It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Tuesday, December 3, 2024

Accent - Let It Snow! (Christmas Jazz feat. Gordon Goodwin's Big Phat Band

Sunday, December 1, 2024

Christmas Medley - Joslin - Live with the Irving Symphony Orchestra

Licad to reconnect with Chopin in Carnegie Hall concert

When Cecile Licad plays Chopin’s 24 Preludes, Op. 28 on Dec. 5 at the Carnegie Hall in New York City, she will once more assert her distinguished link with the legendary Polish composer who died on Oct. 17, 1849 in Paris at the age of 39.

Licad is the first Filipina recipient of the Grand Prix du Disque Frederic Chopin for her interpretation of Chopin No. 2 with the London Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Andre Previn.

The acclaimed pianist was last heard at the Carnegie Hall in 2016 with the Philippine Philharmonic Orchestra where she received a standing ovation.

Saturday, November 30, 2024

Elgar: Pomp and Circumstance | BBC Proms 2014 - BBC

Friday, November 29, 2024

𝗛𝗮𝗽𝗽𝘆 𝗕𝗶𝗿𝘁𝗵𝗱𝗮𝘆, 𝗦𝗶𝗿 𝗥𝗲𝘆! ❤️

Bringing Folk Music to Life: Grieg’s Lyric Pieces

by Maureen Buja, Interlude

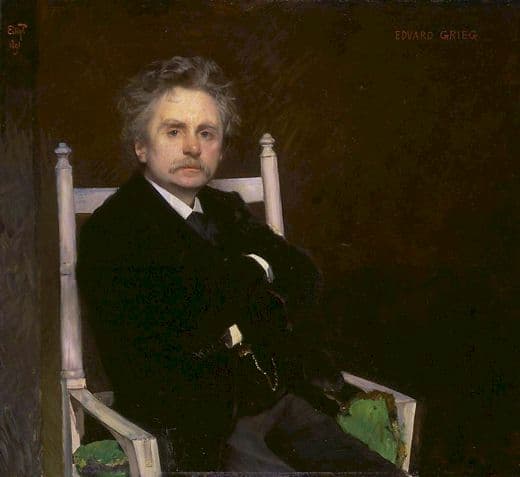

Eilif Peterssen: Edvard Grieg, 1891 (Oslo: Nasjonalmuseet)

Edvard Grieg (1843–1907) was born in Bergen, Norway, and when his skills were recognised by the violinist and composer Ole Bull, he was sent to Leipzig at age 15 to attend the conservatory. Although he later complained about the conservatory, there is no doubt that he received very good and solid musical training. In a city with an extremely active musical life, he heard music he never would have encountered in Norway and it made a lasting impression on him.

When he returned to Scandinavia, he first went to Copenhagen and there started to make his name as a composer. Meeting the Norwegian composer Rikard Nordraak, Grieg came to believe, as Nordraak did, that the future of Norwegian music lay in nationalism and that folksong was key to this.

In 1866, Grieg returned to Norway and settled in Christiana, a part of the capital city of Oslo. Although he wrote many major works, his identity with folk music tainted his reputation as someone who simply borrowed from folk music. Grieg’s own compositional style followed that of traditional Norwegian music: ‘Much instrumental Norwegian folk-music is built from small melodic themes, units which are repeated with small variations in appoggiaturas and sometimes with rhythmic displacements’. Development sections are rare. In following this style, he made it difficult for listeners to tell the difference between his original works and folk music borrowings.

The rise of the piano (it’s estimated that in 1910, more than 600,000 pianos were produced) gave Grieg a ready audience for his piano pieces. They were so popular that his publisher, C.F. Peters in Leipzig, eventually gave him an annual salary for the right to have first choice of his new works.

In his collections of Lyric Pieces, there were eventually 66 works published in 10 albums in the 34 years between 1867 and 1901. His fifth book, Op. 54, published in 1891, is considered to contain his best work in the series. The idea of Nature binds the collection together, and the source material is Grieg’s own, not coming from folk music.

