It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Friday, December 19, 2025

25 Beautiful Classical Pieces That Relax Your Soul and Heart 🎼 .

Dance, Dance, Dance: The Baroque Dance Suite

by ,Maureen Buja

In the new series on dance music, Dance, Dance, Dance, we’ll be looking at dance and how it comes into classical music. You’re going to be surprised at some of the places where it has made an appearance.

We’ll start with not the oldest dances, but with some of the most familiar. In the Baroque era, the dance suite was one of the most popular forms of instrumental music. Pairing of dances was common in the medieval period, but it wasn’t until the 17th century that the keyboard virtuoso Johann Jakob Froberger codified the movements of the suite to include four specific dances: the Allemande, the Courante, the Sarabande, and the Gigue.

Each dance came from a different country and had a different tempo and time signature so that along with the variety of country styles, each dance had its own character.

As its name indicates, the Allemande comes from Germany. It started as a moderate duple-meter dance but came to be one of the most stylized of the Baroque dances. In its earliest versions it was simply called ‘Teutschertanz’ or ‘Dantz’ in Germany and ‘bal todescho’, ‘bal francese’ and ‘tedesco’ in Italy.

Guillaume: Allemande, 1770

It is often paired with a following Courante (from France). When the Allemande was a dance, it was performed by dancers in a line of couples who took hands and then walked the length of the room, walking 3 steps and then balancing on one foot. Musically, the allemande could be quite slow, such as in this piece by Johann Jakob Froberger. Since it was originally intended as a walking piece, the tempo is understandable.

As the century went on, however, the Allemande became faster and eventually functioned like prelude, exploring changing harmonies and moving through dissonances.

In England, the Allemande, or, as it was known there, the Almain or Almand, also became a part of the repertoire. Although this example is short, it could have been repeated multiple times.

By the 18th century, the allemande could get to be quite lively. It has gotten disassociated with its dance and exists solely as a musical form.

In the Baroque suite, the Allemande was followed by the contrasting Courante (from France). The name, derived from the French word for ‘running,’ is a fast dance, performed with running and jumping steps. Following the Allemande in duple meter, the Courente was in triple meter.

In his 17th-century collection Terpsichore, German composer Michael Praetorius collected 312 pieces of dance music, for 3-5 unspecified players. This collection of French dances brought together music of the latest fashion, ‘as played and danced in France’ and that was ‘used at princely banquets or particular entertainments for recreation and enjoyment’. The three courantes here show the different ways one style could be changed.

J.S. Bach used Allemande / Courante pairs in his Partitas and we can hear again that the tempos are contrasting, but really too fast for dancing.

The next dance in the Baroque Suite came from Spain, the Sarabande. It started as a sung dance in Spain and Latin America in the 16th century and by the 17th century, was part of the Spanish guitar repertoire. The Spanish line of development means that it also had Arab influences. As a dance, it was usually created by a double line of couples who played castanets. Once the sarabande got to France, however, what had begun as a fiery couples’ dance changed character completely. It slowed in time, and gradually became a work that might be described as the intellectual core of the Baroque suite.

Fritz Bergen: The Sarabande, 1899

And in a more stately manner:

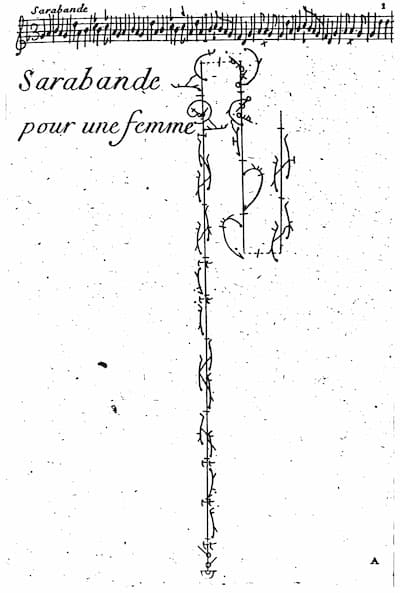

Feuillet and Pécourt: Recüeil de dances: Women’s steps for the beginning of the Sarabande, 1704

The final element of the Baroque dance suite was the English Gigue (or jig). This was a fast dance in 6/8 time that was paired with the slower sarabande. Jigs have been known since the 15th century in England, but as it reached the continent in the 17th, is divided into distinct French and Italian versions. The French gigue was moderately fast with irregular phrases.

