It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Sunday, June 22, 2025

Pachelbel - Canon in D-dur

How Did Pachelbel’s Canon Become So Popular?

by Emily F. Hogstad

But the Canon wasn’t always so famous. For generations, it languished in obscurity, just waiting to be rediscovered.

Today, we’re looking at the life of Johann Pachelbel, his close connection to the Bach family, how his Canon was once lost to history, what it took to be rediscovered, and how pop music helped to cement the Canon’s place in modern pop culture.

The Life of Johann Pachelbel

Johann Pachelbel

Johann Pachelbel was born in September 1653 in Nuremberg.

In 1677, he moved to Eisenach in present-day Germany and took a job as court organist. While there, he met Johann Sebastian Bach’s father and even tutored some of the Bach family children.

The following year, he became an organist in the city of Erfurt. He remained close to the Bachs and continued teaching the kids.

One of his students was Johann Christoph Bach (Johann Sebastian Bach’s oldest brother and his music teacher). This made Pachelbel one of Johann Sebastian Bach’s pedagogical “grandfathers.”

In October 1694, Johann Christoph Bach got married, and he invited Pachelbel to provide the music. It is believed this would have been the only time that Johann Sebastian Bach (who would have been nine) would have had the chance to meet him.

Pachelbel died in 1706.

The Origin of Pachelbel’s Canon

Pachelbel’s most famous work is known today as “Pachelbel’s Canon.”

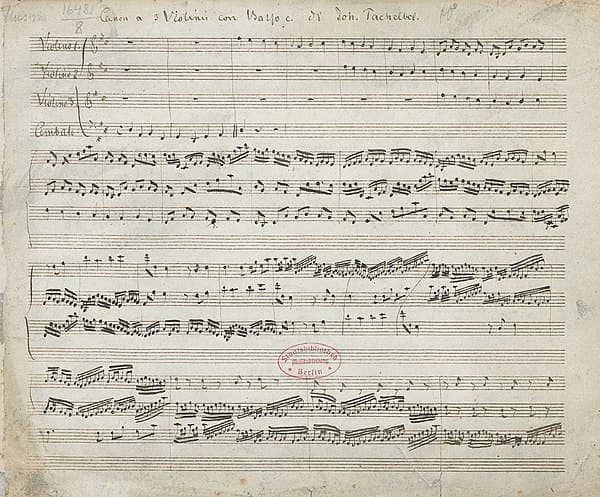

That Canon is part of a larger work, the “Canon and Gigue for 3 violins and basso continuo.”

Johann Pachelbel – Canon and Gigue in D (c. 1700)

Scholars don’t know the exact date of its composition, but believe it was written sometime after 1680.

Some scholars have theorised that it was written for Johann Christoph Bach’s 1694 wedding. It’s a great story, especially since the Canon is so popular at weddings today, but we have no solid proof to back that theory up.

The earliest surviving manuscript version of the Canon and gigue dates from around 1840, long after Pachelbel’s death, so there’s a limited amount that the score can tell us about the work’s origins.

Germany’s Rediscovery of Baroque Music

Fast forward two centuries.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, there was a renewed interest in historical composers, especially in Germany. (Brahms was just one of the German composers who was fascinated and influenced by Baroque music.)

This interest was so strong that in 1912, German composer Max Reger wrote an entire concerto grosso in a Baroque style, calling it his “Concerto in the Old Style.”

Max Reger: Konzert im alten Stil, Op. 123

Clearly, there was persistent – and growing – interest in this era of music. The pump was primed for a work by a Baroque composer like Pachelbel to make a comeback.

Gustav Beckmann’s Rediscovery of Pachelbel’s Canon

Johann Pachelbel’s Canon

Musicologist Gustav Beckmann was born in 1883 in Berlin. He studied philology and musicology, graduating with his doctorate in 1916.

In 1918, Beckmann wrote an article about Pachelbel for a journal called Archive for Musicology, which included the score of Pachelbel’s Canon. The following year, he published the music separately from the article.

In 1929, musicologist Max Sieffert published the score to both the Canon and gigue.

Sieffert included articulation and dynamic markings that Pachelbel had left to the performers’ discretion, making the work more approachable for modern musicians.

The First Recording of Pachelbel’s Canon

The Canon was recorded for the first time in 1938 by violinist Hermann Diener and His Music College.

At the time, Diener was a 41-year-old German violinist.

