by

Maria Curcio could easily have been one of the most famous pianists of the twentieth century.

So why do only a handful of classical music lovers know her name today? What kept her from the solo career she seems to have been born for?

Today, we’re looking at the remarkable story of Maria Curcio: her astonishing precocity, the story of how she escaped the Nazis, and how she came back from wartime health issues to become one of the most influential piano teachers of all time.

Maria Curcio’s Childhood

Maria Curcio

Maria Curcio was born in August 1918 near Naples, Italy.

Her father was a wealthy Italian businessman, and her mother was a Jewish Brazilian pianist who studied under a pupil of composer/pianist Ferruccio Busoni.

Maria began taking piano lessons from her mother when she was three years old.

She started giving public performances that same year, expressing delight at the toys that the appreciative audience handed her.

Curcio’s Unhappy Childhood

Curcio’s parents chose to homeschool her, so she’d have as much time as possible to pursue her musical studies and tour.

She didn’t go to school and didn’t play with other children. As an elderly woman, she described her childhood as “not a happy one.”

When she was seven, she was invited to perform for Mussolini. However, on the day of the performance, she threw a tantrum and hid underneath a tablecloth, refusing to come out. According to legend she claimed he was “ruining our country.”

Studying With Legendary Teachers

Maria Curcio

Despite that scandalous no-show, Italian artists took note of the prodigy.

Composer Ottorino Respighi invited her to perform at his home in Rome, and she studied for a time with composer and pianist Alfredo Casella.

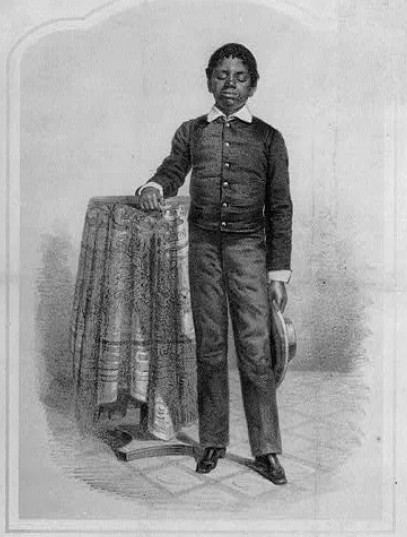

Artur Schnabel

She also worked with pianist and conductor Carlo Zecchi, a student of legendary pianist and pedagogue Artur Schnabel.

Later, after her graduation from the Naples Conservatory at the age of fourteen, she spent a year in Paris studying with Nadia Boulanger, the most influential music teacher of the twentieth century.

Meeting Schnabel

Karl Ulrich Schnabel, 1940’s © schnabelmusicfoundation.org

When she returned to Italy, she played for pianist Karl Ulrich Schnabel, Artur’s son.

Karl knew his father didn’t like working with children, but Curcio was simply so dazzling that he urged his father to hear her play.

So Zecchi took Curcio to Lake Como, where the elder Schnabel was ensconced, teaching a series of masterclasses.

Schnabel was blown away by her, declaring her “one of the greatest talents I have ever met.” He quickly asked her to be his pupil.

Curcio would also work intensively with Schnabel’s wife, singer Therese Behr, providing accompaniments to her students. This training gave her important insights into vocalists’ approaches to music. She later said that she learned just as much from Behr as she did Schnabel.

Through Schnabel, she met conductor Fritz Busch, who offered to work with her while Schnabel was touring. This invaluable connection enabled her to hear legendary opera and orchestral performances.

“You can’t play Mozart if you don’t know the operas,” she later said in an interview. “Because Mozart was vocal.”

A Promising Career Interrupted by War

In 1939, when Curcio was nineteen, she made her London debut.

Unfortunately for Curcio, 1939 was one of the worst years of the century to launch a European career.

That September, Hitler invaded Poland, sparking World War II. Months later, in the spring of 1940, the Nazis made another push and invaded multiple other European countries, including Holland.

Staying in Amsterdam During the Occupation

Upon the outbreak of war, Schnabel’s Jewish secretary, Peter Diamand, moved back to his home in Amsterdam. Curcio joined him and continued her concert career there.

After the Nazis forbade Jews from playing music in public, she protested by refusing to concertize. “I wouldn’t accept to play in a country where not everybody had equal rights.”

Her parents begged her to return to Italy, even involving the Italian ambassador and consul to convince her. But she was deeply loyal to her colleague, and she wasn’t about to abandon him.