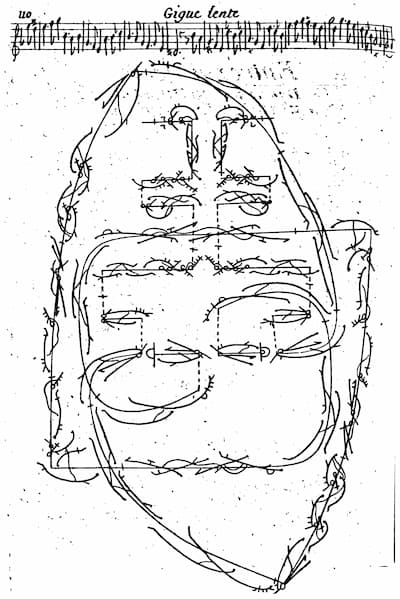

In Feuillet’s and Pécourt’s early 18th century collection, they present the choreography as used in various ballets, mostly by Lully. Here is the middle section of a slow gigue. The two dances start in the center and then move in opposite directions, starting with a large irregularly shaped circling around each other.

Feuillet and Pécourt: Recüeil de dances: Men’s and Women’s steps for the Gigue Lente, 1704

The Italian giga, although it sounded faster than the French gigue, actually had a slower harmonic rhythm. It also didn’t have the irregular phrases of the French model.

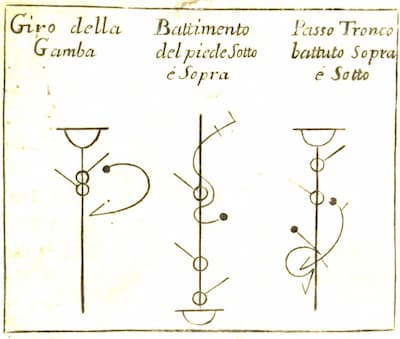

When dances were the social entertainment, there was an enormous business in traveling dancing masters teaching the latest steps, and books published to show how to perform them. This early 18th-century book shows your foot positions, where you turn your leg, where you beat your foot, and bend your knee while your leg is in the air.

Dufort: Trattato el ballo nobile, 1728

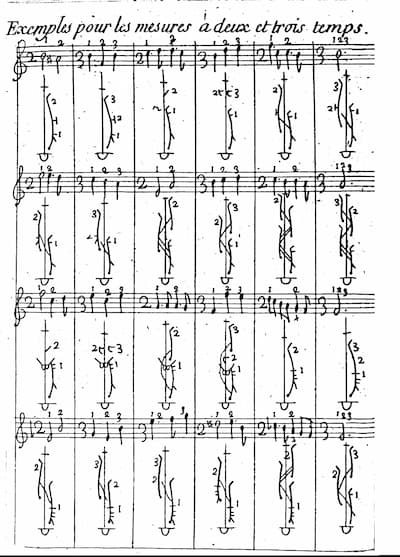

In this more elaborate image from Raoul-Auger Feuillet and Guillaume Louis Pécourt’s 1704 book Recüeil de dances, they give examples of foot movements based on the musical rhythm.

Feuillet and Pécourt: Recüeil de dances, 1704

By the 18th century, the dancing manuals were decrying the introduction of ballet steps onto the dance floor. One 1818 manual asks that dancers be more aware of what they are doing: ‘The chaste minuet is banished; and, in place of dignity and grace, we behold strange wheelings upon one leg, stretching out the other till our eye meets the garter; and a variety of endless contortions, fitter for the zenana of an eastern satrap, or the gardens of Mahomet, than the ball-room of an Englishwoman of quality and virtue.’ In 1875, an American dance manual starts out with the plain declaration that ‘The dance of society, as at present practiced, is essentially different from that of the theatre, and it is proper that it should be so. The former, consisting of movements at once easy, natural, modest and graceful, affords an exercise sufficiently agreeable to render it conducive to health and pleasure. The latter…requires in its classic poses, poetical movement, and almost supernatural strength and agility, too much study and strain…to admit of its performance off the stage…’

As these dance works entered the instrumental repertoire and took to the concert stage versus the dance floor, they became disassociated from their dances – their tempos changed so as to be undanceable and it is the contrast between movements that become the focus: duple or triple meter? Fast or slow tempo? In the next parts we will look at other dance movements, some from the Baroque and others more familiar from the Classical and Romantic repertoire.

The Most Memorable Composer Christmases: Mahler, Rachmaninoff, and More

by Emily E. Hogsta

Everyone approaches the winter holidays differently: some people feel excitement, while others feel dread. It can be a season of celebration, crushing loneliness, and everything in between.

