It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Monday, September 16, 2024

La Campanella - Paganini/Liszt

Navihanke & Jernej Kolar - Polka, valček, rock'n'roll (v živo)

Mylène Farmer - Ainsi soit je... (Live from Stade de France) - HD

Friday, September 13, 2024

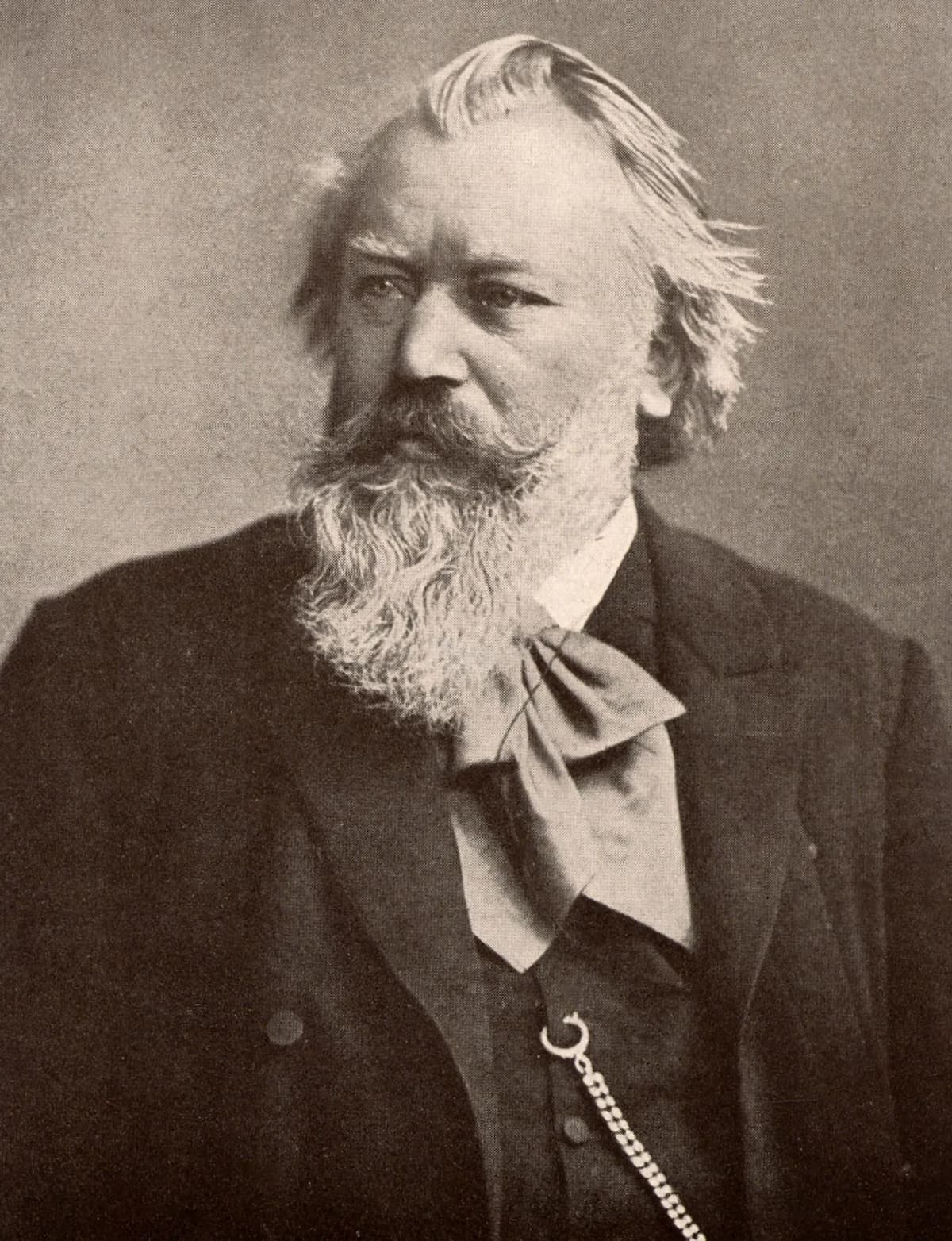

Compositions Dedicated to Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms was seemingly nonchalant when it came to critical assessments of his work or the opinions of his fellow composers. Nevertheless, he proudly and secretly kept a handwritten list of works dedicated to him by other composers. In a small notebook, he compiled a list of 78 musical entries, plays, 4 books and 1 collection of prints. “In his own extensive library, Brahms had copies of most of these works, no doubt sent to him by the authors.” Additional titles were added to his memory shortly after his death. We thought it might be fun to initially explore 10 works dedicated to Brahms.

Robert Schumann: Introduction and Concert Allegro, Op. 134

Johannes Brahms

Let’s start with Robert Schumann’s last work for piano and orchestra, the Concert-Allegro with Introduction, Op. 134. In April 1853, Brahms and the Hungarian violinist Eduard Reményi went on tour, and in Weimar, Joseph Joachim introduced him to Liszt and recommended a visit to Robert and Clara Schumann in Düsseldorf. Around that time, Schumann was working on a work intended as a thirteenth-anniversary present for his wife Clara, but he was so impressed by his young visitor that he dedicated it to Brahms instead.

