It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Sunday, June 2, 2024

Traumhafte Version von Claude Debussys "Claire de Lune"

"Philippine Classical Music"

"Philippine Classical Music" generally refers to 19th-20th century instrumental and vocal works by Filipinos made with the influence of Western music movements, notably of romanticism, post-romanticism, impressionism, and many others.

Among the major Philippine contemporary composers are Francisco Santiago, Nicanor Abelardo, Antonio Molina, Col. Antonino Buenaventura, Lucio San Pedro, Alfredo Buenaventura, and Ryan Cayabyab

Francisco Santiago Santiago (January 29, 1889 – September 28, 1947) was a Filipino musician, sometimes called The Father of Kundiman Art Song.

Life

Santiago was born in Santa Maria, Bulacan, Philippines, to musically minded peasant parents, Felipe Santiago and Maria Santiago. In 1908, his first composition, Purita, was dedicated to the first Carnival Queen, Pura Villanueva, who later married the distinguished scholar Teodoro Kalaw.

He studied at the University of the Philippines (UP) Conservatory of Music, in its original campus in Manila, obtaining a degree in Piano in 1921, and a degree in Science and Composition in 1922. He went to the United States to pursue further education. He first obtained his master's degree at the American Conservatory of Music in June 1923, and finally a Doctorate degree at the Chicago Musical School in August 1924. He is the first Filipino musician to attain a doctorate degree.

He became the director of the UP Conservatory of Music in 1930, after the entire music faculty and students of the conservatory protested for the removal of the previous director, Alexander Lippay, for alleged harassment of students and musicians. Santiago is the first Filipino director of the Conservatory.

In 1934, the President of the university, Jorge Bocobo, launched a committee to collect and document folk songs of the Philippines. Francisco Santiago was named the chair of the committee. Part of this committee were dancer Francisca Reyes-Aquino, who notated numerous folk dances and compiling them in several books, and composer Antonino Buenaventura, who transcribed numerous folk music, including those accompanying the dances recorded by Reyes-Aquino.

In 1937-1939 Santiago would compose his masterpiece - the "Taga-ilog" Symphony in D Major. It is one of the first Filipino classical works to feature Philippine instruments such as the gangsa and sulibaw.

Plagiarism case

In 1939 he was faced with a plagiarism lawsuit by another Filipino composer Jose Estella. According to Estella, Santiago stole a melody from Estella's 1929 work Campanadas de Gloria and incorporated it in Santiago's 1939 song Ano Kaya ang Kapalaran. However, the investigation found out that both Estella and Santiago's melodies were influenced by the folk song "Leron, Leron Sinta" and that Estella's Campanadas de Gloria also contained several quotations from other composers, therefore breaking Estella's claim. The court decided in favor of Santiago in 1942.[2]

War years[edit]

During the Japanese occupation of the Philippines the University of the Philippines was closed down by the invading Japanese forces. In 1942, Francisco Santiago became music director of the newly established New Philiippines Symphony Orchestra - created to replace the Manila Symphony Orchestra who refused to play under the Japanese rule. In 1943 he suffered a heart attack and his hand and arm were later paralyzed in an illness.

On February 5, 1945, during the Liberation of Manila, while the family was escaping their neighborhood due to constant bombing, a cart full of Santiago's compositions and manuscripts caught fire near the burning Quiapo Church. The family eventually escaped the shelling, but most of Santiago's compositions were destroyed.

Death

After the war in 1946, he was named Professor Emeritus by the University of the Philippines. He died one year later on September 28, 1947, and was buried in Manila North Cemetery.

Jose Estella (1870 - 6 April 1943) was a Filipino composer and conductor who was known for his title as the "Philippine Waltz King".[Besides composing waltzes, he also became one of the major contributors of localizing Spanish zarzuelas from 1890s to 1900

Jose Estella was born in Escolta, Manila in 1870. After studying and graduating from the Madrid Conservatory, he returned to the Philippines and pursued a career in music. In Manila and Cebu, he conducted several orchestras. In Manila, he had a teaching career as a piano instructor. He spends his time studying history, visiting different Filipino provinces and exploring the local folk music. In Cebu, he was director of the Municipal Band where he started to gain recognition.Estella also became a director of the Rizal Orchestra, founded in 1898.

Estella became involved with a plagiarism case in 1939 with Francisco Santiago over which he complains that Santiago copied his Campanadas de Gloria. In the end of the investigation, it was revealed that they both get inspiration from the same folk song named "Leron Leron Sinta".