The fourth piece in the collection, the March of the Trolls, takes the equivalent of the Norwegian boogieman as its subject. When the irritable, short-tempered trolls come out after dark with their plans to wreak havoc on quiet households everywhere, beware!

This piece, originally for piano, was orchestrated by conductor Anton Seidl for the New York Philharmonic as part of a work he called Norwegian Suite. This was later revised by Grieg as Lyric Suite with one piece removed, another added, and the order shifted. Grieg’s revised version replaced Seidl’s original version, which is rarely heard anymore.

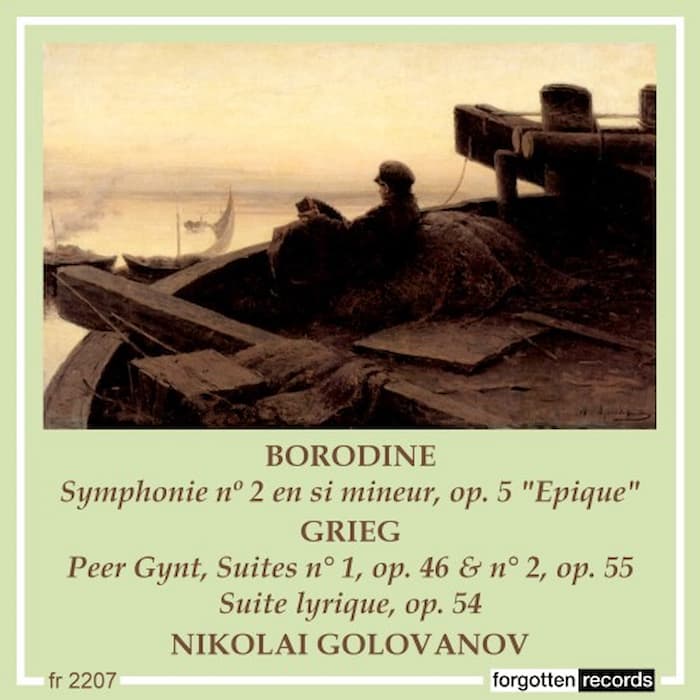

Golovanov (R) and Shostakovich (L)

This recording was made in Moscow in 1949, with Nikolai Golovanov leading the Orchestre Symphonique de la Radio de l’URSS. Soviet composer and conductor Nikolai Semyonovich Golovanov (1891–1953) was one of the leading conductors of his time, and was extensively associated with the Bolshoi Opera. He was recognised as a People’s Artist of the USSR and Honoured Artist of the RSFSR, was awarded the Stalin Prize Winner four times, and was also awarded the Order of Lenin, Order of the Red Banner of Labor, Medal ‘For the Defence of Moscow’ and Medal ‘For Valiant Labor in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945’. He was dismissed by Stalin over a disagreement about casting a Jewish singer for the title role in a recording of Boris Godunov. His friends said it was his shame over this dismissal that led to his death.

Performed by

Nikolai Golovanov

Orchestre Symphonique de la Radio de l’URSS

Recorded in 1949

Why Are We More and More Attracted to Slow Music?

by Doug Thomas, Interlude

Ludovico Einaudi © Decca/Ray Tarantino

Over the past fifty years, there has been a rise of interest for this type of music, and more people seem to be attracted to it — whether they are the creators or the listeners. It seems it has become the backdrop of many people’s off-time, too. Some would say it is by necessity, a counter-reaction to the busyness that our lives are now stuck into, and others would say it is by taste. Whatever the reason is, it is definitely there and growing more and more.

