By Georg Predota, Interlude

Ignacy Jan Paderewski

Apparently, he was a skilled orator, and “every speech was a masterpiece of clear thinking and brilliant verbal form.” Musicianship and politics aside, Paderewski was a great humanitarian and philanthropist who established funds for various political and artistic organizations. After his 1895/96 American Tour, he established a fund “for the encouragement of American composers. He placed a sum of 2,000 dollars into the hands of three trustees, of which the interest was to be devoted to triennial prizes for composers of American birth irrespective of age or religion.” Only a couple of years later, Paderewski established a similar fund for Polish Composers in Leipzig in 1898. A panel of judges was quickly assembled, consisting of Arthur Nikisch, Carl Reinecke, Julius Klengel and the music critic Friedrich Pfau. Submissions were to be judged in the genres of chamber music, the symphony, and the concerto.

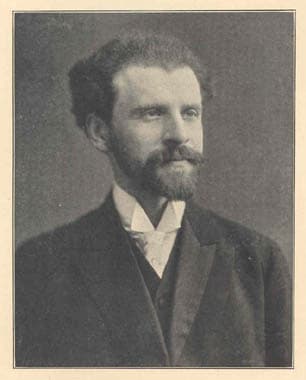

Sigismond Stojowski

While the chamber music prize was awarded to the “String Quartet” by Woitech Gavronski, the symphony prize went to Sigismond Stojowski (1870-1946). For a good many commentators, Stojowski is considered the missing link between Frédéric Chopin and Karol Szymanowski. Straddling Polish music between the second half of the 19th century and the dawn of modernism, his music somehow never managed to enter the repertoire. Stojowski had been a Paderewski student, and the Symphony in D minor, Op. 21 handily was awarded the first prize at the Leipzig 1898 competition. It was premiered as part of the competition festivities under the baton of Arthur Nikisch. Significantly, it was the first ever published symphony for orchestra by a Polish composer. Stojowski was urged to revise the final movement, and the premiere of the final version took place on 15 November 1900 with the Berlin Philharmonic.

