Johannes Brahms was seemingly nonchalant when it came to critical assessments of his work or the opinions of his fellow composers. Nevertheless, he proudly and secretly kept a handwritten list of works dedicated to him by other composers. In a small notebook, he compiled a list of 78 musical entries, plays, 4 books and 1 collection of prints. “In his own extensive library, Brahms had copies of most of these works, no doubt sent to him by the authors.” Additional titles were added to his memory shortly after his death. We thought it might be fun to initially explore 10 works dedicated to Brahms.

Robert Schumann: Introduction and Concert Allegro, Op. 134

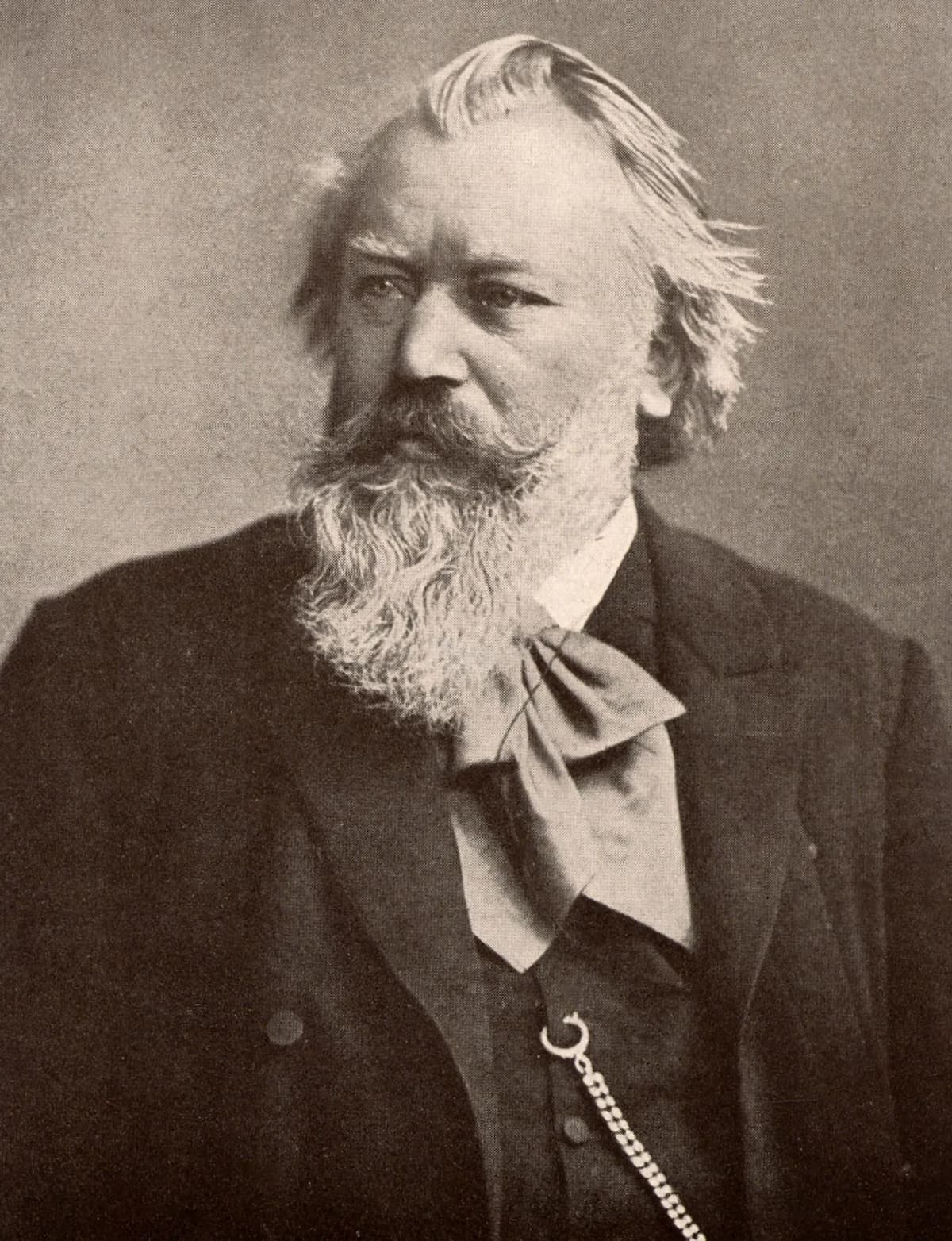

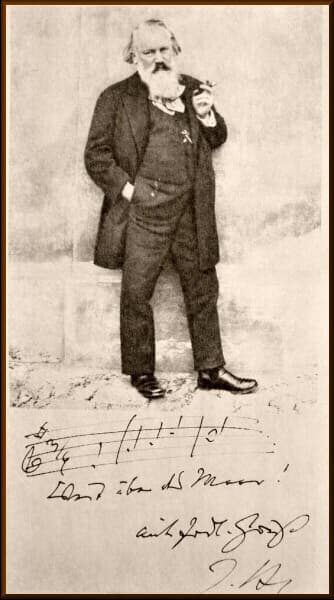

Johannes Brahms

Let’s start with Robert Schumann’s last work for piano and orchestra, the Concert-Allegro with Introduction, Op. 134. In April 1853, Brahms and the Hungarian violinist Eduard Reményi went on tour, and in Weimar, Joseph Joachim introduced him to Liszt and recommended a visit to Robert and Clara Schumann in Düsseldorf. Around that time, Schumann was working on a work intended as a thirteenth-anniversary present for his wife Clara, but he was so impressed by his young visitor that he dedicated it to Brahms instead.

Joseph Joachim: Violin Concerto in D minor, Op. 11 “In the Hungarian Style”

