By Emily F. Hogstad, Interlude

Salieri v. Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Antonio Salieri © slavicwritings.com

Everyone who saw the 1984 movie “Amadeus” knows the story. Antonio Salieri was a mediocre composer who was blindingly jealous of his young and impish colleague, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. In fury, he sabotages his career – and ultimately, his life.

That said… It’s not true. In real life, Salieri was a generally well-liked and well-regarded man, and a prolific and talented composer. He even taught Mozart’s son after Mozart died. And he didn’t poison Mozart.

The core of the legend came from letters that Mozart and his father wrote to each other in the 1780s, positing the existence of an “Italian cabal” that was seeking to block Mozart’s ascendance. The Mozart men were irritated that the Austrian court gave such prominence to the work of Italians; they believed that Austrian artists should reign supreme at court. This wider feud between Italian and Germanic styles of music persisted long after Mozart and Salieri, and perhaps consequentially, a rumor arose after their deaths that Salieri outright poisoned Mozart. So there was indeed a feud between the two composers, but it was a bit one-sided, and it wasn’t as dramatic – or deadly – as Hollywood suggests.

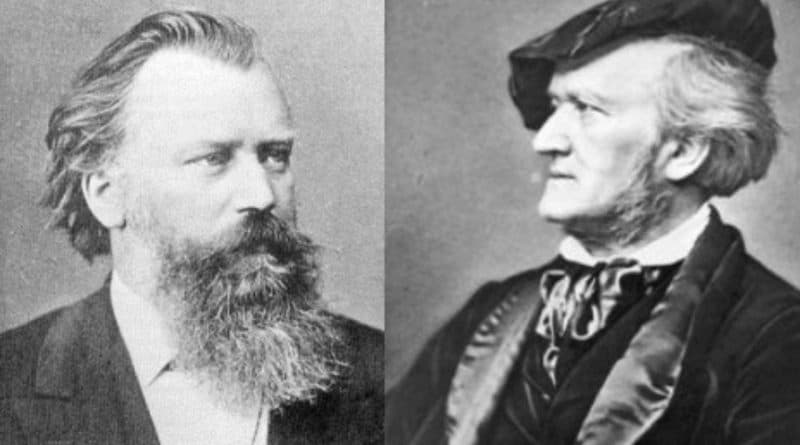

Brahms v. Wagner

Johannes Brahms and Richard Wagner © operalibera.net

After Beethoven’s revolutionary contributions to orchestral music, composers had to make tough decisions about how they would respond. Would they continue to embrace and refine the more instrumental-based genres that Beethoven had embraced, like the symphony or the sonata? Or would they throw out the old rule book and push forward to create new musical concepts and languages, as seen in program music? What genre would win the battle for cultural relevance: symphonies or operas?

This argument grew incredibly heated in the mid-1800s and became known (perhaps a bit melodramatically) as the War of the Romantics. Generally speaking, Johannes Brahms, Felix Mendelssohn, and Robert and Clara Schumann were seen as the “conservatives” in this struggle, while figures like Liszt, Berlioz, and Wagner were seen as the “radicals.” A great deal of ink was spilled delineating the positions of the two camps. In the end, Wagner never wrote a symphony, and Brahms never wrote an opera.

Although their music was very different, Brahms appreciated at least some of Wagner’s music. “I’m the best of Wagnerians,” he told his friends in private. He even collected original Wagner manuscripts (much to Wagner’s irritation). That said, Brahms wasn’t such a fan of the loud extra-musical opinions that Wagner blared in various screeds and pamphlets.

Debussy v. Ravel

Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel © wfmt.com

The music of Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel is often jammed together on compilation discs with titles like “French Impressionism.” But just because the two men were writing music at the same time in the same city doesn’t mean they were best friends.

They met around 1900 when Debussy’s stepson Raoul Bardac, a classmate of Ravel’s, introduced them. Ravel was thirteen years younger and at a different stage of artistic and professional development than Debussy was, and Ravel admired the older man’s work intensely, to the point where he was criticized in the press for copying Debussy too closely.

In 1903, a hubbub arose when Debussy wrote a piece that seemed to be inspired by the Spanish-sounding strains in Ravel’s music. It was understandable for a younger man to copy an older one, the train of thought went, but should the older one be the composer copying the younger one? Then in 1913 the two – without knowing the other one was embarking on the same project – set some of Stéphane Mallarmé’s new poetry to music, before the poetry had been published. Their mutual distrust grew.

Another scandalous issue closer to home had caused the two composers to drift apart emotionally. Raoul Bardac introduced his (married) mother to (the married) Debussy…and the two fell in love and ran off together. Debussy’s first wife was left without a husband, and Ravel was one of the Parisians who made a financial contribution to her. The feud became official.

Mendelssohn v. Liszt

Franz Liszt and Felix Mendelssohn

We wrote an entire article about the rivalry between Felix Mendelssohn and Franz Liszt! But to make a long story short, these two men got caught up in the War of the Romantics, just like Brahms and Wagner did. On a more personal note, Liszt once rewrote portions of Mendelssohn’s G-minor piano concerto, which understandably greatly irritated Mendelssohn. They also had an encounter at a salon gathering that could easily have turned into a disaster, when Liszt debuted yet another arrangement that he’d made of one of Mendelssohn’s work, the Capriccio, Op. 5…but Mendelssohn managed to smooth it over by joking afterward and congratulating Liszt on his extraordinary performance.

Stravinsky v. Prokofiev

Sergei Prokofiev and Igor Stravinsky, 1920 © History of Music Facebook Page

Stravinsky and Prokofiev are often mentioned in the same sentence simply because they both were Russian composers, born in 1882 and 1891 respectively. But just like in the case of Ravel and Debussy, that didn’t guarantee they got along.

Although Stravinsky once magnanimously praised Prokofiev’s ballet “Chout” as “the single piece of modern music [he] could listen to with pleasure”, the relationship eventually deteriorated. By the following year, when “Chout” was being run through for a possible revival, Stravinsky started an argument with Prokofiev, telling him he was wasting his time writing opera. The younger man retorted that Stravinsky “was in no position to lay down a general artistic direction” since Stravinsky himself “was not immune to error.”

Prokofiev later described what came next: Stravinsky “became incandescent with rage” and “we almost came to blows and were separated only with difficulty.”