The great composers also experienced a wide variety of Christmas celebrations. Today, we’re looking at five memorable Christmases from the lives of five great composers. (Read Part 1 here: The Most Memorable Composer Christmases: Chopin, Schumann, and More)

Mahler’s Devastating Breakup – 1884

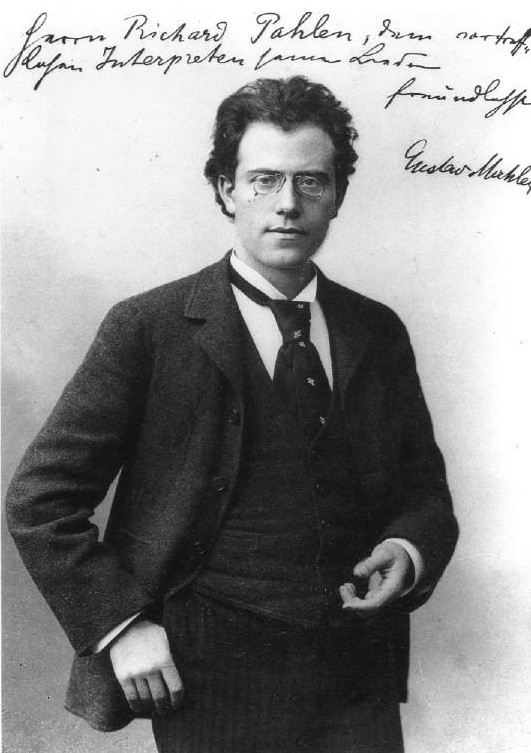

Gustav Mahler

In mid-1883, 23-year-old Gustav Mahler took a job conducting opera at the Königliches Theater in Kassel, Germany.

While there, he began working with 25-year-old coloratura soprano Johanna Richter and fell in love with her. It was his first intense love affair.

We are not sure if Richter reciprocated Mahler’s feelings quite as intensely; only one letter from her survives.

In 1884, he began composing for her, writing lyrics based on folksongs and setting them to music. He called the resulting song cycle Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, or Songs of a Wayfarer. His December 1884 was absorbed by the project.

Despite his passion for Richter, the couple was ultimately doomed.

He spent New Year’s Eve of 1884 with her and wrote to a friend about the experience:

I spent yesterday evening alone with her, both of us silently awaiting the arrival of the new year.

Her thoughts did not linger over the present, and when the clock struck midnight, and tears gushed from her eyes, I felt terrible that I, I was not allowed to dry them.

She went into the adjacent room and stood for a moment in silence at the window, and when she returned, silently weeping, a sense of inexpressible anguish had arisen between us like an everlasting partition wall, and there was nothing I could do but press her hand and leave.

As I came outside, the bells were ringing, and the solemn chorale could be heard from the tower.

Although the relationship didn’t work out, Mahler did reuse ideas from Songs of a Wayfarer in his first symphony, which he composed between 1887 and 1888. He wasn’t about to let his holiday heartbreak go to waste!

Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel Is Disappointed by the Christmas Singing of Papal Singers – 1839

Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel

Felix Mendelssohn and his sister Fanny Mendelssohn were two of the most talented child prodigies in the history of music. They remained close for their entire lives.

Felix, however, was encouraged to pursue a musical career, while Fanny’s musical accomplishments were viewed as mere feminine adornments. (Luckily, her husband understood her talent and encouraged her music-making.)

Long story short, Felix got support that she never did, and in 1830, when Fanny was 24, and Felix was 21, the family sent him on a ten-month trip to Italy…without Fanny. The trip was formative, and Fanny was fascinated by the stories of his travels.

Happily, Fanny got to go eventually. Between 1839 and 1840, Fanny, her husband, and her baby son Sebastian took their own trip to Italy, following in Felix’s footsteps.

On 1 January 1840, she wrote to her brother, sharing some observations about musical life in Rome:

We’re enjoying a pleasant life here. We have a comfortable, sunny apartment and thus far have enjoyed the nicest weather almost continuously. And since we’re in no particular hurry, we’ve been viewing the attractions of Rome at our leisure, little by little.

It’s only in the realm of music, however, that I haven’t experienced anything edifying since I’ve been in Italy.

I heard the Papal singers 3 times – once in the Sistine Chapel on the first Sunday in Advent, once in the same place on Christmas Eve, and once in St. Peter’s basilica on Christmas day – and have to report that I was astounded that the performances were far from perfect.

Right now, they seem to lack good voices and sing completely out of tune…

One can’t part with one’s trained conceptions so easily.

Church music in Germany, performed with a chorus consisting of a few hundred singers and a suitably large orchestra, assaults both the ear and the memory in such a way that, in comparison, the pair of singers here seemed quite thin in the wide expanses of St. Peter’s.

With respect to the music, a few passages stood out as particularly beautiful. On Christmas Eve, for instance, after the parts had dragged on separately for a long time, there was a lively, 4-part fugal passage in A-minor that was very nice.

I later discovered that it began precisely at the moment when the Pope entered the chapel, and I didn’t know it at the time because women, unfortunately, are placed in a section behind a grille from which they cannot see anything.

This section is far away, and in addition, the air is darkened by the smoke from candles and incense.

On the other hand, I could at least occasionally see the officials on Christmas day in St. Peter’s very well, and found them quite splendid and amusing.

We naturally had a Christmas tree, because of Sebastian, and constructed it out of cypress, myrtle, and orange branches. The branches were very lovely, but it wasn’t the best-looking tree, and Sebastian and I attempted to outdo each other the entire day in feeling homesick.

