It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Sunday, March 31, 2024

Stravinsky: The Firebird / Petrenko · Berliner Philharmoniker

Friday, March 29, 2024

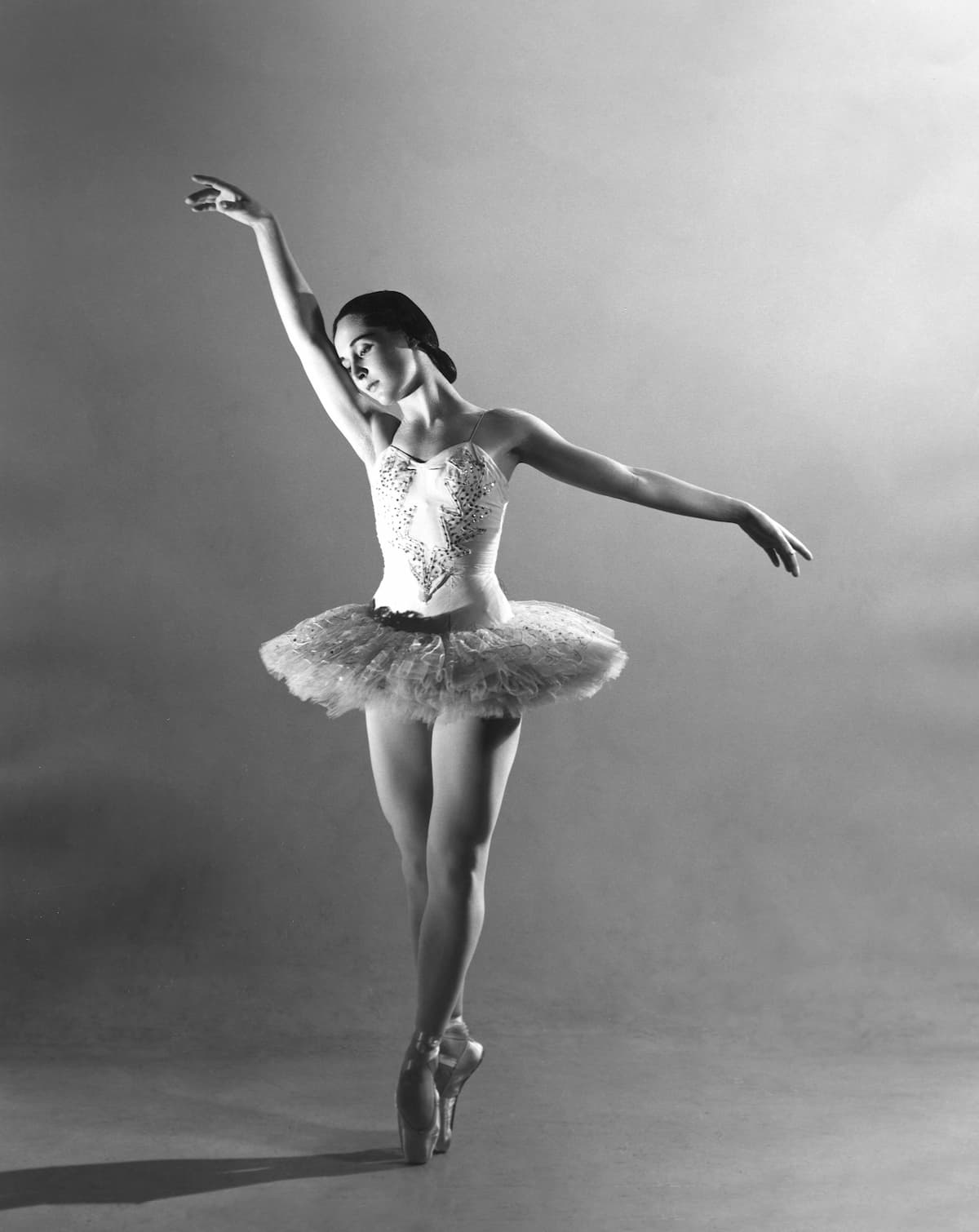

Dancing Bach’s St Matthew Passion

by Georg Predota, Interlude

Bach’s St. Matthew Passion

In both works, the text is capable of telling the story all on its own, but Bach adds multiple layers of musical meaning that make it possible to enjoy the music on a number of levels. Bach’s music makes the text and the story come alive, and the compositional complexity and theological depth trigger a wide range of profound emotional responses.

