by Hermione Lai

Alessandro Scarlatti became known as the “father of the Neapolitan school of Opera,” and his melodies feature fluid phrasing and innovative orchestration. It’s like a mixture of Baroque ornamentation with a proto-Classical clarity.

Alessandro Scarlatti

To commemorate his passing on 22 October 1725, let’s highlight the 10 most frequently performed and recorded arias, pieces that evoke deep emotions ranging from tender longing to stormy passion.

Radiant Dawn of Love

Alessandro Scarlatti crafted “Già il sole dal Gange” (Already the Sun from the Ganges) at the remarkably young age of 19 for his second opera, L’honestà negli amori (Honesty in Love Affairs).

It premiered on 3 February 1680 at the Teatro di Palazzo Bernini in Rome under the patronage of Queen Christina of Sweden. The work explores themes of romantic intrigue in an Algerian setting, and the aria is sung by the character “Saldino,” a pageboy.

The music pulses with a buoyant optimism, with the first rays of sunlight dancing across a serene river. This radiant dawn aria, with its soaring, sunlit phrases and graceful melismas, captures youthful love’s awakening. It is still a staple in vocal pedagogy today for its pure and flowing melodic line.

Love’s Anguish

Alessandro Scarlatti

Scarlatti’s opera Il Pompeo premiered in Rome in 1683, and it draws on the historical figure of Pompey the Great. Weaving a tale of political intrigue and personal betrayal, the aria “O cessate di piagarmi” (Oh, Cease to Torment Me) expresses the anguish of love’s torment, a recurring theme in Scarlatti’s operas.

Even at this early stage in his career, Scarlatti had already mastered the art of the da capo aria, using its ABA structure to deepen emotional contrast. It is a beautiful aria that pulses with raw, aching emotion.

The music unfolds like a quiet cry of the heart, its languid melody weaving a tapestry of longing and despair. Scarlatti distilled complex human suffering into a concise and expressive form.

Sighs of Solitude

Let’s stay with Il Pompeo for our next selection. “Toglietemi la vita ancor” (Take Away My Life Again) is a piercingly intense aria that lays bare the depths of despair and resignation.

The music moves at a very deliberate, almost funereal pace, its melody a fragile thread of anguish woven through a delicate web of sighs. The vocal line, with its aching leaps and lingering phrases, feels like a whispered plea for release from unbearable suffering.

Each note is heavy with the weight of betrayal and lost love, and the sparse continuo accompaniment underscores the solitude. The aria’s stark beauty and raw emotion have made it a lasting gem, and it is frequently performed independently.

Floral Fantasy

Alessandro Scarlatti

Alessandro Scarlatti composed “Le violette” (The Violets) for his opera Pirro e Demetrio, a work that premiered in Naples in 1694. It tells a tale of love and rivalry set against the backdrop of ancient kingdoms, focusing on the characters Pyrrhus and Demetrius.

The aria uses the metaphor of violets to express delicate, amorous sentiments, a common Baroque device. Scarlatti’s setting showcases his skill in crafting lyrical, expressive arias within the da capo form, balancing emotional depth with virtuosic elegance.

This aria blooms with delicate charm and youthful longing as the music dances with a gentle, almost pastoral grace. This delicate pastoral gem with lilting rhythms and floral imagery in the vocal line blends sweetness and melancholy in a da capo form that unfolds like a blooming flower.

Hypnotic Embrace

Alessandro Scarlatti composed “Dormi o fulmine di Guerra” (Sleep, O Thunderbolt of War) for his oratorio Giuditta. Unlike his operas, this sacred oratorio is based on the biblical story of Judith and Holofernes and focuses on dramatic storytelling through music without staging.

The aria, sung by Judith to the sleeping Holofernes, is a moment of tender irony, as she lulls the Assyrian general to sleep before killing him. It is essentially a lullaby that unfolds with a tender and almost hypnotic rhythm.

The vocal line, with its soft and undulating phrases, conveys a sense of calm and compassion, urging rest and peace upon a figure of strength and turmoil. The aria evokes a poignant blend of tranquillity and reverence, and it is often extracted for a standalone performance.

Moonlit Shadows

The cantata Correa nel seno amato (As the sun hastened toward its beloved) premiered in Naples in 1699. A semi-dramatic work, it was performed for courtly celebrations, and likely commissioned for a private aristocratic event.

The aria “Ombre opache” (Opaque Shadows) reflects a moment of emotional and dramatic intensity, and cast in da capo form, it uses subtle ornamentation and harmonic shading to evoke a vivid emotional landscape.

Undulating phrases over a continuo bass evoke a moonlit reverie with subtle harmonic shifts allowing the music to drift like a shadow over a misty landscape. The sinuous melody weaves a sense of quiet dread and longing.

The delicate vocal line feels like a whispered confession, heavy with the weight of hidden sorrow and forbidden desire. The sparse and mournful continuo accompaniment enhances the atmosphere of solitude and evokes a profound sense of introspection and unease.

