It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Monday, October 31, 2022

Unforgettable

André Rieu - Nearer, My God, to Thee (live in Amsterdam)

Dionne Warwick - That's What Friends Are For

Dionne Warwick - That's What Friends Are For

Begin the Beguine (Remastered)

Sunday, October 30, 2022

Pink Floyd - Shine On You Crazy Diamond 1990 Live Video

Friday, October 28, 2022

Who Got It Right and Who Got It Wrong? Critics and Composers

by Maureen Buja

Here, John Gregory, writing in 1766 in his A Comparative View of the State and Faculties of Man with Those of the Animal World, had this to say about what composer?

‘[The style of COMPOSER] sometimes pleases by its spirit and a wild luxuriancy … but possesses too little of the elegance and pathetic expression of music to remain long in the public taste.’

Hmmm. So we want a mid-18th century composer who had spirit and a sense of luxury but lacked elegance…. Mozart? Hummel? No, they’re too late. Gregory was referring to the style of the music of Haydn, who, of all composers of his era, has remained in the public taste where so many of his contemporaries have vanished.

Hardy: Joseph Haydn, 1791

We have two composers with two very different views of conductors. The first, a composer, suffered poor performances in the hands of bad conductors:

‘Conducting is a black art.’

The other, a conductor himself, downplayed the difficulties in a letter to his 10-year-old sister:

‘It’s easy. All you have to do is wiggle a stick.’

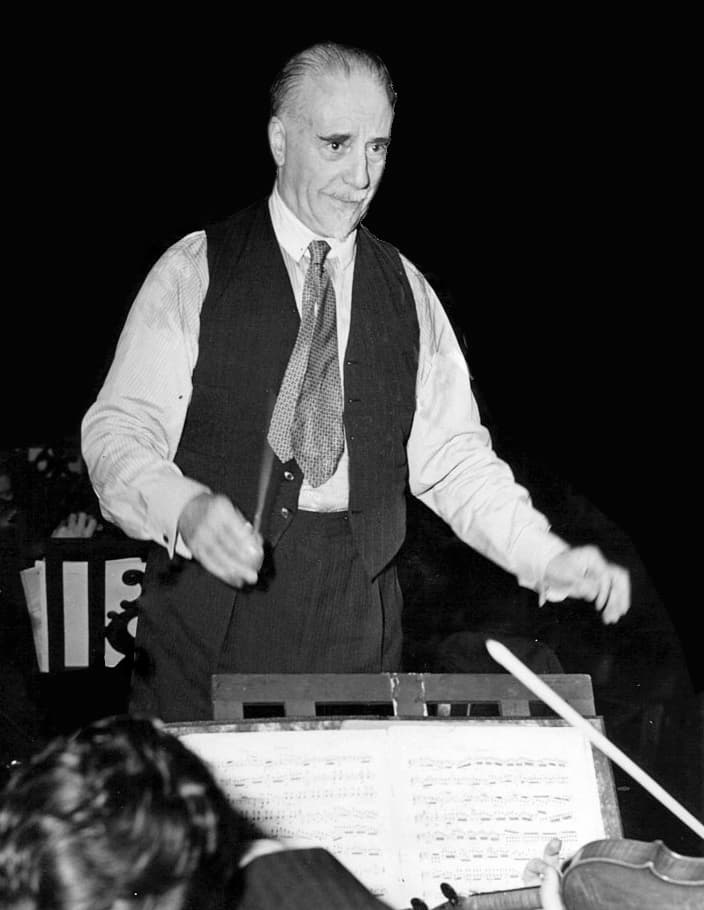

It was Tchaikovsky who held the first opinion, given in 1909, and Sir Thomas Beecham in the second quote.

Reutlinger: P.I. Tchaikovsky, c. 1888

Sir Thomas Beecham, 1948

Richard Strauss, on the other hand, felt that certain sections of the orchestra needed to be quelled at all times:

‘Never let the horns and woodwinds out of your sight. If you can hear them at all, they are too loud.’