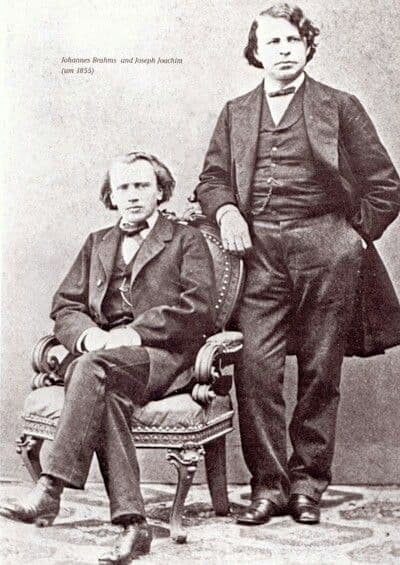

Joseph Joachim: Violin Concerto in D minor, Op. 11 “In the Hungarian Style”

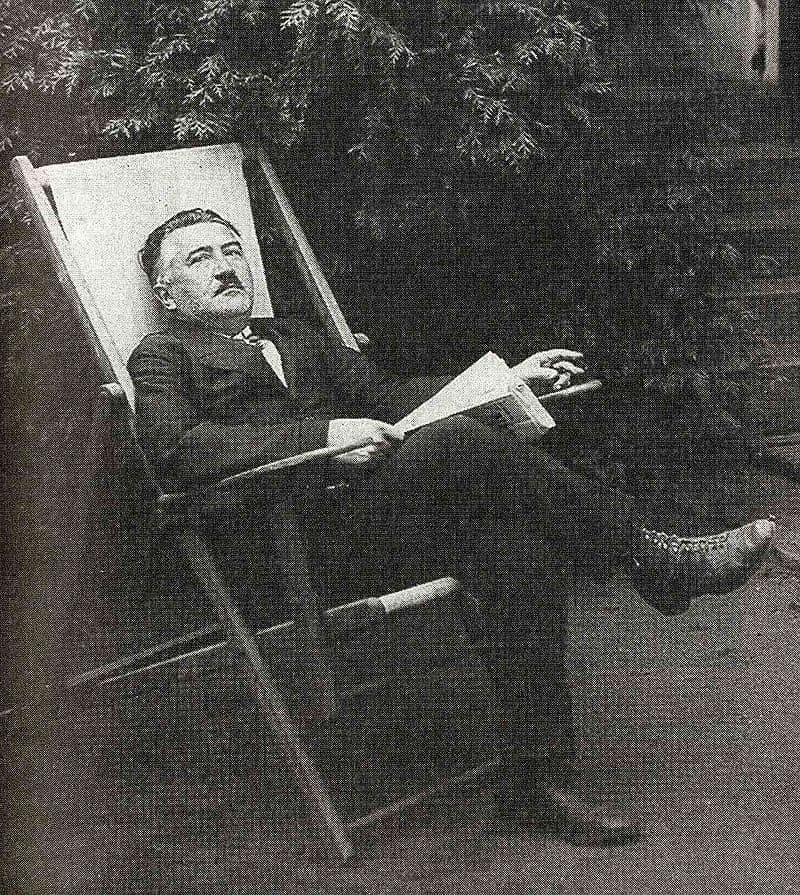

Brahms and Joachim, ca 1855

Talking about Joseph Joachim, we know that the Brahms Violin Concerto was exclusively written for and with the famous violinist. Since Brahms was not a violinist, he sent sketches of the solo part to Joachim for advice. He writes, “I wanted you to correct, and I didn’t want you to have any excuse of any kind; either that the music is too good or that the whole score isn’t worth the trouble. But I shall be satisfied if you just write me a word or two and perhaps write a word here and there in the music, like ‘difficult,’ ‘awkward,’ ‘impossible,’ etc.” Joachim worked painstakingly through the entire manuscript and communicated his suggestions to Brahms, who characteristically ignored most of it. It is probably less well known that Joachim, almost two decades earlier, had dedicated his “Hungarian Concerto” to Brahms.

The Violin Concerto in D minor enjoyed great popularity during Joachim’s lifetime, and like Liszt, Joachim was Hungarian by birth. “Joachim spoke little Hungarian, and he regarded the whole of Magyar culture with a wistful, romantic gaze.” Brahms in turn, had always found inspiration in Hungarian folk music, and he was suitably stimulated by the nostalgic melancholy and passionate abandon native to the “Hungarian Style.”