Johannes Brahms Surprises Clara Schumann – 1865

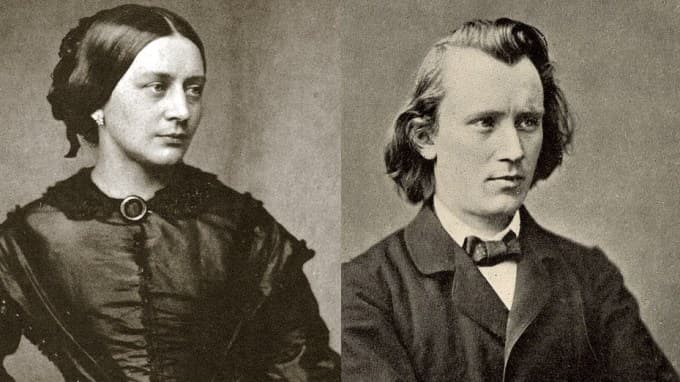

Clara Schumann and Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms and Robert Schumann’s wife, virtuoso pianist Clara Schumann, stayed close friends until the end of their lives.

They never had a traditional romance, but they loved each other deeply, and over their decades-long relationship, Brahms spent many holidays with Clara and her children.

At Christmas 1865, Johannes was 32, and Clara was 46. Both had busy performing careers that necessitated frequent travel, and Clara assumed that she wouldn’t be seeing Johannes for the holidays.

She sent him a traveling bag as a Christmas gift. With the gift, she included a letter talking about her daughter Julie, who had recently been ill.

She wrote, “Thank heaven we have fairly good news of Julie. She has got over the danger of typhoid, but it will be a long time before she has completely recovered.”

The family was worried about Julie’s health, and they didn’t even bother lighting candles on the tree that year.

But then the door opened – and Brahms appeared! He had made a seven-hour journey to Düsseldorf to surprise the family and check in on Julie himself.

Clara wrote in her diary that she was “very pleased and excited.”

Read our article about Christmas with Brahms.

Rachmaninoff Flees Russia – 1917

Kubey-Rembrandt Studios: Sergei Rachmaninoff, 1921

The Russian Revolution began in February 1917, leading to Tsar Nicholas II’s abdication in March and a provisional government taking power.

During that year’s October Revolution, a Bolshevik insurrection overthrew the provisional government. Once the Bolsheviks took power, a broader civil war broke out.

The conflict impacted Rachmaninoff’s life deeply. In the spring of 1917, he returned from touring to find that his estate had been seized by the Social Revolutionary Party. He departed, disgusted, and vowed never to return.

He and his family moved to Moscow. As tensions rose throughout the fall, he made edits to his first piano concerto with the sound of bullets flying in the background.

During this tense time, he received an invitation to give a series of recitals in Scandinavia. He accepted because it would give him and his family an excuse to flee the country.

On 22 December 1917, the Rachmaninoffs got on a train in St. Petersburg, crowded with terrified passengers who feared arrest. Fortunately, the officials who met them were kind.

The following day, they arrived at the Finnish border. To get across it, Rachmaninoff, his wife, and two daughters had to travel in an open peasant sleigh during a blizzard.

They arrived in Stockholm on Christmas Eve. Exhausted, the family stayed in their hotel.

After escaping Russia, Rachmaninoff would go on to a celebrated performing career, but he would compose less and less. Later in his life, he would remark, “I left behind my desire to compose: losing my country, I lost myself also.”