A few years later, in 1944, Diener would secure a position on Hitler’s famous Gottbegnadeten list (the “God-gifted” list), which listed artists considered vital to upholding Nazi culture. Over 1000 figures were on the list, including Richard Strauss, Carl Orff, and Herbert von Karajan.

The Famous Paillard Pachelbel Recording

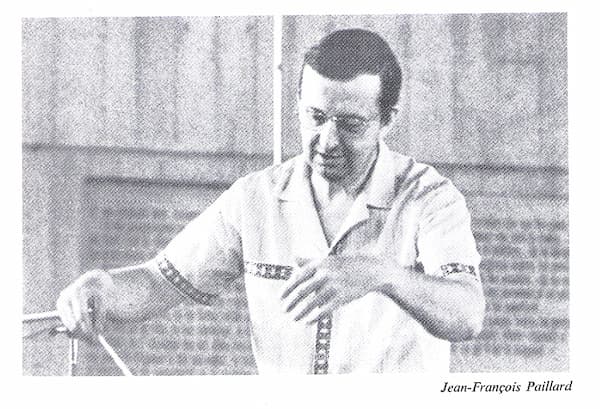

Jean-François Paillard, 1958

Thirty years later, in June 1968, the Jean-François Paillard chamber orchestra recorded a new version of the Canon.

Jean-François Paillard was a French conductor, born in 1928, with a special interest in Baroque repertoire.

This new version boasted a considerably slower tempo from Diener’s recording, and a more sentimental, Romantic style of playing.

Jean-François Paillard: Pachelbel Canon in D major

This version was packaged by the Musical Heritage Society, a mail-order record label that had been founded in 1962. Recordings on this label were sent all around the world, creating a worldwide audience for the work.

Aphrodite’s Child Uses Pachelbel

Almost simultaneously, in July 1968, the Greek band Aphrodite’s Child released a reimagination of Pachelbel’s Canon on a track they called “Rain and Tears.”

Aphrodite’s Child – Rain and Tears

The record became a hit in Europe. Other bands, including Pop-Tops and Parliament, also used the Canon in their own songs between 1968 and 1970.

Pachelbel’s Canon Becomes Famous

The Paillard recording, along with the Canon’s appearance in pop music, kicked off a decade of popularity.

In 1970, a radio station in San Francisco broadcast the Paillard version of the Canon. Local record stores were immediately overrun with music lovers seeking to buy their own recording to have on hand.

Record companies scrambled to issue new recordings. In 1974, London Records reissued an old recording by the Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra from their back catalogue to help meet demand.

In 1979, one record store manager from Philadelphia told Knight-Ridder News, “It sold as well as a major rock album.”

Pachelbel Canon Appears in Pop Culture

In 1980, the piece was prominently featured in the soundtrack for the film Ordinary People, directed by Robert Redford and starring Donald Sutherland and Mary Tyler Moore.

Ordinary People (1980)

In 1980, the Canon appeared in Carl Sagan’s thirteen-part PBS documentary series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, which became one of the most-watched PBS shows of all time.

In 1981, Prince Charles and Princess Diana used the “Prince of Denmark’s March” by composer Jeremiah Clarke as their processional. The Clarke piece was written in 1699, around the same time as Pachelbel’s Canon. This helped to contribute to the popularization of Baroque music, especially at weddings, and meant that Pachelbel’s Canon would be heard more than ever before.

Pachelbel’s Canon Today

Today, Pachelbel’s Canon is one of the most popular pieces of classical music in the world. Some people love it, while others have come to hate it.

Pro-Canon listeners point to its soothing character and joyful connotations with weddings, while anti-Canon listeners point to its repetitive cello part and the way it has oversaturated pop culture.

But whatever you think of Pachelbel’s Canon, it’s undeniable that the resurrection of this obscure piece of Baroque music has made a huge impact on music history.

And one thing’s for sure: that’s an outcome no one in the 1690s could have predicted!