He died on April 6, 1943, and throughout his lifetime, he composed more than 100 waltzes hence he is given the title, "the Philippine Waltz King". There are no information regarding his personal life except he has a son named Ramon Estella, a film director.

Notable works

Ang Maya

Composed in 1905, it was a piece from Estella's zarzuela, "Filipinas para los Filipinos" with Severino Reyes as librettist The piece represented the everyday life of the common people in the Philippines, thus predating some works by other composers who graduated from UP Conservatory of Music in the 1920s. Severino's youngest son, Pedrito, said that the song was inspired by the maya chirping in the trees near his father's summer hut. Estella's "Filipinas para los Filipinos" was a satire made by the composer as a reaction to an American Congress bill banning American women from marrying Filipino men.

La Tagala

Originally composed for piano in 1890s and 1900s, the waltz is a collection of Filipino folk songs such as Balitaw, Hele hele, Kundiman, Kumintang, etc. It was dedicated to the Tobacco Company Germinal. One of its notable performance was on a concert night of November 1899.

Filipinas Symphony (1928)

Jose Estella's Filipinas Symphony is the first Filipino Symphony by modern scholarly consensus.[2][8][11] Although not much was known about the information of the piece, according to sources, the symphony was based on the Filipino folk song "Balitaw" meanwhile the Slow Movement (Adagio) was based on another folk song "Kumintang".

Other Works

California March (Ragtime)

El Diablo Mundo - First performed at the inauguration of the Teatro Zorrila on October 25, 1893, this zarzuela was described to have a dark and gloomy atmosphere.

Los Pajaros[

Katubusan (Fox-Trot)

My Dreamed Waltz

Friday, May 31, 2024

Lullaby of Tears Claude Debussy: Berceuse héroïque

by Georg Predota , Interlude

The Battle of the Somme was fought between 1 July and 18 November 1916. One of the largest and most brutal engagements of the First World War, almost one million men were wounded or killed! Among them was the young British composer George Butterworth, who was shot through the head by a sniper in August 1916. Butterworth was one of thousands of well-educated soldiers that chronicled their personal experiences through words, art and music. The writers Robert Graves, JRR Tolkien and Edmund Blunden left a legacy of poetry, memoirs and fiction that helped future generations to understand the reality of war. The same is true for Ralph Vaughan Williams, Gustav Holst and Maurice Ravel.

The Battle of the Somme © dailymail.co.uk

Ravel had hoped to help his country as an aviator, but was considered too old and too short. As such, he served as a driver on the Verdun front, and he memorializes six of his dead friends in Le tombeau de Couperin. Arnold Schoenberg, entirely immersed into his reorganization of traditional tonality, was first drafted into the Austrian Army at age 42. He served for almost a year before a petition for his release was granted. One year later, he was called to active duty again, but given his advanced age, was assigned light duties in and around Vienna.

Claude Debussy © super-conductor.blogspot.com

Claude Debussy, meanwhile, was fighting his own personal battle against colon cancer. He dejectedly wrote, “My age and fitness allow me at most to guard a fence…but, if, to assure victory, they are absolutely in need of another face to be bashed in, I’ll offer mine without question.” Just a couple of years earlier, Debussy had hoped for a quick end to hostilities, but was eventually drawn into a well-organized propaganda campaign protesting the violation of Belgian neutrality by the Germans. King Albert’s Book: A Tribute to the Belgian King and People from Representative Men and Woman Throughout the Word was published in November 1914, and included contributions by Edward Elgar, Jack London, Edith Wharton, Maurice Maeterlinck, among numerous others. Debussy contributed the Berceuse héroïque, a short improvisatory piano piece full of melancholy and discretion that the composer explained “has no pretensions other than to offer an homage to so much patient suffering.”

As the war entered its second year, life for Debussy and his family became a real challenge. Shortages of food and fuel, and a steady escalation of cost made it increasingly difficult to earn a living. “It is almost impossible to work,” Debussy wrote, “to tell the truth, one hardly dares to, for the asides of the war are more distressing than one imagines. I am just a poor little atom crushed in this terrible cataclysm.” Yet, Debussy took heart and began to compose more than he had in years. These works, among them En Blanc et Noir for two pianos, Douze Études composed and dedicated to Chopin, the Sonata for flute, viola and harp and the Cello Sonata are strongly affected by the war. Debussy wrote to a friend, “these works were created not so much for myself, but to offer proof, small as it may be, that French thought will not be destroyed…I think of the youth of France, senselessly mowed down…What I am writing will be a secret homage to them.” The Sonata for violin and piano of 1916/17 was Debussy’s last completed composition, and below his name proudly appeared the telling signature “musicien français.”