Leonard Bernstein Conducts the Historic Berlin Wall Concert – 1989

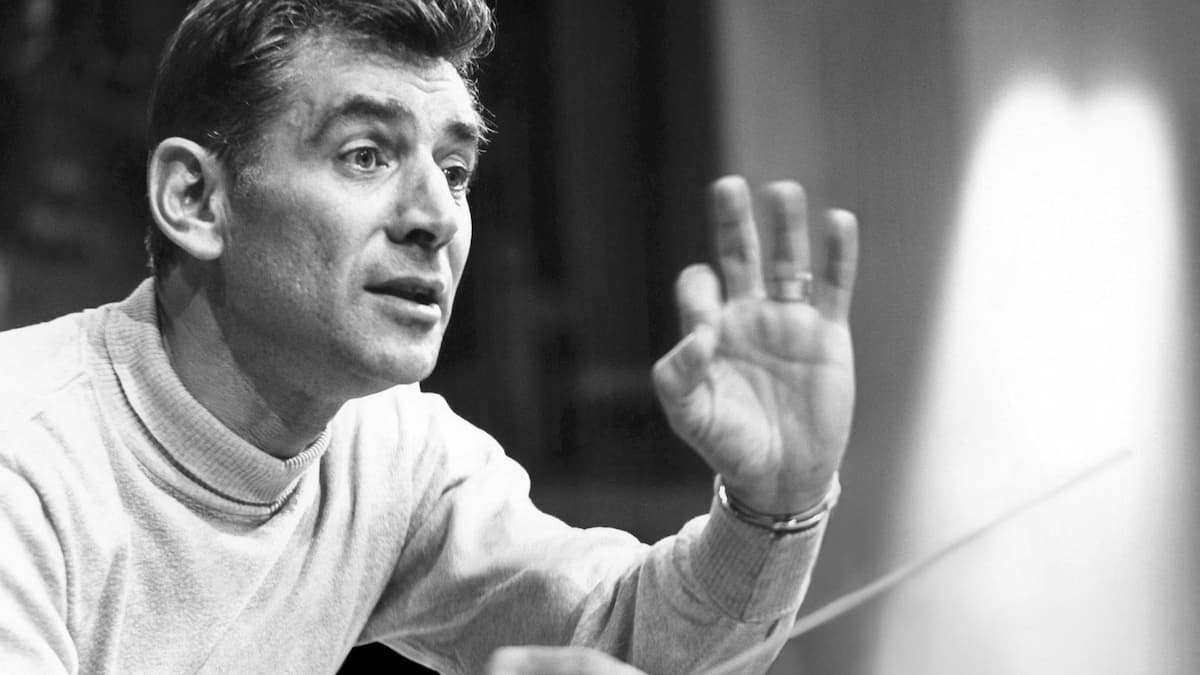

Leonard Bernstein

In November 1989, the Berlin Wall was taken down, signaling the demise of the so-called Iron Curtain that had hung across Europe for a generation.

Conductor and composer Leonard Bernstein helped to organise a performance at the present-day Konzerthaus Berlin. This venue had been burned out during World War II but was reconstructed in the late 1970s and early 1980s, opening just a few years before this concert.

Musicians from all around the world participated, including men and women from Leningrad, Dresden, New York, London, and Paris.

Together on Christmas Day 1989, they performed a concert celebrating the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Bernstein programmed Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and changed the Ode to Joy to the Ode to Freedom.

It was broadcast all over the world and became one of the most famous orchestral performances of the twentieth century, seen live by around 100 million viewers. How’s that for a memorable Christmas?

Jane Austen (Born on December 16, 1775) A Novelist with Perfect Pitch

by Georg Predota

Ask a dozen Austen-readers what makes her novels sing, and most will answer, it’s all about wit, moral clarity, and an ear for social nuance. But if you listen closer, literally, you’ll hear music threaded through her pages.

From piano practice to impromptu songs, Jane Austen’s world is full of musical moments that tell us about character, class, gender and even politics. Recent scholarship has deepened our appreciation of how Austen, an active amateur musician herself, used music as both a domestic texture and a narrative instrument.

Jane Austen

To celebrate her 250th birthday on 16 December 1775, let’s explore how Jane Austen (1775-1817) was not merely a spectator but a participant in musical life.

Sounding the Social World

Jane Austen’s engagement with classical music was both cultivated and personal, reflecting the social and cultural milieu of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Music played an essential role in her daily life, both as a form of polite entertainment and as a vehicle for emotional expression, a theme that recurs in her novels.

Music was indeed central to her daily routine. The pianoforte was the primary instrument in her circle for domestic music-making. Austen owned or had access to pianofortes like the Clementi square piano, similar to one at her Chawton home, and keyboard pieces dominated amateur performances in drawing rooms.

She practised the pianoforte most mornings before breakfast for personal enjoyment, often copying sheet music by hand. Her family’s collection of roughly 600 pieces includes works by Mozart, Haydn, and Clementi.

From Pleyel to Dibdin

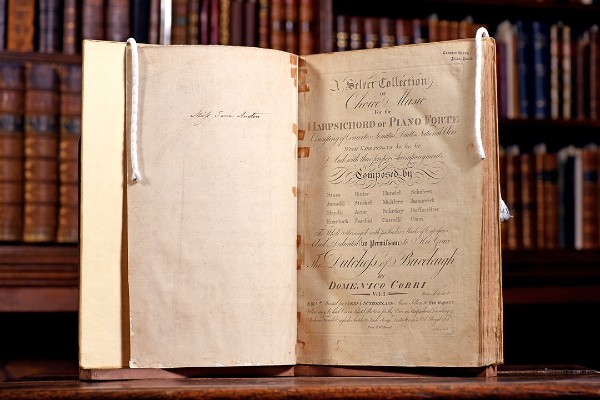

Jane Austen’s music book

Mozart overtures, Haydn adaptations, and Clementi sonatas provided a common repertoire for the evening of performance. Her favourites leaned toward contemporaries like Ignaz Pleyel, Johann Baptist Cramer, and the English theatrical composers like Dibdin and Shield. Her collection emphasised popular songs, Scottish/Irish airs, and lighter keyboard works.