As the Passions are sacred oratorios performed in churches and concert halls, they forgo some important visual elements associated with opera. There are no costumes or scenery, and there is no action. So what happens when one of the single greatest masterpieces of Western sacred music combines Bach’s powerful music and the passion narrative with spellbinding dance performances?John Neumeier

John Neumeier

Transforming the gospel into dance and expressing religious experiences and convictions, has been the life work of the American ballet dancer, choreographer, and director John Neumeier. After a career as a ballet dancer in the United States, Neumeier became director of the Frankfurt Ballet, and subsequently the chief choreographer at the Hamburg Ballet in 1973. He has choreographed more than 170 works, including many evening-length narrative ballets.

John Neumeier’s St. Matthew Passion

Neumeier premiered his St Matthew Passion as a medieval passion play in a Hamburg church before taking it to the Hamburg Opera House. Neumeier’s dancers, dressed in white, embody Bach’s human Passion, with the audience invited to physically and spiritually experience the drama of struggle and redemption. Each dancer expresses grief, doubt, and even aggression, which adds a powerful visual dimension and physical reality to the allegory. Neumeier focuses on the awe-inspiring complexity and universal appeal of Bach’s St Matthew Passion into a profoundly moving experience.

Friederike Rademann

The German choral conductor and teacher Helmuth Rilling is best known for his performances of the music of Johann Sebastian Bach and his contemporaries. He was the first conductor to have twice prepared and recorded the complete choral works of J. S. Bach on modern instruments. Rilling was a student of Leonard Bernstein in New York, and in 1954 he founded the internationally recognized Gächinger Kantorei, which joined forces with the Bach Collegium Stuttgart.

The Gächinger Kantorei is still the ensemble of the International Bach Academy in Stuttgart, and it currently combines a baroque orchestra and a selected number of choristers. The ensemble is under the direction of Hans-Christoph Rademann, and his wife Friederike was a solo dancer at the Semperoper in Dresden. She has devoted herself to expressive dance and developed choreographies for a number of works by Chopin, Ravel, Schumann, and Bach, including the St. Matthew Passion. Her choreography includes the participation of one hundred schoolchildren, who connect and experience Bach’s monumental work as an artistic form of self-expression.

Gloria Contreras

Gloria Contreras

Born in Mexico City, the dancer and choreographer Gloria Contreras was a student of George Balanchine. She taught choreography at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México and was director and founder of its choreography workshop. For Contreras, dancing was much more than just a profession, it is “a way of life that teaches a greater understanding of life itself.” Contreras adopted the neo-classical choreographic style of Balanchine, and utilized the music of Mexican composers in her work. However, she also left us a moving choreography of the St Matthew Passion.

Kamea Dance Company

The Passion settings of Bach continue to inspire contemporary ballet productions. One such interpretation, combining music with virtuosic dance movements, comes from the Kamea Dance Company from Be’er Sheva, in southern Israel and the choreographer Tamir Ginz. The title “Matthew Passion 2727” asks the question of what will have happened to this work 1000 years after its premiere in 1727, and what will happen on the way there. Ginz does not translate doctrines, world views, or political statements, but expresses universal human experiences such as suffering and envy, grief and betrayal.

