable, extraordinary for his instinct for development.” As Cooper observes, “none of the works produced before 1897 seem to have been written with publication in mind, and indeed nearly all of them are still unpublished, though thankfully Enescu preserved the manuscripts of most of them and they are now in the Enescu Museum in Bucharest.

Frederick Arthur Gore Ouseley

Frederick Arthur Gore Ouseley

I must confess that before reading Cooper’s book on children composers, the name Frederick Arthur Gore Ouseley (1825-1889) was not known to me. As it turns out, Ouseley is “possibly the youngest child ever to compose a complete and coherent piece of music that still survives.” According to an anecdote, a very young Ouseley famously asked his father why he blew his nose in G. His father had been ambassador to Russia and Persia, and his earliest work is dated 18 November 1828, when he was aged three years and ninety-eight days. It was published many years later. These early pieces were written down by his sister Mary Jane, as Ouseley began composing long before he learned to write, “but his sister appears not to have attempted to correct his music in any way. Ouseley composed his first opera, Tom and His Mama in 1832, and most of his childhood compositions still survive, albeit only in manuscript. None of these early pieces seem to have been properly recorded. As such, I decided to feature a Prelude and Fugue written during his tenure as Vicar of St. Michael’s Tenbury as well as Warden of the College.

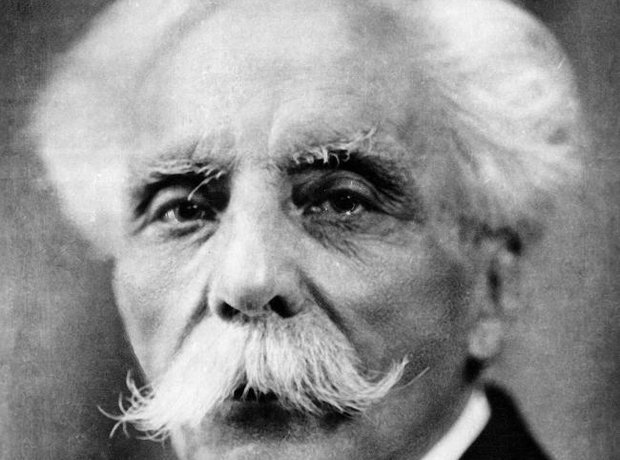

Muzio Clementi

Muzio Clementi

Musicologists have discovered that Muzio Clementi (1752-1832) composed a full-scale oratorio at the age of 12. The libretto does survive in a printed source of 1764, but the music has sadly been lost. It’s almost certain that there must have been a number of additional compositions, “as the oratorio is most unlikely to be the first thing he ever wrote. Clementi’s earliest surviving work is the Sonata per cembalo in A flat major, dated 1765. The music was not published in the composer’s lifetime, but it is identified “on the manuscript as No. 20, suggesting Clementi’s prolific activity as a composer at the age of thirteen.” In three movements, the sonata, typical in many ways of its period, demonstrates Clementi’s early technical competence, with an opening classical Allegro, followed by a contrasting slow movement and a rapid finale. As a critic writes, “The sonata is a well-constructed work in which each movement explores the structural distinction between binary form and sonata form in a different way. The finale is particularly successful, with broken-chord motifs exploited in a variety of ways.”

Samuel Wesley

Samuel Wesley

Samuel Wesley (1766-1837) was the younger son of the divine and hymn-writer Charles Wesley (1707-1788), “the sweet singer of Methodism,” and a nephew of John Wesley, the evangelist and leader of Methodism (1703-1791). Samuel appears to have been one of the most prolific and gifted of all child composers, “as he composed more than one hundred works by the age of sixteen. By the age of eight, Wesely had crafted the oratorio Ruth, even though it was reported that much of the work had been composed up to two years earlier. A second oratorio was completed shortly thereafter. The “Sinfonia Obligato” for violin, cello and organ, with an orchestra of strings and two horns, with ad libitum timpani is dated 27 February 1781. The unusual solo grouping is used in the outer movements, and the technical demands on the three players are considerable. As Cooper observes, “By the age of sixteen Wesley had a formidable basis for developing into a truly great composer, unfortunately, he did not fulfill his potential, and the reason may be largely his own fault.” In addition, a head injury and lack of proper training prevented him from achieving his full potential.