Debussy’s last surviving musical autograph, a short piano piece, was presented as a form of payment to his coal-dealer, probably in February or March 1917. The bombardment of Paris as part of a final German offensive commenced on 23 March 1918, two days before Debussy’s death. By that time, the composer was too weak to be carried into the shelter. Yet his perception of war had fundamentally changed. “When will hate be exhausted?” he wrote, “or is it hate that is the issue in all this? When will the practice cease of entrusting the destiny of nations to people who see humanity as a way of furthering their careers?”

Recommended Recordings of Chopin Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor, Op. 11

by Ansons Yeung, Interlude

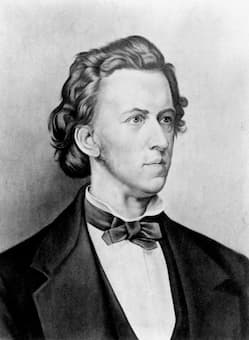

Frédéric Chopin, after a portrait by P. Schick, 1873

© Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

One of the greatest piano concertos ever, Chopin Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor has long been a cornerstone in the repertoire of many concert pianists. It was actually Chopin’s second piano concerto, as it was written after the premiere of Piano Concerto “No. 2” in F minor. Preceded by trials with a quartet and a small orchestra, the premiere took place in October 1830 at the National Theatre of Warsaw with great success. The concerto enjoyed immediate popularity and remained so up to this day.

As we appreciate this masterpiece, we should imagine ourselves as the 20-year-old Chopin deeply enchanted by his first love, Konstancja Gładkowska, who inspired both of his piano concertos. Chopin wrote to his friend Tytus Woyciechowski, “As I already have, perhaps unfortunately, my ideal, whom I faithfully serve, without having spoken to her for half a year already, of whom I dream, in remembrance of whom was created the Adagio of my Concerto” (referring to his Piano Concerto in F minor). Before Chopin left Warsaw, Gładkowska wrote the following poem in Chopin’s diary to bid him farewell:

Yet while others may

Better appraise and reward you,

They certainly cannot

Love you more strongly than we.

I. Allegro maestoso

Konstancja Gladkowska

The orchestra makes a majestic declaration, followed by the second theme in E major marked cantabile, but the music soon resumes its agitated mood. In fact, the indication maestoso often appears in Chopin’s music, such as in Polonaises Op. 26 No. 2, Op. 53 (“Heroic Polonaise”), Op. 71 No. 1, as well as the first movement of Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor. The piano part presents itself with a powerful, dignified first theme, while the second theme in E major conveys much warmth and intimacy. Later, the second theme appears again but this time in G major, creating a heartrending contrast with the ensuing section with spiralling anxiety and coda, ending in sudden unison in forte.

II. Romanze: Larghetto

The second movement is a breathtakingly beautiful, reverie-like recollection of fond memories, despite the transient turbulence in the middle. In Chopin’s letter to Woyciechowski, he wrote “The Adagio of the new concerto is in E major. It is not meant to create a powerful effect; it is rather a Romance, calm and melancholy; giving the impression of someone looking gently toward a spot which calls to mind a thousand happy memories. It is a kind of reverie in the moonlight on a beautiful spring evening.” There’s probably no better description than this.

III. Rondo: Vivace

While the first two movements were swiftly written, the third movement was completed with some difficulty in August 1830. Full of zeal, vigour and youthful energy, the final movement is based on Krakowiak, a syncopated folk dance from Kraków in 2/4 time. The styl brillant lives up to its full potential with the dazzling passagework, demanding much virtuosity from the soloist. Aside from the technical bravura, the underlying dancing pulse adds even more vivacity to the music. Eventually, the music is brought to a truly triumphant conclusion.

Below are some recommended recordings from me, which are by no means exhaustive!

Krystian Zimerman, Polish Festival Orchestra

© Deutsche Grammophon

Zimerman’s unremitting pursuit of perfection is astonishing – hand-picking each of the musicians of the orchestra, meticulously (or obsessively) planning the travel route, accommodation and meals for musicians during the concert tour, rehearsing for painstakingly long hours, etc. The outcome is equally remarkable, to say the least.

Right from the opening of Allergo maestoso, there was immaculate attention to orchestral parts, revealing many nuances that haven’t been heard of previously. Every sound was tastefully sculpted, each phrase scrupulously shaped, with rubato plentiful. Zimerman’s pianism was exceptional as usual – from the luscious tone colours in Romanze to the technical brilliance in Rondo. This is not only a legendary recording of this masterpiece but also of Chopin’s music as a whole.

