by

A jaw-dropping collection of technically dazzling fugues, stopped mid-measure, annotated by a poignant note from a grieving son.

Two delicate mazurkas that the composer was too sick to play and never heard performed.

A cantata for the freemasons.

A standard string quartet movement requested by a publisher to replace a masterpiece finale.

A song about a carrier pigeon.

These are descriptions of the final works of the most famous composers in classical music history. Composers rarely choose which piece will be the last one in their output. As a result, the stories behind all of them are varied – and very fascinating.

Bach’s Final Work: Art of Fugue

3D portrait of J.S. Bach by Hadi Karimi

The most famous final work in classical music history is probably Bach’s Art of Fugue, a set of pieces written for an unknown instrument.

But was it really Bach’s last work? The apparently final fugue in Art of Fugue is known as the “Fuga a 3 Soggetti” (or, in English, the “Fugue in Three Subjects”). Its manuscript famously ends in the middle of measure 239, as if Bach went off to dinner and never came back.

At the end of the aborted fugue, there’s a note in the handwriting of Bach’s son, composer Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, that reads: “While working on this fugue, which introduces the name BACH in the countersubject, the composer died.”

However, scholars have pointed out that Bach endured a period of failing health before his death, including severe vision trouble that would have precluded his writing out this fugue. It seems more likely that the fugue dates back slightly earlier, to a year or two before his death.

Regardless of whether this was in fact Bach’s final work or not, it has entered classical music lore as such. And who are we to get in the way of a good story?

Mozart’s Final Work: Little Masonic Cantata

Mozart’s death mask

Thanks to the movie Amadeus, pop culture would have us believe that Mozart’s final piece was his Requiem. Mozart was indeed working on the Requiem upon his death in early December 1791, but his final completed work was actually a piece called the Little Masonic Cantata, written to celebrate the opening of the temple of the New Crowned Hope Lodge in Vienna. It premiered on 17 November 1791. Conducting that premiere would mark Mozart’s last public appearance as a musician.

Mozart monument in Vienna

This cantata creates a somewhat unusual sound palette, in that it was written for male choir and three tenor soloists, so it sounds very different from other works that Mozart wrote.

Beethoven’s Final Work: String Quartet No. 16

Beethoven on his deathbed

“What was the last music Beethoven composed?” you ask. There are two potential answers to that question.

The final work that he actually finished was his sixteenth string quartet, which was eventually published as his op. 135. It was completed in October 1826, five months before Beethoven died.

Beethoven’s Op. 130 “Große Fuge”

However, the final music that he wrote was the final movement of his thirteenth string quartet Op. 130, which he composed in November 1826. Beethoven’s publisher was not a fan of the original finale to the thirteenth quartet, claiming that it was too long, too demanding, and generally indecipherable. In response, Beethoven reluctantly tossed off a replacement finale. This replacement finale was added to the quartet, and the indecipherable monster movement was published separately as the Grosse Fuge.

(Another work that could conceivably be added to this list is Beethoven’s tenth symphony, which was completed in 2021 by artificial intelligence, based on Beethoven’ surviving notes.)

Schubert’s Final Work: “Die Taubenpost”

Grave of Franz Schubert at at Central Cemetery Wiener Zentralfriedhof

We don’t know for sure what Schubert’s final piece of music was, but the most frequently cited candidate is the song “Die Taubenpost” (“The Pigeon Post”). The text by poet Johann Gabriel Seidl describes the speaker’s carrier pigeon, who has been entrusted with an important message for a lover. At the end of the poem, the pigeon’s name and symbolic identity are revealed:

Her name is – Longing! Do you know her?

The messenger of constancy.

“Die Taubenpost” was published after Schubert’s death in a fourteen-song collection assembled by publisher Tobias Haslinger. Haslinger dubbed the collection “Schwanengesang” (Swan Song). It’s unlikely that Schubert actually intended for these songs to be published together, but of course the “swan song” theme of the collection suggested itself after Schubert’s untimely death.

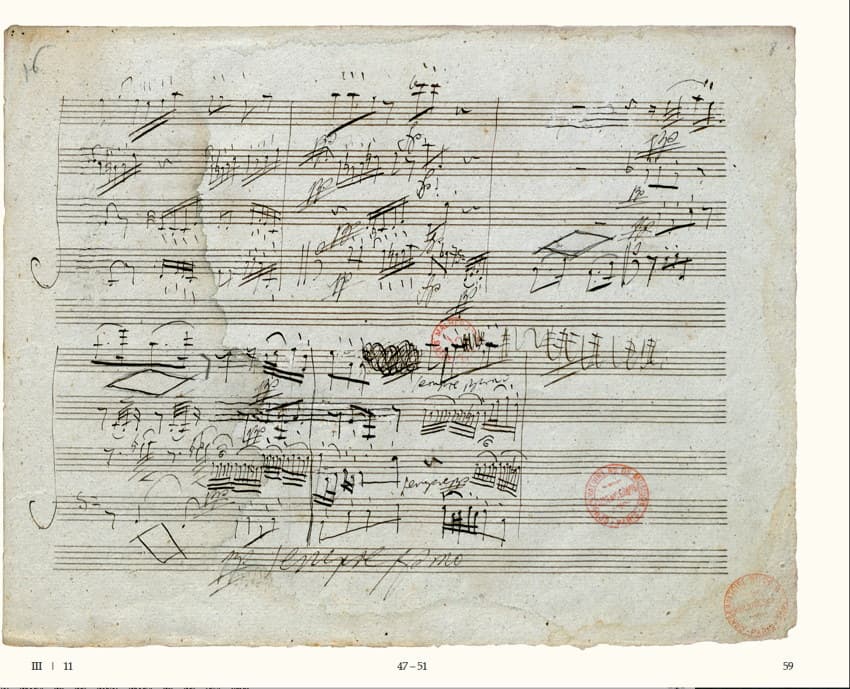

Chopin’s Final Works: “Mazurka in G Minor, Op. 67, No. 2” and “Mazurka in F minor, Op. 68, No. 4”

Chopin’s death mask © Wikipedia

When Chopin was on his deathbed in 1849, he asked that all of his music not yet assigned opus numbers be burned. Luckily for music lovers, after Chopin died in October, his mother and his sisters decided to veto his request. A Chopin friend named Julian Fontana selected a variety of manuscripts from Chopin’s papers and published them in 1855.

Chopin on his deathbed

Among them are what are believed to be Chopin’s last two compositions: the “Mazurka in G Minor, Op. 67, No. 2” and the “Mazurka in F minor, Op. 68, No. 4.” According to legend, Chopin never actually heard these last works, as he was too weak to leave his bed to play. They are both dreamy, haunting, devastating works: a quiet sendoff from an ever-elegant composer.

No comments:

Post a Comment