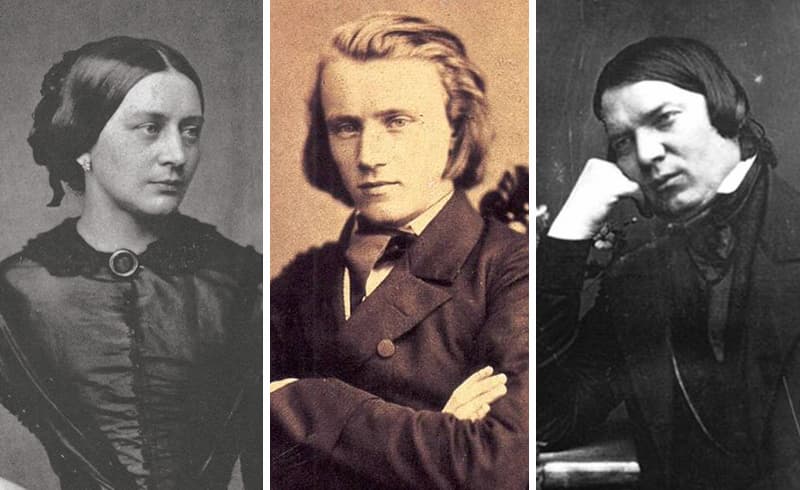

Clara Schumann: 3 Romances, Op. 21

Brahms and the Schumanns

Clara Schumann dedicated the set of Romances, Op. 21 to Johannes Brahms. In late June 1853, Clara wrote three Romances in A minor, F Major, and G minor. However, in the published version, Clara substituted the original A-minor Romance with a Romance in the same key in 1855. The reason for the substitution was a visit of Johannes Brahms to Robert Schumann at the Endenich sanatorium. As she notes in her diary, “on that day the piece I composed is really sad in mood, just as I was when writing it.” This replacement Romance—the original was published separately in 1853—exists in two different versions and autograph sources. The first is dedicated to Johannes Brahms: “Composed for my dear friend Johannes, April 2, 1855,” and the other is dedicated to Robert Schumann: “For my beloved husband, June 8, 1855.” These two dedications are not contradictory, as they clearly reference the two men in her life at that particular time. Her emotional balancing act is reflected in the Three Romances, as she balances Classical formal structures with Romantic harmonies. “The pieces conform to Schumann’s society’s expectations of genre, melody, and form in a piece written by a woman. Its harmonic language meets the expectations of her Romantic peers, yet maintains the sense of restraint found in its form and lack of virtuosic show.”

Theodor Kirchner: Waltzes, Op. 23, No. 2-4

Theodor Kirchner

As we are talking about romances, maybe we should turn to Theodor Kirchner next. He was a capable pianist, organist, and composer, and according to some biographers, “Clara decide to take Kirchner as her lover in 1857 because he was unassertive in character and would appear only when she needed him, and that the affair then continued uninterruptedly for eight years.” That particular narrative seems to have been discredited, but we might suggest with some degree of confidence that their relationship included some sexual intimacy, if only for a short period of time. Kirchner does appear in Clara’s diaries, but “she considered that he had lacked fiber, both as a man and as an artist, and that she was in fact to make several efforts over the next few years to instill some in him.” As she writes, “Pull yourself together, dear Kirchner, you are still a man in full possession of your mental and physical powers.” In 1863, she did call him “my beloved, and expressed feelings of profound love for him.” Within a year, however, the affair had run its course, and Clara told Brahms to never “bring that scoundrel Kirchner to her house again.” Brahms seems not to have been aware of the romantic relationship, and in typical fashion, he did not break his contact with Kirchner. On the contrary, he actively made sure that their relationship was getting closer. Kirchner, in turn, greatly admired Brahms’s music and dedicated his set of waltzes Op. 23 to him.

