By Francis Wilson, Interlude

Credit: https://static1.squarespace.com/

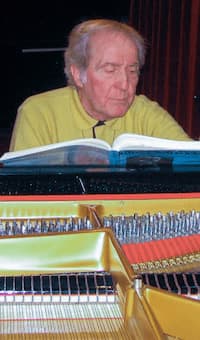

British pianist Stephen Hough, speaking on BBC Radio 4’s Desert Island Discs programme

The pianist’s life is, by necessity, lonely. One of the main reasons pianists spend so much time alone is that we must practise more than other musicians because we have many more notes and symbols to decode, learn and upkeep. This prolonged solitary process may eventually result in a public performance, at which we exchange the loneliness of the practise room for the solitude of the concert platform.

Most of us do not choose the piano because we are loners – such decisions are usually based on our emotions, motor skills or the aural appeal of the instrument. For me, as a child – and an only child – the piano was a companion and a portal to a world of exploration, fantasy and storytelling. It remains a place to retreat to and time spent with the instrument and its literature can be therapeutic, rebalancing and uplifting. For many of us, being alone is the time when the sense of being at one with the instrument is strongest.

In addition, there is time alone spent listening to recordings – one’s own (for self-evaluation) and by others (for inspiration and ideas on interpretative possibilities, or purely for relaxation) – and time simply recovering from practising and refocusing in readiness for the next session. Many pianists tend to be loners – the career almost demands it and self-reliance is something one learns early on, as a musician – but that does not necessarily make pianists lonely or unsociable.

To me it’s always about connection – connecting with parts of myself, with the thoughts and feelings of the composer, and ultimately sharing with an audience. It’s travelling through time and space to experience other eras and cultures…..I can’t think of anything that makes me feel less lonely!

Stephen Marquiss, pianist & composer

The life of the concert soloist is a strange calling, yet many concert pianists accept the loneliness as part of the package, together with the other accessories of the trade. The concert pianist experiences a particular kind of solitude (as noted by Stephen Hough in the quote at the beginning of this article). The solitude of travelling alone – the monotony of airport lounges, the Sisyphean accumulation of air miles, nights spent alone in faceless hotels. Dining alone, sleeping alone, breakfast alone, rising early to practise alone. And there is the concert itself: waiting backstage, alone, in the green room, and then the moment when you cross the stage, entirely alone….. The pianist Martha Argerich has described the “immense” space around the piano that has always made her feel alone on stage. But it is this aloneness, this separation, which the solo pianist exploits for the purpose of captivating and seducing the audience, drawing them into his or her own private world for the duration of the performance.

I suppose being an introvert in a ‘public performance’ profession has been my greatest challenge. It isn’t straightforward, of course – I seem to have a deep need to communicate music to an audience and get their reaction, and I love to be appreciated, but there are many other aspects of being ‘on show’ that don’t come naturally. I’m very interested in people, but I’m quite a private person and need lots of time to myself.

Susan Tomes, pianist and writer

The traditional positioning of the piano on stage, so that the pianist sits side on to the audience, heightens this sense of separation and aloneness. In a concert, the pianist must navigate a path between private, subjective feelings and public expression in a curious display of both isolation and exhibitionism. The power of performer, and performance, is this separateness from the mass of audience. Some performers may exploit this to create a sense of “us and them”, while others are adept at creating an intensity or intimacy of sound and gesture during which the audience may feel as if they have a private window onto the pianist’s unique world, in that moment.

Up there on the stage, one can feel more alone than anyone would ever care to be, yet it can make one better than one thinks possible because one’s ego is constantly being tested when one plays. To meet a Beethoven sonata head on, for example, it stops being about you – how fast you can play, how technically accomplished you are. Instead it is about getting beyond oneself, becoming ego-less, humble in the face of this great music, developing a sense of oneness with the composer…..

After the performance, when the greeting of the audience and CD signing is over, the pianist may happily retreat to his or her solitary practise room or studio. Many of us long for this special solitude and actively relish the time spent practising alone.

The internet and social media have, for many of us, been a huge support in relieving feelings of loneliness and separation. Facebook, Twitter and other social media platforms enable us to connect with pianists and other musicians around the world, allowing us to preserve our solitude, while also engaging meaningfully with others when required.

Khatia Buniatishvili is adamant about the freedom of her performances, and she defends her right to “re-appropriate each work and to perform them without necessarily respecting the tradition or model imposed by her predecessors.” The human being stands squarely in the center of her art, as “we can subtly reveal our emotions all the while staying perfectly intimate with our instrument.” Emotion is her guiding and motivating force, and she is in love with complexity and paradoxes, not complications and oppositions. Her music is fundamentally bound to political activism, as she is involved in numerous social rights project, including among others the DLDwomen13 Conference in Munich, or the United Nation’s 70th Anniversary Humanitarian Concert benefiting Syrian refuges. Khatia Buniatishvili refuses all invitations to perform in Russia as long as president Putin is in power. As to Khatia’s musical performances, they have either been called “hauntingly original” or “beyond the eccentricity of Planet Pogorelich.” This fundamental disagreement depends on how commentators interpret the communicative aspects of music, and that surely includes attire and all other performative aspects.

Khatia Buniatishvili is adamant about the freedom of her performances, and she defends her right to “re-appropriate each work and to perform them without necessarily respecting the tradition or model imposed by her predecessors.” The human being stands squarely in the center of her art, as “we can subtly reveal our emotions all the while staying perfectly intimate with our instrument.” Emotion is her guiding and motivating force, and she is in love with complexity and paradoxes, not complications and oppositions. Her music is fundamentally bound to political activism, as she is involved in numerous social rights project, including among others the DLDwomen13 Conference in Munich, or the United Nation’s 70th Anniversary Humanitarian Concert benefiting Syrian refuges. Khatia Buniatishvili refuses all invitations to perform in Russia as long as president Putin is in power. As to Khatia’s musical performances, they have either been called “hauntingly original” or “beyond the eccentricity of Planet Pogorelich.” This fundamental disagreement depends on how commentators interpret the communicative aspects of music, and that surely includes attire and all other performative aspects.