The Franco-Prussian War, the rise of Germany, and the tangled web of European alliances all conspired to pull France into battle in 1914…and Ravel, then nearing forty, was determined to serve in the conflict despite his small stature and frail health.

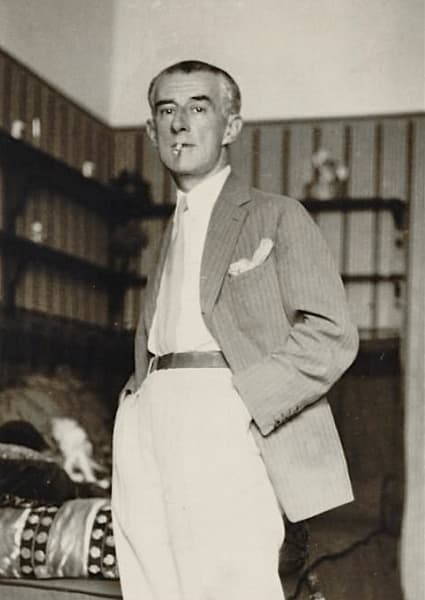

Maurice Ravel in 1916

Today, we’re looking at what he experienced and how the horror of war manifested in four of his best-known pieces.

How European Politics Sent Maurice Ravel to War

During the nineteenth century, France and Germany were competing for power and influence in Central Europe.

The Franco-Prussian War, fought between 1870 and 1871, ended in a humiliating loss for France and unification for Germany. An arms race gained speed, along with the race for cultural supremacy.

By the time Maurice Ravel was born in the spring of 1875, the French government was requiring all twenty-year-old men to serve in the military for three years.

However, in 1895, Ravel was so physically small and weak that he was rejected for “frailty.”

Fast forward two decades. In June 1914, Serbian nationalists, furious over oppression by the Austrian Empire, assassinated both Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife.

Franz Ferdinand was not minor royalty: he was the presumptive heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his death was a direct shot at the empire’s stability and continuity.

A mini documentary about the causes of World War I

At the time, European countries were bound by a number of criss-crossing alliances. Austria wanted to respond to the assassination by declaring war on Serbia, and Austria was allied with Germany.

Meanwhile, Germany’s enemy, France, reaffirmed its own alliance with Russia, agreeing to fight with Serbia against Austria.

So to sum up, one side consisted of Austria, Germany, and its allies; the other consisted of France, Russia, Serbia, and its allies.

In the aftermath of the assassination, Austria issued a draconian ultimatum to the Serbs, which was rejected. Austria responded by declaring war on Serbia, and Austria’s ally Germany dutifully followed suit.

From there, the dominos kept falling. Germany also declared war on Russia. Then, in an attempt to avoid a two-front war, Germany tried to knock its old enemy, France, out of the conflict early by invading it, so it could focus on fighting Russia instead.

The seeds of World War I were rapidly sprouting.

The Race to Finish the A-Minor Piano Trio

Maurice Ravel

Ravel spent much of 1914 working on his piano trio in A-minor.

As the international situation deteriorated that summer and disaster appeared increasingly inevitable, he was struck by a new sense of urgency. He wrote in early August 1914, “I am working on the Trio with the sureness and lucidity of a madman.”

He told Stravinsky, “I have never worked with more insane, more heroic intensity.”

He intended to join the military to defend his homeland, and he was well aware he might not survive to see the piece’s premiere.

Working madly, he finished the trio – his potential musical epitaph – by the end of August. As a dark joke, he called it a “posthumous work.”

The War Begins

Maurice Ravel in 1916

On 1 August 1914, an order for the mobilisation of French troops was issued, triggering the activation of three million French reservists between the ages of 24 and 38.

A quirk of the calendar meant that Maurice Ravel fell just outside that age limit (he had turned 39 in March).

He tried to enlist by joining the French Air Force, believing that his stature would prove handy in the small cockpits of early airplanes, but he was turned down due to his age, weight, and minor heart trouble.

It’s important to remember that aviation technology was in its infancy and deeply dangerous. According to one analysis, the average life expectancy of Canadian fighter pilots during the Great War was around eleven days. In effect, Ravel was volunteering for a suicide mission. Music lovers are lucky he was rejected for the job.

Instead of flying, Ravel decided to contribute to the war effort by volunteering on the home front, assisting wounded soldiers in Saint-Jean-de-Luz on the Bay of Biscay, just across the river from his birthplace, Ciboure.