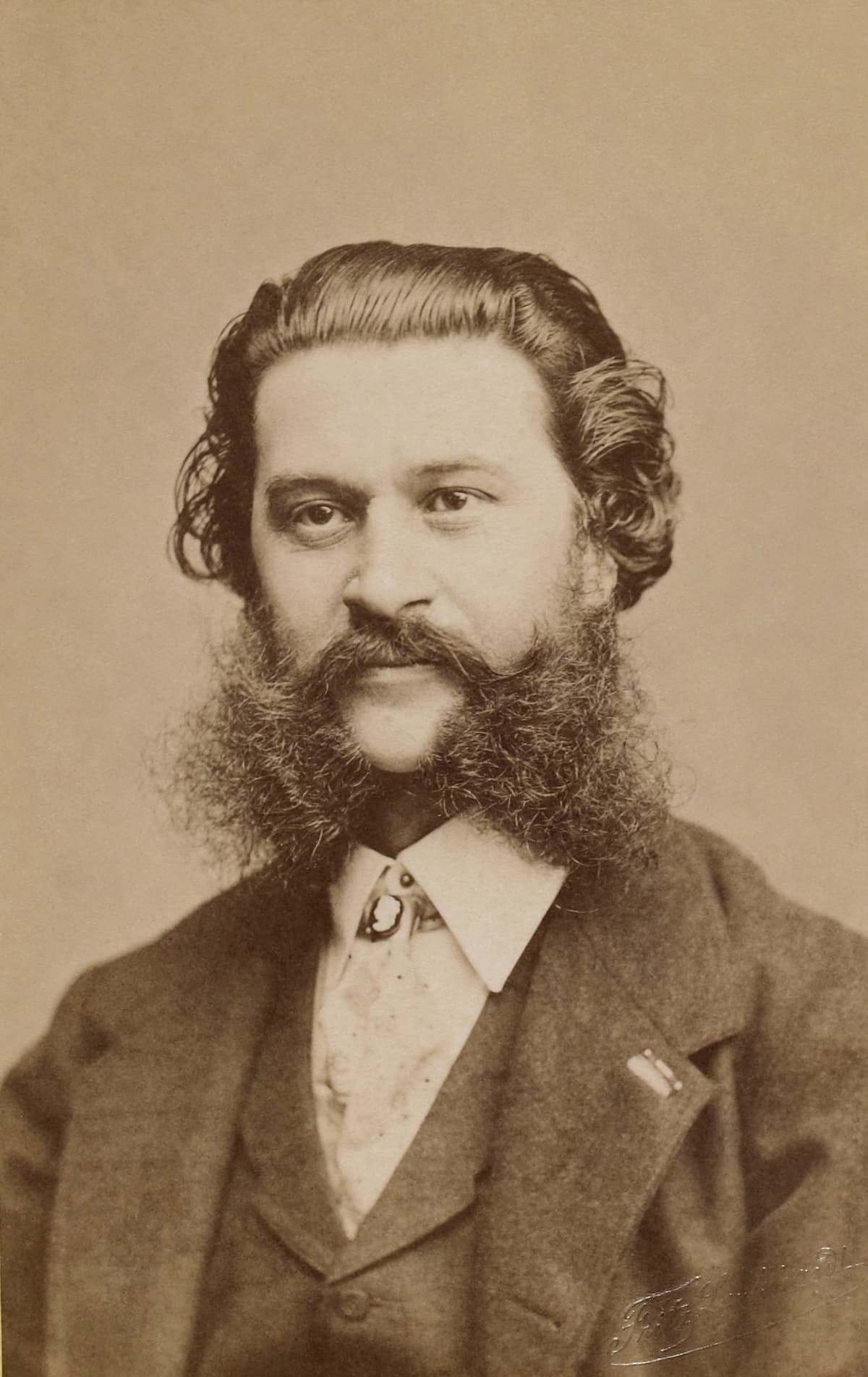

Johann Strauss, Jr. “Seid umschlungen Millionen,” Op. 443

Fritz Luckhardt: Johann Strauss II

When it came to waltzes, Johannes Brahms was a lifelong friend of Johann Strauss II, the “Waltz King” as he was commonly known. A contemporary reports “that Brahms used to play Strauss waltzes at his house with evident delight, sometimes for more than an hour.” He added, “Anyone who has heard Brahms play “An der schönen blauen Donau,” that most beautiful of all the waltzes composed by Strauss, will never forget the intense pleasure of the experience.” We are not sure when Brahms and Strauss met for the first time, but by 1872 Brahms told his friends that Strauss was one of the few colleagues for whom he felt total respect. By the mid 1890s, Strauss and Brahms spent their summers in Ischl, and their respective villas were close by. Brahms, it is reported, would become a regular guest at Sunday dinner, “and usually in a very jovial mood by the end of the meal, would, even without being asked, sit down at the piano and play Strauss waltzes and melodies from his operas.” On one such occasion, Brahms and Strauss are said to have played duets. Brahms marveled at the wealth of Strauss’ melodic invention and stated, “The man overflows with music.” Not to be outdone, Strauss dedicated his waltz “Seid umschlungen, Millionen!” (Be Embraced, Ye Millions!) Op. 443, to Brahms.

Julius Röntgen: Ballade on a Norwegian Folk Song, Op. 36

Julius Röntgen

The composer and pianist Julius Röntgen (1855-1932) did not immediately warm to the music of Brahms. They properly met in Leipzig in 1877 as Brahms was conducting his First Symphony. At a musical soiree at that time, Röntgen played Brahms chamber music in the presence of the composer. Brahms immediately took a great liking to him, but it was during Brahms’s visits to Holland that they got to know each other well. Röntgen played the Second Piano Concerto under Brahms’ direction, and the pianist started to feel increasing admiration for both the man and his music. In fact, Röntgen became a fervent admirer of Brahms’ music. They continued to meet repeatedly, and while Röntgen’s attitude towards Brahms was “solely one of passive reverence,” Brahms expressed his feelings with unusual warmth. As he writes to Clara, “Röntgen is a quite exceptional and most lovable man. He has remained a child, so innocent, pure, frank, and enthusiastic. Not for a long time have I taken such great pleasure in anyone.” Brahms even thought favorably of Röntgen’s compositions, characterising his talents as “light and pleasing.” In return, Röntgen dedicated his 1892 Ballad on a Norwegian Folk Song, Op. 36 to Brahms.

Ferruccio Busoni: Six Études, Op. 16

Ferruccio Busoni

Ferruccio Busoni arrived in Vienna for a two-year stay in 1883. He later remembered that he visited Brahms frequently and, on at least one occasion, showed him compositions that he intended to dedicate to him. We have no information regarding Brahms’ reaction, but since they were rather youthful compositions, it seems that Brahms advised Busoni to study composition and counterpoint with Gustav Nottebohm. Busoni hated his lessons with Nottebohm and quickly discontinued being his student, upon which Brahms supposedly remarked “I have largely ceased contact with Busoni, since I don’t care for children who consider themselves infant prodigies.” Nevertheless, Brahms did subsequently furnish Busoni with a letter of recommendation for study in Leipzig and supposedly remarked “that he would do for Busoni what Schumann did for me.” In the event, Busoni did dedicate his Six Études, Op. 16, to Brahms in 1884, and the stylistic indebtedness is immediately apparent.

Max Reger: 6 Pieces for Piano, Op. 24, No. 6 “Rhapsody to the memory of Johannes Brahms”

