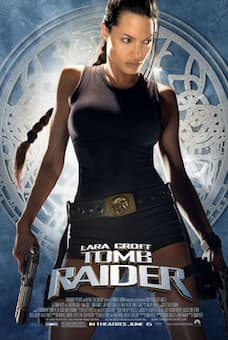

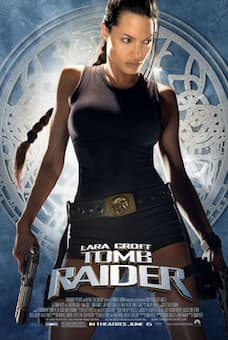

Tomb Raider

I was still too young to actually see the first “Tomb Raider” film release in 2001. But when I first watched it some years later, I thought it was the biggest thing since the invention of the handbag. Finally, there was an empowered women beating up all those macho male characters. Later I played all the video games, and “Lara Croft” became a cultural phenomenon that is still going strong 25 years later. Basically, they are pretty silly movies but you can’t beat swashbuckling action films if you want to enjoy a couple hours of mindless fun. The Hollywood studios have given us countless action/adventure movies, and that formula has been a huge commercial success. No wonder that they called the 1930’s Hollywood’s Golden Age. In Europe meanwhile, audiences had little taste for blowing up the world movies after World War I, so filmmakers tended to focus more on the artistic qualities of film. While American composers of film music “seemingly held that new medium in distain,” they imported the Viennese composers Max Steiner and Wolfgang Eric Korngold. In Europe meanwhile, a significant number of art music composers embraced this new challenge. In France, in particular, a number of big-name composers eagerly adopted the new art form, including Erik Satie, Jacques Ibert, Germaine Tailleferre, Darius Milhaud, and Arthur Honegger.

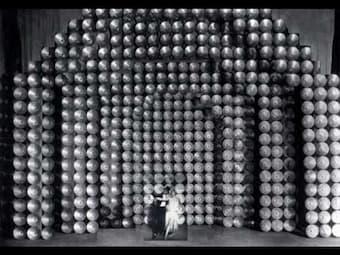

Erik Satie & Francis Picabia, Jean Biorlin (prologue de Relache)

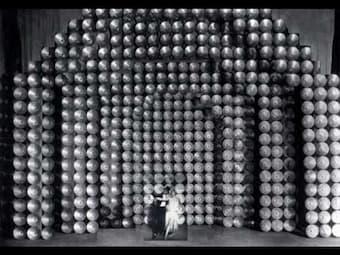

When eccentricity and classical music are used in the same sentence, Erik Satie (1866-1925) immediately comes to mind. Irreverent, disrespectful, contemptuous of tradition, forcefully direct and brutally honest, Satie famously wrote underneath his self-portrait, “I have come into the world very young, into an era very old.” In 1924, Satie collaborated on a ballet production with Francis Picabia, and since both artists had a taste for controversy, audiences immediately knew what to except. It was called Relâche, loosely translated into “No Performance today,” or “Theatre Closed,” and it had really no plot. A female character dances with a changing number of male characters, including a paraplegic in a wheelchair. And there is a man dressed as a fireman who wanders around the stage, pouring water from one bucket into another.

Relâche Part 1

Between acts and after the overture, the film “Entr’acte” was shown. An experimental film by critic Rene Clair, it featured scenes filmed in Paris that included a dancing ballerina with moustache and beard, a hunter shooting a large egg, and a mock funeral procession with a camel-drawn hearse. Satie composed the music for both the ballet and the film, and his score for “Entr’acte” was called revolutionary. “It is an excellent example of early film music, as different segments reflect and support the rhythm of the action and serve as a kind of neutral rhythmic counterpoint to the visual action.” Satie used a number of popular tunes, and while the ballet is little more than nonsensical fragmented spectacle to make Dada proud, “the music is essentially unified and symmetrical.” The premiere, as you might expect, did not go well and audiences and critic attacked “the stupidity of the staging and the inanity of the musical score.” Today we recognize it “as an inventive score without peer, at once durable and distinguished, with “Satie having understood correctly the limitations and possibilities of a photographic narrative as subject matter for music.”