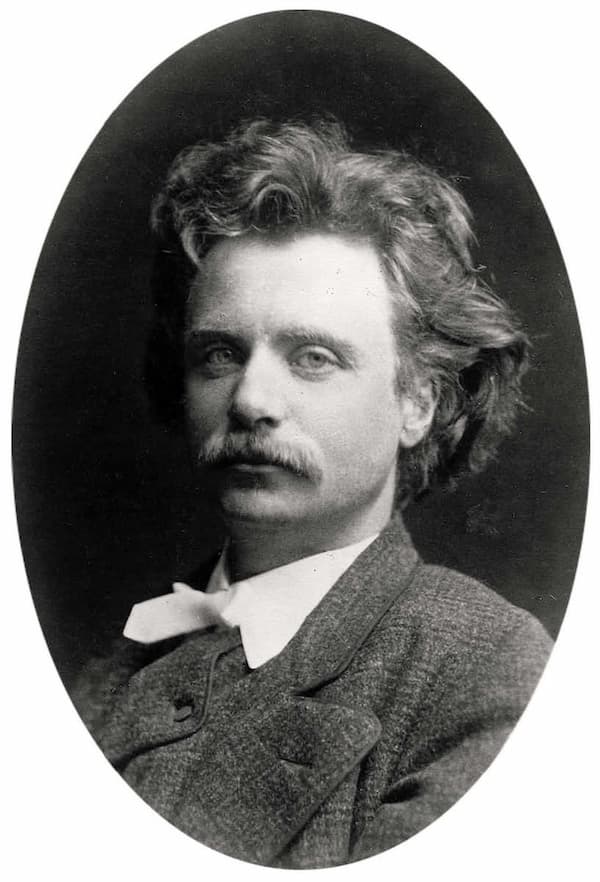

Edvard Grieg’s Greatest Hits - 10 Most Beloved Compositions

by Hermione Lai

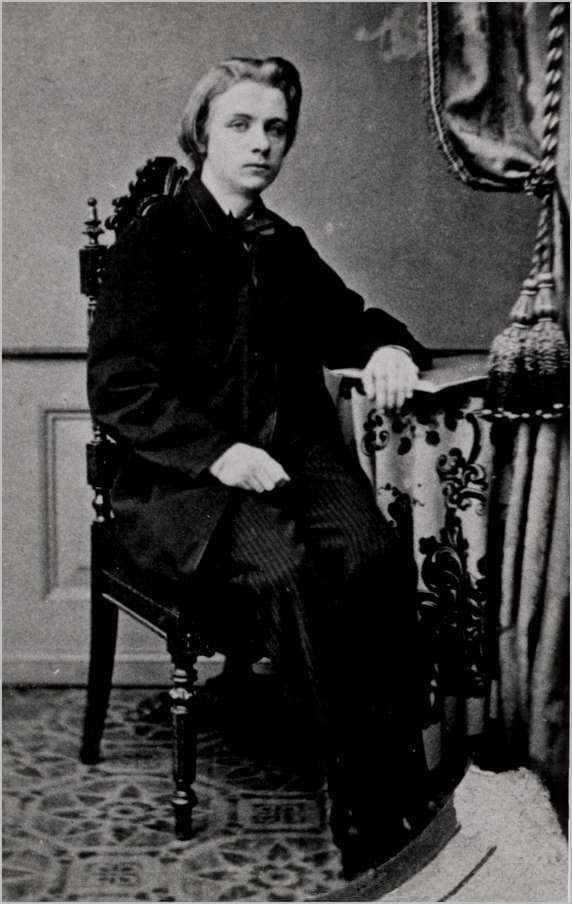

Edvard Grieg, 1858

From the foot-stomping fun of Peer Gynt to the soulful sighs of his Lyric Pieces, we have rounded up the 10 most beloved compositions that will make you yodel in a meadow or waltz with a troll.

If you are ready for a Nordic musical adventure, let’s jump straight in and explore the quirky and catchy genius of Grieg’s greatest hits!

Peer Gynt Suite

It’s only fitting that we start with one of the Peer Gynt Suites. Grieg submerges us into the wild and whimsical world of Henrik Ibsen’s play through his vibrant orchestral music. Composed in 1875, and he did write 2 different suites, Grieg captures the adventurous spirit of the roguish “Peer Gynt.”

