by

Pierre-Auguste Cot: Springtime

I have never been that interested in American country music, because I naively connected it with bar fights, drinking whisky and plenty of flag waving. To be sure, it has nothing to do with the music or the lyrics, but my dislike was primarily based on my own unfamiliarity with the many styles and subgenres. I read that many of the country ballads had their origin in the “folk music of working class Americans and blue-collar American life, but that it can also touch on cowboy Western music, Southern gospel and spirituals, and other influences.” A good many ballads deal with overcoming hardship, family pride, heartbreak, and love. Basically, it all is very down to earth, and I’ve come across some lyrics that perfectly express what the celebration of Valentine’s Day is all about.

Pierre Auguste Renoir:

Country Dance

It’s amazing how you can speak right to my heart

Without saying a word, you can light up the dark

Try as I may I can never explain

What I hear when you don’t say a thing

The smile on your face lets me know that you need me

There’s a truth in your eyes saying you’ll never leave me

The touch of your hand says you’ll catch me wherever I fall

You say it best, when you say nothing at all

Notting Hill is a district of West London, known for its diverse communities and long association with artists. It provides the backdrop for bookshop owner William Thacker and famous Hollywood actress Anna Scott to fall in love. In the featured clip, the stars of the film, Julia Roberts and Hugh Grant do a marvelous acting job expressing emotional love in a non-verbal way. As viewers we immediately understand these emotions, and of course it helps to hear the music and the appropriate lyrics at the same time. Music can help us to express emotions that are hard to verbalize, “we are compelled by it, moved by it, and inspired by it.” Music certainly has the ability to touch us in very special ways, and it has frequently been described as “the language of emotions.”

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Neither love nor music actually needs words to express significant emotions, and one of the most intimate forms of classical music sounds in the combination of two instruments. While the term “Duet” is frequently applied to pieces for two voices, the “Duo” is primarily considered an instrumental work. As you lovingly gaze into the eyes of your beloved on Valentine’s Day 2022, you might consider reinforcing your emotional bond with some Duo music. And what better way to start than with a duo for violin and viola composed by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Mozart composed this duo during a rather stressful time in his life in the summer of 1783. For one, he had just been fired from his Salzburg job by getting a “kick in the behind” from Count Arco, the chief steward of Archbishop Hieronymus Colloredo. Additionally, against the expressed wishes of his father, he had hurriedly married Constanze Weber in Vienna. In 1738, Mozart returned to Salzburg to introduce his new wife to his father, which went surprisingly well. Mozart also met his old friend, the court music director Michael Haydn. Sadly, Haydn was suffering from a long and severe illness and was unable to complete the Archbishop’s commission for six duos for violin and viola. Always the tyrant, the Archbishop threatened to cut off Haydn’s salary until the two remaining duos were complete. As such, as a favor to his old friend and deeply in love with his wife, Mozart composed the missing duos and gave them to Haydn to pass off as his own. The Archbishop, believing them to have been composed by Haydn, was full of praise. In the G-major duo, Mozart treats both instruments as equal partners in the musical discourse, and in the lyrical slow movement he expressed his lifelong love of opera, the human voice, and for his wife Constanze.

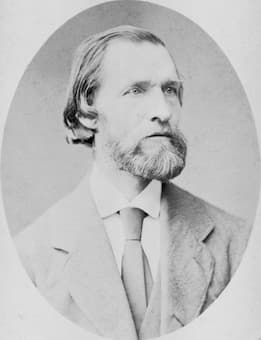

Friedrich Hermann

Friedrich Hermann (1828–1907) was one of the first students at the newly established Royal Conservatory of Music in Leipzig. Founded in 1843 by Felix Mendelssohn and Moritz Hauptmann, the institution responded to the growing professional demands of musical life in Germany. All its resources were aimed at meeting the demand for highly skilled orchestral musicians, instrumental soloists and opera singers. However, there was also a need for music teachers to serve the expanding middle class, especially in piano and vocal training. Hermann entered the Conservatory as a violinist, violist, and composer and studied with Moritz Hauptmann, Niels Wilhelm Gade, Felix Mendelssohn- Bartholdy, and Ferdinand David. How is that for an impressive line-up of teachers for your resume? Ferdinand David wrote of Hermann that he “worked diligently and with good conduct, and that he deserved the highest praise. Upon graduation, Hermann became first violin of the Leipzig Orchestra, and in 1847 joined the Conservatory as a Professor. A member of the Gewandhaus Quartet, he also became an important editor for the companies of Peters and Augener, and he composed a symphony, a quartet for wind instruments, and various other works. Among them is a delightful Grand Duo Brilliant for Violin and Cello, published in 1858. Scored in three movements, the work is full of romantic tendencies, and the meditative “Adagio” surly speaks the language of love. We don’t know if Hermann had a specific love interest in mind, but we do know that it was dedicated to one of the great violinists and composers of the mid-nineteenth century, Louis Spohr.