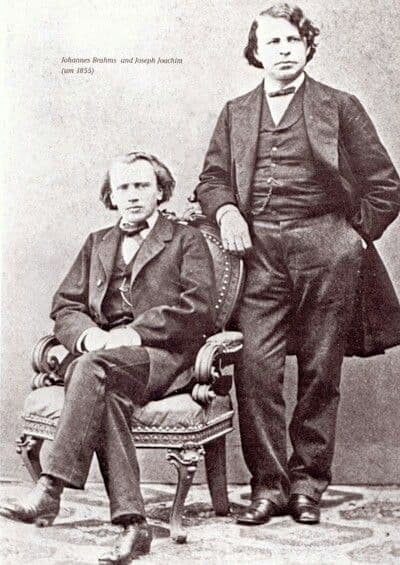

Brahms and Joachim, ca 1855

Talking about Joseph Joachim, we know that the Brahms Violin Concerto was exclusively written for and with the famous violinist. Since Brahms was not a violinist, he sent sketches of the solo part to Joachim for advice. He writes, “I wanted you to correct, and I didn’t want you to have any excuse of any kind; either that the music is too good or that the whole score isn’t worth the trouble. But I shall be satisfied if you just write me a word or two and perhaps write a word here and there in the music, like ‘difficult,’ ‘awkward,’ ‘impossible,’ etc.” Joachim worked painstakingly through the entire manuscript and communicated his suggestions to Brahms, who characteristically ignored most of it. It is probably less well known that Joachim, almost two decades earlier, had dedicated his “Hungarian Concerto” to Brahms.

The Violin Concerto in D minor enjoyed great popularity during Joachim’s lifetime, and like Liszt, Joachim was Hungarian by birth. “Joachim spoke little Hungarian, and he regarded the whole of Magyar culture with a wistful, romantic gaze.” Brahms in turn, had always found inspiration in Hungarian folk music, and he was suitably stimulated by the nostalgic melancholy and passionate abandon native to the “Hungarian Style.”