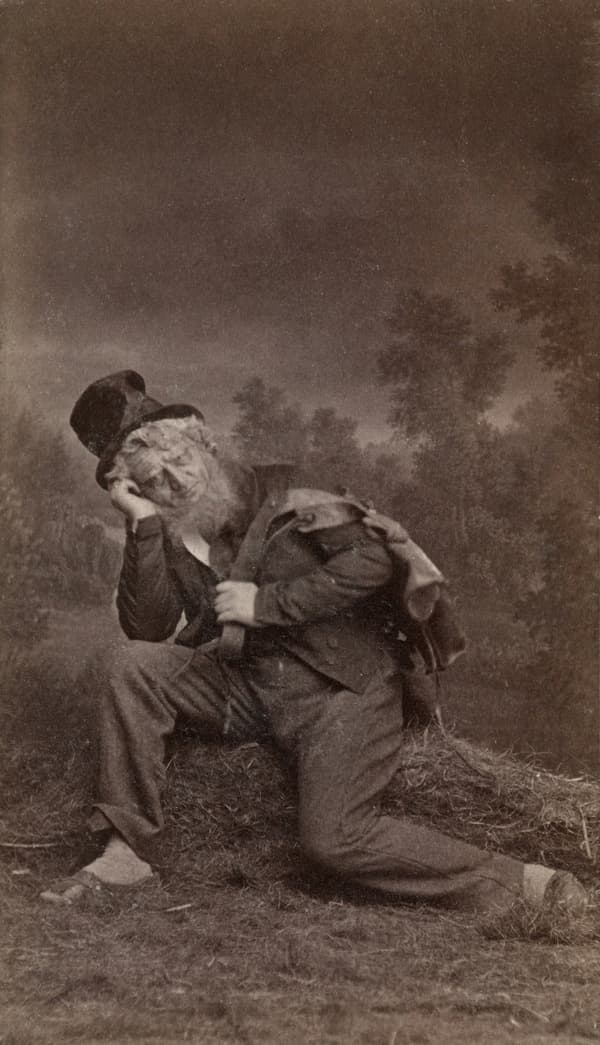

Henrik Klausen as Peer Gynt at Christiania Theater

You surely know such iconic pieces as “Morning Mood,” which paints a serene sunrise, or “In the Hall of the Mountain King,” a thrilling, mischievous romp. Infused with Norwegian folk melodies, these suites are among Grieg’s most beloved works, bursting with drama and charm.

These suites are like a musical Netflix series, each movement a new episode packed with thrills and chills. Whether you’re a classical newbie or a seasoned listener, Peer Gynt is Grieg at his storytelling best.

Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 16

Edvard Grieg cooked up his piano concerto in 1868. This piece is a wild ride, almost like a Nordic roller-coaster that starts with a thundering drumroll and the piano diving in like a Viking raid.

The first movement struts a catchy melody, and Grieg blends stormy passion with moments so tender you’ll want to hug a pine tree.

But the epic doesn’t stop there, with the second movement sounding like a cosy fireside chat, and the third with a dance so lively, you’ll swear you’re at a Scandinavian hoedown. No wonder it’s one of the most famous piano concertos ever.

Holberg Suite

The Holberg Suite is a snappy little number from 1884, that’s basically a love letter to the 18th century, but with a Norwegian twist. Grieg wrote it to celebrate the 200th birthday of Ludvig Holberg, a Danish-Norwegian writer who was like the Shakespeare of Scandinavia.

Originally written for piano, Grieg jazzed it up with strings, giving us five movements that prance around like a Baroque dance party. And the opening “Praeludium” is like a caffeinated squirrel sprinting through a fjord.

The good times keep on rolling with movements like the Sarabande, a Gavotte, and a slow Air, ending with a foot-stomping Rigaudon. Grieg was a genius by taking old-school Baroque vibes and spiking them with his Nordic charm.

Lyric Pieces

Did you know that Grieg wrote 66 short piano works that are like musical selfies of the Norwegian psyche? Each piece paints a mood, with some dreamy, some cheeky, and some vivid like a troll dodging through the forest.

These pieces are Grieg at his most playful, wrapping Nordic folklore, nature, and heart-tugging emotion into mini masterpieces. Whether you’re a beginning pianist or just an appreciative listener, the Lyric Pieces are like a box of musical chocolates.

Every single one is a sweet surprise, and trust me, you’ll want to savour them all.