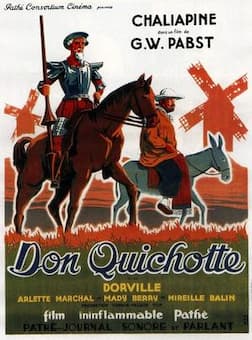

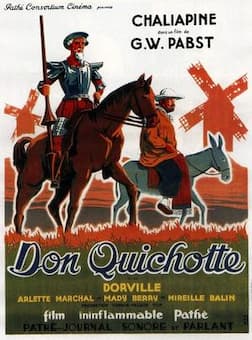

Jacques Ibert: 4 Chansons de Don Quichotte

Don Quichotte

I have always loved the music of Jacques Ibert (1890-1962) because he doesn’t take himself or classical music all too seriously. He once said that he only agreed to write music that he was happy to listen to himself. “I want to be free,” he writes, “independent of the prejudices which arbitrarily divide the defenders of a certain tradition, and the partisans of a certain avant garde.” His biographer writes, “Ibert’s music can be festive and gay…lyrical and inspired, or descriptive and evocative…often tinged with gentle humour.” That’s a perfect recipe for writing incidental music for the theater and music for film. In fact, Ibert was a prolific composer when he came to cinema scores, writing music for more than a dozen French films, and two pictures for American directors Orson Welles and Gene Kelly. In 1933, Georg Wilhelm Pabst, one of the most influential German-language filmmakers during the Weimar Republic, directed Don Quixote, the film adaptation of the classic Miguel de Cervantes novel. It was made in three versions—French, English, and German—and featured the famous operatic bass Feodor Chaliapin. The producers separately commissioned five composers—Ibert, Ravel, Delannoy, de Falla, and Milhaud to write the songs for Chaliapin, each composer believing only he had been approached. Jacques Ibert’s music was selected for the film, and Ravel considered a lawsuit against the producers.

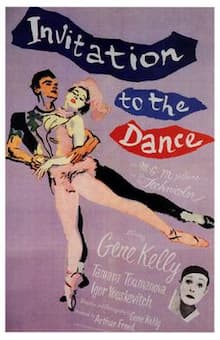

Invitation to the Dance

The American actor, dancer, and singer Eugene Kelly became incredibly famous for his performances in “An American in Paris,” and for “Singin’ in the Rain.” Kelly also starred in “Invitation to the Dance,” the first film he directed on his own. The film is a dance anthology that has no spoken dialogue, with the characters performing their roles entirely through dance and mime. The film consists of three distinct stories, written by Kelly, with the first segment “Circus” set to original music by Jacques Ibert. The plot is a tragic love triangle set in a mythical land sometime in the past. Kelly plays a clown, who is in love with another circus performer, played by Claire Sombert. She, however, is in love with an Aerialist, played by Youskevitch. The Clown, after entertaining the crowds with the other clowns, sees his love and the Aerialist kiss and wanders into a crowd in shock. That night he watches them dance together, and after the Lady finds him with her shawl, he confesses his love to her. The Aerialist finds them and thinks she has been unfaithful and leaves her. Determined to win her, the Clown tries to walk the Aerialist’s tightrope himself, only to fall to his death. Dying, he urges the two lovers to forgive each other. By the way, the movie was a colossal failure at the box office, but it is today regarded “as a landmark all-dance film.”

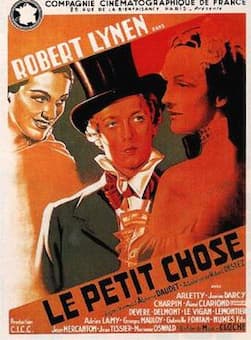

Le petit chose

Germaine Tailleferre (1892-1983) was the only female member of the French group of composers known as “Les Six.” She was well-known for her intimate chamber music compositions, but it is generally less well-known that she scored music for thirty-eight films! And that includes music for a series of documentaries, and a number of wonderful collaborations with film director and producer Maurice Cloche. His career spanned for over a half-century, and he produced spy thrillers and films with religious and social themes. He is probably best known for “La Cage aux Oiseaux” (‘The Bird Cage); “Le Docteur Laennec,” the story of the inventor of the stethoscope; “Ne de Pere Inconnu” (Father Unknown) and “La Cage aux Filles” (The Girl Cage). Cloche founded a film society for young talents in 1940, which later became the Institute of Advanced Film Studies and France’s leading film school. Cloche was part of a group of directors that focused on poetic realism, but he did not neglect social subjects. His most famous documentaries on art included “Terre d’amour,” “Symphonie graphique,” “Alsace,” and “Franche-Comte.” In 1938 Cloche turned the autobiographical memoir by Alphonse Daudet into the film Le Petit Chose (Little Good-for-Nothing) starring Arletty, Marianne Oswald, and Marcelle Barry. The title is taken from the author’s nickname, and “Little Good-for-Nothing” is forced to accept a job as a Latin teacher in a college. He is expelled for having naively trusted one of his colleagues, and he departs to join his brother in Paris where he is dreaming of great literary career. As an interesting side-note, the movie features 14-year-old classical guitarist Ida Presti in a supporting role as a guitar player. Tailleferre composed a wonderfully flowing film store that is at once “bold and original, dissonant and exploratory, vigorous and soothing.” In her day, Tailleferre was greatly admired for her film work, which was “likened to the wispy work of the popular watercolorist Marie Laurencin.”