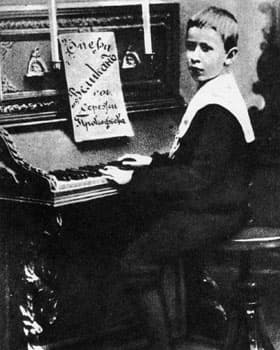

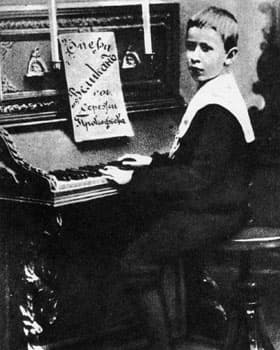

Sergei Prokofiev

Sergei Prokofiev in 1900

Sergei Prokofiev’s (1891-1953) early compositions already show a preference for ostinato and terrifying effects. His earliest known composition is titled “Indian Galop,” and dates from the summer of 1896. As in many cases with child composers, his mother wrote it down, as the child had not yet grasped musical notation. Prokofiev continued to compose further piano pieces throughout his childhood, totaling roughly eighty works by the time he reached the age of sixteen. By 1902, Prokofiev had completed a symphony in G with the help of his teacher Reinhold Gliére. “Altogether, sixty-one pages of this symphony survive in score, including a fully orchestrated first movement and the rest in short score.” As has been suggested, however, more significant than his instrumental compositions were his early attempts at writing operas. Velikan (The Giant) dates from February to about June 1900. It is written in vocal score and divided into three acts of seven scenes. “Velikan is notable for some extreme dynamics and some powerful music for the Giant, whose footsteps are portrayed by loud, ponderous chords that uncannily foreshadow the heavy chords accompanying the main theme in ‘The Montagues and the Capulets’ in Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet.”