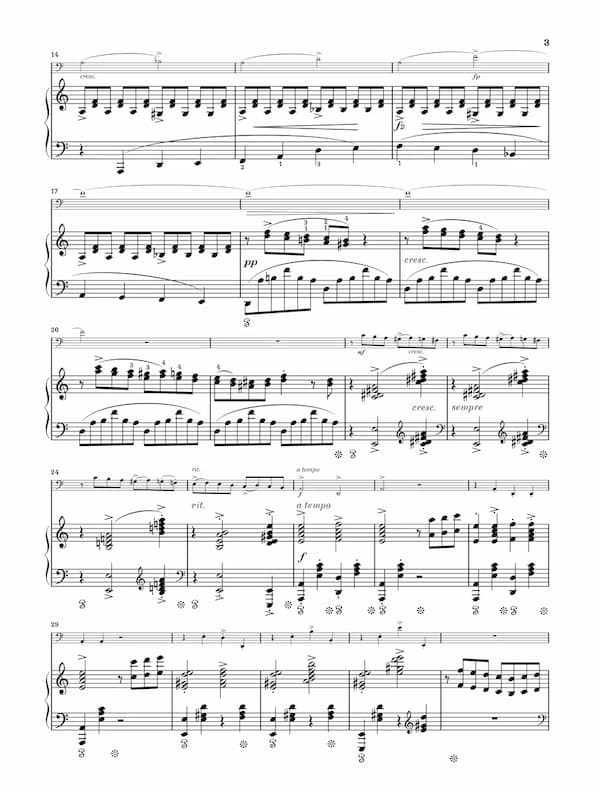

Cello Sonata in A minor, Op. 36

The Grieg Cello Sonata is a masterpiece that’s like a musical bear hug between a cello and a piano. It sounds like Grieg channelled all his passion into this piece, which was actually written for his buddy, the cellist Wilhelm Sinding.

Edvard Grieg’s Cello Sonata

It’s got three movements of pure drama, starting like a Viking longship hitting choppy waters. It’s big and bold with the cello telling a saga of lost love. This is Grieg at his most cinematic, basically composing the soundtrack for a romantic comedy.

The second movement sounds like a cosy fireside chat, and the third crashes in like a Nordic festival. The cello and piano chase each other like kids playing tag in the meadow. This sonata is a rollercoaster that will make you laugh, cry, and maybe even yodel along.

String Quartet No. 1 in G minor, Op. 27

In his first string quartet, Grieg packs an entire Norwegian fjord into four string instruments. It basically sounds like a soap opera for two violins, viola, and cello. The opening movement is highly dramatic, intense, and passionate. It’s full of Grieg’s signature folk-inspired melodies, like a fiddling elf sitting on your shoulder.

Then we find a dreamy and heart-tugging waltz, with strings swaying under the northern lights and whispering sweet nothings to each other. The cheeky little intermezzo sounds like a goat going to a barn dance, and the concluding movement will leave you breathless.

This string quartet shows Grieg at his most adventurous, blending raw emotion with a folky flair, like a musical stew. It’s rich, bold, and totally unforgettable.

Violin Sonata No. 3 in C minor, Op. 45

Here comes another romantic comedy for violin and piano written by Grieg in 1887. His 3rd violin sonata is a masterpiece, a delightful Viking saga with plenty of cheeky charm. It opens with a fiery thunderstorm, the violin belting out a stormy tune and the piano tossing in sparkly chords.

If the opening movement sounds like a Nordic epic, the second will melt your heart. Grieg exchanges his Viking helmet for the beret of a poet. The violin sings a tender lullaby, and the piano sprinkles in delicate notes like fireflies on a summer night.

But don’t get too comfy as the final movement bursts in like a barn dance on caffeine. It’s a Norwegian hoedown for sure, with plenty of foot-tapping energy and a triumphant finish. It’s perfect for classical music fans or anyone ready to fall in love with a fiddle-fuelled adventure.

Haugtussa, Op. 67 (The Mountain Maid)

Grieg’s song cycle Haugtussa, based on poems by Arne Garborg, is like a musical fairy tale. It’s all about a clairvoyant shepherdess named Veslemøy, and in eight songs, Grieg is channelling his inner Nordic mystic into music.

Surrounded by goats and fjords, the dreamy farm girl imagines herself in a magical forest. However, things get juicy, as she falls in love with a hunky farm boy. Sadly, the boy is not really interested, and Veslemøy casts a musical hex.

Grieg’s genius is blending haunting Nordic vibes with catchy folk tunes, making Haugtussa feel like a campfire story told by a bard who’s had too much to drink. This cycle is a quirky emotional ride and ends with the maid finally finding solace in nature.

Ballade in G minor, Op. 24

Composed in 1874-5, the Ballade in G minor is a deeply personal set of variations on a Norwegian folk tune. Don’t be fooled, however, as this is no simple campfire ditty, with the theme rolling in all sombre and brooding.