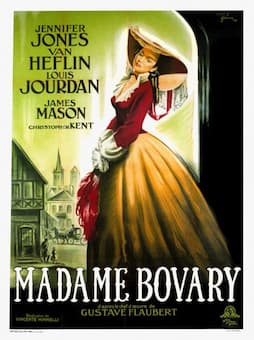

Darius Milhaud: L’album de Madame Bovary

Madame Bovary

Darius Milhaud (1892-1974) composed over 400 compositions during his life, and given his love of the cinema, he also wrote music for 25 films. It all started with his first major success, the 1919 Surrealist ballet “Le Boeuf sur le toit,” (The Ox on the Roof). That work was originally subtitled a “Cinéma-symphonie,” and it featured fifteen minutes of music “rapid and gay, as a background to any Charlie Chaplin silent movie.” Milhaud was already composing music in the silent era, “with the now lost score to accompany Marcel L’Herbier’s avant-garde melodrama “L’Inhumaine.” The music is said to have matched the “film’s abrupt, expressionist rhythm, climaxing—for a scene where the hero resurrects his dead love in a futuristic laboratory—in a bravura cadenza scored solely for percussion instruments.” Always eager to experiment, Milhaud brought the opera into the cinema, as he used a backdrop movie screen to disclose the thoughts of his characters in his opera Christophe Colombe. In Dreams That Money Can Buy of 1947, Milhaud collaborated with the Surrealist/Dada super stars Max Ernst, Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, Alexander Calder, and Fernand Léger, and he received a visit from Renoir while he was composing the score for Madame Bovary.

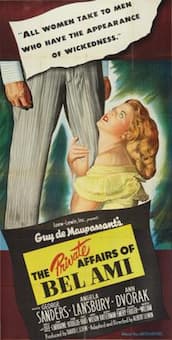

The Private Affairs of Bel Ami

Milhaud’s love for experimentation needed an eclectic use of music. He did admire Debussy and Mussorgsky but truly hated Wagner. Milhaud “happily threw in elements of whatever took his fancy—jazz, Brazilian dance rhythms, the medieval troubadour songs of his native Provence. Rather than cast his music in a predetermined style, he preferred to adopt whatever forms and materials seemed appropriate to the given task. This adaptability, together with his fluency of inspiration should have made him an ideal film composer. But his relationship with the movie industry remained oddly uneasy.” Milhaud spent much of his later life in America, but hated working for Hollywood. “He disliking the system of handing over the composer’s short score to professional orchestrators who churn out on a commercial scale musical pathos à la Wagner or Tchaikovsky.” He did, however, accept one Hollywood assignment titled The Private Affairs of Bel-Ami directed by Albert Lewin. Milhaud called him a “highly cultured man, and what is even rarer in those circles, genuinely modest.” Milhaud did orchestrate his own music, conducted the recording session and was present during the mixing. “The result was a score that vividly evoked the Paris of the Belle Epoque, but without the usual wash of romantic nostalgia.”