Thursday, March 28, 2024

88 Minutes of Piano Excellence for World Piano Day 2024 #PianoDay2024

Parsifal - Karfreitagszauber - Good Friday Music - Wagner - Kempe

Hindemith: Symphony in B-flat

Tuesday, March 26, 2024

“Tell Him” / "And I'm Telling You I'm Not Going"

Mendelssohn: 3. Sinfonie (»Schottische«) ∙ hr-Sinfonieorchester ∙

Sunday, March 24, 2024

Traumhafte Version von Claude Debussys "Claire de Lune"

The Godfather - Main Title (The Godfather Waltz) - HQ - Nino Rota

Bravo! Italian Embassy brings a night of opera to Tondo’s youth

CULTURAL EXPOSURE More than 600 students and residents of Tondo district in Manila gather at the covered court of SanPablo Apostol Parish Church on Saturday night to experience Italian culture through the staging of Giacomo Puccini’s one-act opera “Gianni Schicchi,” performed by members of the Manila Symphony Orchestra. —PHOTOS BY RICHARD A. REYES

By: Jane Bautista - Reporter / @janebautistaINQ

Philippine Daily Inquirer / 05:40 AM March 25, 2024

The Italian Embassy’s “social experiment” of introducing Italian opera to children and adolescents in Tondo, Manila, had turned out to be not just a learning experience for the young audience but also a night of entertainment last Saturday night.

“My favorite part was when [the characters] were scrambling to find their names in the will for their inheritance,” said 9-year-old Dhenvey, who was among the audience regaled by Giacomo Puccini’s one-act opera “Gianni Schicchi,” as performed by members of the Manila Symphony Orchestra (MSO) at San Pablo Apostol Parish Church on Velasquez Street.

“Gianni Schicchi” revolves around the story of the Donati family which seeks to change the will of their deceased aristocrat relative Buoso Donati to inherit his fortune. They enlist a peasant, Gianni Schicchi, to impersonate Buoso so they can dictate a new will.

Opera, the genre of musical theater that began in Italy in the late 16th century, had its audience in the country during the colonial era until the American rule, and continued to thrive past the postwar era with various efforts to promote the genre to a wider audience.

In a roundtable meeting with Inquirer editors and reporters earlier this month, Italian Ambassador Marco Clemente cited the embassy’s support behind a double-bill Puccini performance at Hyundai Hall at Areté in Ateneo de Manila University on March 16 and March 17.

The event served as a fundraising drive for the foundation bearing the name of the MSO, a pioneering orchestra in the country founded in 1926 by Austrian-Filipino conductor and pianist Alexander Lippay.

‘Bring music to everyone’

Clemente said the embassy opted to bring opera to Tondo’s youth because they didn’t want the young audience to feel intimidated in a setting outside their community.

“Gianni Schicchi” was performed before an audience of 620 students between Grade 5 and college, all scholars of the Canossa-Tondo Children’s Foundation Inc. (CTCFI).

MSO conductor Marlon Chen said that as performers, “we want to bring music to everyone.”

“That’s why the orchestra is called the symphony for the people, so we’re always up to the task no matter where we are … It was challenging but we adjust, that’s what we do,” Chen said in a brief interview after the one-hour show.

Throughout the performance, there were short pauses to explain to the audience what would happen in an upcoming scene in the opera.

Since the songs were in Italian, the scenes were broken up, so to speak, to keep the audience “up to date,” Chen said.

Before the first scene, for example, two of the performers first explained to the young audience the simple meaning of opera, being essentially a drama set to music—“musika at istorya.”

The children, as if taking part in a classroom exercise, were instructed to repeat the two words, when asked: “Could you remind us once more of the definition of an opera?”

During the scene where members of the Donati family were searching for Buoso’s last will, the actors went down the stage to mingle with the audience, asking the kids if they saw the document.

Dhenvey, along with his friends Dylan, 11, and Janno, 8, who were seated behind this reporter, appeared to be deeply engaged in the story, with one of them even explaining what was happening to his seatmates as the scenes unfolded.

After the show, Dhenvey said in an interview that he actually knew the plot because he was one of the few kids selected to watch the Ateneo performance.

“We were amazed by [the actors’] voices,” the boy said, adding that unlike in the Tondo performance where the scenes were briefly explained by the actors, the Ateneo show had subtitles instead.

‘Very enthusiastic’

In his keynote speech during the event, Clemente described the Tondo performance—one of nine events organized by the embassy as part of a cultural festival—as “historical [since this was] the first time that we bring Italian classical music, [a] fully staged opera, on this stage.”