Max Reger

Max Reger and Johannes Brahms never met, but in late 1894, Reger referred to Brahms as “the greatest of living composers.” As he writes, “Brahms is nonetheless now so advanced that all truly insightful, good musicians, unless they want to make fools of themselves, must acknowledge him as the greatest of living composers… The Brahms fog will remain. And I much prefer it to the white heat of Wagner and Strauss.” Reger considered Brahms an innovator who used classical forms with amazing freedom of thought, an idea later further developed by Arnold Schoenberg who writes, “Brahms the classicist, the academician, was a great innovator in the realm of musical language, and in fact a great progressive.” Reger had studied at the Conservatory in Wiesbaden under Hugo Riemann, and he began to “adopt Brahms’s technique as a tool for expressing what moved him. Reger absorbed so much of Brahms’ expression and spirit, in part, the ability to get a clear sense of the individuality of his own works.” Reger and Brahms might not have met, but they did exchange a number of letters. In April 1896, Reger sent his Organ Suite to Brahms for approval, and he enclosed a planned Symphony in B minor with a letter asking for permission to dedicate the piece to Brahms. Brahms responded, “I have to thank you most heartily for your letter, whose warm and most friendly words I found exceedingly pleasant. In addition, you are considering rewarding me with the beautiful present of a dedication. My permission for this is really not necessary! I had to smile because you asked me for that while including a work whose all too bold dedication frightens me! Therefore, you may certainly go ahead and add the name of your respectfully humble J. Brahms.” In the end, the symphonic dedication did not materialize, but the “Rhapsody to the memory of Johannes Brahms” appeared around the first anniversary of Brahms’ death.

Josef Suk: Piano Quintet in G minor, Op. 8

Josef Suk

Josef Suk (1874-1935) was Antonín Dvořák’s son-in-law, and he was a member of the “Czech Quartet”, including Karel Hoffmann, Oskar Nedbal, and Otto Berger. They made their highly successful Viennese debut in 1893 and rose to become one of the leading chamber music ensembles in Europe. In fact, they performed until 1933, when Suk retired. Suk remembered that he called on Johannes Brahms during his time in Vienna in 1893 to thank him for the recommendation that had resulted in a state scholarship for composition. Apparently, he was received with Brahms’ “typical mixture of kindness and gruffness.” Brahms asked him, “So you are the scholarship holder Suk? Let me tell you something: Next time, your composition must be more competent, or you won’t get anything.” Brahms also recommended Suk’s Serenade for Strings, Op. 6 to the publisher Fritz Simrock, and in return, Suk dedicated his Piano Quintet Op. 8 to Brahms.

Antonín Dvořák: String Quartet in D minor, Op. 34

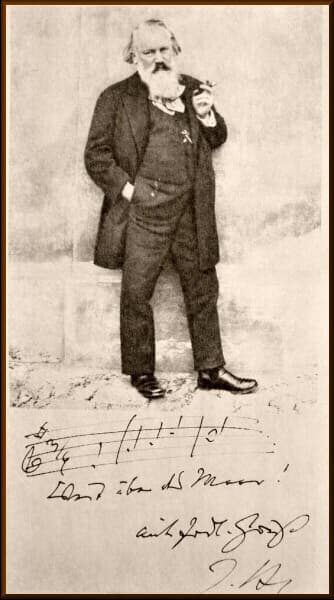

Photograph of Johannes Brahms with greeting to Dvořák

Antonín Dvořák won the Austrian State Prize fellowship prize three times in 4 years. At the head of the selection committee were none other but Johannes Brahms and the fierce Viennese critic Eduard Hanslick. What impressed Brahms about Dvořák was “the seemingly unlimited inventiveness of his melodic materials, his uncanny sense of time and duration, and the dazzling sense of musical line.” A scholar writes, “Brahms’s enthusiasm for Dvořák was rooted in his recognition that he was a composer of such tremendous capacity that he possessed more than the ability to write novel tunes; Dvořák could, in fact, write extended musical essays of the quality to which Brahms himself aspired—modern incarnations of classical models.” Shortly before Dvořák’s third success in 1877, he received a letter from Brahms referring the young composer to his own publisher Fritz Simrock. In a gesture of gratitude, Dvořák pledged to dedicate his Quartet in D minor to Brahms. Brahms, who considered string quartets to be one of the most difficult forms of composition, recommended that Dvořák take a careful look over the score. Dvořák wrote in 1879, “During your last visit to Prague, you very kindly pointed out several places in my compositions, and I must now express my gratitude to you for so doing since I have now seen a great many bad notes, which I have replaced with better ones. I found it necessary to change numerous things in the Quartet in D minor, since you kindly agreed to allow me to dedicate the work to you; it was therefore my solemn duty to dedicate to so famous a maestro a work which fulfills, if not all, at least (please excuse my immodesty) many of the main conditions we may impose upon a work of music.”

Nelson Freire: Robert Schumann - Fantasy in C major, Op. 17 (1983)

A Love Letter in Music: Schumann’s Fantasie in C, Op. 17

by Frances Wilson, Interlude

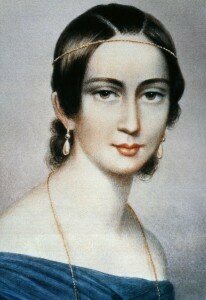

Clara Schumann

Robert Schumann writing to Clara Wieck, March 1838

Never one for disguising his emotions, Robert Schumann wore his heart on his sleeve and his music reflects his joy at being alive – and of being in love. His Fantasie in C, composed in 1836, is a remarkable display of soul-bearing, a piece imbued with passionate and unresolved longing, and the heart-fluttering panoply of emotions from ecstasy to agony which being in love provokes. It was written during a particularly long separation from his beloved Clara Wieck, at a time when their future together was far from certain.

The Fantasie in C is a love letter in music, a culmination of passion, virtuosity and delicacy. No salon sweetmeat, this is a highly demanding, sweepingly romantic large-scale work which pianists approach with trepidation.