Ryuichi Sakamoto – Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence

Bryars, Richter, Einaudi, Pärt, Sakamoto or Frahm and Arnalds. All these composers, in their own ways and through their works, started or participated in launching a considerable wave of smaller, lesser-known — and often amateur — musicians and composers whose mantra has been to slow down, turn the dynamics down and reduce the musical information. These composers have written the soundtracks of our modern-day workspaces. They are in the background of our offices, in public spaces, in our apps, in our TVs and in our films. And even at times, they are the music which we play while we sleep. They are often unknown or unrecognised. But they represent a lot of the music which is present in our daily lives. If there is a meditative and relaxing element to this music being created, it is not emerging from a new age or spiritual intention, but rather the wish to offer an alternative to the busy lives that we all live and allow art — once again — to provide an escape to reality.

Brian Eno: There Were Bells

Of course, one cannot mention slow music without venturing into the world of ambient music, and particularly the impact of Eno who has been a pioneer in this genre. With his work on ambient music, Eno has allowed composers to accept the slowing down of pace and slow musical development, and through the works of the minimalists, the focus on smaller structures and simpler concepts. His influence can be felt in current composers today; a great example of that is Richter and his Sleep project. The downside to the phenomenon of slow music is that it seems that all of it ends up being the same. Slow and calm music is based on simpler structures and less musical devices being used. Therefore the sense of repetition between works and artists appears quicker, and many composers fail to produce truly original music, and often it appears as paper copies of the original artist. The rhythmic, melodic and harmonic language is often the same, and there is not much space for exploration. In other words, it sometimes seems like a lot of quiet noise, which no one really wants to pay attention to.

Ludovico Einaudi – Nuvole Bianche (Live From The Steve Jobs Theatre / 2019)

The attention span of the human brain seems to have decreased, and therefore, it would seem that busy and complex music is rejected in favour of simpler, more balanced music –– who wants to listen to Wagner today? The function of music must have changed a lot too, and many people perceive it as a sound decoration rather than a proactive act of listening. And therefore a calmer, quieter tapestry of sound works better than a busy and stimulating musical work. It has taken, like Satie foresaw, a decorative element to our life. One must ask though; is it also that we are less educated to music than we were before? The times before the invention of the radio and the television asked for people to learn how to perform their own music for their own enjoyment. Or perhaps the fact that music is so omnipresent in our lives — it is hard to spend a day without hearing some form of music — affects how we want to experience music when it is intentional — and perhaps less busy.

On This Day 29 November: Giacomo Puccini Died

by Georg Predota, Interlude

Giacomo Puccini in Torre del Lago, where he lived for thirty years

Like his colleagues before, the physician discovered nothing suspicious beyond a slight inflammation deep down the throat. He advised Puccini to take a complete rest, abstain from smoking and come back in fourteen days. While his family was clearly relieved, Puccini knew that things weren’t right.

Giacomo Puccini: Turandot, “Tu che di gel sei cinta”

Unbeknownst to his family, Puccini consulted yet another specialist in Florence who diagnosed a “walnut-sized advanced extrinsic cancer of the supraglottis.” Tonio refused to accept the diagnosis but was told in no uncertain terms that his father was suffering from cancer of the throat in so advanced a stage that an operation would be futile. After consulting a number of eminent specialists, it was suggested that treatment by X-ray “was the only method likely to arrest the rapid progress of the disease.”

Puccini in 1924

As this kind of treatment was in its infancy, there were only two clinics in all of Europe where the method had been tried out with some success. Puccini decided to consult Dr. Ledoux in Brussels, and he wrote to his librettist Adami on 22 October 1924, “I am leaving soon… Will they operate on me? Shall I be cured? Or condemned to death? I cannot go on like this any longer. And then there is Turandot… Puccini departed for Brussels on 4 November 1924, taking with him sketches for the love duet and the finale of the last act, thirty-six pages in all.

Giacomo Puccini: Turandot, “Nessun dorma”

The first part of the experimental treatment saw Dr. Ledoux place a collar containing radium around Puccini’s neck. Puccini reports, “I am crucified like Christ! External X-ray treatment at present—then crystal needles into my neck and a hole in order to breathe… What a calamity! God help me. It will be a long treatment, six weeks, and terrible.”

