Zero Gravity Proposal

Who said romance was dead? Well, clearly it hasn’t died but simply been updated in the Instagram era. Many of my friends find it very romantic for their partner to tag them in a photo in Instagram or Facebook. They also consider it romantic for their partner to create a Spotify playlist for them, and it is considered romantic to watch something on Netflix together. It seems a bit cliché to get engaged on Valentine’s Day, but for many people, it’s still the perfect day for a marriage proposal. Google analytics tells us that there are an average of 12,000 searches each month on “how to propose.” But in February, around Valentine’s Day, that number jumps to 22,000. “Will you marry me?” is a simple question, but it turns out there are lots of innovative ways to ask it. Just do a quick Youtube search on the weirdest, most wonderful or most bizarre marriage proposals, and you’ll be treated to the whole gamut of human ingenuity.

Victorian Bride and Groom

There is the “Back from the Dead Proposal,” “The Music Video in Your Pants Proposal,” “The Zero Gravity Proposal,” “The Dancing Carrots Proposal,” “The Roller Coaster Proposal,” or the “Stand on an active Volcano Proposal.” I think you get the point. I must have literally watched hundreds of unusual ways of popping the question, and to my surprise, music plays an important role in many of them. But even more importantly, music becomes an essential part of the wedding celebration itself. And since I like Classical Music, I’ve decided to put together a list of Classical Music connected with that very special day.

If you are considering a church wedding, there is a good chance that the organ, the piano, string quartet, or electric guitar will sound one of two stock wedding pieces. One is the “Wedding March” by Felix Mendelssohn, and the other is the “Bridal Chorus” from the 1850 opera Lohengrin by Richard Wagner. Both are generally played for the bride’s entrance to formal weddings, and in English-speaking countries we know the Wagner tune as “Here Comes the Bride.” The actual words, written by Wagner himself, read:

Faithfully guided, draw near

to where the blessing of love shall preserve you!

Triumphant courage, the reward of love,

joins you in faith as the happiest of couples!

Champion of virtue, proceed!

Jewel of youth, proceed!

Flee now the splendour of the wedding feast,

may the delights of the heart be yours!

Wagner expressed some lovely sentiments, indeed, but the big surprise comes in the second verse. The women of the wedding party sing the actual “Bridal Chorus” after they accompany the heroine Elsa to the bridal chamber. Next time you hear that tune, remember that it marks the entrance to the bedroom!

This sweet-smelling room, decked for love,

now takes you in, away from the splendour.

Faithfully guided, draw now near

to where the blessing of love shall preserve you!

Triumphant courage, love so pure,

joins you in faith as the happiest of couples!

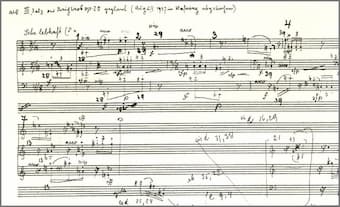

Edvard and Nina Grieg

One of the most uplifting and most popular pieces connected with the big day is Edvard Grieg’s “Wedding Day at Troldhaugen.” Troldhaugen is not a Norwegian city or district, but actually the name of the house Edvard Grieg shared with his wife Nina. Located near the city of Bergen, Norway, the unusually house name combines the words “trold” meaning troll, and “haug” originating from an Old Norse word meaning hill. Grieg said that local children called the nearby small valley “The Valley of Trolls,” and he thus gave the name to his building. It was actually designed by Grieg’s cousin, the architect Schak Bull, and Grieg called the building “my best composition.”

Troldhaugen, home of Edvard and Nina Grieg

Troldhaugen is a fairly typical 19th century residence with a panoramic tower and a large veranda. The small composer’s hut located nearby overlooks Nordås Lake, and the entire estate now operates as the Edvard Grieg Museum Troldhaugen. But what about the “Wedding Day?” Grieg composed this miniature to commemorate his 25th wedding anniversary. It is part of a collection titled Lyric Pieces, which the composer started after he finished his studies in Leipzig. Together with the Danish composer Christian Emil Horneman, Grieg started a music company with the principle aim of creating a forum for new Scandinavian music. A couple of years later, the “Nordic Music Magazine” enlisted the Swedish composer August Söderman and also Edvard Grieg. In all, Grieg composed 66 “Lyric Pieces,” and he once wrote “I honestly haven’t done anything, other than the so called “Lyrical Pieces,” which are surrounding me like lice and fleas in the country.” And by the way, Edvard and Nina are still together as their ashes were placed in a mountain tomb near Troldhaugen.

Maxwell Davies: Orkney Wedding with Sunrise

The music of Sir Maxwell Davies (1934-2016), according to scholars, “has a depth of symbolism and historical reference rarely encountered elsewhere in contemporary music.” One of the foremost composers of our time, Davies has cultivated a number of styles, ranging “from the unbridled Expressionism of his music-theatre pieces of the late 1960s to the majestically unfolding landscapes of his later orchestral works.” For his Orkney Wedding with Sunrise, Maxwell Davies takes us to Scotland to provide us with a picture postcard record of an actual wedding he attended on Hoy in Orkney. The composer writes, “At the outset, we hear guests arriving, out of extremely bad weather, at the hall. This is followed by the processional, where the guests are solemnly received by the bride and bridegroom, and presented with their first glass of whisky. The band tunes up, and we get on with the dancing proper. This becomes ever wilder, as all concerned feel the results of the whisky, until the lead fiddle can hardly hold the band together any more. We leave the hall into the cold night, with echoes of the processional music in our ears, and as we walk home across the island, the sun rises, over Caithness, to a glorious dawn. The sun is represented by the highland bagpipes, in full traditional splendor.” Partying the night away with music and plenty of whisky while waiting for the sunrise seems like a great way to celebrate a wedding.

