by Georg Predota

From piano practice to impromptu songs, Jane Austen’s world is full of musical moments that tell us about character, class, gender and even politics. Recent scholarship has deepened our appreciation of how Austen, an active amateur musician herself, used music as both a domestic texture and a narrative instrument.

Jane Austen

To celebrate her 250th birthday on 16 December 1775, let’s explore how Jane Austen (1775-1817) was not merely a spectator but a participant in musical life.

Sounding the Social World

Jane Austen’s engagement with classical music was both cultivated and personal, reflecting the social and cultural milieu of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Music played an essential role in her daily life, both as a form of polite entertainment and as a vehicle for emotional expression, a theme that recurs in her novels.

Music was indeed central to her daily routine. The pianoforte was the primary instrument in her circle for domestic music-making. Austen owned or had access to pianofortes like the Clementi square piano, similar to one at her Chawton home, and keyboard pieces dominated amateur performances in drawing rooms.

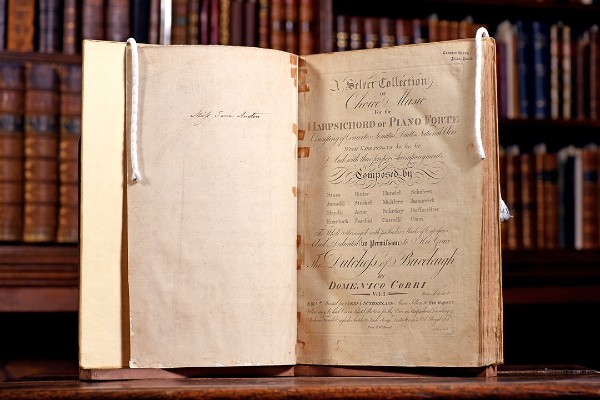

She practised the pianoforte most mornings before breakfast for personal enjoyment, often copying sheet music by hand. Her family’s collection of roughly 600 pieces includes works by Mozart, Haydn, and Clementi.

From Pleyel to Dibdin

Jane Austen’s music book

Mozart overtures, Haydn adaptations, and Clementi sonatas provided a common repertoire for the evening of performance. Her favourites leaned toward contemporaries like Ignaz Pleyel, Johann Baptist Cramer, and the English theatrical composers like Dibdin and Shield. Her collection emphasised popular songs, Scottish/Irish airs, and lighter keyboard works.

These domestic music books and family collections have given scholars fresh material to link Austen’s actual repertoire with the musical references that appear in her fiction. Knowing Austen’s own musical habits makes it easier to read her fictional music as informed, sometimes affectionate, sometimes satirical commentary.

Scholars have pointed out that juvenile songs Austen enjoyed in her teens show multiple registers, including sentimentality, comic satire, and even political protest, tonalities that wryly surface again in her novels.

Ambition and Accomplishment

Jane Austen by Cassandra Austen

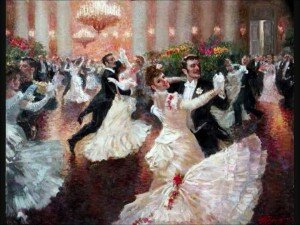

In Austen’s time, music was primarily a domestic art. A genteel young woman of accomplishment was expected to sing and play the pianoforte at home. Austen’s novels stage precisely these private performances.

Lucy Steele sharing a song in Sense and Sensibility; Marianne Dashwood’s pianoforte playing in Sense and Sensibility; the piano-less Fanny Price in Mansfield Park is conspicuously sidelined for social reasons.

Such moments are rarely mere background. How a character performs, what they choose to play, and who listens to all work as shorthand for taste, education, ambition and moral temperament. Recent work on class and music in Austen shows how musical accomplishment maps onto social aspiration and mobility in subtle, often ironic ways.

Gendered Expectations

Austen’s musical scenes are often gendered in telling ways. Women perform and are judged for their musical accomplishments, while men more often appear as listeners, critics, or, in some cases, as amateur players.

Scholars working at the intersection of musicology and gender studies have recently explored how Austen’s novels stage the female musical body. The nervousness of public performance, the social risk of attracting attention, and the way music can both empower and limit women in a society that prizes modest display.

New analyses argue that Austen’s attention to the embodied aspects of music, the posture at the pianoforte, voice quality, and the glance of a listener, is a realistic record of how musical behaviour operated as social grammar in the Georgian drawing room.

The Hidden Power of Music

Why should we pay attention to music in novels that are, at first glance, all about manners and marriage? Because music is a compressed language of feeling and status. Austen, who lived in a culture where a well-turned melody could signal breeding or bankruptcy of taste, used music to say what speech could not.

Reading Austen with an ear for music opens up new shades of irony and sympathy, helps explain character dynamics, and connects the fiction to the lived experience of Georgian households.

This was a world where the piano sat at the centre of private life, and where a song could be both comfort and provocation. Recent scholarship has encouraged us to hear Austen not merely as a novelist of manners but as a writer who understood the sonic textures of social life and used them with artful precision.