Grieg then spins the melody into a rollercoaster of moods, from stormy tantrums to twinkly moments that feel like sunlight bouncing off a glacier. As the Ballade rolls on, Grieg flexes his compositional muscle, tossing in variations that range from angry to dreamy.

Written during a tough time in Grieg’s life, as his parents had just passed away, this piece feels like a musical diary. It feels raw and heartfelt, but in the end, it comes to a triumphant if bittersweet conclusion. It certainly is an emotional and wild ride that proves that Grieg could turn a single tune into a complete story.

Four Psalms, Op. 74

Edvard Grieg

Written for mixed choir, Grieg composed his Four Psalms in 1906; they would be his final works. Based on Norwegian hymn tunes, these serene and spiritual pieces radiate simplicity and warmth, with lush harmonies reflecting Grieg’s deep connection to his faith and heritage.

Each psalm has its own flavour and its own personal devotion. With soaring melodies, Grieg dials up the drama, with the set wrapping up with a serene glow, like a lullaby to the stars. These beautiful pieces are raw and heartfelt, blending folk roots with spiritual depth.

It’s a quiet farewell, offering a moving glimpse into the composer’s contemplative side. He captures the essence of each work while keeping the tone approachable and engaging.

Bonus Track: Norwegian Dances, Op. 35

It’s time to wrap up this little feature on the 10 most beloved compositions of Edvard Grieg by featuring his Norwegian Dances, Op. 35. Originally written for piano four-hands, they are a set of four foot-stompers that make you want to grab a partner and twirl through a fjord.

Each dance is a mini-adventure, packed with rustic charm and cheeky energy. They range from flirty waltzes at a village fair to full how-downs, like you’re galloping along like a herd of reindeer on a sugar rush. These Norwegian Dances are a rollicking romp, and you’ll want to two-step around your living room very soon.

Edvard Grieg’s ten most beloved compositions, from the whimsical charm of Peer Gynt to the heartfelt lyricism of his Lyric Pieces, continue to captivate listeners with their vibrant Norwegian spirit and timeless emotional depth. These works not only celebrate his genius but also invite us all to dance, dream, and wander through the enchanting landscapes of his musical imagination.

| |||||||

|

Ten Greatest Women Pianists of All Time

by Emily E. Hogstad, Interlude

So many women have done so that it’s impossible to make an objective list of the ten greatest women pianists of all time.

However, there’s nothing keeping music lovers from creating their own subjective lists.

Here’s one such subjective list, featuring some of the greatest women pianists who were born between 1751 and 1987.

Let us know who would be on your list!

Maria Anna Mozart (1751–1829)

Maria Anna Mozart, nicknamed Nannerl during her childhood, was Wolfgang Amadeus’s older sister.

Their father, Leopold, began teaching her keyboard when she was seven years old. She immediately proved to be a prodigy and was a full-blown virtuoso by eleven.

Maria Anna Walburga Ignatia Mozart by Pietro Antonio Lorenzoni © madamegilflurt.com

When the Mozart family first began touring Europe, Nannerl was initially the bigger draw and was often given top billing over her brother.

During her career, she played for aristocrats and royal families in Austria, Germany, France, Switzerland, and Britain.

After she turned eighteen and became of marriageable age, her family withdrew her from the concert platform. She was forced to watch from the sidelines as Wolfgang continued his travels and musical education in Italy without her.

She married a widowed magistrate in 1784 and moved to a home thirty kilometres from the family hometown of Salzburg. She had three children of her own and also helped to raise her husband’s five children from his previous marriages.

She continued to play the piano for multiple hours a day. Even after her husband died, she continued playing and teaching.

Maria Szymanowska (1789–1831)

Maria Szymanowska was born to a wealthy family in Warsaw in 1789.

We don’t know for sure how she began her musical life, but it seems likely that she studied with Frédéric Chopin’s teacher, Józef Elsner. She gave her first public recitals in 1810, the year of Chopin’s birth.

She also married in 1810 to a man named Józef Szymanowski. They would have three children together, including a set of twins. They separated in 1820.

Maria Szymanowska

Szymanowska made several tours during her marriage, but her touring activities ramped up in the 1820s. During that decade alone, she appeared in Germany, France, Britain, Holland, Belgium, Italy, and Russia.