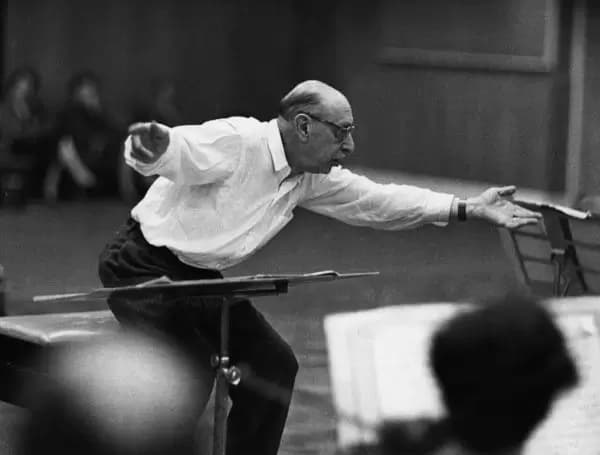

Igor Stravinsky , himself a composer and a conductor, saw danger in the field of conducting:

‘”Great” conductors, like “great” actors, soon become unable to play anything but themselves.’

and

‘Conducting is semaphoring, after all.’

Richard Strauss conducting

Stravinsky conducting

He also viewed conductors as the ‘lapdogs’ of musical life…which poses an interesting question of which side of Stravinsky was making that statement!

Very few composers or performers had anything good to say about critics.

Richard Wagner thought that ‘the immoral profession of musical criticism must be abolished,’ whereas Beecham saw the problem as one of lack of musical feeling, saying ‘…so often they have the score in their hands and not in their heads.’

Aaron Copland thought that ‘if a literary many puts together two words about music, one of them will be wrong’.

And the critics strike back:

George Bernard Shaw, when accused of being too critical: ‘No doubt I was unjust; who am I that I should be just?’