Carl Goldmark

The Hungarian composer Carl Goldmark (1830-1915) was famous for his opera The Queen of Sheba. According to a rather infamous anecdote, an older lady asked Goldmark how he made his living. “I am a composer,” he said, “I am the composer of The Queen of Sheba.” “Ah-yes,” the lady responded, “but does the post pay well?” However, when the opera premiered in 1875 in Vienna, Goldmark was the talk of the town. A critic wrote, “ever since 1875, Goldmark has been recognized as the only thoroughly successful German opera composer since Richard Wagner.” Goldmark also dabbled in orchestral compositions, and he left two symphonies, a number of concert overtures, a violin concerto and two symphonic poems, including the “Rustic Wedding.” The work premiered in 1876, and unfolds in five descriptive movements. It predictably starts with the “Wedding March,” with a simply theme subjected to a number of colourful variations. Initially, we hear the rustic theme in the lower strings, and it resurfaces in the winds for the first variation. The strings take over in the lyrical second variation and lead the theme to a cheerful outburst. We are treated to a dramatic minor key version of the melody, and a fanfare returns us to the original “Wedding March.” A tender Intermezzo titled “Nuptial Song” is followed by a light and airy “Serenade.” Subsequently, we are invited to witness a loving dialogue between the bride and groom in the “Garden,” and a cheery “Dance” combining rustic festivities concludes this picturesque work. It is not surprising that this vividly atmospheric symphonic poem was greatly championed by Leonard Bernstein and by Sir Thomas Beecham.

The Language of the Birds (Burgtheater, Vienna)

On 22 March 1911 Jean Sibelius received a telegram from the Swedish playwright Adolf Paul asking for music for his new play. He writes, “Dear Janne, do me the great favour of writing music for my new play… It’s called The Language of the Birds. The main role is Solomon, the heroine is Abishag from Shunem! (You know, the one who was brought to old King David to warm up his dying flames of life, and who was later given by Solomon to his friend Sabud, as his wife.) Just one piece of music, Oriental, drums, harps, cymbals, flutes and other stuff. To be heard first from inside the palace where she is being dressed for the wedding, then the wedding procession approaches (lots of eunuchs and court servants, the whole thing takes five minutes at most).”

Adolf Paul

More specifically, Paul wanted music for the wedding procession in Act II, in which Abishag arrives to marry Solomon. He imagined “the carpets covering the doorway are drawn aside. Out of the distance comes sound of trumpets, flutes and cymbals gradually nearing. The wedding procession approaches. First the musicians with harps, flutes, and cymbals, the girls, strewing flowers, then Abishag, splendidly attired with the royal circlet on her brow, the attending women, and last of all the Palace Chamberlain, all with palm branches in their hands. Solomon standing erect in front of throne, gazing with triumphant mien at spectacle. Just as procession has reached steps of throne, he stretches out his hand commandingly. Abishag falls back a step. All stop. Music ceases.” Sibelius did compose the music in the summer of 1911, but his music “has never been performed together with the play, although numerous attempts have been made.” Sibelius writes in his diary, “It may not be stupefying but it is interesting in the manner of modern commissioned stuff. It is natural and effective in its scoring, and not without poetry.”

Caroline Montigny-Rémaury

Since every wedding needs a cake, Camille Saint-Saëns provided a musical one for the nuptial of pianist Caroline Montigny-Rémaury. She was student of

Franz Liszt, and sister-in-law of Ambroise Thomas, director of the Paris Conservatoire. Saint-Saëns’

Wedding Cake was presented on the occasion of her second marriage in 1886, as she proudly became Caroline de Serres Wieczffinski.

For me personally, Pascal Rogé is one of the great interpreters of French piano music. For several years, Pascal has enjoyed playing recitals for four hands and two pianos with his partner in life and in music, Ami Rogé. They got married in Shimonoseki, Japan on 8 March 2009, and have travelled the world together appearing at prestigious festivals and concert halls. Rogé writes, “I have always said that my ambition was to play the music I love with the people I love; this has never been more true than today, since I have met Ami. With her I have been able to continue my search of sounds and colours throughout the French repertoire, but now with four hands and two hearts. I believe that the love we share every day in our life together is an inspiration for interpreting the music, and I feel as though our emotions could transform a double black and white piano recital into a single colourful dream.” On a recent tour of Japan they performed the premiere of the

Ami Suite, a work for four hands specifically written for them by the Japanese-American composer Paul Chihara. The composer writes,

Ami is in five movements, which outlines a story. The first movement is like a piano lesson, or musical game, between two pianists just meeting. It is fun and bouncy, and a touch academic… Movement two is a “Love Song,” the soul of Ami.

© brideandbreakfast.hk

It is in the style of an American pop ballad, with references to Tristan und Isolde and the Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune. Movement three is the “Pascal Rag,” a portrait of the male protagonist in this romantic comedy. It is youthful and confident, and filled with love for his musical partner, whose music is full of counterpoint and commentary… The fourth movement, “Aka Tombo” (Dragonfly), is based on the well-known and beloved Japanese folk song of the same name. It travels through many keys and transformations, suggesting the discovery and adventure of new love. The final movement is the longest and most complex of all the movements. Its emotionally troubled first theme is in the minor, leading to a quote from the wonderful Poulenc Piano Concerto. The clouds soon part when the “Love Song” from the second movement returns, more romantic and developed than before. This leads in turn to the original “game theme” from the first movement, then to the happy cowboy melody, now gloriously transformed and joyous. The piece ends with a final, quiet version of the love theme, in the intimate key of A-flat: a happy ending.