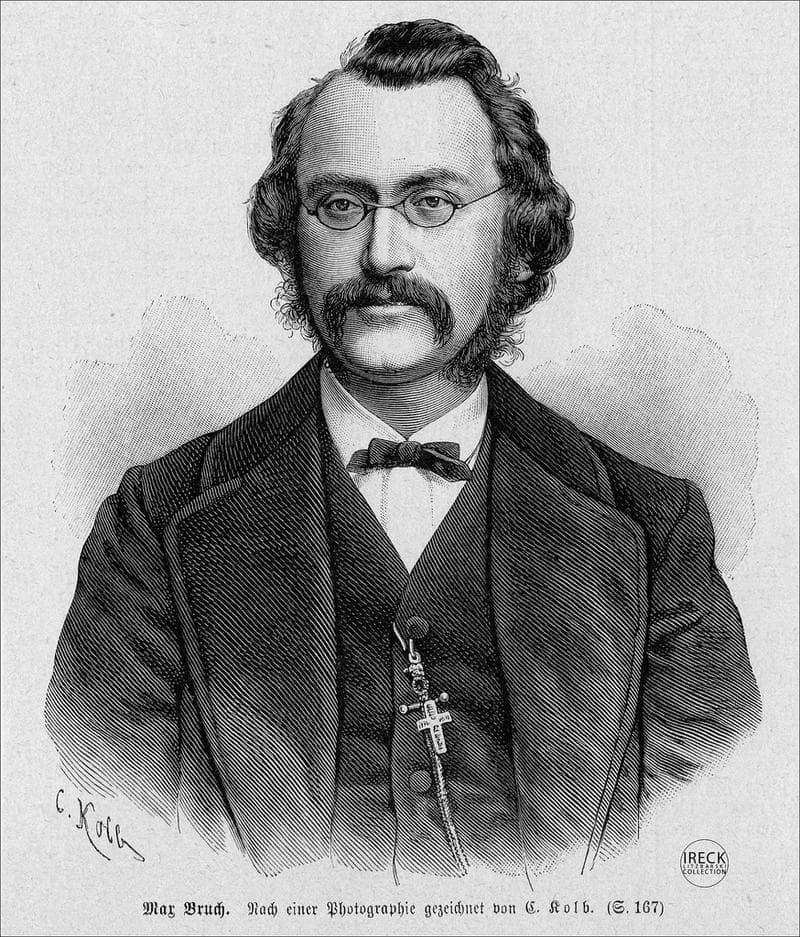

Max Bruch

Max Bruch

The Septet in E-flat Major by Max Bruch (1838-1920) was only published in 1987, but it was composed in 1849, when Bruch was only 11 years old. Apparently, his first composition was written at the age nine for his mother’s birthday. “Soon he composed prolifically, producing motets, psalms, piano pieces, violin sonatas, a string quartet, and even orchestral works while still a child.” Almost all these early works, which also include two piano trios and lieder, have been lost. The four movements of the septet, scored for clarinet, horn, bassoon, two violins, cello, and double bass, reveal a surprising maturity. His innate musical sensitivity allowed him to orchestrate and create melodic inventions with consummate skill. Remarkable for a composer his age, Bruch creates enchanting effects, which are in marked contrast to the virtuoso elements of the work. Without doubt, this youthful composition “bears clear features of Bruch’s later style, and much skill in form and harmonic planning.”

George Frideric Handel

George Frideric Handel

George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) apparently composed prolifically during his childhood. He is said to have written weekly compositions for the church in Halle, but none of these early works have seemingly survived. As with many other works of Handel, we are dealing with questions of authenticity when it comes to his childhood works. He is supposed to have written six oboe sonatas at the age of eleven, “works that display occasional touches of originality.” When Handel was shown a copy of the sonatas in England many years later, he actually confirmed the authenticity of the Sonatas. He also confessed that he enjoyed writing music for the oboe. “Since they do not differ greatly in style from his later music, there seem no very reliable grounds, external or internal, for dismissing the attribution to Handel, as have been done by several recent scholars.” What makes these early works suspicious, I suppose, is that the “exhibit characteristic melodic imagination and contrapuntal skill along with Handel’s renowned ability at developing whole movements out of two or three seemingly insignificant motifs.”

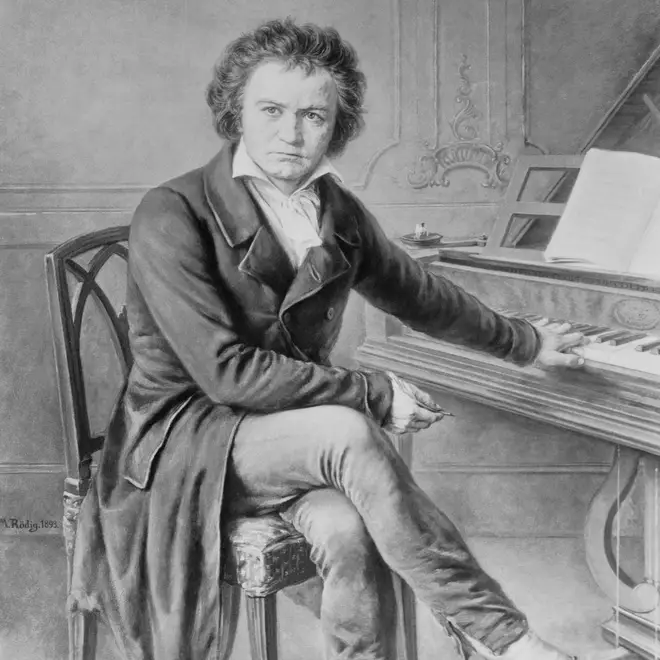

Ludwig van Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven at 13 years old

Let us conclude this first episode dedicated to child composers with Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827). Many of his childhood compositions are said to be derivative of works by Mozart, however, Beethoven employs a much wider dynamic range, and much more virtuosic piano figuration. When he attached a dedicatory letter to the 1783 original edition of his three early piano sonatas (WoO 47), he explained that his Muse had commanded him to write down his music. “My Muse wished it, and I obeyed and wrote.” According to Cooper, “This sense of compulsion experienced by some composers provides further evidence for an innate, genetic predisposition to composition in a few rare children, rather than a response to an external incentive.” Beethoven’s E-flat Major Piano Concerto WoO 4, was written when the composer was fourteen years old. To enhance his son’s reputation as a prodigy, Beethoven’s father claimed that the work was written when the boy was only 12. “Beethoven was not aware of this false claim until he was 40 years old, by which time he had long since disowned the piece.” The music for this work survives in only the solo piano part, and various scholars, musicologists, and performers have since reconstructed the entire concerto. A scholar writes, “While it is difficult to regard the E-flat concerto in its standard arrangement as an authentic piano concerto by Beethoven, the parentage of the solo piano manuscript is undisputed.” Please join us next time, when we will showcase early compositions by Mozart, Mendelssohn, Clara Wieck, Richard Strauss, and others.