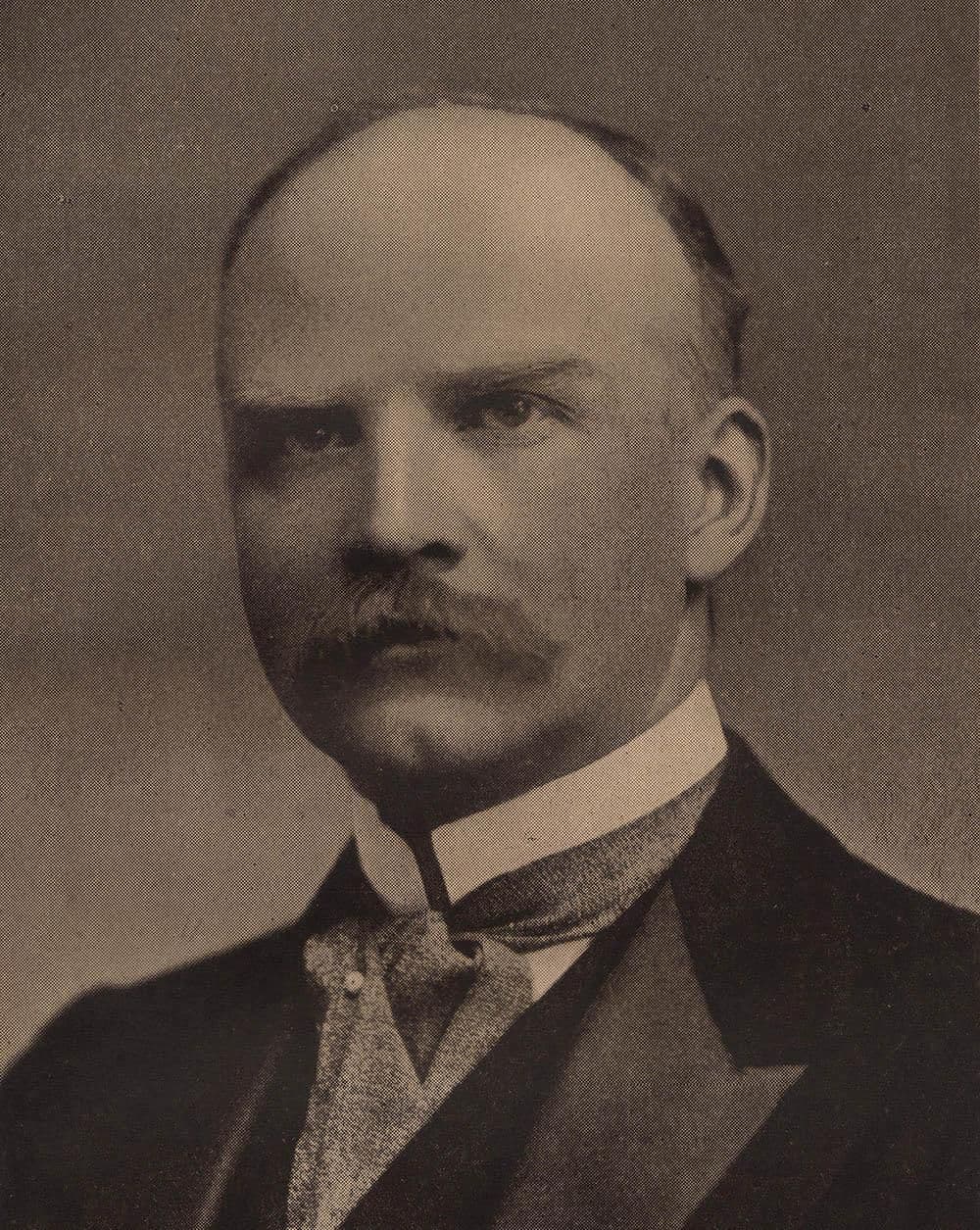

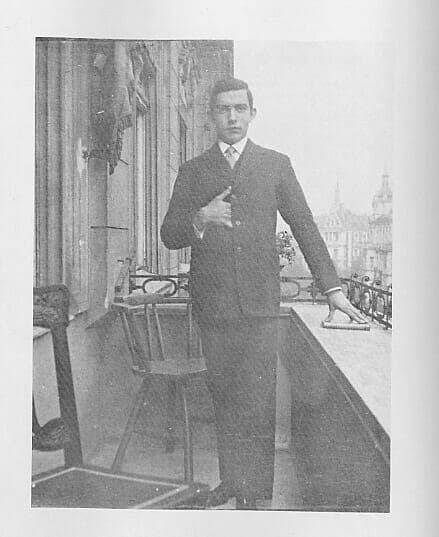

Emil Młynarski

The concerto prize went to Henryk Melcer-Szczawiński, who won with his Piano Concerto No 2. However, another first was awarded to the Violin Concerto Op. 11 by Emil Młynarski (1870-1935).

Born in Kibarty near Suwałki , Młynarski started his studies at the St Petersburg Conservatory at the age of nine and counted Leopold Auer, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, and Anatoly Lyadov among his teachers. He also took classes with Anton Rubinstein and Pyotr Tchaikovsky, and he began to focus on developing his instrumental career. He would feature as the soloist at the Imperial Music Society and became second violinist of the Leopold Auer Quartet. During a stay in Odessa, Młynarski composed his Op. 11 concerto, a work he submitted to the Paderewski Competition. Crafted in the Romantic tradition, the concerto features a number of surprising harmonic solutions, and the flowing melodies are sprinkled with a dash of originality.

Henry Kimball Hadley

Due to organizational difficulties and political infighting, the Leipzig Paderewski Prize Competition did not continue. As such, Paderewski took the concept and transferred it to the emerging fund already envisioned in the United States. On 15 May 1900, he formally founded the Ignacy Jan Paderewski Trust of 10,000 dollars and defined a series of prizes for the encouragement of American composers. Composers would submit works anonymously, under an assumed name or motto, accompanied by a sealed envelope containing the composer’s name. The initial categories, limited to American composers, were pieces for full orchestra, pieces for chorus with orchestra accompaniment with or without solo voice parts, and pieces for chamber music for any combination of instruments. The rules also stipulated that the works could not have been previously performed in public or offered at any previous competition. 68 compositions were submitted in 1901, and Henry Kimball Hadley, who had studied with Eusebius Mandyczewski in Vienna, won with his Symphony No. 2 in F minor. Subtitled “The Four Seasons,” the work begins with “Winter” before the composer musically encodes the remaining seasons.

The Paderewski Prize for American Composers was awarded every three years from 1901 to 1948. The first prize for a symphonic work carried a cash reward of $1,000, and chorus and chamber compositions received $500, respectively. “The prestige of the prize far outweighed the cash benefit, as in most cases, the publicity from the prizes led to assurances of international performances.” Horatio William Parker won in the chorus category with “A Star Song,” scored for solo voice, chorus, and orchestra, and the chamber music award in 1901 went to Arthur Bird’s “Serenade for Wind Instruments.” Born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Bird studied in Europe and spent a year with Franz Liszt at Weimar. His music was popular in Europe, and he was also active as a correspondent and music critic.

Every competition needs a scandal, and that’s exactly what happened at the Paderewski Prize for American Composers in 1905. Approximately 80 manuscripts were submitted, including a symphonic work titled “Palisades Overture” by John Rice, Jr., of Hudson Heights, New Jersey. In the event, the manuscript submitted was actually the “Le Corsaire Overture” by Hector Berlioz. One of the jurors, the conductor Walter Damrosch had recently presented the work, and the ruse was easily detected. The trustees angrily delivered a letter to Rice demanding an explanation, who denied any knowledge. As expected, there was plenty of media coverage, but the competition was unaffected. Judges made the announcement on 17 November 1905, and the sole winner that year was Arthur Shepherd’s (1880-1958) “Overture Joyeuse.”

