by Hermione Lai, Interlude

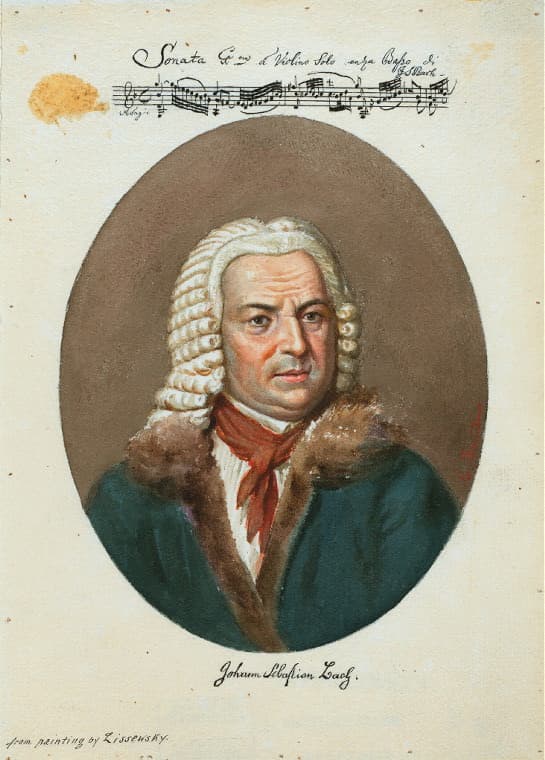

J.S. Bach

Bach’s music has left an indelible mark. From the intricate melodies in his fugues to the emotional depth of his cantatas, Bach’s work pushed the boundaries of what music could express.

Bach’s genius transcends time! His music is a living and breathing testament to the power of creativity and the beauty of sound; they will continue to inspire admiration and awe.

To celebrate his birthday, let’s dive into the wondrous world of his Orchestral Suites, where Baroque brilliance dances with every single note. These timeless masterpieces have enchanted listeners for centuries, and here are the 10 most popular gems that make these suites unforgettable.

Air on a G String (Suite No. 3 in D Major, BWV 1068 “Air”

We just as well get started with one of Bach’s biggest hits ever. The “Air” from his Suite No. 3 is pure and unadulterated musical magic. Many times we see it referenced as “Air on a G String.” That title is not by Bach but comes from an arrangement fashioned in the 19th century.

The soothing and relatively simple melody is one of the composer’s most serene and timeless works. With its hauntingly delicate strings and serene atmosphere, it sounds like a gentle musical embrace.

In Bach’s original version, the piece is typically played on a single string on the violin, and in the lower register. That warm tone is central to the feeling of calm and elegance. The melody unfolds naturally and almost seems to breathe on its own. It transcends time with its graceful simplicity and profound beauty.

Suite No. 2 in B Minor, BWV 1067 “Badinerie”

Bach had this unbelievable genius for turning a simple theme into an unforgettable masterpiece. If you need proof, just listen to the “Badinerie” from his 2nd Orchestral Suite. It is one of his most recognisable and frequently performed compositions.

The title “Badinerie” designates a piece of music light-hearted in character. In French it literally means “jesting,” and Bach presents a vibrant and playful piece characterised by a lively tempo and spirited rhythm.

The melody is primarily carried by the flute and seems almost mischievous at times. It dances through a series of short and rhythmic motifs, and Bach cleverly repeats and transforms these ideas to maintain both interest and drive. It is a masterpiece full of energy and charm and presents Bach’s skill in creating a highly dynamic but intricate musical conversation.

Suite No. 1 in C Major, BWV 1066 “Overture”

One of the all-time Bach favourites, the “Overture” from his 1st Orchestral Suite blends grandeur and elegance in a way that only Bach can. It sets the ceremonial tone for the entire work, and for Bach the title “Overture” generally means “French Overture.”

Musically, that means a slow and majestic introduction followed by a lively and highly contrapuntal section. We can hear the ceremonial dignity in the stately and dotted opening rhythm, but Bach is also building anticipation for the lively section ahead.

Everything starts to dance in the second part, as Bach shifts to a more joyful character with different instrumental voices interacting in lively conversation. The strings lead and create an energetic exchange with the woodwinds and brass. The overture returns to the slow opening rhythm, giving us the impression of having witnessed something noble and celebratory.

Suite No. 3 in D Major, BWV 1068 “Gavotte I & II”

Nobody dances like Johann Sebastian Bach. For some of his most popular examples we don’t need to look further than the Gavotte movements from his 3rd Orchestral Suite. This Gavotte pair reflects the grace of this courtly dance, which Bach infuses with great musical sophistication.

The first “Gavotte” immediately grabs the listener’s attention. The theme is simple, but it feels luxuriously rich due to Bach’s use of harmony and ornamentation. The upbeat rhythm and evenly spaced phrases provide a natural sense of forward motion.

The second “Gavotte” is a bit more reflective, with a slower and more lyrical quality. The musical texture is more transparent with woodwinds and strings creating moments of dialogue. This movement sounds more introspective, yet always retains a feeling of gracefulness. It’s pure Bach, as he blends rhythmic playfulness with harmonic depth and creates timeless delights.

Suite No. 4 in D Major, BWV 1069 “Bourrée I & II” (Cologne Chamber Orchestra; Helmut Müller-Brühl, cond.)

Monument of J.S. Bach in Eisenach, Germany

Bach was the undisputed master of turning simply dance forms into something both dynamic and sophisticated. If you don’t believe me, just take a listen to the pair of Bourrées from the 4th Orchestral Suite.

Bach’s treatment of these fast-paced and duple-time French dances is brimming with infectious energy captured within an intricate musical structure. The first Bourrée opens with a buoyant and immediately recognisable theme. What a sprightly and straightforward melody that gives this dance a playful and almost conversational feel.

