by

Here, John Gregory, writing in 1766 in his A Comparative View of the State and Faculties of Man with Those of the Animal World, had this to say about what composer?

‘[The style of COMPOSER] sometimes pleases by its spirit and a wild luxuriancy … but possesses too little of the elegance and pathetic expression of music to remain long in the public taste.’

Hmmm. So we want a mid-18th century composer who had spirit and a sense of luxury but lacked elegance…. Mozart? Hummel? No, they’re too late. Gregory was referring to the style of the music of Haydn, who, of all composers of his era, has remained in the public taste where so many of his contemporaries have vanished.

Hardy: Joseph Haydn, 1791

We have two composers with two very different views of conductors. The first, a composer, suffered poor performances in the hands of bad conductors:

‘Conducting is a black art.’

The other, a conductor himself, downplayed the difficulties in a letter to his 10-year-old sister:

‘It’s easy. All you have to do is wiggle a stick.’

It was Tchaikovsky who held the first opinion, given in 1909, and Sir Thomas Beecham in the second quote.

Reutlinger: P.I. Tchaikovsky, c. 1888

Sir Thomas Beecham, 1948

Richard Strauss, on the other hand, felt that certain sections of the orchestra needed to be quelled at all times:

‘Never let the horns and woodwinds out of your sight. If you can hear them at all, they are too loud.’

Igor Stravinsky , himself a composer and a conductor, saw danger in the field of conducting:

‘”Great” conductors, like “great” actors, soon become unable to play anything but themselves.’

and

‘Conducting is semaphoring, after all.’

Richard Strauss conducting

Stravinsky conducting

He also viewed conductors as the ‘lapdogs’ of musical life…which poses an interesting question of which side of Stravinsky was making that statement!

Very few composers or performers had anything good to say about critics.

Richard Wagner thought that ‘the immoral profession of musical criticism must be abolished,’ whereas Beecham saw the problem as one of lack of musical feeling, saying ‘…so often they have the score in their hands and not in their heads.’

Aaron Copland thought that ‘if a literary many puts together two words about music, one of them will be wrong’.

And the critics strike back:

George Bernard Shaw, when accused of being too critical: ‘No doubt I was unjust; who am I that I should be just?’

