by

Throughout music history, there have been many incredible children who have demonstrated an astonishing, unnervingly early mastery of their art.

Some went on to become the greatest musicians of their age. Others have vanished from our collective memories.

One thing they all have in common is that the stories of their childhoods are all fascinating.

Today, we’re looking at the backgrounds, education, and jaw-dropping accomplishments of some of the greatest child prodigies of all time.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart is likely the most famous musical prodigy of all time. He was born in 1756, the second surviving child of court musician Leopold Mozart and his wife.

His older sister Maria Anna, nicknamed Nannerl, began taking keyboard lessons when she was seven and Wolfgang was three.

Nannerl later wrote:

He often spent much time at the clavier, picking out thirds, which he was ever striking, and his pleasure showed that it sounded good…

In the fourth year of his age, his father, for a game as it were, began to teach him a few minuets and pieces at the clavier… He could play it faultlessly and with the greatest delicacy, and keeping exactly in time…

At the age of five, he was already composing little pieces, which he played to his father, who wrote them down.

Despite Leopold’s reputation as a pushy stage father, when it came to his early attempts at composition, Wolfgang was clearly the instigator. His early manuscripts are stained with ink and bear evidence of his enthusiasm for composing.

After both Nannerl and Wolfgang became prodigies, Leopold decided to take leave from his job and accompany them on a tour of Europe. Over a period of years, the Mozart family traveled across Austria, Germany, France, and Britain, showcasing the talents of both children.

Wolfgang composed on the road and wrote his first symphony when he was eight (possibly with the assistance of Nannerl).

Thomas Linley the Younger

Thomas Linley the Younger

Thomas Linley the younger was born the same year as Mozart, in 1756, in Bath, England. His father shared his name, so the son often went by the nickname Tom.

Thomas Linley the Elder made his living as a music teacher and local impresario, and eventually became the most famous musical patriarch in Bath.

Presenting concerts became a family affair. His children, including Tom, started out by collecting tickets, but once they began showing musical talent, Thomas the Elder had them appear onstage. The musical performances of the Linley children helped secure the family’s social and economic fortunes.

Tom gave his concerto debut on violin in the summer of 1763, just after his seventh birthday. That year, he began studying composition with William Boyce, Master of the King’s Musick.

In between lessons, the Linleys began touring Britain. In 1767, two of the Linley siblings performed at a Covent Garden performance of The Fairy Favour by Thomas Hull. Tom played the violin, sang, and danced, receiving rapturous reviews.

In 1768, the year he turned twelve, Tom went to Italy to study violin playing and composition with Florentine master Pietro Nardini. Tom became Nardini’s favourite pupil.

In April 1770, the month he turned fourteen, he met Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who was traveling through Italy with his father to concertize and study. The two boys became fast friends. English writer Charles Burney wrote of their meeting:

The Tommasino, as he is called, and the little Mozart, are talked of all over Italy as the most promising geniuses of this age.

When Wolfgang had to leave for the next stop on his tour, both boys were upset at having to separate. Leopold Mozart wrote to his wife, who remained in Salzburg during the Italian tour:

These two boys performed in alternation during the whole evening, constantly embracing each other.

The next day, the little Englishman, a very dear boy, had his violin brought to us and played the whole afternoon; Wolfgang accompanied him on the violin.

The day after, we dined with Msr. Gavard, the Grand Duke’s financial administrator, and these two boys played in alternation the whole afternoon, not as boys, but as men!

Little Thomas accompanied us home and cried the most bitter tears because we were leaving the next day.

Tragically, Tom would never get to develop into a fully fledged performing artist or composer. He died in August 1778 at the age of twenty-two in a boating accident.

Mozart would never forget his friend, telling tenor Michael Kelly years later that Tom was “a true genius” and, had he lived, would have become one of the great musicians of the age.

William Crotch

William Crotch

William Crotch was born in Norfolk, Britain, in the summer of 1775. His father was a carpenter and instrument builder.

When William was two years old, he began performing on an organ that his father had built. He made fast progress. The following year, his mother brought him to London, where he performed for King George III, playing on an organ at St. James’s Palace.

One magazine reported:

As soon as he has finished a regular tune, or part of a tune, or played some little fancy notes of his own, he stops, and has some of the pranks of a wanton boy; some of the company then generally give him a cake, an apple, or an orange, to induce him to play again…

Later in life, Crotch admitted that this strategy to get him to play had spoiled him.

His first oratorio was performed when he was just fourteen.

He attended Oxford University and became a professor there in 1797, when he was twenty-two. Over the course of his career, he taught a number of important British musicians.

Felix Mendelssohn

Felix Mendelssohn

Felix Mendelssohn was born in early 1809 to a wealthy and musical banking family. He grew up to become one of the most impressive musical prodigies in classical music history.

A variety of influences played into Felix’s early development.

His older sister Fanny Mendelssohn was a child prodigy herself, and the two siblings bonded over their musical studies.

The wider family also valued the arts and education, and their wealth enabled both Fanny and Felix to explore their musical interests in a supportive environment.

In addition, the Mendelssohns’ social cachet meant that all manner of artistic and intellectual leaders of the nineteenth century flocked to the family home.

In short, it was the perfect environment for a prodigy to develop.

Felix began studying the piano with his mother when he was six. Throughout his childhood, he had a number of first-rate teachers, including Marie Bigot (who had worked with Beethoven) and Ludwig Berger (who had studied with Clementi). He also began studying composition.