“Tondo is very close to the Italian Embassy,” Clemente told the audience. “There’s this special bond that unites you and the Italian Embassy.”

Sought for comment about this endeavor to bring opera in Tondo, poet and journalist Pablo Tariman said, “Thus far, [there is] no history of opera being staged in Tondo. But it is possible that opera thrived in Teatro de Tondo in 1841. But not documented.”

Tariman said further research was needed, but he cited early theaters in Manila during the Spanish to American periods such as the Teatro Lírico, Teatro Español and Teatro del Principe Alfonso.

Marco Clemente

He said opera these days could be staged anywhere and not necessarily in a regular opera house, as he noted, for example, initiatives of the opera group of Viva Voce under soprano Camille Lopez Molina, who staged operas in a Baguio restaurant in 2015.

He recalled that before the Cultural Center of the Philippines was closed for renovation, the Italian Embassy, in partnership with the Department of Education, invited students to watch a performance of Puccini’s “Turandot.”

“They were very enthusiastic. Exposure of students to opera will bring about a new generation of audiences for the art form,” said Tariman, a veteran of media reporting on the arts, who is coming out with his second book, “Encounters in the Arts,” in May.

“As of now, the opera is identified with senior citizens and that is because the young people think opera is not enjoyable compared to what they get from pop music. But once given the opportunity to watch it, opera is [a] big deal among young people,” he added.

‘Dignity and honor’

Italian priest Giovanni Gentilin, vice president of CTCFI, said that in his more than three decades of service to the community in Tondo, it was his first time to see people in the music field of orchestras reach out to young people, “especially those in difficult situations,” and share a part of Italian culture with them.

According to him, the event offered “more dignity and honor to the community where the Canossian fathers are serving.”

CTCFI managing director Teresita Carmelo said she hoped the opera would serve as an “inspiration” for the children in their community.

Saturday, March 23, 2024

Anne-Sophie Mutter, Daniel Barenboim, Yo-Yo Ma – Beethoven: Triple Concert

Friday, March 22, 2024

Orpheum Madams - It Don't Mean A Thing

Berlioz: Hungarian March from La damnation de Faust

Composer Galina Ustvolskaya: The Shostakovich-Trained Iconoclast

By Emily E. Hogstadt, Interlude

Galina Ustvolskaya and her dog

But she was so much more than this. She was also fiercely independent, staggeringly talented, and completely unafraid. She not only refused to fit in a musical mold but threw out that mold entirely.

Today, we’re taking a look at the life and times of Soviet composer Galina Ustvolskaya.

Ustvolskaya’s Childhood

Galina Ustvolskaya was born on 17 June 1919 in Petrograd to an unmusical family. Her father was a lawyer, and her mother was a teacher from impoverished nobility.

Her childhood was lonely and full of financial pressures.

“I would wear an old coat of my father’s (which was too long for me) and his muffler, which I gave to a young friend. I loved to give gifts, although we did not have anything to spare. Since childhood, I could not tolerate these kinds of pressures.”

Her desire for financial security would later impact her career choices.

She loved music deeply from an early age. When she was young, her parents took her to a performance of Tchaikovsky’s opera Eugene Onegin, but the family had to leave when she started crying. “I want to be an orchestra,” she told them.

Time with Shostakovich

Ustvolskaya studied at a school for young people associated with the Leningrad Conservatory. In 1939, when she turned twenty, she joined Dmitri Shostakovich’s composition class. That year, she was the only woman in that class.

Shostakovich was intrigued by her and in awe of her talent. “I am convinced that the music of G. I. Ustvolskaya will achieve world fame and be valued by all who hold truth to be the essential element of music,” he wrote once. He also said, “It is not you who are under my influence, but I who am under yours.”

He valued her opinion so much that he asked for her feedback on his own compositions. He also used a theme from her clarinet trio in his fifth string quartet (from 1952) and his Suite on Verses of Michelangelo Buonarroti (from 1974, toward the very end of his life).

Ustvolskaya studied in his class twice – once from 1939 to 1941 and again from 1947 to 1948. That six-year break coincided with the war, as well as the devastating two-and-a-half-year siege of Leningrad.