Tomb-Side Whisper

Alessandro Scarlatti

The opera Mitridate Eupatore premiered in Vence in 1707. This operatic masterpiece centres on the historical figure Mithridates VI of Pontus, and weaves a tale of betrayal, power, and personal tragedy.

This tomb-side lament features profound and arching lines spiced up with chromatic descents. Blending sorrow with sublime tenderness, this heart-wrenching aria pulses with raw grief and tender devotion.

Unfolding at a funereal pace, this delicate lament seems to cradle the weight of loss. Drawn-out phrases and subtle ornaments convey a sense of intimate sorrow, as the character is whispering to a departed loved one. Here, Scarlatti captures human vulnerability, making it a standout piece often performed independently in recitals.

Tragedy in the Minor Key

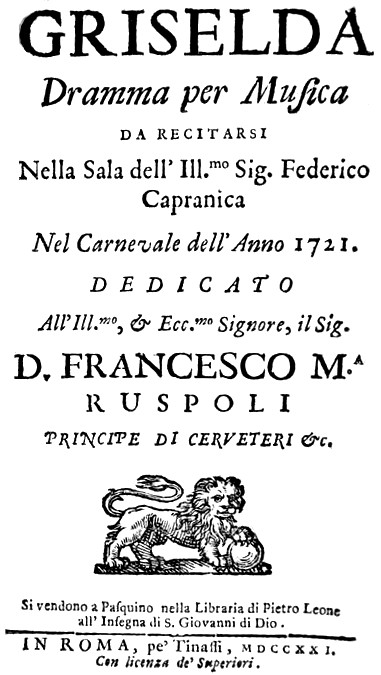

Alessandro Scarlatti’s Griselda – title page of the libretto

Premiered in January 1721 in Rome, Griselda is based on Boccaccio’s tale of a woman tested by the cruel trials of loyalty and love. Composed late in Scarlatti’s career, this opera reflects the composer’s refined mastery of the da capo aria, lending dramatic expressiveness with intricate vocal writing.

The aria “Figlio! Tiranno! O Dio!” (Son! Tyrant! O God!) is a visceral outpouring of anguish and conflict, charged with dramatic intensity. Set in a turbulent minor key, the aria surges with a restless, almost frantic energy.

Its jagged melodic lines and abrupt rhythmic shifts mirror a heart torn between love, betrayal, and despair. Marked by impassioned leaps and anguished phrasing, this aria feels like a cry wrenched from the depths of a tormented soul. Here, raw emotion meets melodic elegance.

Fleeting Beauty—Eternal Music

The serenata Ferma omai, fugace e bella (Stay Now, Fleeting and Beautiful), was probably written for a private occasion, and it celebrates mythological and pastoral themes common to the genre.

The aria, “Va, va che I lamenti miei” (Go, Go, for My Laments), brims with yearning and resignation. The music flows with a graceful yet sorrowful lilt, its melody weaving a delicate tapestry of heartbreak and quiet defiance.

Alessandro Scarlatti, a cornerstone of the Neapolitan Baroque, masterfully blended lyrical expressiveness with dramatic intensity, crafting arias that capture the depths of human emotion with vivid melodic lines and refined da capo structures.

As we commemorate his 300th anniversary, we celebrate his artistry of infusing both sacred and secular works with profound emotional resonance. Just listen to the aria “While I Rejoice in Sweet Oblivion” for the seamless balance between virtuosic flair and evocative storytelling. His innovative use of melody, harmony, and orchestration ensures his works remain timeless.

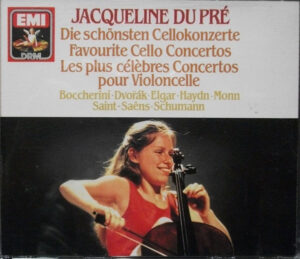

Jacqueline Mary du Pré (1945-1987) is arguably one of the most gifted cellists of our time. She is particularly remembered for her legendary debut performance of Elgar’s Cello Concerto in E minor (one of the favourite cello concertos of all time), which she performed with the BBC Symphony Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall in 1962 under Rudolf Schwarz.

Jacqueline Mary du Pré (1945-1987) is arguably one of the most gifted cellists of our time. She is particularly remembered for her legendary debut performance of Elgar’s Cello Concerto in E minor (one of the favourite cello concertos of all time), which she performed with the BBC Symphony Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall in 1962 under Rudolf Schwarz.

In 1966, Du Pré was invited to perform the Brahms F major Sonata with Israeli conductor and pianist Daniel Barenboim. The two quickly fell in love and married in May the next year. TIME magazine wrote, “Thus began one of the most remarkable relationships, personal as well as professional, that music has known since the days of

In 1966, Du Pré was invited to perform the Brahms F major Sonata with Israeli conductor and pianist Daniel Barenboim. The two quickly fell in love and married in May the next year. TIME magazine wrote, “Thus began one of the most remarkable relationships, personal as well as professional, that music has known since the days of