These domestic music books and family collections have given scholars fresh material to link Austen’s actual repertoire with the musical references that appear in her fiction. Knowing Austen’s own musical habits makes it easier to read her fictional music as informed, sometimes affectionate, sometimes satirical commentary.

Scholars have pointed out that juvenile songs Austen enjoyed in her teens show multiple registers, including sentimentality, comic satire, and even political protest, tonalities that wryly surface again in her novels.

Ambition and Accomplishment

Jane Austen by Cassandra Austen

In Austen’s time, music was primarily a domestic art. A genteel young woman of accomplishment was expected to sing and play the pianoforte at home. Austen’s novels stage precisely these private performances.

Lucy Steele sharing a song in Sense and Sensibility; Marianne Dashwood’s pianoforte playing in Sense and Sensibility; the piano-less Fanny Price in Mansfield Park is conspicuously sidelined for social reasons.

Such moments are rarely mere background. How a character performs, what they choose to play, and who listens to all work as shorthand for taste, education, ambition and moral temperament. Recent work on class and music in Austen shows how musical accomplishment maps onto social aspiration and mobility in subtle, often ironic ways.

Gendered Expectations

Austen’s musical scenes are often gendered in telling ways. Women perform and are judged for their musical accomplishments, while men more often appear as listeners, critics, or, in some cases, as amateur players.

Scholars working at the intersection of musicology and gender studies have recently explored how Austen’s novels stage the female musical body. The nervousness of public performance, the social risk of attracting attention, and the way music can both empower and limit women in a society that prizes modest display.

New analyses argue that Austen’s attention to the embodied aspects of music, the posture at the pianoforte, voice quality, and the glance of a listener, is a realistic record of how musical behaviour operated as social grammar in the Georgian drawing room.

The Hidden Power of Music

Why should we pay attention to music in novels that are, at first glance, all about manners and marriage? Because music is a compressed language of feeling and status. Austen, who lived in a culture where a well-turned melody could signal breeding or bankruptcy of taste, used music to say what speech could not.

Reading Austen with an ear for music opens up new shades of irony and sympathy, helps explain character dynamics, and connects the fiction to the lived experience of Georgian households.

This was a world where the piano sat at the centre of private life, and where a song could be both comfort and provocation. Recent scholarship has encouraged us to hear Austen not merely as a novelist of manners but as a writer who understood the sonic textures of social life and used them with artful precision.

Saturday, December 13, 2025

Andrea Bocelli’s Magical Christmas

Friday, December 12, 2025

Best Christmas Choir Orchestra Songs 2026🎄 Best Christmas Carols 2026 🎁

🎄✨ Welcome to Night Christmas Tunes – your ultimate destination for timeless Christmas music and holiday cheer!

Here you’ll find the most beloved Christmas classics and modern festive hits – from joyful songs like Jingle Bells and Last Christmas to heartwarming carols like Silent Night and White Christmas.

🎶 Let the magic of music light up your holiday season, fill your heart with warmth, and bring festive spirit to every moment.

🎅 Night Christmas Tunes – The soundtrack of your Christmas! 🎁

The BEST Mantovani Christmas Experience performed by The New Light Symph...

Welcome to The Mantovani Experience

Step into a world where timeless melodies and cascading strings transport you back to music's golden era. We celebrate the legendary #Mantovani and his Orchestra's iconic "echoing strings" sound, faithfully recreated by The New Light Symphony Orchestra.

If you cherish the sophisticated elegance of light orchestral music—those lush arrangements that once filled concert halls and living rooms worldwide—this is your destination. Each performance captures Mantovani's signature "cascading strings" technique, that distinctive sound that made him one of the most successful orchestra leaders of all time.

Our mission is simple: preserve and share the beauty of light orchestral music with those who remember its magic and introduce it to new generations. From beloved standards to forgotten gems, we're recreating the authentic Mantovani sound with meticulous attention to every nuance.

Directed by Philip Cacayorin | Producer dedicated to vintage audio excellence

Explore our journey and production background at www.3dvinyl.com

Subscribe today and rediscover why #MantovaniAndHisOrchestra remains the gold standard of light orchestral music. Let the echoing strings wash over you once again.

The BEST Mantovani Christmas Experience performed by The New Light Symphony Orchestra

Two Pianos as a Home Orchestra

by Maureen Buja

With the normalising of a piano at home in the 19th century, music opened up to the masses in a way never anticipated in the 18th century. One of the results of this was music that would have normally been heard only rarely and only in a concert hall, as played by an orchestra, was reduced for performance by groups at home, usually based around a piano.