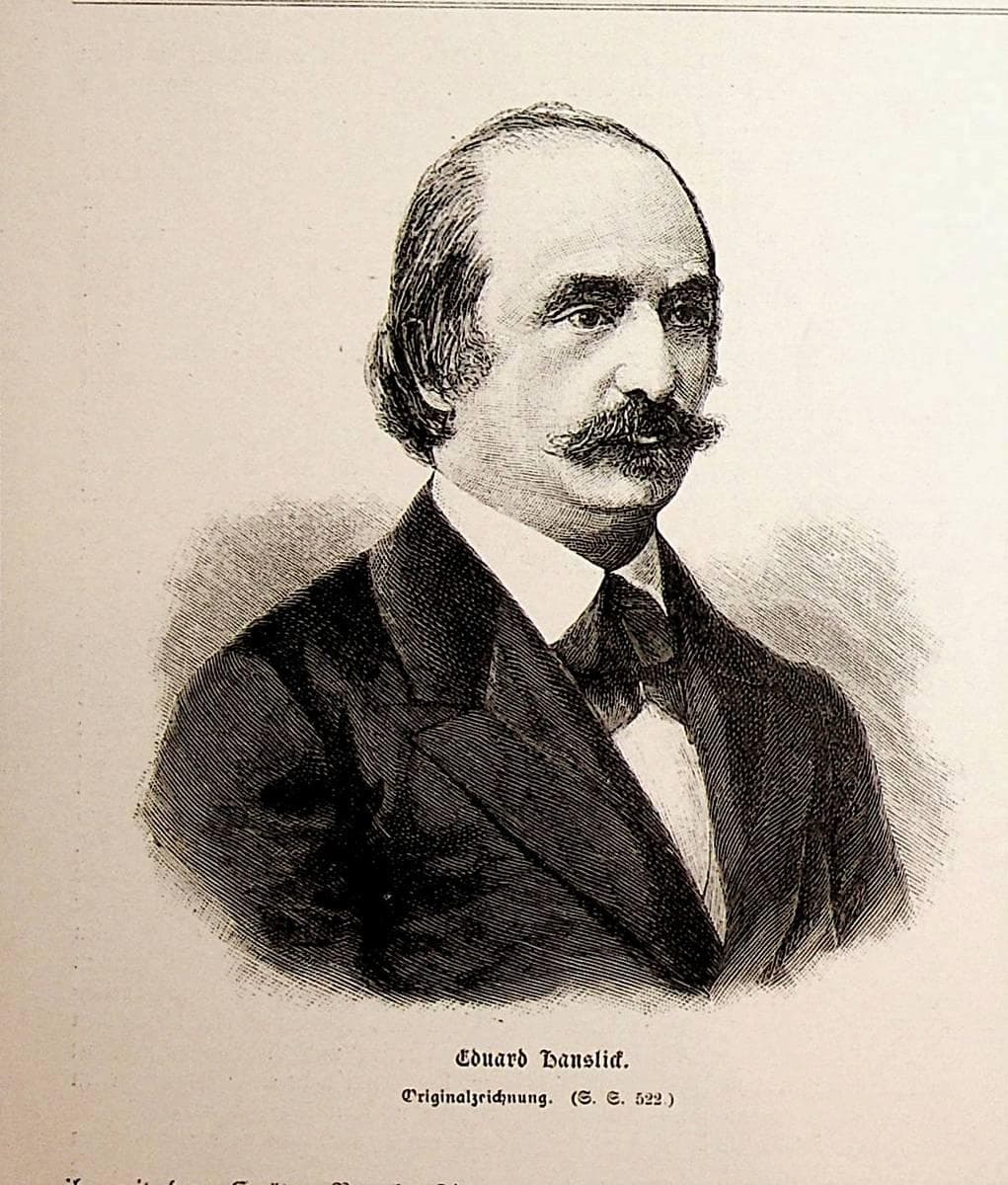

Eduard Hanslick, who wielded great power as critic, took an uncritical view of himself: ‘When I wish to annihilate, then I do annihilate.’

Eduard Hanslick

Oscar Wilde found Chopin to be too emotional: ‘After playing Chopin, I feel as if I had been weeping over sins that I had never committed, and mourning over tragedies that were not my own.’

Sometimes composers are most caustic about their contemporaries. Wagner wondered this about the legacy of Rossini: ‘After Rossini dies, who will there be to promote his music?’

Stravinsky pondered about South American music: ‘Why is it that whenever I hear a piece of music I don’t like, it’s always by Villa-Lobos?’

Some composers write about what they are proudest of. Modest Mussorgsky, known for his songs as much as his symphonic music and opera, said in a letter in 1868 ‘my music must be an artistic reproduction of human speech in all its finest shades’.

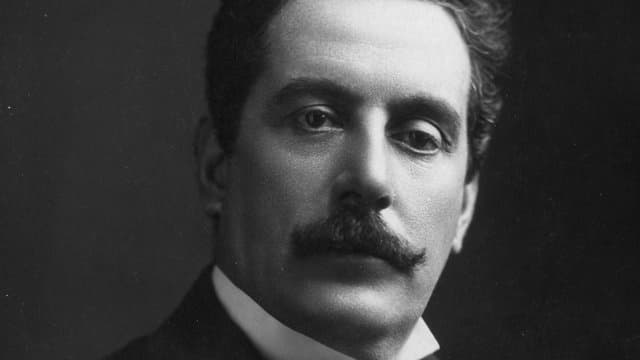

Puccini, understating his talents simply said ‘God touched me with His little finger and said “Write for the theatre, only for the theatre.”’

Giacomo Puccini

Rossini, never one to understate his skill, remarked ‘Give me a laundry-list and I’ll set it to music.’

Stravinsky, who was often so far ahead of his contemporaries musically as to be in another world, said ‘Silence will save me from being wrong (and foolish), but it will also deprive me of the possibility of being right.’

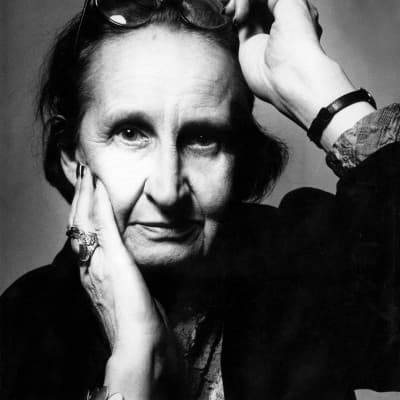

Elisabeth Luytens, who parlayed her contemporary sound into really effective music for British horror films, called her own style ‘eerie weirdness’.