Ravel Becomes a Military Driver

However, Ravel quickly came up with another plan.

Maurice’s engineer brother Edouard was serving as a military driver, and Maurice – always interested in the inner workings of machinery – found himself attracted to the idea of following in his brother’s footsteps. Maurice began taking daily driving lessons.

Finally, in March 1915, the month of his fortieth birthday, he joined the Army as a truck driver with the 13th Artillery Regiment.

Stravinsky noted, “At his age and with his name, he could have had an easier place, or done nothing.”

For about a year, Ravel was stationed in Paris repairing military vehicles, writing that this was “time spent being busy not doing very much.”

But in March 1916, he was sent to the front lines during the eleven-month-long battle of Verdun, which claimed an average of 70,000 lives a month.

Ravel’s job was to deliver supplies to the front, especially petrol. His truck (which he nicknamed Adélaïde) would often be loaded down with twice the recommended amount of cargo.

Ravel usually drove at night to avoid being seen. During the winter months, he had to wear a fur coat to have a hope of staying warm.

Ravel: Blacklisted?

In between all this, he remained in contact with what remnants of musical Paris were still active.

In 1916, a group of musicians headed by Vincent d’Indy, Théodore Dubois, and Camille Saint-Saëns founded the Ligue Nationale pour la Défense de la Musique Française (National League for the Defense of French Music).

D’Indy wrote that he wanted French music to “liberate itself from the German musical domination.” The group of influential musicians proposed blacklisting German and Austrian composers from concert programs.

This idea sat poorly with Ravel. In June 1916, he wrote to the group:

“I do not believe that to safeguard our national artistic heritage we must forbid performing German and Austrian works… It would even be dangerous for French composers to ignore systematically the works of their foreign colleagues, and form a sort of national coterie: our musical art, so rich at present, would soon degenerate, locking itself into stale formulas.”

Due to this stance, his own music – arguably the most recognisably French of its generation – was briefly blacklisted in certain Parisian music circles.

Wartime Illness and Grief

Maurice Ravel in uniform

Understandably, Ravel’s physical and mental health deteriorated over the course of the year.

Six months into his time at the front, he developed dysentery. He was forced to go on medical leave between October 1916 and January 1917.

Tragedy compounded in January 1917 when his beloved mother passed away.

The loss shattered him, especially on the heels of the deaths of so many of his friends and acquaintances in the trenches.

Pianist Marguerite Long (who had lost her own husband in the war) observed that Ravel was “depressed, thin, and suffering from neurasthenia.”

Due to his age and poor health, Ravel was discharged in June 1917. His dream – or nightmare – of military service was over.

In April 1914, Ravel had begun Le Tombeau de Couperin, a suite for solo piano inspired by the work of French Baroque composer François Couperin.

Between 1915 and 1917, Ravel contributed bits and pieces to the score, but he only finished it after his discharge in 1917.

In the face of the losses of war, the work’s concept had taken on a deeper, more personal meaning.

Instead of celebrating French nationalism generally, Ravel dedicated each movement to specific dead friends. (The final movement was dedicated to Captain Joseph de Marliave, a musicologist and husband of pianist Marguerite Long, who gave the work’s premiere.)

Marguerite Long

These meditative pieces were light, airy, and beautifully constructed, with not a single extraneous note.

Ravel famously explained why he hadn’t written a more overtly tragic work: “The dead are sad enough in their eternal silence.”

The peerless elegance of the French tradition would serve as his friends’ musical epitaph.

The Lasting Impact of the War on Ravel

Maurice Ravel

Even after the Armistice was signed in November 1918, Ravel’s wartime experience continued to echo in his music.

Between 1919 and 1920, he wrote the dazzling ballet La Valse, which he described as “a sort of apotheosis of the Viennese waltz.”

What better way to process the destruction of the European order than by writing a waltz in which Austria’s national dance tears itself apart?

Ravel himself disavowed any connection between the war and La Valse, but many others read it differently.

Later, in 1930, he wrote a Piano Concerto for the Left Hand for Paul Wittgenstein, an Austrian pianist who had lost his right arm in the war.

Put another way, just thirteen years after delivering munitions to the front, France’s leading composer wrote a piano concerto for a great Austrian pianist…who could have been hit by those same munitions.

It was a striking finale to Maurice Ravel’s tragic, traumatic, and deeply influential military service.

No comments:

Post a Comment