His parents paid for a private orchestra to perform at house concerts, and Felix began writing music for the ensemble. As a child, he wrote thirteen string symphonies for them.

His first published work, a piano quartet, appeared when he was just thirteen. (It is believed that his father helped to ensure the publication of the work.)

But Felix’s father wasn’t encouraging his son out of pity: the works were of genuine, astonishing quality. In fact, Mendelssohn’s string octet, written for four violins, two violas, and two cellos, is widely considered to be one of the finest works of chamber music ever written…and he was only sixteen when he composed it!

The following year, he followed the Octet up with his Overture to a Midsummer Night’s Dream, which still appears on concert programs today.

In 1821, when Felix was twelve, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe compared Felix to Mozart, suggesting that between the two, Felix might be even more talented. It was a shocking comparison, especially because Goethe had met Mozart when he was a touring seven-year-old prodigy.

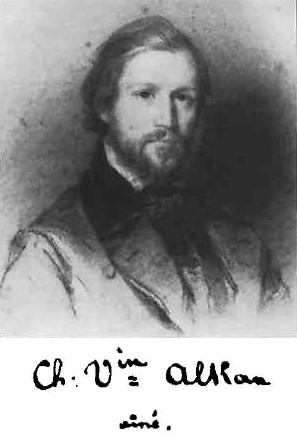

Charles-Valentin Alkan

Charles-Valentin Alkan

Charles-Valentin Alkan was born in Paris in 1813 to a musical family. His father was a musician and head of a private music school, and all five of his siblings went into music professionally in some capacity.

His musical talent was obvious from an early age. Astonishingly, he took his first audition for the Paris Conservatoire solfège class when he was just five years old. One of his examiners wrote that he had “a pretty little voice.”

A year later, he auditioned for the piano class, too. That time the examiners wrote, “This child has amazing abilities.”

In 1821, when he was seven, he won a first prize in solfège. That same year, he gave his first public performance on violin.

He also began studying piano, and at the age of ten, he won a piano prize to add to his collection.

His opus 1 for solo piano was written in 1828, when he was just fourteen. As the work makes clear, he was already a master musician.

Camille Saint-Saëns

Camille Saint-Saëns

Camille Saint-Saëns was born to a Parisian family in 1835. Tragically, just a few months after Camille’s birth, his father died of tuberculosis.

He spent the first two years of his life in the countryside with a nurse, and was only reunited with his widowed mother in Paris in 1837.

Before his third birthday, he began picking out melodies on the family piano. His great-aunt was his first piano teacher, but he quickly learned all that she had to teach. When he was seven, he began studying with Camille-Marie Stamaty.

He began playing for small groups when he was five years old, but his mother made sure that he didn’t concertize too widely as a very young boy.

He gave his public debut when he was ten in a remarkable double-header, playing Mozart’s fifteenth piano concerto and Beethoven’s third concerto.

In 1848, when he was thirteen, he enrolled at the Paris Conservatoire. Over the course of his studies there, he became an organ virtuoso as well as a piano virtuoso.

He began his formal composition studies when he was fifteen. That same year, he wrote a symphony in A-major, although he never published it.

He capped off his student career by writing his Op. 1 for harmonium in 1852, the year he turned seventeen.

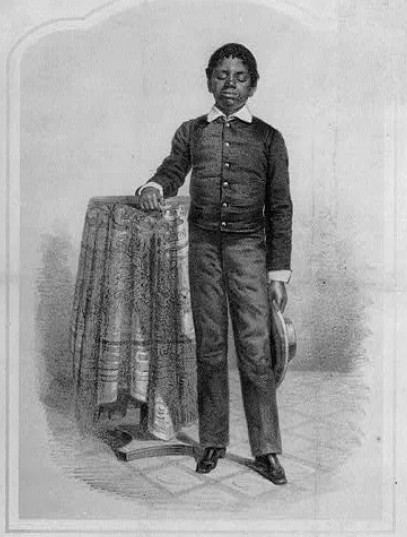

Blind Tom Wiggins

Blind Tom Wiggins

Thomas Wiggins was born on a Georgia plantation in the spring of 1849. His lot was unimaginably difficult: both of his parents were enslaved, and he was born blind.

Because his blindness kept him from doing work that an enslaved person would generally do, he was permitted to wander the grounds as a child.

One day, he heard one of the plantation owner’s daughters play piano, and he was immediately intrigued. He was allowed access to the piano and was composing by the time he was five.

The master of the plantation, a man named General Bethune, saw a money-making opportunity. He moved Tom into his own room and made a piano available to him. He began playing twelve hours a day.

Because of his lack of traditional formal training, he focused on reproducing the sounds he heard around him, like rainstorms and birdsong.

When he was eight years old, General Bethune hired a promoter to oversee Tom’s career. Tom began a grueling touring schedule, being marketed as a freak of nature and compared to an animal. He began earning the family the modern equivalent of millions of dollars a year. Of course, Tom and his family saw none of that money.

To publicise Tom, Bethune would hire musicians to play for Tom, then challenge him to reproduce what he’d just heard, which he could always do. That extraordinary memory resulted in his learning thousands of pieces of music by ear.

In 1860, when he was eleven, he appeared at the White House for James Buchanan, becoming the first Black artist to give a command performance there.

After the Confederacy lost the American Civil War, Bethune sent a teenage Tom to Europe. While there, he received testimonials from pianist Ignaz Moscheles and conductor Charles Hallé, attesting to his genius.