Originally intended as a tribute to Beethoven and eventually dedicated to Franz Liszt, the Fantasie is cast in three movements. It alludes to sonata form but like its dedicatee’s B-minor Sonata, Schumann dissolves the formal structure to create a work of striking improvisatory freedom which heightens its emotional impact and poetic narrative. The ‘Clara theme’ which pervades the work is heard immediately in the descending octaves of the right hand. The music is an intriguing mix of grandeur and intimacy: the opening statement, a rolling dominant 9th chord, expresses the full depth of the composer’s passion and the music moves from a state of yearning to one of subdued tenderness before the restatement of the opening. The Adagio coda begins with a secret love message to Clara: a phrase quoted from the last song in Beethoven’s An die ferne Geliebte: “Take, then, these songs, beloved, which I have sung for you.”

Robert Schumann

Sublimely beautiful, tender and intimate, the third movement is an extended song without words, with ravishing diversions into the remote keys of A-flat and D-flat major which create an extraordinary sense of time suspended. In this movement the passion may be downplayed but it is no less powerfully felt. Falling motifs (drawn from the slow movement of Beethoven’s ‘Emperor’ Concerto, and melodies of intense poignancy give way to a section of delicate tenderness, a waltz in all but name with 2 voices – treble and bass – singing together. One can almost picture Robert and Clara clasped in a deep embrace. The coda is an ecstatic declaration, gradually increasing in speed, before pulling back to Adagio for the close and three hushed C-major chords which are at once peaceful and yet tinged with sadness.

Sergei Rachmaninoff The Russian Romanzasei Rachmaninoff: The Russian Romanzas

by Georg Predota, Interlude

The 83 Romances by Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943) include some of his finest and most memorable music. They are part of the Russian contribution to the great 19th-century stream of Romantic songs, and the composer cultivated the musical garden he inherited from Glinka and Tchaikovsky. Like Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff sought, above all, to capture the basic mood of a poetic text in a bright, melodic image, showing it in growth, dynamic intensity, and development.

Sergei Rachmaninoff, 1901

Meanwhile, the complexity of the piano accompaniment is dramatic and equal to the “architectonics of a plot-unfolded opera scene.” Combining the declamatory parts for voice with his supreme pianistic gifts, Rachmaninoff’s romanzas were specifically written for the Russian milieu. Once he left Russia for good at the end of 1917, he composed no more Russian songs.

