Most violinists and musicians are familiar with the beautiful series of violin concertos, The Four Seasons, crafted by the master baroque composer Antonio Vivaldi. However, not everyone is familiar with some of the most interesting aspects of his life. One of which is that this musical genius narrowly missed being buried in oblivion more than once.

Vivaldi must have been destined for greatness by virtue of his ground shaking birth and the fortune of being rediscovered by a caring patron of music history years after his death. Indeed, there’s more to Vivaldi’s life than simply his most recognized violin and orchestral compositions. The following Vivaldi facts and trivia have been gleaned from various historical biographies and similar sources.

On the day of his birth, March 4, 1678, a large earthquake occurred in Venice.

Young Antonio was taught to play the violin by his father, a professional violinist who was also a barber. Father and son toured Venice playing violin together.

At age 15, he began studies to become a priest and was nicknamed Il prêt Rosso, or The Red Priest. It is speculated that this was due to his red hair, which was a family trait.

Vivaldi suffered from a form of asthma which limited his duties administering Mass but gave him more time to spend writing music.

He produced many of his major works while employed for approximately 30 years as a master violinist at the Ospedale della Pieta, a home for abandoned children. The boys were taught a trade. The female orphans received expert musical instruction and became members of the choir and orchestra. Their performances were well respected all around the region.

His famous set of 4 violin concertos, The Four Seasons, (1723) is considered to be an outstanding example of program music. Each concerto depicts a scene appropriate for each season and is accompanied by a written description.

J.S. Bach was a huge fan of Vivaldi’s music. He transcribed several of Vivaldi’s concerti for keyboard, strings, organ and harpsichord.

The musical compositions of Vivaldi total 500 concertos, 90 sonatas, 46 operas and a large body of sacred choral works and chamber music.

Vivaldi was commissioned to create music for European nobility and royalty. The well recognized Cantata; Gloria, was written for the celebration of the marriage of Louis XV in 1725. Additional pieces were written for the birth of the French royal princesses and Vivaldi was given the title of knight from Emperor Charles VI of Vienna.

Vivaldi relocated to Vienna at the invitation of Charles VI who died shortly after, leaving Vivaldi with no one to support him. However, because his music had not kept up with the times, he was forced to sell off his compositions in order to live.

Unfortunately, Vivaldi died a pauper and was given a simple burial. The master musician was not even afforded music at his own funeral, only the peeling of bells at St. Stephen’s Cathedral noted his passing.

Interestingly, the young composer Joseph Haydn, employed at the cathedral, had nothing to do with this burial since no music was performed.

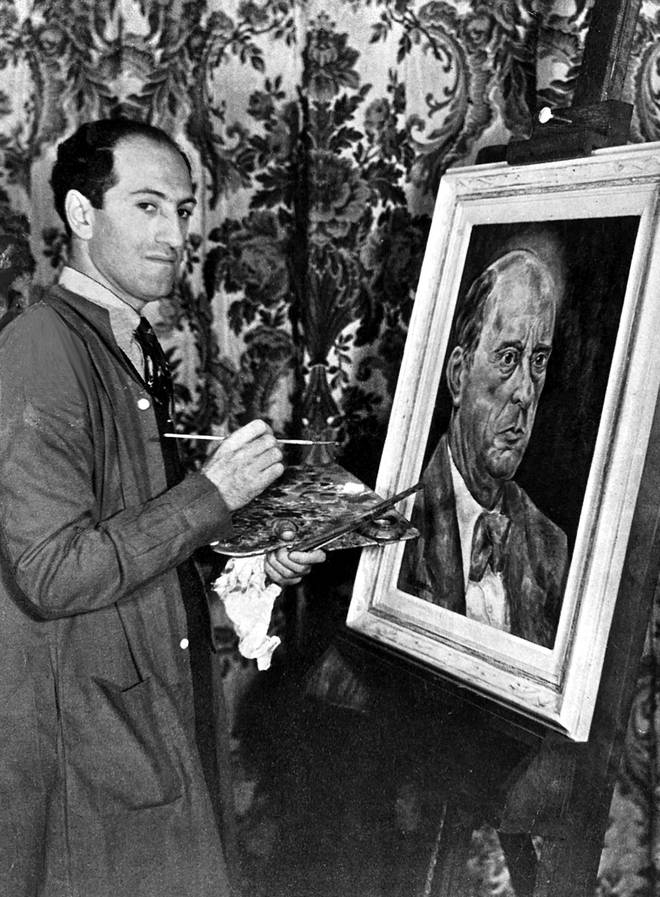

His complete catalogue of music was not fully realized until 1926. A large collection of manuscripts were discovered in a boarding school in the Piedmont, diligently researched and procured by Dr. Alberto Gentili, a music historian at the University of Turin.

World War II stopped the momentum of the Vivaldi renaissance with burned out warehouses and printing presses. Little by little, though, newly discovered Vivaldi items began to appear and spread across Europe.

By 1951, London hosted the great postwar Festival of Britain presenting a concert season devoted mostly to the baroque master and firmly secured his place in music history.

2006 was the most recent discovery of a lost piece, Vivaldi’s opera, Argippo, which had last been performed in 1730.

His life and times have been documented in a 2005 movie, Vivaldi, A Prince in Venice, and a radio play for ABC Radio that same year. It was later adapted into a stage play entitled The Angel and the Red Priest.

Vivaldi was an innovator in Baroque music and he was influential across Europe during his lifetime. As a composer, virtuoso violinist, pedagogue, and priest, his life and genius influenced a number of notable artists. However, because of struggles later in life, his music was nearly lost to obscurity. Thankfully, the meticulous efforts of diligent researchers have ensured that his great body of music will be available to inspire countless, future generations of musicians.

Check out these two examples of Vivaldi’s most celebrated compositions, Vivaldi Four Seasons performed by I Musici, in 1988, and Musica Intima & Pacific Baroque Orchestra performing Gloria.

Published by Revelle Team on May 24, 2016