A month into the siege of Leningrad, Shostakovich was evacuated to Moscow and Ustvolskaya to Tashkent, the current-day capital of Uzbekistan, along with others linked to the Conservatory. In 1943, she worked in a hospital in the city of Tikhvin, two hundred kilometers from St. Petersburg.

Galina Ustvolskaya

She later made it very clear that she was not keen on an association with Shostakovich. She called his music “dry and lifeless” and wrote to her publisher, “One thing remains as clear as day: a seemingly eminent figure such as Shostakovich, to me, is not eminent at all, on the contrary, he burdened my life and killed my best feelings.”

Her distaste for him may have been rooted in extra-musical reasons. She later claimed that Shostakovich proposed marriage to her, but she turned him down.

Later, she went even further: “There is no link whatsoever between my music and that of any other composer, living or dead,” she once proclaimed.

Ustvolskaya and Soviet Propaganda

From 1947 to 1977, she taught composition at the Leningrad Conservatory. She didn’t think of herself as a particularly talented professor – composition was her true calling – but teaching was a way to make a living.

In February 1948, a resolution went out from the Soviet government, accusing some composers of Formalism (i.e., failing to compose music that fully supported the state).

After this, she split her creative self into two parts. One composed propaganda pieces acceptable to Soviet leadership, while the other wrote secret avant-garde works that she knew might never be heard.

Writing music to please the authorities was soul-destroying, but she was apparently very good at it. Her tone poem Stepan Razin’s Dream opened the Leningrad Philharmonic’s 1949 season, to acclaim. She was even nominated for the Stalin Prize.

However, in 1962, she hit her limit. From that time on, she vowed to only write what she truly wanted to write, and she worked to destroy all traces of everything she ever wrote for political reasons.

Fortunately, later in the century, the Soviet Union started being easier on modernist composers, and allowing them to share some of their more controversial music. Ustvolskaya slowly began sharing some of the music she’d been keeping hidden.

Ustvolskaya’s Later Years

Galina Ustvolskaya

By the 1970s the Leningrad Union of Composers began presenting evenings of her music, and critics were impressed.

Her music has several distinguishing features, including extreme dynamics, unusual instrumentation, and brutal and relentless repetition.

The website Ustvolskaya.org writes, “Ustvolskaya’s music is unique, unlike anything else; it is exceedingly expressive, brave, austere, and full of tragic pathos achieved through the most modest of expressive means.”

Unfortunately, for years, hardly anybody outside the Soviet Union heard it. But in 1989 her work was performed at the Holland Festival, and it made a big impression on audiences.

She was living as a bit of a hermit by the 1990s, but she traveled to Amsterdam to watch performances of her work. Although she hated interviews, she agreed to one with journalist Thea Derk. But when the time for the interview came, she nearly backed out, and only agreed to partake after she was assured she could answer questions with monosyllables, without elaboration. (Luckily, Derk was able to get more than that out of her.)

She was asked how she liked the performance she’d heard. “Not very much,” she said bluntly. She elaborated: “The acoustics were not favourable, so that the piano didn’t come out properly, and the five double basses should have been placed more to the front. Moreover, the ensemble, recruited more or less ad hoc from members of the Concertgebouw orchestra, hadn’t as yet properly mastered the score, and the reciter wasn’t adequately amplified. But yesterday it was better and I hope it will again be better tonight.”

Ustvolskaya’s Death and Legacy

A perfectionist iconoclast to the end, Galina Ustvolskaya died in 2006 in St. Petersburg. She was eighty-seven years old.

In 1998 she gave a description of her life to an interviewer that serves as a kind of thesis statement about her music:

“The works written by me were often hidden for long periods. But then if they did not satisfy me, I destroyed them. I do not have drafts; I compose at the table, without an instrument. Everything is thought out with such care that it only needs to be written down. I’m always in my thoughts. I spend the nights thinking as well, and therefore do not have time to relax. Thoughts gnaw me. My world possesses me completely, and I understand everything in my own way. I hear, I see, and I act differently from others. I just live my lonely life.”