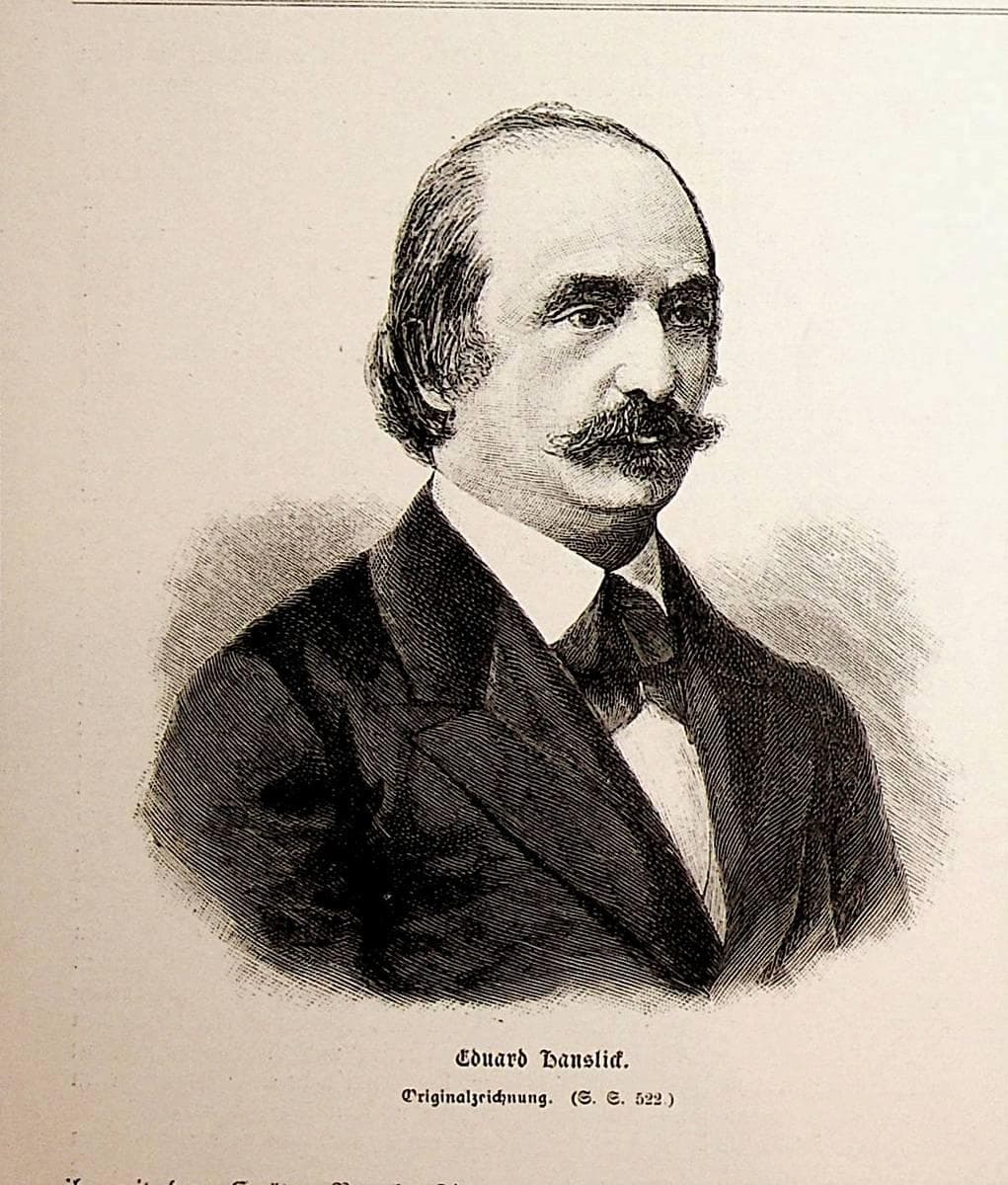

Eduard Hanslick, who wielded great power as critic, took an uncritical view of himself: ‘When I wish to annihilate, then I do annihilate.’

Eduard Hanslick

Oscar Wilde found Chopin to be too emotional: ‘After playing Chopin, I feel as if I had been weeping over sins that I had never committed, and mourning over tragedies that were not my own.’

Sometimes composers are most caustic about their contemporaries. Wagner wondered this about the legacy of Rossini: ‘After Rossini dies, who will there be to promote his music?’

Stravinsky pondered about South American music: ‘Why is it that whenever I hear a piece of music I don’t like, it’s always by Villa-Lobos?’

Some composers write about what they are proudest of. Modest Mussorgsky, known for his songs as much as his symphonic music and opera, said in a letter in 1868 ‘my music must be an artistic reproduction of human speech in all its finest shades’.

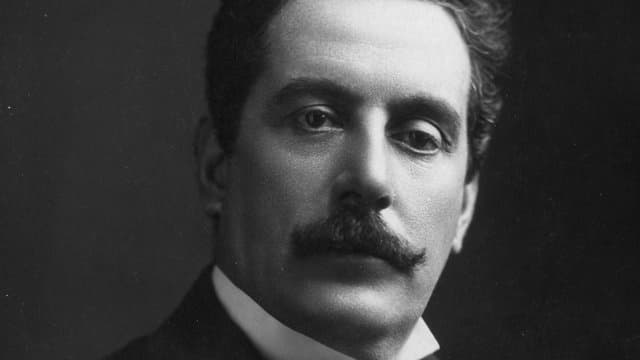

Puccini, understating his talents simply said ‘God touched me with His little finger and said “Write for the theatre, only for the theatre.”’

Giacomo Puccini

Rossini, never one to understate his skill, remarked ‘Give me a laundry-list and I’ll set it to music.’

Stravinsky, who was often so far ahead of his contemporaries musically as to be in another world, said ‘Silence will save me from being wrong (and foolish), but it will also deprive me of the possibility of being right.’

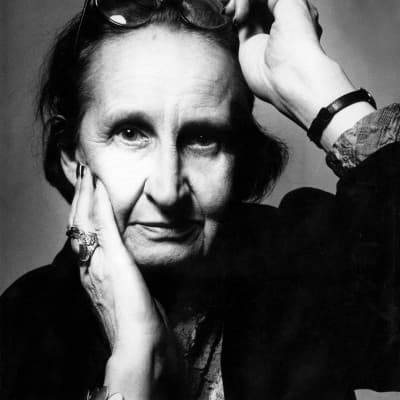

Elisabeth Luytens, who parlayed her contemporary sound into really effective music for British horror films, called her own style ‘eerie weirdness’.

Elizabeth Lutyens

Opinions, opinions … everyone has opinions. Some of them can make us ponder (‘Wagner has lovely moments but awful quarters of an hour’ – Rossini), others make us laugh (‘Hell is full of musical amateurs’ – George Bernard Shaw), and others make us angry (‘There are two kinds of music: German music and bad music.’ – H.L. Mencken) – what’s your opinion?