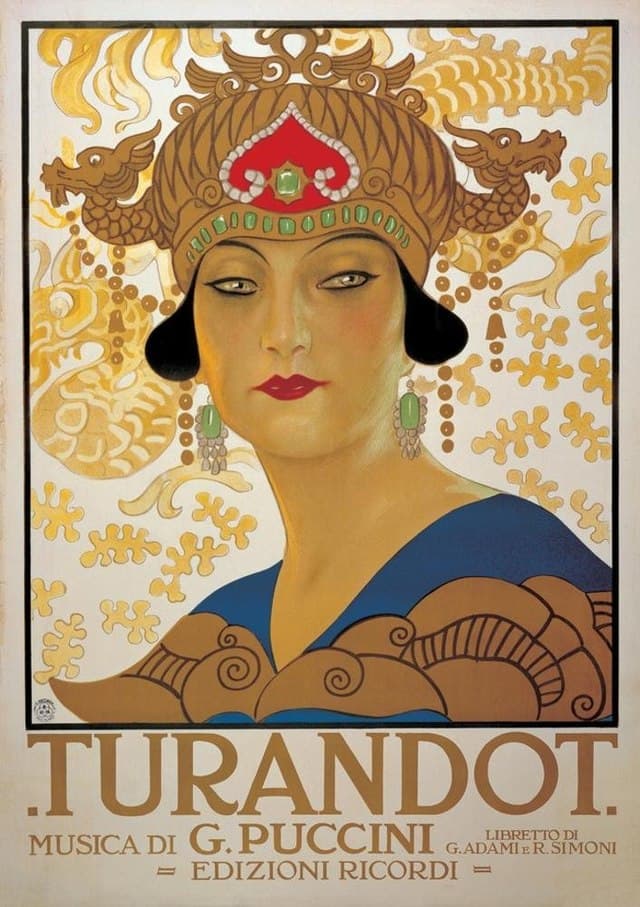

Poster of Turandot‘s performance

During his initial treatment stage, Puccini was not confined to bed but was allowed to leave the clinic. He went to see a performance of Butterfly at the Theatre de la Monnaie, and his clinical condition improved. Puccini visited the local markets and went out for luncheons, and he started smoking again. The second part of the treatment commenced on 24 November, when seven needles were inserted into the tumor in an operation that lasted three hours and forty minutes. Although Puccini suffered agonizing pain, Dr. Ledoux was apparently satisfied that Puccini would pull through.

Memorial plate of Puccini

Unexpectedly, however, Puccini collapsed in the evening of 28 November and he died of heart failure at 4 am on 29 November 1924. A biographer writes, “Dr. Ledoux was so shattered by this sudden turn of events that, driving home in his car afterward, he is said to have fatally injured a woman pedestrian.”

Giacomo Puccini: Turandot, “Del primo pianto si, straniero”

When news of Puccini’s death reached Rome, a performance of La Boheme was stopped, and the orchestra spontaneously played Chopin’s “Funeral March.” The funeral ceremony took place on 1 December in Brussels, and mourners silently lined the street from the clinic to the Church of Ste Marie. When Mme Laure Berge sang Gounod’s “Ave Maria,” a wave of emotion “rippled through the crowd outside the church as the public wanted to share their sorrow for the loss of a famous and very loved Maestro.”

Statue of Giacomo Puccini in Lucca, Italy

Puccini’s body was taken to Milan two days later. Toscanini and the Scala orchestra played the Requiem music from Edgar. Amid torrential rain Puccini’s mortal remains were then conveyed in a solemn procession to the Cimitero Monumentale for provisional burial in Toscanini’s family tomb. On the day of the second anniversary of his death, the coffin was brought to Torre and placed in “the mausoleum, which Tonio had erected in the villa by the lake. Pietro Mascagni spoke the funeral oration, and the conductor Bavagnoli and an orchestra performed music from Puccini’s operas. As for Turandot, Franco Alfano was commissioned to complete the score, a task that took him roughly six months.