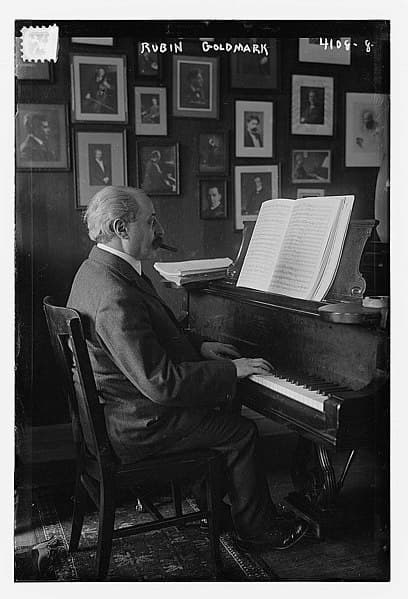

George Whitfield Chadwick, Horatio William Parker, and the founding conductor of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, Frank Van der Stucken, chaired the 1909 competition. Paul Hastings Allen won the symphonic category with his “Pilgrim Symphony” in D Major, and David Stanley Smith was awarded first prize for his cantata “The Fallen Star,” Op. 26. Rubin Goldmark (1872-1936) won the chamber music award with his Piano Quartet in A Major, Op. 12.

Rubin Goldmark

The nephew of composer Karl Goldmark, he studied at the Vienna Conservatory until 1891 and returned to the United States to take up appointments in piano and music theory at the National Conservatory in New York City. He took composition lessons from Antonín Dvořák, and became best known as the teacher of Aaron Copland and George Gershwin.

The Paderewski Prize for American Composers took a break between 1911 and 1919, but restarted after the end of World War I in 1921. It was then held at the New England Conservatory and henceforth offered prizes in only two categories: symphonic and chamber music. No award was given in the symphonic category “for a lack of submissions meeting contest criteria,” but the chamber music award went to Wallingford Constantine Riegger (1885-1961).

Wallingford Constantine Riegger

Born in the state of Georgia, the family eventually moved to New York City. He was a gifted cellist and a member of the first graduating class of the Institute of Musical Art, later known as the Juilliard School. Riegger spent three years in Berlin and studied with Max Reger, and after a couple of years back home, he returned to Europe to conduct opera in Germany. He later taught at Drake University in Iowa, and his earliest surviving works are scored in a lush Romantic idiom. Such is the case with the Piano Trio that won him the Paderewski Prize in 1921. It would also be his first published composition.

Charles Haubiel

The trustees Arthur Dehon Hill and Joseph Adamowski announced the winners of the 1928 competition from Boston. Hans Levy Heniot (1900–1960), brother-in-law of Alexander Kipnis took the prize in the symphony category while Homer Corless Humphrey (1880–1966) won the chamber music entry with his Introduction and Allegro: Risoluto for Violin, Violoncello, and Piano. The 1934 winners were announced from New York, and Allan Arthur Willman took the symphony award with his tone poem “Solitude.” Charles Trowbridge Haubiel (1892-1978) received an honorable mention for his piano work “Mars ascending.” He was born in Ohio but educated in Berlin and New York City. He studied piano under Josef and Rosina Lhévinne, and counterpoint with Rosario Scalero. Haubiel received an appointment to teach piano at the Institute Musical Art, and at New York University. He composed three operas and a good deal of orchestral and chamber music. Tellingly, his music “has been described as a combination of Johannes Brahms and Claude Debussy.

Composers of distinction for the 1938 competition included Walter Helfer, who received first prize for his “Prelude to a Midsummer Night’s Dream,” and Morris Mamorsky for his “Concerto for piano and orchestra.” Three years later the trustees announced the winners for the 1942 competition from Boston.

Gardner Read

Gardner Read (1913-2005) hailed from the state of Illinois, he initially studied piano and organ alongside counterpoint and composition at the School of Music at Northwestern University. A four-year scholarship saw him attend the Eastman School of Music, and he subsequently was active as a composer and administrator. He authored several textbooks on musical notation and technique and composed roughly 150 major works, “all of which demonstrate formidable technique and craftsmanship. His big orchestral canvases are especially notable for their exotic and often graphic colour.” These characteristics undoubtedly swayed the judges, and his foreboding second symphony won first prize in the 1942 Paderewski Fund Competition. The work premiered on 26 November 1943 with the Boston Symphony, Read conducting.

David Diamond

David Diamond (1915-2005) was considered one of the preeminent American composers of his generation. His works are frequently tonal or modally inspired, and his widely spaced harmonies give them a distinctly American flavor. He was a close personal friend of Leonard Bernstein, and he dedicated a number to him, and vice versa. Diamond’s compositional style is described as “lyrical, clear of structure, and marked by contrapuntal interest and the increasing use of chromaticism in his later compositions.” Diamond’s Quartet for Piano and String Trio in E minor was awarded the first prize in the chamber category, but the enormous success he enjoyed in the 1940s and early ’50s was “eclipsed by the dominance of atonal music… As such he became part of what some considered a forgotten generation of great American symphonists.” The initial phase of the Paderewski Fund for the Encouragement of American Composers came to an end in 1945 and 1948, with Herbert Elwell and Phyllis Hoffman taking the final awards. In the 1950s, the fund was renamed Paderewski Fund for Composers and began awarding commissions to composers in lieu of the competition.