Bella Davidovich, Sir Neville Marriner, London Symphony Orchestra

Having studied at the Moscow Conservatory under Konstantin Igumnov and Yakov Flier, Bella Davidovich shared the first prize with Halina Czerny-Stefańska in Chopin Competition in 1949. When I encountered this recording, I was immediately struck by the simplicity, naturalness and poetry in her Romanze. Long singing lines were maintained with bel canto by Davidovich, who was known for her singing tone and sensitive touch. It was completely devoid of sentimentality, coupled with a fine balance between classicism and romanticism, which many pianists overlook today. On the other hand, her reading of Rondo, albeit not the most extroverted, had such poise with a natural emphasis on the underlying pulse.

Kyohei Sorita, Andrzej Boreyko, Warsaw National Philharmonic Orchestra

In my humble opinion, this is the most outstanding rendition in Chopin Competition in 2021. Combining respect for tradition and creativity, Sorita unearthed so many details throughout (especially inner voices from the left hand), which asked for a deep understanding of the score. For instance, listen to his left hand from 9:20 to 9:28, from 14:18 to 14:22, and the inner line from 12:47 to 12:52. Meanwhile, the emotional aspect was never ignored – żal, poignancy, tranquillity and bliss were all distilled into the first movement, while the final movement was filled with ebullience and verve. What a delight!

Manchester Camerata to Host the UK’s First Centre of Excellence for Music and Dementia

by Frances Wilson, Interlude

According to the UK’s National Health Service, there are over 940,000 people in the UK with dementia, with 1 in 11 people over the age of 65 being most affected. The care of people living with dementia in the UK costs more than £34bn each year, with the Alzheimer’s Society saying that by 2040, 1.6 million people in the UK will have dementia.

Manchester Camerata’s Music Cafe at the Monastery in Gorton © Duncan Elliott

The Centre of Excellence for Music and Dementia is a new collaboration between the Manchester Camerata, a British chamber orchestra renowned for its innovative programming and pioneering outreach work, Alzheimer’s Society, and the University of Manchester. This will continue Manchester Camerata’s existing Music In Mind, a research-based music therapy programme, training a workforce of over 300 volunteer ‘Music Champions’, as well as developing Alzheimer’s Society’s ‘Singing for the Brain’, with the aim to offer musical support to people living with dementia across Greater Manchester. The long-term goal of the Centre of Excellence for Music and Dementia is to analyse how incorporating music into dementia care can reduce the need for intervention from healthcare services, reducing pressure on those services and care staff, as well as improving quality of life for patients, their carers, and families.

© Duncan Elliott

The Camerata’s Music Cafes, which have been running for more than a decade now, will provide support to over 1000 people currently living with dementia in the Manchester area. Created in partnership with the University of Manchester, these music champions use the fundamental principles of music therapy, bringing people living with dementia together to sing songs and perform vocal exercises that help improve brain activity and general wellbeing.

Bob Riley (CEO of Manchester Camerata) and Andy Burnham (Mayor of Greater Manchester) © Jay Cipriani

Speaking at the launch, Mayor of Manchester, Andy Burnham, said that Manchester is “a place that has always understood the power of music” and that the project will “unlock that power more fully and ensure that people everywhere, and in all settings, can benefit. For people living with dementia, who love music, the best thing you can do for them…is to reconnect them with that passion, because in that moment when they recognise that music, they are themselves again.” He highlighted the power of music to create connections: for families where a relative has dementia music can “give them glimpses of the person, and that’s why it’s so precious.” (interview with BBC Radio 3).

© Duncan Elliott

The project’s vital funding, totalling over £1million, will support three years of direct musical support activities across all of Greater Manchester’s 10 boroughs, starting in October 2024.

The project will have major significance in terms of ground-breaking research opportunities, and the intention is that the programme will grow into other areas of the National Health Service and areas of the country, with the hope that other musicians and other orchestras/ensembles may get involved.

“It’s one of the most joyous things any of us have ever experienced. It’s really changed how we view music and what it can do for people.” – Amina Hussain, flautist

Thursday, May 30, 2024

Alicia Keys - If I Ain't Got You (Orchestral) (Official Video - Netflix’...

LeAnn Rimes - You Light Up My Life - Official Music Video

/ leannrimes

Facebook:

/ leannrimes

Facebook:  / leannrimesmu. .

Twitter:

/ leannrimesmu. .

Twitter:  / leannrimes

/ leannrimes

.jpg)