She composed works for piano that were deeply influenced by her Polish roots. (Some historians have argued that they influenced a young Chopin.) She became a great favorite in musical salons, and many composers dedicated works to her, including Beethoven.

During her visit to St. Petersburg, she was named First Pianist to the Russian Imperial Court. In 1828, she decided to settle in St. Petersburg, but she died in the 1831 cholera epidemic, cutting short a major career.

Clara Wieck Schumann (1819–1896)

Clara Wieck was born in 1819 to piano teacher and music shop owner Friedrich Wieck. As soon as Clara was born, he decided he wanted to mold her into a great piano virtuoso.

Robert and Clara Schumann, 1850

Years of intense study followed. True to Friedrich’s prophecy, Clara proved to be one of the most talented pianists of her generation, male or female.

Her life – and classical music – was changed forever when, in the 1830s, she fell in love with her father’s student Robert Schumann.

Her father protested against the marriage for a variety of reasons, but as soon as she was legally able to, they were married in 1840.

The Schumanns had eight children together, but not even motherhood could keep Clara from continuing her performing career.

After Robert’s mental health collapsed and he died in 1856, Clara continued performing, both out of economic necessity and as a kind of therapy to guide her through her grief.

Throughout her life, she advocated for works by her husband, Chopin, Beethoven, and, perhaps most importantly, Brahms, among many others.

She also reshaped the role of the modern virtuoso, helping to popularize the modern recital format and playing from memory onstage.

Teresa Carreño (1853–1917)

Teresa Carreño was born in Caracas, Venezuela, in 1853.

When she was nine, the family emigrated to New York City, where she began her concert career in earnest. When she was ten, she played for Abraham Lincoln in the White House.

She embarked on her first European tour in 1866. She spent years there, befriending many of the giants of the art: Rossini, Gounod, and Liszt, among others.

Teresa Carreño

In 1873, she married virtuoso violinist Emile Sauret and the following year gave birth to their daughter, Emelita. Sadly, the marriage didn’t last long, and Carreño and Sauret split up.

She would go on to remarry three more times, and have four more children (one of them, Teresita, would become a concert pianist in her own right). Her turbulent love life would become part of her legend.

During the 1870s and 1880s, she spent most of her time touring America, with a couple of trips to Venezuela sprinkled in. In 1889, she returned to Europe to great success. A final large tour to America took place in the 1890s. She died in 1917 in New York City.

Conductor Henry Wood memorably wrote about her:

It is difficult to express adequately what all musicians felt about this great woman who looked like a queen among pianists – and played like a goddess. The instant she walked onto the platform her steady dignity held her audience who watched with riveted attention while she arranged the long train she habitually wore.

Dame Myra Hess (1890–1965)

Myra Hess was born in London in 1890 and began her piano studies at the age of five. She entered the Royal Academy of Music when she was twelve.

She made her orchestral debut when she was seventeen, playing the fourth Beethoven piano concerto under conductor Thomas Beecham.

Myra Hess

Her career plateaued in the late 1910s due to World War I, but she returned to touring as soon as it was over.

However, arguably her greatest artistic triumph happened during World War II, when she organized nearly seventeen hundred concerts over the course of the conflict, playing in 150.

Concert halls had to be blacked out at night to avoid bombing by Nazi planes. So Hess organized lunchtime daytime concerts at the National Gallery in London.

If bombing prevented a performance from taking place, the series would be relocated temporarily, before returning to the gallery.

Over 800,000 people attended her lunchtime concerts, making it one of the most effective morale boosters of the war.

She suffered from a stroke in 1961 and died from a heart attack in 1965.

Alicia de Larrocha (1923–2009)

Alicia de Larrocha was born in 1923 into a family of pianists in Barcelona, Spain. She began studying piano when she was three with teacher Frank Marshall, and gave her first performance when she was five. Marshall would remain her only teacher after the age of three.

She began touring internationally in her mid-twenties and enjoyed a vibrant performing career for decades thereafter.

Alicia de Larrocha

De Larrocha was especially celebrated for her advocacy of Spanish composers like Granados, de Falla, and Albéniz.

But her expertise didn’t stop there: her performances of the Germanic composers like Beethoven, Brahms, Schumann, and Mozart were also highly praised.

She even recorded Liszt, despite the fact that she was less than five feet tall and her hands were small.

She recorded extensively throughout her career and won four Grammy awards between 1975 and 1992.