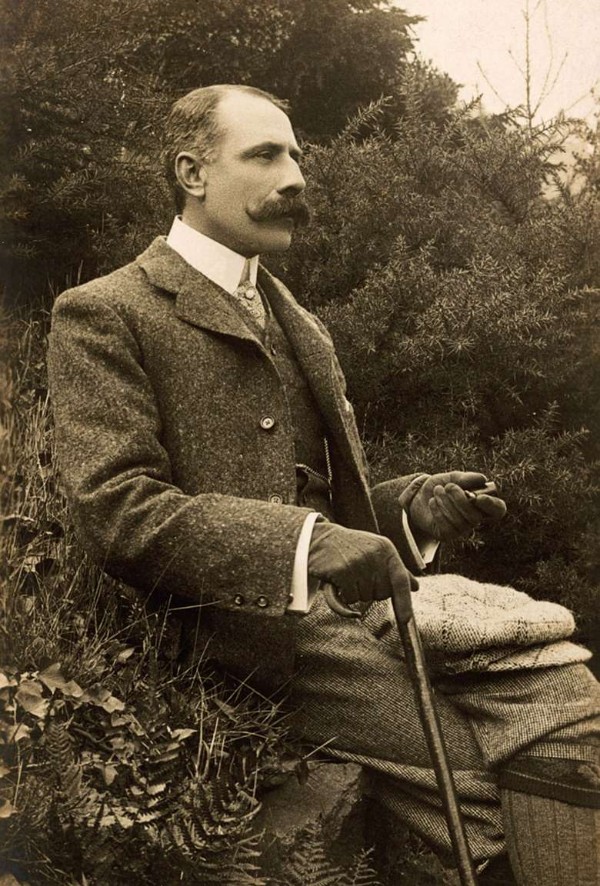

Gustav Holst

By the 1920s, much of this home music-making had been supplanted by the home radio. Recordings also became available, and with a record player, you could have your own orchestra in your drawing room.

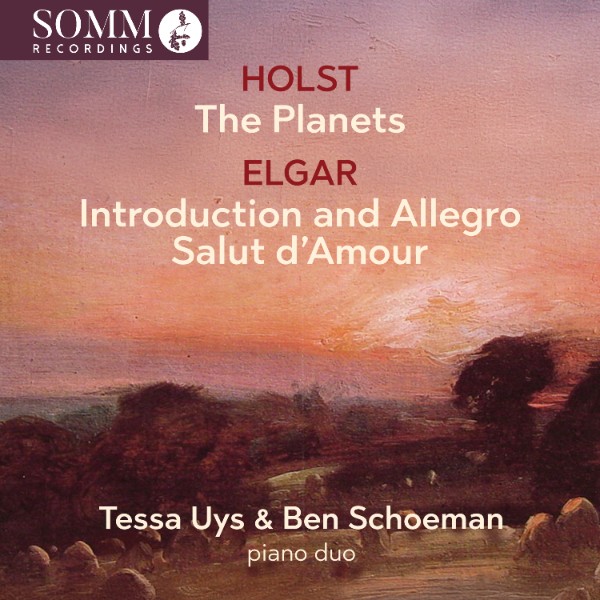

In the early 20th century, however, the piano still held sway, and in this new recording by the piano duo of Tessa Uys and Ben Schoeman, one major work by Gustav Holst and two by Edward Elgar are presented. The transcriptions of Holst’s The Planets, Elgar’s Introduction and Allegro, and the Salut d’Amour give us something back of music in the home.

Gustav Holst’s suite for large orchestra, The Planets, brought Holst’s name into the spotlight. Although admired by his musical friends, few others knew of this Cheltenham-born composer.

The original layout of The Planets was for two pianos, and it was only orchestrated later. Holst suffered from neuritis, an inflammation of the nervous system, and it was easier for him to compose for two pianos than work through a large symphonic score.

With the success of the orchestral version, particularly in a time when astrology and the study of the stars were in fashion, Holst’s two-piano version was set aside and only published some 30 years after the orchestral premiere.

In the two-piano version, the big works, such as Mars, seem too light, but the lighter movements, such as Venus, The Bringer of Peace or Neptune, The Mystic, come across beautifully. One of the particularly good movements in the two-piano version is the flight of Mercury, The Winged Messenger.

Gustav Holst: The Planets – III. Mercury, The Winged Messenger (Ben Schoeman, Tessa Uys pianos)

Edward Elgar

The other English composer who rose from relative obscurity to international fame was Edward Elgar. As in the case of Holst, the piano transcriptions of Elgar’s Introduction and Allegro, and the Salut d’Amour have largely been ignored with the greater fame of their orchestral versions. Whereas Holst made his transcriptions as part of his compositional process, Elgar’s works were done by other hands. Introduction and Allegro was transcribed by Otto Singer II, who made his name with his piano transcriptions of Bruckner’s symphonies. Introduction and Allegro (1905) was written for the string section of the London Symphony Orchestra, with Elgar conducting the premiere.