Clara Schumann: 3 Romances, Op. 21

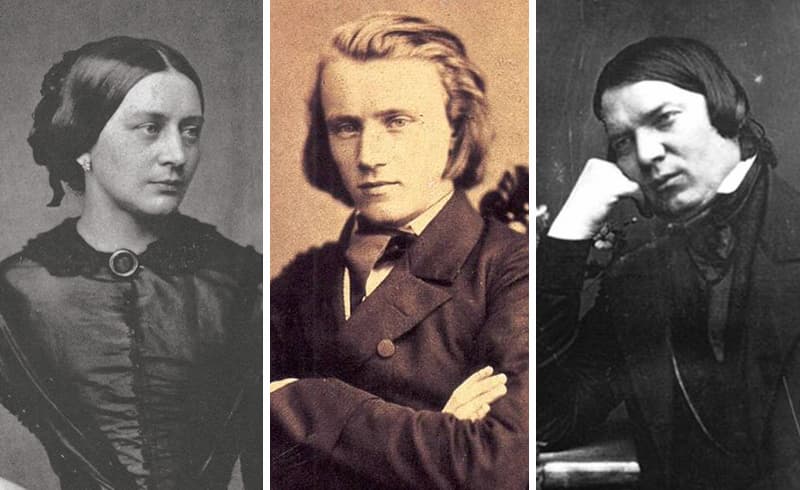

Brahms and the Schumanns

Clara Schumann dedicated the set of Romances, Op. 21 to Johannes Brahms. In late June 1853, Clara wrote three Romances in A minor, F Major, and G minor. However, in the published version, Clara substituted the original A-minor Romance with a Romance in the same key in 1855. The reason for the substitution was a visit of Johannes Brahms to Robert Schumann at the Endenich sanatorium. As she notes in her diary, “on that day the piece I composed is really sad in mood, just as I was when writing it.” This replacement Romance—the original was published separately in 1853—exists in two different versions and autograph sources. The first is dedicated to Johannes Brahms: “Composed for my dear friend Johannes, April 2, 1855,” and the other is dedicated to Robert Schumann: “For my beloved husband, June 8, 1855.” These two dedications are not contradictory, as they clearly reference the two men in her life at that particular time. Her emotional balancing act is reflected in the Three Romances, as she balances Classical formal structures with Romantic harmonies. “The pieces conform to Schumann’s society’s expectations of genre, melody, and form in a piece written by a woman. Its harmonic language meets the expectations of her Romantic peers, yet maintains the sense of restraint found in its form and lack of virtuosic show.”

Theodor Kirchner: Waltzes, Op. 23, No. 2-4

Theodor Kirchner

As we are talking about romances, maybe we should turn to Theodor Kirchner next. He was a capable pianist, organist, and composer, and according to some biographers, “Clara decide to take Kirchner as her lover in 1857 because he was unassertive in character and would appear only when she needed him, and that the affair then continued uninterruptedly for eight years.” That particular narrative seems to have been discredited, but we might suggest with some degree of confidence that their relationship included some sexual intimacy, if only for a short period of time. Kirchner does appear in Clara’s diaries, but “she considered that he had lacked fiber, both as a man and as an artist, and that she was in fact to make several efforts over the next few years to instill some in him.” As she writes, “Pull yourself together, dear Kirchner, you are still a man in full possession of your mental and physical powers.” In 1863, she did call him “my beloved, and expressed feelings of profound love for him.” Within a year, however, the affair had run its course, and Clara told Brahms to never “bring that scoundrel Kirchner to her house again.” Brahms seems not to have been aware of the romantic relationship, and in typical fashion, he did not break his contact with Kirchner. On the contrary, he actively made sure that their relationship was getting closer. Kirchner, in turn, greatly admired Brahms’s music and dedicated his set of waltzes Op. 23 to him.