Elizabeth Lutyens

Opinions, opinions … everyone has opinions. Some of them can make us ponder (‘Wagner has lovely moments but awful quarters of an hour’ – Rossini), others make us laugh (‘Hell is full of musical amateurs’ – George Bernard Shaw), and others make us angry (‘There are two kinds of music: German music and bad music.’ – H.L. Mencken) – what’s your opinion?

Thursday, October 27, 2022

Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 5 "Emperor" Op. 73 - Daniele & Maurizio Po...

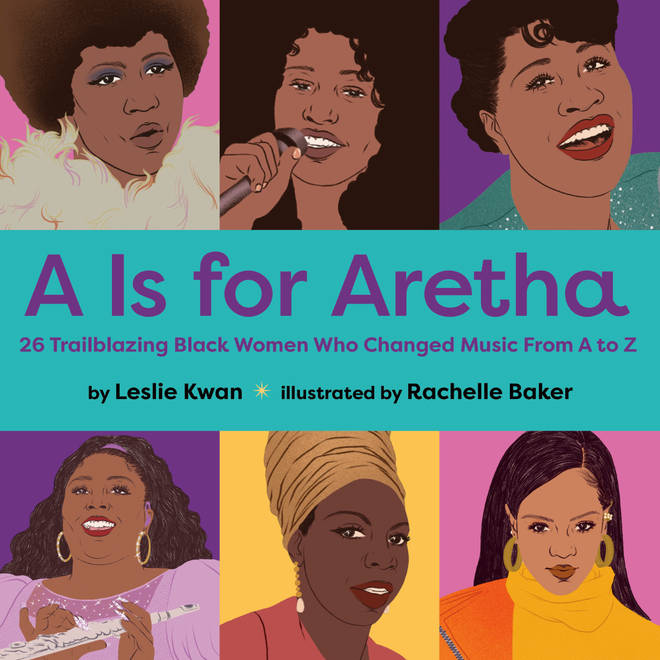

‘They would put white musicians on the cover’ – author spotlights music history’s trailblazing Black women

By Sophia Alexandra Hall, ClassicFM

@sophiassocialsWe speak to first-time author, harpsichordist Leslie Kwan, for Black History Month to learn more about some of history’s trailblazing Black women musicians – all featured in her new children’s book, ‘A is for Aretha’.

“I wanted to create a primer for teaching children about the Black women that created and shaped various genres of music,” author and harpsichordist Leslie Kwan tells Classic FM about her upcoming children’s book A is for Aretha, which spotlights 26 trailblazing Black women throughout the history of modern music – from Aretha Franklin and Lizzo, to classically trained musicians who faced barriers when entering the industry.

So many of these women, Kwan adds, were also “part and parcel to the shaping of civil rights, which was often commemorated in their songs”.

One of the musicians featured in her book is Odetta Holmes – known as Odetta. Now remembered as an American folk singer who played the guitar, growing up, Odetta and her peers believed she was destined for the stage of New York’s esteemed Metropolitan Opera.

In an interview with The New York Times during her lifetime, Odetta revealed that as a child, “a teacher told my mother that I had a voice, that maybe I should study, but I myself didn’t have anything to measure it by.”

Her mother reportedly wanted Odetta to be the next Marian Anderson, a Black contralto who would become the first African American singer to perform at the Metropolitan Opera in 1955. Odetta had a remarkably impressive vocal range, extending from a baritone to a soprano’s (G2 - B5).

Read more: 11 Black opera singers you should know about

Odetta began operatic training at the age of 13, however admitted later in life that she was always pessimistic about her chances of making it in the world of classical music.

The folk musician told the Albany Union Times towards the end of her life that, “I was a smart kid and I knew that a black girl who was big like I was was never going to be in the Metropolitan Opera.