Talking about Louis Spohr. He was a man with an insatiable love of life and thirst for knowledge about everything and everyone. He loved to attend parties, was a gifted painter and enthusiastic rose-grower. A keen swimmer and hiker, Spohr played chess, billiards, dominoes and all matter of ball games. He loved to visit cultural attractions, arts galleries and churches, but he also toured factories, mines and industrial installations. In addition, Spohr had an enormous reputation during the 19th century as a composer, violin virtuoso, conductor and teacher. He traveled to Switzerland, Italy, and even took on a job in England with the London Philharmonic Society; the public absolutely adored him. For his contemporaries he was equal to Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven and ranked among the greatest composers of his time.

Dorothea Schneider

One day, as he was visiting the town of Gotha he “heard a young girl execute a difficult harp fantasy with the greatest confidence, and with the finest shades of expression. I was so deeply moved,” he writes, “that I could scarce restrain my tears. Bowing in silence, I took my leave; but my heart remained behind!”

That young girl turned out to be Dorothea Schneider, and she would eventually be remembered as the premiere harp virtuoso of the early nineteenth century. Spohr soon became Dorothea’s accompanist, and one day they rode to a venue in a carriage together. “Thus alone for the first time with the beloved girl, I felt the impulse to make a full confession of my feelings towards her; but my courage failed me, and the carriage drew up, before I had been able to utter a syllable. As I held out my hand to her to alight, I felt by the tremor of hers, how great had also been her emotion.” Spohr eventually married Dorothea in 1806, and his deepest emotions are expressed in his Duo for Violin and Harp—you say it best, when you say nothing at all.

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) finished his Sonata for Violin and Cello in 1922, and he initially simply called it “Duo.” While string duos are often lightweight pedagogical works, “this piece is a tour-de-force, the thinned instrumentation highlighted by blazing string crossings, piercing harmonics, and snapping pizzicatos.” Ravel wrote, “This sonata marks a turning point in my career. The music is stripped to the bone. The allure of harmony is rejected and more and more there is a return of the emphasis on melody.“ Ravel had started his “Duo” in 1920, following the First World War. He had been desperate to join the armed forces, and tried to enlist with the French infantry. However, he came in two kilos under the official weight limit. So he passed his driving test and was declared fit for service as a truck driver. Ravel delivered supplies under artillery fire at Verdun and wrote, “For a whole week I have been driving days and nights – without lights – on unbelievable roads, often with a load double what my truck should carry. And even so I had to hurry because all this was within range of the guns.” Ravel had always harbored ambitions of joining the flying corps, but a diagnosed heart condition made that impossible. While his Sonata does leave Romantic yearning and lushness far behind, it nevertheless looks back tenderly to the memory of Claude Debussy, who had died in 1918, and to whom the work is dedicated. In addition, the two musical voices are united as they speak with one voice against the travesty of war.

Reinhold Gliére (1875-1956) is frequently described as “among the vast torrent of Russian second-raters who had long and distinguished teaching careers yet remained competent composers without much individuality or distinction manifest in their music.” That assessment sounds a bit harsh to me, because Gliére had a well-known gift for expressive melodies and colorful orchestration inspired by Russian folklore. Composing during the early days of the young Soviet Union, his music found favor with the political establishment, and Stalin and his cultural ministers appointed him chairman of the organizing committee of the Soviet Composer’s Union. As such Gliére is almost exclusively described as a political composer. In reality, however, he seems to have been a non-political person and he was certainly conservative as a musician. He was repeatedly criticized for his lack of interest in politics, but he had a special gift of writing music for the cello. His Cello Concerto, Op. 87 is the first-ever Soviet Russian cello concerto and, like so many others, it was dedicated to Mstislav Rostropovich. In 1909 he composed his intimate Eight Duets for Violin and Cello, Op. 39, and in 1911 he wrote Ten Duets for Two Cellos, Op. 53. This composition is considered one of the few original cycles for this delightful combination, “and while their form and harmony could not be called ground-breaking, Gliére’s melodic richness and talent in his skill to make two string instruments sound like an orchestra, is unique.”

Francis Poulenc

Enter Francis Poulenc, who composed his Sonata for Clarinet and Bassoon between August and October 1922. Tellingly the work is dedicated “to Madame Audrey Parr.” We know that Poulenc’s personality, psyche, music, and sexual behavior contained contrasts and contradictions that were not alternating but simultaneous. Is it too far-fetched to describe his sonata as an onlooker’s musical description of the Claudel-Audrey relationship?

Carl Maria von Weber

Please allow me to conclude this Valentine’s Day article with a movement composed by one of the most significant composers of the Romantic era. Carl Maria von Weber (1786-1826) is best known for his romantic operas, but he also composed a number of intimate pieces for the clarinet. His Grand Duo Concertant might not be the greatest duo in the history of music, but just listen how the musical lines intertwine in the language of love. And as in real life, there has to be a bit of bravado and drama. Of course it helps that the piece is performed by two of the hottest artists on the concert stage today. Music can communicate a whole myriad of expressions and feelings without the aid of spoken words. Nevertheless, you should still say “I Love You,” and buy some flower and presents for your beloved on Valentine’s Day .

No comments:

Post a Comment