Johann Strauss, Jr. “Seid umschlungen Millionen,” Op. 443

Fritz Luckhardt: Johann Strauss II

When it came to waltzes, Johannes Brahms was a lifelong friend of Johann Strauss II, the “Waltz King” as he was commonly known. A contemporary reports “that Brahms used to play Strauss waltzes at his house with evident delight, sometimes for more than an hour.” He added, “Anyone who has heard Brahms play “An der schönen blauen Donau,” that most beautiful of all the waltzes composed by Strauss, will never forget the intense pleasure of the experience.” We are not sure when Brahms and Strauss met for the first time, but by 1872 Brahms told his friends that Strauss was one of the few colleagues for whom he felt total respect. By the mid 1890s, Strauss and Brahms spent their summers in Ischl, and their respective villas were close by. Brahms, it is reported, would become a regular guest at Sunday dinner, “and usually in a very jovial mood by the end of the meal, would, even without being asked, sit down at the piano and play Strauss waltzes and melodies from his operas.” On one such occasion, Brahms and Strauss are said to have played duets. Brahms marveled at the wealth of Strauss’ melodic invention and stated, “The man overflows with music.” Not to be outdone, Strauss dedicated his waltz “Seid umschlungen, Millionen!” (Be Embraced, Ye Millions!) Op. 443, to Brahms.

Julius Röntgen: Ballade on a Norwegian Folk Song, Op. 36

Julius Röntgen

The composer and pianist Julius Röntgen (1855-1932) did not immediately warm to the music of Brahms. They properly met in Leipzig in 1877 as Brahms was conducting his First Symphony. At a musical soiree at that time, Röntgen played Brahms chamber music in the presence of the composer. Brahms immediately took a great liking to him, but it was during Brahms’s visits to Holland that they got to know each other well. Röntgen played the Second Piano Concerto under Brahms’ direction, and the pianist started to feel increasing admiration for both the man and his music. In fact, Röntgen became a fervent admirer of Brahms’ music. They continued to meet repeatedly, and while Röntgen’s attitude towards Brahms was “solely one of passive reverence,” Brahms expressed his feelings with unusual warmth. As he writes to Clara, “Röntgen is a quite exceptional and most lovable man. He has remained a child, so innocent, pure, frank, and enthusiastic. Not for a long time have I taken such great pleasure in anyone.” Brahms even thought favorably of Röntgen’s compositions, characterising his talents as “light and pleasing.” In return, Röntgen dedicated his 1892 Ballad on a Norwegian Folk Song, Op. 36 to Brahms.

Ferruccio Busoni: Six Études, Op. 16

Ferruccio Busoni

Ferruccio Busoni arrived in Vienna for a two-year stay in 1883. He later remembered that he visited Brahms frequently and, on at least one occasion, showed him compositions that he intended to dedicate to him. We have no information regarding Brahms’ reaction, but since they were rather youthful compositions, it seems that Brahms advised Busoni to study composition and counterpoint with Gustav Nottebohm. Busoni hated his lessons with Nottebohm and quickly discontinued being his student, upon which Brahms supposedly remarked “I have largely ceased contact with Busoni, since I don’t care for children who consider themselves infant prodigies.” Nevertheless, Brahms did subsequently furnish Busoni with a letter of recommendation for study in Leipzig and supposedly remarked “that he would do for Busoni what Schumann did for me.” In the event, Busoni did dedicate his Six Études, Op. 16, to Brahms in 1884, and the stylistic indebtedness is immediately apparent.