“Look at Marian Anderson, my hero. It wasn’t until she was almost retired before they invited her to sing at the Met. I had taken the clues.”

Feeling shunned by the world of classical music, Odetta would go on to find her voice in folk music, and became an integral figure in the American folk music revival of the 1950s and 1960s.

She was often referred to as ‘The Voice of the Civil Rights Movement’, for her music which expressed the experiences of racism and injustice faced by Black people. Rosa Parks was reportedly ‘her No. 1 fan’, and in 1961, Martin Luther King Jr. dubbed her the ‘Queen of American folk music’.

Then, there was Nina Simone. Simone, who at the time still went by her birth name Eunice Waymon, enrolled in New York’s Juilliard School during the summer of 1950, and later applied for a scholarship to study at Philadelphia’s Curtis Institute.

She was denied admission despite a great audition, and throughout her life, Simone recounted that this rejection had been due to her being profiled because of her race.

Simone’s family had moved to Philadelphia due to their expectation that the young pianist would be accepted, which made the rejection extra painful for the aspiring classical musician.

In the documentary What happened, Miss Simone?, the world-renowned singer and pianist recalls of her audition, “I knew I was good enough, but they turned me down. And it took me about six months to realise it was because I was Black. I never really got over that jolt of racism at the time.”

Discouraged by the failed audition, Simone began taking private lessons with Curtis Institute piano professor, Vladimir Sokoloff. To fund her lessons, she began performing at New Jersey’s Midtown Bar & Grill, where she would play piano and sing under the stage name, Nina Simone.

This career move would change the direction of her life forever, and the events that followed this posting led to her becoming the legendary American singer, songwriter, pianist, and civil rights activist she is remembered for being today.

Read more: 19 black musicians who have shaped the classical music world

‘They would put white musicians on the cover of Black musicians’ recordings’

As a pianist by training, Kwan was particularly excited to feature Simone in her upcoming book.

“Nina Simone, she spent time in Paris like me, so I felt like I had a particular connection to her. We had similar experiences, especially as pianists, and I understood the story of her conservatoire experience.”

Kwan, who is first generation Guyanese-American, raised in Long Island, cites American actress Viola Davis, who recently spoke out about the difficulties getting her new film Woman King made.

“Davis had to fight to get the Woman King made, because the bottom line in Hollywood is money. Because films with a predominately Black female cast haven’t led the global box office, there’s no precedent that it will work.”

“It was the same in the music industry, particularly during the 20th century. Thinking about popular music in the 20th century, labels would hire Black musicians to sing and do recordings, but then would not put those musician’s faces on the recordings.

“Instead they would put white musicians on the cover, as recordings with Black musicians on the cover ‘wouldn’t sell as well’.”

Similarly, history reveals a multitude of examples of white musicians being asked to cover songs that were intended for and originally recorded by Black musicians. ‘Hound Dog’ was a song made famous in mainstream music by Elvis Presley, but it was originally recorded by Big Mama Thornton. Thornton’s original track sold almost two million copies in 1953, from which she earned a total of just $500.

Kwan is passionate about platforming these Black women musicians – showcasing who they were, what they did, and why it’s important to know about them.

Through her children’s book, she hopes the musicians featured won’t remain the ‘Hidden Figures’ she worries they have in some instances become. It was an interaction with her niece that ultimately inspired the title.

After singing Franklin’s 1967 hit, ‘Respect’ in front of her young relative, Kwan pondered why there weren’t “any books talking about Black women musicians” specifically aimed at children. This led to her writing A is for Aretha shortly after.

“Black women in music have been reduced to Hidden Figures – and I don’t want that,” she says.

A talented musician, Kwan began her piano studies at age 4 and made her debut at Carnegie Recital Hall at age 10. Kwan went on to receive a BA in harpsichord performance from Hofstra University in Hempstead, NY, and a Master of Music from the Mannes College of Music, New York City where she was a Helena Rubenstein scholar.

Subsequently, the Harpsichordist understandably defines herself as a ‘musician’ above all else. On why she therefore decided to turn her most recent career venture to writing, Kwan quotes American novelist Toni Morrison.

“If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.”