6 Romances, Op. 4

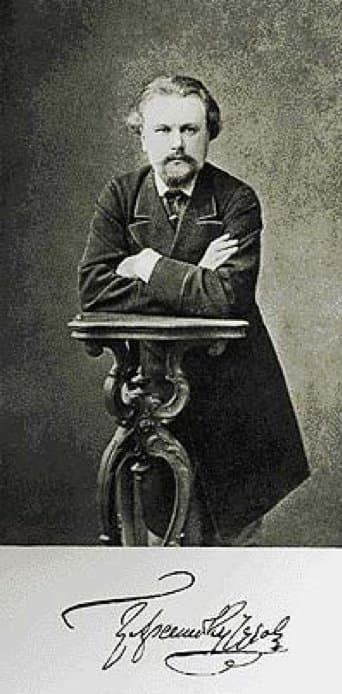

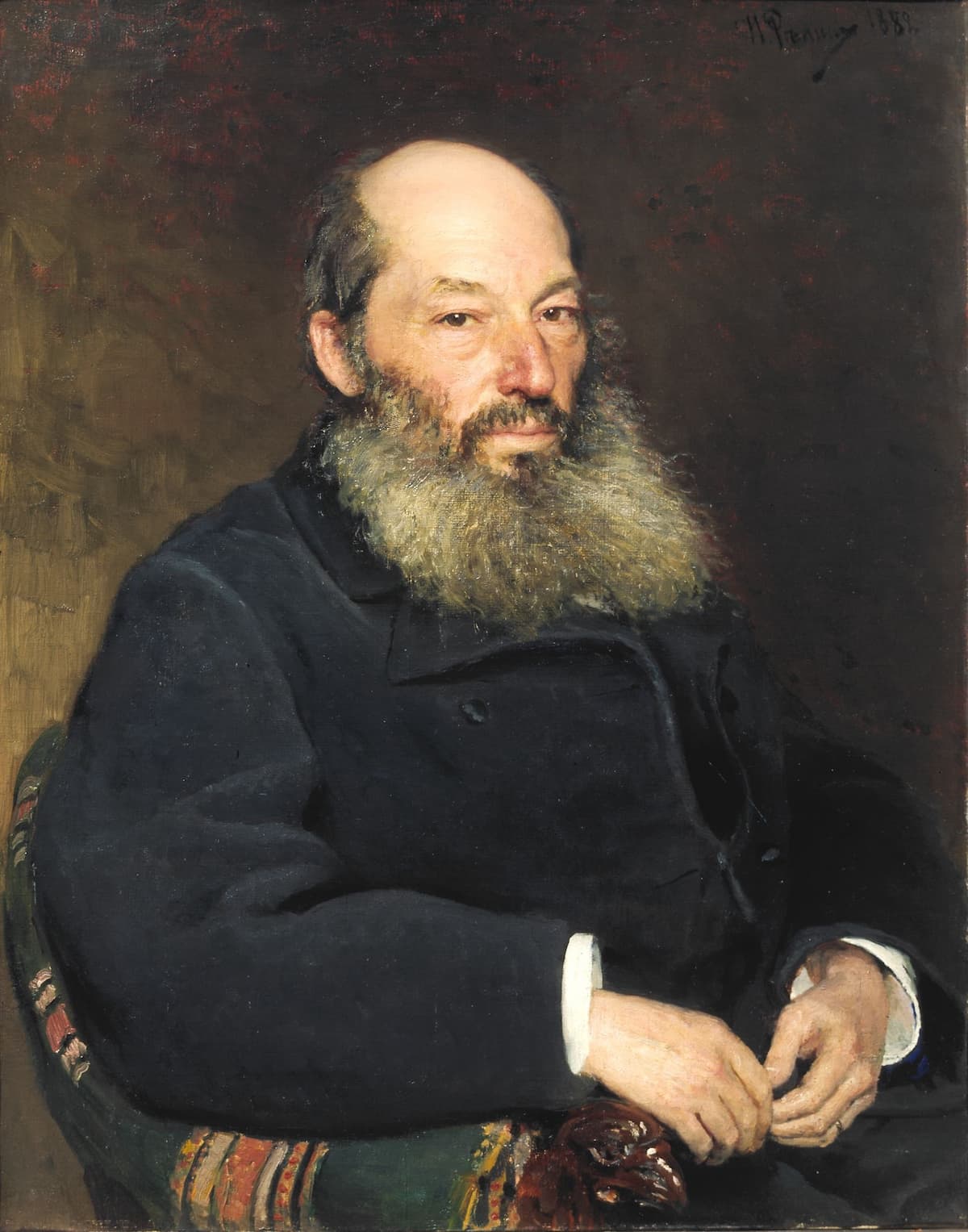

Arseny Golenishchev-Kutuzov

The Six Romances, Op. 4, date from 1890 to 1893, and Rachmaninoff’s student years in Moscow. Demonstrating characteristically idiomatic keyboard writing, the set is informed by a distinctive clarity of texture as the piano accompaniment envelopes piercing vocal melodies of Schubertian incisiveness. “How long, my friend,” based on a poem by Arseny Golenishchev-Kutuzov, features expansive melodic lines and subdued pianistic colours.

Has it been so long, my friend, since I caught

your sad gaze at our farewell moment?

The ray of that farewell

penetrated my soul.

Has it been so long, my friend, since, blundering alone

in a constricting and strange crowd,

I rushed to you, distant beloved,

In a sad dream?

My desires faded… my heart ached…

Time stopped… my mind was numb…

Has it been so long ago, this calm?

But a whirlwind of reunion came rushing…

We are together anew, and the days rush along

As in a flying sea of waves,

And thoughts boil

And songs pour forth from my heart

Brimming over with thoughts of you!

(Trans. Jennifer Gliere)

6 Romances, Op. 8

Afanassi Fet

Rachmaninoff composed music to a substantial number of lyrical texts during his student days. The vast majority of these romances are not included in his first publications, but his choice of poems attests to a wide interest and sure feeling for literary quality. We already find Pushkin, Lermontov, Tyutchev and Afanassi Fet, poets who represent some of the greatest flowering of Russian literature. However, for his second set of songs composed around 1893, Rachmaninoff relied on translations of Ukrainian and German poems.

Four of the Op. 8 set come from Heinrich Heine and Wolfgang von Goethe, and the other two from Taras Shevchenko. The “Water Lily” by Heinrich Heine is a brief two stanza poem of love between the water lilies of the lake and the bright moon above. Rachmaninoff’s setting opens and closes with a delicate but sprightly passage for the piano as the blooming of the lilies greet the moon. The vocal melody is lyrical and highly expressive as the youthful composer presents a warm and affectionate reading of Heine’s poem.

The slender water-lily

Stares at the heavens above,

And sees the moon who gazes

With the luminous eyes of love.

Blushing, she bends and lowers

Her head in a shamed retreat —

And there is the poor, pale lover,

Languishing at her feet!

12 Romances, Op. 14

Fyodor Tyutchev

In the twelve romances of Op. 14, Rachmaninoff strikingly changes the use of the piano. He places significant demands on the pianist, particularly in “Spring Waters”, based on a poem by Fyodor Tyutchev. The words conjure imagery of a violent Russian spring, breaking the ice of winter and threatening to drown the frozen fields. Dedicated to his old piano teacher Anna Ornatskaya, the piano accompaniment rushes forth with unhindered intensity and virtuosity.

White snow still covers all the fields

Yet streams already speak of spring:

Flowing, and waking the sleeping hills

Flowing, and sparkling, chattering all the while.

Proclaiming as they travel, near and far:

‘Spring is coming! Spring is coming soon!

We are the messengers of early Spring

She sent us on ahead, to let you know!

Spring is coming! Spring is coming soon!

Then come the warm and tranquil days of May,

When rosy-cheeked round dances of the young

Will follow in Spring’s train – a merry crowd!’

12 Romances, Op. 21

Sergei Rachmaninoff at 10 years old

During an interview in 1941, Rachmaninoff detailed how extra-musical impressions helped him in the process of creating music. “Ultimately, music is an expression of the composer’s individuality in its entirety,” he explained. “The composer’s music must express the spirit of the country in which he was born, his love, his faith and thoughts that have arisen under the impression of books and paintings that he loves. It should be a synthesis of the composer’s entire life experience.”