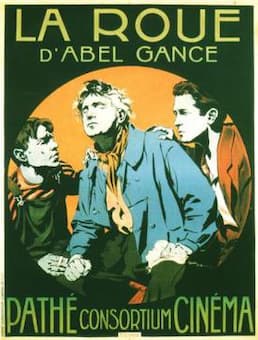

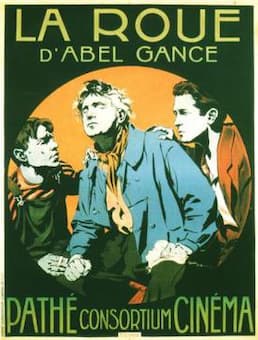

La Roue

Arthur Honegger (1892-1955) was critically acclaimed for both his concert music and his film scores during the interwar years in France. In terms of film scoring, Honegger is best remembered for his collaboration with Abel Gance, a pioneer film director, producer, writer and actor. Gance pioneered the theory and practice of montage, and he is best known for three major silent films J’accuse (1919), La Roue (1923), and Napoléon (1927). And Honegger wrote the music for all three silent films. J’accuse juxtaposes a romantic drama with the background of the horrors of World War I, and it is sometimes described as a pacifist or anti-war film. Work on the film began in 1918, and some scenes were filmed on real battlefields; can you imagine? The film’s powerful depiction of wartime suffering, and particularly its climactic sequence of the “return of the dead” made it an international success, and confirmed Gance as one of the most important directors in Europe. The only surviving score for the 1922 melodrama La Roue is an overture scored for medium-sized orchestra. There has been much speculation as to the rest of the music, and it is said “that Honegger put together a score consisting of pieces of his own and music from the classical repertoire.”

Arthur Honegger: Napoleon Suite

Albert Dieudonne as Napoleon_1927

Abel Gance’s silent masterpiece Napoleon of 1927 “exceeds the parameters of virtually every aspect of film culture. In the 1920s, its temporal gigantism horrified producers and its aesthetic invention flustered critics.” The film is recognised as a “masterwork of fluid camera motion, produced in a time when most camera shots were static. Many innovative techniques were used to make the film, including fast cutting, extensive close-ups, a wide variety of hand-held camera shots, location shooting, point of view shots, multiple-camera setups, multiple exposure, superimposition, underwater camera, kaleidoscopic images, film tinting, split screen and mosaic shots, multi-screen projection, and other visual effects.” It tells the story of Napoleon’s early years, and Gance had planned it to be the first of six films about Napoleon’s career, basically a chronology of great triumph and defeat ending in Napoleon’s death in exile on the island of Saint Helena.

Abel Gance and Arthur Honegger, 1926

Gance had struggled to make the first film, and given the enormous costs involved, he understood that the full project was impossible. Honegger believed that “cinematic montage differs from musical composition in that, while the latter depends on continuity and logical development, the film relies on contrasts. Music and sound must, therefore, adapt themselves to strengthening and complementing the visual element, while the whole must be an artistic unity.” Until now, the original cue sheet for Honegger’s music to Napoleon has not been found, so we don’t know exactly what music was played when. However, a number of musical autographs and orchestrated manuscripts have survived, and have been compiled into a wonderful Napoleon Suite sequence. There are so many more beautiful French movies and corresponding gorgeous music to explore, but in the next blog we will turn our attention to the two Russian giants Dmitri Shostakovich and Sergei Prokofiev.

Joaquin Rodrigo: Cantico de la esposa (Song of the Bride)

Joaquin Rodrigo: Cantico de la esposa (Song of the Bride) Eventually Rodrigo was awarded the “Conde de Cartagena Scholarhip” allowing him to join his wife in Paris. Victoria gave up her career as a pianist to devote all her efforts to the works of her husband, collaborating with him in musical and literary matters. When the scholarship was initially renewed, the couple decided to spend some time in Germany. However, with the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, the scholarship fund was no longer available and they had to find refuge at the Institute for the Blind in Freiburg. Three years of extended hardship finally came to an end in 1939, and Rodrigo completed his most famous composition, the Conceirto de Aranjuez. Victoria writes that shorty after the premiere of the concerto on 9 November 1940, their daughter Cecilia was born. “And what about her eyes?” Victoria asked weakly. “They’re magnificent, blue.”

Eventually Rodrigo was awarded the “Conde de Cartagena Scholarhip” allowing him to join his wife in Paris. Victoria gave up her career as a pianist to devote all her efforts to the works of her husband, collaborating with him in musical and literary matters. When the scholarship was initially renewed, the couple decided to spend some time in Germany. However, with the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, the scholarship fund was no longer available and they had to find refuge at the Institute for the Blind in Freiburg. Three years of extended hardship finally came to an end in 1939, and Rodrigo completed his most famous composition, the Conceirto de Aranjuez. Victoria writes that shorty after the premiere of the concerto on 9 November 1940, their daughter Cecilia was born. “And what about her eyes?” Victoria asked weakly. “They’re magnificent, blue.”