She retired in 2003 after seventy-five years of public performances. She died in 2009, at the age of 86.

Martha Argerich (1941–)

Martha Argerich was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 1941, to a Spanish-Russian family. She began learning the piano at the age of three and gave her debut concert at the age of eight.

In 1955, when Martha was fourteen, the Argerich family moved to Vienna. She began studying there with iconoclast pianist Friedrich Gulda. Two years later, she won both the Geneva International Music Competition and the Ferruccio Busoni International Competition.

Martha Argerich with The Philadelphia Orchestra, 2008 © carnegiehall.org

Despite her success, she found herself in a musical crisis, and she quit playing for three years. Thankfully, she changed her mind, returning to music, and she won the International Chopin Piano Competition in 1965, when she was twenty-four. It was the kickoff to a decades-long performing career.

In the 1980s, Argerich revealed that performing solo recitals made her feel lonely, so since that time, she has focused on repertoire that includes other musicians, such as concertos and chamber music.

In addition to her storied career as a performing artist, she has worked as a teacher and mentor. She is the president of the International Piano Academy Lake Como and has appeared regularly on competition juries.

As of 2019, at the age of 78, she was still performing the Tchaikovsky piano concerto. As one critic wrote in 2016, “Her playing is still as dazzling, as frighteningly precise, as it has always been; her ability to spin gossamer threads of melody as matchless as ever.”

Mitsuko Uchida (1948–)

Mitsuko Uchida was born outside of Tokyo in 1948. Her family moved to Vienna when she was twelve, and she began studying at the Vienna Academy of Music. She made her recital debut in Vienna at fourteen.

Mitsuko Uchida © Geoffroy Schied

In 1970, when she was twenty-two, she won the second prize in the International Chopin Piano Competition. The prize marked the beginning of a decades-long career.

She has become especially renowned as an interpreter of Mozart. She has recorded all of Mozart’s piano sonatas and concertos, a staggering accomplishment.

If that wasn’t enough, she decided to re-record the Mozart concertos, while also conducting. In 2011, she won a Grammy award for the first record in the series.

She is also famous for being the artistic director at the prestigious Marlboro Music School and Festival, a position she has held since 1999. (She currently shares the position with fellow pianist Jonathan Biss.)

Even today, in her mid-seventies, she is still performing and recording.

Hélène Grimaud (1969–)

Hélène Grimaud was born in 1969 in Aix-en-Provence, France. She began playing the piano at seven.

She began studying at the Paris Conservatoire in 1982 when she was thirteen, and gave her recital debut in Tokyo five years later.

Hélène Grimaud

She gave important debuts with the Berlin Philharmonic in 1995 and New York Philharmonic in 1999.

In 2002, she signed with the prestigious Deutsche Grammophon label, and in the two decades since has released a number of well-received recordings.

She is noted for her wide interests outside of music. She is deeply involved with multiple wildlife conservation efforts and is also a member of Musicians for Human Rights.

She has also written or co-written four books. Her first, Variations sauvages (Wild Variations), published in 2003, is an autobiography. The cover features a photo of her being greeted by three wolves she has met through her wildlife conservation work.

Yuja Wang (1987–)

Yuja Wang was born to a musical family in Beijing in 1987. She began studying piano at the age of six and enrolled at the Beijing Conservatory when she was seven.

Yuja Wang, 2021

When she was fifteen, she moved to Philadelphia to study at the storied Curtis Institute of Music. She studied there with legendary pianist Gary Graffman for five years. We wrote an article about their teacher-student relationship.

She made her European debut in 2003, at the age of sixteen. Her North American debut came two years later.

Her breakthrough performance is widely considered to have happened in March 2007, when she replaced Martha Argerich at the Boston Symphony, playing Tchaikovsky’s first piano concerto.

Since then, she has been in constant demand at the best orchestras and recital venues in the world.

In 2023, she made headlines for performing all four Rachmaninoff piano concertos and his Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini. Ever a fashionista, she changed into a different dress for each concerto. She even played an encore!

In 2012, Joshua Kosman of the San Francisco Chronicle wrote that Yuja Wang is “quite simply, the most dazzlingly, uncannily gifted pianist in the concert world today, and there’s nothing left to do but sit back, listen and marvel at her artistry.”

The words were prophetic. The rich tradition of women pianists – as well as the broader tradition of pianism generally – is in good hands!