In his Op. 21 Romanzas, dating from 1900 to 1902, Rachmaninoff provides a finely controlled balance between voice and accompaniment. And it is once again the piano that offers deep insight into the text. Op. 21, No. 7, “How peaceful,” sets a poem by Countess Glafira Adolfoyna Einerling. The poetess describes a sunset and contemplates the bond between man, nature, and God. Full of gentle lyricism, the music is seemingly simple, but it is easy to hear that the true essence of Rachmaninoff’s musical imagination is already found in these early romances.

How peaceful…

Look there, in the distance

Shines the river like a flame,

The fields lie like a flowered carpet

Light clouds above us…

Here there are no people…

Here there is silence…

Here is only God—and I,

Flowers—and an aging pine,

And you, my dream.

15 Romances, Op. 26

Galina Galina

It took Rachmaninoff almost four years before he returned to setting poetry. The fifteen romanzas of Op. 26 date from the summer of 1906, and they continue to explore some of the declamatory vein introduced in his Op. 21. However, one striking exception is “Before my window,” a poem by Galina Galina nee Glafira Mamoshina. She began writing poetry at the age of 9, and her first poems were published in 1895. She also published a significant number of children’s works, both poem and prosaic, notably two collections of fairy tales. The poetry of her first years is dominated by love lyrics and subjects of spiritual experiences. With consummate skill and imagination, Rachmaninoff weaves a beautiful lyrical line between the voice and the piano.

The cherry tree flowers by my window,

Pensively it flowers in its silver raiment…

And its fresh and fragrant bough

Inclines to me and beckons me…

Blissfully, I inhale in the joyful breath

Of its quivering, airy blossoms,

Their sweet aroma clouds my mind,

And they sing wordless songs of love…

(Trans. Philip Ross Bullock)

14 Romances, Op. 34

Alexander Pushkin

The majority of poems in Rachmaninoff’s Op. 34 was suggested to the composer by Marietta Shaginyan. Of Armenian descent, she grew up in Moscow under privileged circumstances and became one of the most prolific women writers in Russian literary history. She had a lifelong fascination with music and a very close friendship with Rachmaninoff.

As he writes, “Dear Dee, what if I ask you to find me some lyrics for the love songs I’m writing now? Something tells me you must know a whole lot, if not everything, about this. And I would rather have something sad because I’m really not good at writing cheerful things.” The first song of Op. 34 is a text from Pushkin titled “The Muse.” The set also includes the famous “Vocalise,” a song without words, written for a singer of very different gifts, Antonina Nezhdanova, whose lucid tones and light, elegant coloratura had been delighting Moscow Bolshoy audiences.

6 Romances, Op. 38

Antonina Nezhdanova

Rachmaninoff was satisfied and extremely happy with his Op. 34, for “they came to me easily with little trouble. Please, God, that I may continue to work in this way.” However, Rachmaninoff was to write only one more group of songs before he went into exile. Op. 38, written during the Great War in 1916, moves away from the Romantics and turns to Symbolist poetry by Balmont, Alexander Blok, Andrey Bely, Valery Bryusov, and Fyodor Sologub, among them.

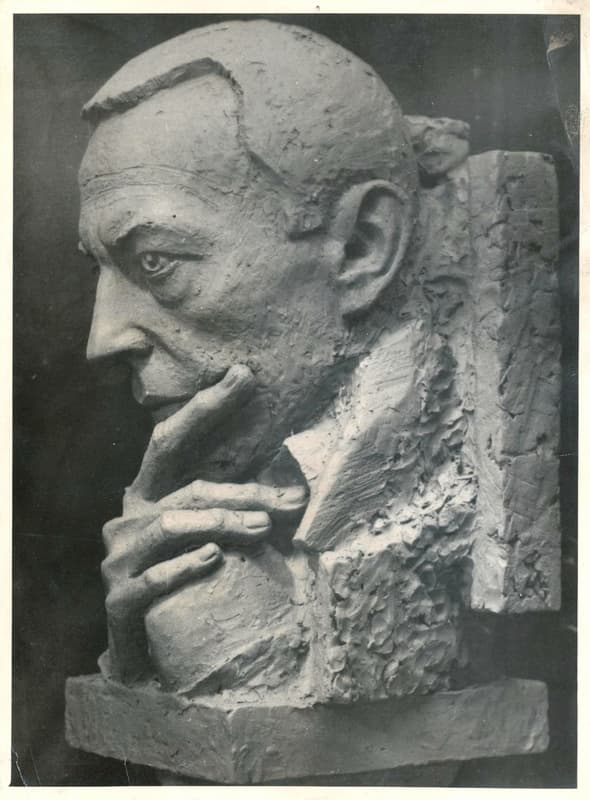

Bust of Sergei Rachmaninoff

Rachmaninoff’s interest in words now took the form not of declamation and its melodic effect but their actual sounds and the implications this had for music. That poetic resonance emerges in almost impressionist textures, and the composer writes, “if everyone wrote nature poems like that, a composer would only have to touch the text, and a song would be made.” “Daisies,” a setting of a poem by Igor Severyanin became Rachmaninoff’s favourite song. Delicately balancing the piano and voice, Rachmaninoff later made a version for piano solo, but he wrote no more Russian romanzas in exile.

Oh, see how many daisies,

Here and there,

They blossom; they are plentiful; they are abundant.

They blossom.

Their petals are three-edged, like wings,

Like white silk;

You are the summer’s might! You are abundant joy,

You are radiant multitude!

Earth prepares to flower with the dew’s draught,

Giving sap to the stalks.

Oh maidens, Oh daisy stars, I love you!

(trans. Elizabeth Wiles)