Saving Peter Diamand

Diamand ended up being arrested by the Nazis and interned in a Dutch concentration camp. It was only through Curcio’s intervention and string-pulling that he and his mother were kept from being sent to an extermination camp deeper in Nazi territory.

The Diamands were freed, but were told that they would be prime candidates for re-arrest in the near future. It became clear they had no other option but to go into hiding.

Curcio coordinated the dangerous work of securing food and forged identity papers for them. The trio hid in cramped conditions, suffering extensive physical and mental traumas from their ordeal.

During their time underground, Curcio developed tuberculosis and malnutrition. It would take years of work for her to regain use of her limbs and enough physical strength to play piano at a high level again.

While filming a 1980s documentary, Diamand remarked, “It was typical for Maria. I mean, as I said, there are no compromises, and when it means risking one’s life, she risked her life.”

“Would you say that part of the price she paid was her concert career?” the interviewer asked him.

“Indeed,” Diamand replied. “Indeed. She ruined her health.”

Despite the intensity and desperation of their circumstances, or maybe because of them, Curcio and Diamand fell in love. They married in 1947.

Recovering from the War

After the war, she entered a sanitarium to recover from her tuberculosis infection.

She later told a student that while she was bedbound, she spent a huge amount of time thinking about how to play the piano, working out technical and musical problems in her head.

(During this time, fellow patient, conductor Otto Klemperer, tried flirting with her, but only succeeded in spilling orange juice on her.)

She slowly returned to playing during the 1950s.

Although she had lost a huge amount of strength and time, she had also built up a reserve of inner strength and internal conviction that would serve her well as a teacher.

Making Musical Friends

She also had the benefit of being married to Diamand, who, in 1948, became director of the Holland Festival.

As she recovered, through her husband’s work, she was able to remain connected with the greatest musicians of the era.

During this second phase of her performing career, she worked with stars like Benjamin Britten and his partner Peter Pears, Otto Klemperer, Pierre Monteux, and Elisabeth Schwarzkopf.

Conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler also wanted to work with her, but, interestingly, she declined. Although she admired his music-making, she couldn’t justify working with someone whom she felt had legitimised the Nazis.

He sent her a bouquet of roses as a token of his admiration, and she returned the generous gesture by sending him a gift of oranges (a rare treat in late 1940s Europe), but she still refused to make music with him.

In 1963, the year she turned forty-five, she retired from public performance, choosing to focus on teaching instead.

Moving to Britain

In 1965, Peter Diamand was named the director of the Edinburgh International Festival, a position he would hold for thirteen years. The couple moved from Amsterdam to the United Kingdom.

This appointment helped to solidify the family’s connection with Benjamin Britten, who had several of his most important works premiered at the Edinburgh Festival in the 1950s and 1960s.

Curcio often played four-hand piano with him, and the two artists exchanged ideas and inspiration.

Britten helped her get a position teaching at the Royal Academy of Music in London. She also joined the jury of the prestigious Leeds International Piano Competition.

Her Teaching Career

Maria Curcio and Simone Dinnerstein

After she settled in Britain, her reputation as a teacher began to grow exponentially.

Many of the most beloved pianists of the last and current centuries visited her studio seeking advice, including:

- Martha Argerich

- Simone Dinnerstein

- Leon Fleisher

- Radu Lupu

- Yevgeny Sudbin

- Inon Barnatan

- Mitsuko Uchida

And those are only a few of many.

Later Life and Death

In 1971, when she was fifty-three, it came out that Diamand had an affair with actress Marlene Dietrich. He and Curcio divorced that year. However, he continued to speak positively of her and agreed to be interviewed for a documentary in the 1980s.

Through the personal turmoil, she continued teaching and redoubling her devotion to her career and her students.

In her eighties, she moved to the coastal city of Porto, Portugal, where she died in 2009. She was ninety years old.

The Legacy of Maria Curcio

Thankfully, before her death, a couple of priceless documentaries were made about her, featuring interviews with her, Diamand, and some of her students.

One BBC Scotland documentary from the 1980s begins with her telling a pupil who is playing the Chopin G-minor Ballade:

The sound that we need on the piano must always not express just notes; it must express feelings.

It must be immediately the transmission between your soul and the soul of the composer, which goes through your ear and your hands, must go immediately to us.

It’s the soul of Chopin which is crying, which is loving.

It’s not the notes.