The second Elgar work, Salut d’Amour, originally entitled Liebesgruß (Love’s Greeting) but retitled in French by Elgar’s German publishers, was a wedding present to his fiancée, Caroline Alice Roberts. Their marriage in 1889 was done with her family’s disapproval, but proved to be a love-match in all the good ways. This melody is probably the most famous of Elgar’s light works, and in his publisher’s catalogue were some 25 different arrangements for all manner of ensembles.

Tessa Uys and Ben Schoeman, piano duo

The two-piano format made important orchestral works accessible for home consumption. In the case of these three works, which are far better known in their orchestral versions, we can hear both the advantages of the genre and some of its limitations.

Holst: The Planets / Elgar: Introduction and Allegro, Salut d’Amour

Tessa Uys and Ben Schoeman, piano duo

SOMM Recordings: SOMMCD 0709

Official Website

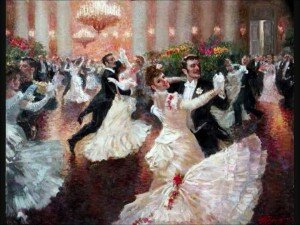

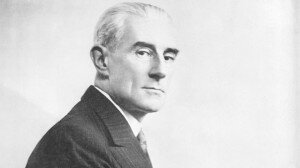

“The Fantastic Whirl of Destiny” Ravel’s La Valse

| “The Fantastic Whirl of Destiny” Ravel’s La Valse |

by Frances Wilson July 4th, 2019

What is Ravel’s La Valse about? Is it a portrait of the disintegration of decadent pre-First War Europe, the dying embers of the Belle Epoque? Or simply a rollicking dance, a sensuous hommage to the Viennese Waltz?

Viennese Waltz

But by 1919 everything had changed, the composer himself profoundly affected by his wartime experiences. Vienna was a city shattered by war, in the grip of famine, and the waltz a bitter, poignant reminder of a vanished era. The impresario Sergei Diagheilev requested Ravel write La Valse, but it wasn’t the work he expected and he refused to stage it, claiming it was “not a ballet” but “a portrait of a ballet”. Ravel published the piece as a “choreographic poem for orchestra”, and the first performance of the orchestral version was in December 1920 in Paris. The work was eventually danced in Antwerp in 1926 by Ida Rubenstein’s troupe (which also premiered Ravel’s Bolero).

Ravel: La Valse

Maurice Ravel

But Ravel denied the work had any symbolic meaning, describing it as “a dancing, whirling, almost hallucinatory ecstasy, an increasingly passionate and exhausting whirlwind of dancers, who are overcome and exhilarated by nothing but ‘the waltz.’”

***

Ravel transcribed the orchestral version for two pianos and piano solo, and the very first performance of the work was actually given in its two-piano form, with Ravel as one of the performers.

Here a pianist friend of mine, who plays in a piano duo, reflects on the experience of learning and performing La Valse:

“Learning the two-piano version of La Valse was a treat. When Neil first suggested that we learn La Valse, I thought it might be beyond us, but we both worked hard at our parts over several months, and to our amazement it gradually came together…

As for performing La Valse, the orchestral version is of course familiar from many recordings and concerts, and in the back of one’s mind is the sound of the different instruments in Ravel’s orchestration. At first I felt very conscious of how the cellos and double basses, the two harps, the brass, or the woodwind, would sound at different points in the score.

But in fact as a pianist, you can enjoy being yourself in this music, without needing to mimic an orchestra all the time: the richness of Ravel’s two-piano sound provides plenty of tonal palette to work with, and much of the pleasure of learning the piece was learning to exploit to the full the contrasts in sound that one can achieve. We enjoyed the challenge of handing melodies from one piano to the other, trying to make the dynamics merge seamlessly between two instruments, learning to be really hushed and mysterious, or hushed and threatening, and conjuring the lilt of the Viennese waltz rhythm.

The final few pages certainly are extraordinary, as the waltz music seems to disintegrate into fragments and accelerates towards a wild climax. As a pair of pianists, you have to hold your nerve, and careful preparation was really essential to be confident that our parts would really fit together and not fall to bits. It was a balance between being accurate and careful, but somehow also letting caution fly to the winds to convey a sense of whirling excitement. In fact, of course, as so often in piano music, the trick was to be really on top of the part, so that you just knew that it would work every time: then you could remain calm and in control, but grasping the music with determination and energy so that the audience felt gripped and excited, not us!”. Julian Davis

“Through whirling clouds, waltzing couples may be faintly distinguished. The clouds gradually scatter: one sees […] an immense hall peopled with a whirling crowd. The scene is gradually illuminated. The light of the chandeliers bursts forth […]. Set in an imperial court, about 1855.” Maurice Ravel

Whatever one’s interpretation of La Valse, there is no doubt Ravel masterfully achieves his vision in the music.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)