Max Reger: 6 Pieces for Piano, Op. 24, No. 6 “Rhapsody to the memory of Johannes Brahms”

Max Reger

Max Reger and Johannes Brahms never met, but in late 1894, Reger referred to Brahms as “the greatest of living composers.” As he writes, “Brahms is nonetheless now so advanced that all truly insightful, good musicians, unless they want to make fools of themselves, must acknowledge him as the greatest of living composers… The Brahms fog will remain. And I much prefer it to the white heat of Wagner and Strauss.” Reger considered Brahms an innovator who used classical forms with amazing freedom of thought, an idea later further developed by Arnold Schoenberg who writes, “Brahms the classicist, the academician, was a great innovator in the realm of musical language, and in fact a great progressive.” Reger had studied at the Conservatory in Wiesbaden under Hugo Riemann, and he began to “adopt Brahms’s technique as a tool for expressing what moved him. Reger absorbed so much of Brahms’ expression and spirit, in part, the ability to get a clear sense of the individuality of his own works.” Reger and Brahms might not have met, but they did exchange a number of letters. In April 1896, Reger sent his Organ Suite to Brahms for approval, and he enclosed a planned Symphony in B minor with a letter asking for permission to dedicate the piece to Brahms. Brahms responded, “I have to thank you most heartily for your letter, whose warm and most friendly words I found exceedingly pleasant. In addition, you are considering rewarding me with the beautiful present of a dedication. My permission for this is really not necessary! I had to smile because you asked me for that while including a work whose all too bold dedication frightens me! Therefore, you may certainly go ahead and add the name of your respectfully humble J. Brahms.” In the end, the symphonic dedication did not materialize, but the “Rhapsody to the memory of Johannes Brahms” appeared around the first anniversary of Brahms’ death.

Josef Suk: Piano Quintet in G minor, Op. 8

Josef Suk

Josef Suk (1874-1935) was Antonín Dvořák’s son-in-law, and he was a member of the “Czech Quartet”, including Karel Hoffmann, Oskar Nedbal, and Otto Berger. They made their highly successful Viennese debut in 1893 and rose to become one of the leading chamber music ensembles in Europe. In fact, they performed until 1933, when Suk retired. Suk remembered that he called on Johannes Brahms during his time in Vienna in 1893 to thank him for the recommendation that had resulted in a state scholarship for composition. Apparently, he was received with Brahms’ “typical mixture of kindness and gruffness.” Brahms asked him, “So you are the scholarship holder Suk? Let me tell you something: Next time, your composition must be more competent, or you won’t get anything.” Brahms also recommended Suk’s Serenade for Strings, Op. 6 to the publisher Fritz Simrock, and in return, Suk dedicated his Piano Quintet Op. 8 to Brahms.

Antonín Dvořák: String Quartet in D minor, Op. 34

Photograph of Johannes Brahms with greeting to Dvořák

Antonín Dvořák won the Austrian State Prize fellowship prize three times in 4 years. At the head of the selection committee were none other but Johannes Brahms and the fierce Viennese critic Eduard Hanslick. What impressed Brahms about Dvořák was “the seemingly unlimited inventiveness of his melodic materials, his uncanny sense of time and duration, and the dazzling sense of musical line.” A scholar writes, “Brahms’s enthusiasm for Dvořák was rooted in his recognition that he was a composer of such tremendous capacity that he possessed more than the ability to write novel tunes; Dvořák could, in fact, write extended musical essays of the quality to which Brahms himself aspired—modern incarnations of classical models.” Shortly before Dvořák’s third success in 1877, he received a letter from Brahms referring the young composer to his own publisher Fritz Simrock. In a gesture of gratitude, Dvořák pledged to dedicate his Quartet in D minor to Brahms. Brahms, who considered string quartets to be one of the most difficult forms of composition, recommended that Dvořák take a careful look over the score. Dvořák wrote in 1879, “During your last visit to Prague, you very kindly pointed out several places in my compositions, and I must now express my gratitude to you for so doing since I have now seen a great many bad notes, which I have replaced with better ones. I found it necessary to change numerous things in the Quartet in D minor, since you kindly agreed to allow me to dedicate the work to you; it was therefore my solemn duty to dedicate to so famous a maestro a work which fulfills, if not all, at least (please excuse my immodesty) many of the main conditions we may impose upon a work of music.”