The second Bourrée, while still in the same lively spirit, introduces a bit more contrast with a slightly different character. It opens in a similar fashion, with an energetic, clear melody, but there is a subtle shift in tone with the movement feeling slightly more intricate. Although rooted in the tradition of the Baroque dance, Bach is simply genius by elevating a simple form to a level of enduring artistic expression.

Suite No. 2 in B Minor, BWV 1067 “Rondeau”

Let’s next feature another favourite lively and charming dance movement. The “Rondeau” from the 2nd Suite is in a basic rondo structure, where a recurring theme alternates with contrasting episodes. It’s all about creating a sense of continuity and variety.

The “Rondeau” theme is bright, rhythmically energetic, and immediately engaging. We can easily feel the strong dance-like pulse, and a feeling of momentum and lightness. And just listen to that delightful and lively conversation between the strings and the woodwinds.

The contrasting episodes are more lyrical but harmonically more complex. With the string section in the background, the woodwinds are given the opportunity to shine by adding colour and texture. The recurring theme sounds familiar and joyful, while the contrasting episodes offer variety and a touch of elegance.

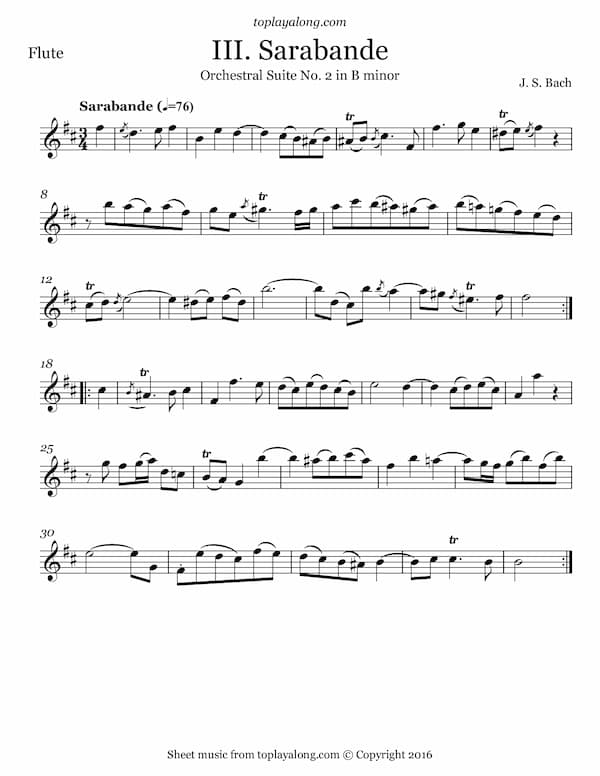

Suite No. 2 in B Minor, BWV 1067 “Sarabande”

J.S. Bach’s Orchestral Suite No. 2 – III. Sarabande

The lively and high-spirited dances in the Bach Orchestral Suites are contrasted by deeply expressive and poignant movements. Such is the case with the “Sarabande,” a slow and elegant dance originating from Spain, from the 2nd Suite.

From the very beginning, this dance radiates a sense of gravity and introspection. In this particular dance the focus falls on the second beat of each measure, creating a slight emphasis. This in turn creates a gentle lilt that drives the movement forward without rushing it.

Bach composes a noble and flowing melody, with long legato phrases providing a vocal-like quality. And astonishingly, every phrase unfolds naturally, inviting the listener into a space of reflection. Bach also adds a harmonically rich tapestry, shifting unhurriedly beneath the long melodic lines. It’s all about the subtle emotional nuances as Bach creates a deeply expressive movement of timeless splendor.

Suite No. 1 in C Major, BWV 1066 “Forlane”

If you’re looking for a sense of joyous celebration, look no further than the “Forlane” from Bach’s Orchestral Suite No. 1. This dance of Italian origin is typically in a moderate 6/8 metre, and Bach uses this basic structure to create a piece full of rhythmic momentum, melodic charm, and intricate phrasing.

While the overall form is straightforward, Bach deliciously propels the music forward by relying on the natural division of each measure into two groups of three beats. The melody is lively and playful, and it dances across the strings using crisp motifs that often occur in the form of a question and answer.

The harmony moves through major keys providing a sense of openness and warmth with occasional slight harmonic surprises. Unexpected modulations or shifts in tonality add a touch of colour and keep the music from becoming predictable. What a perfect and popular example of Bach’s ability to infuse dance music with both vibrancy and grace.

Suite No. 2 in B minor , BWV 1067 “Polonaise”

Johann Sebastian Bach playing the organ, c. 1881

For a beautiful dance of grace and dignity, let’s turn to the “Polonaise” from the 2nd Orchestral Suite. This dance is charming and expressive, with Bach showcasing a graceful melody, elegant ornamentation, rhythmic vitality, and subtle harmonic shifts.

Since it is written in the minor mode, this dance has a slightly sombre and reflective tone. But not to worry as Bach often brightens the mood with delicious modulations and harmonic shifts. The flute plays a key role, presenting the main theme while the string section provides a rich harmonic backdrop.

The rhythmic drive and moderate tempo allow for a stately procession, while the melodies and ornaments provide a sense of joyful elegance. The dance feels lively by capturing both the grandeur of the courtly setting and the joyful spirit of dance. Bach once again blends technical mastery with musical expressiveness.

Suite No. 3 in D Major, BWV 1068 “Gigue”

Every good dance needs a rousing finale, and that’s exactly what we get in the “Gigue” from the 3rd Orchestral Suite. The gigue was a very common dance during the Baroque, and its fast pace and often skipping rhythm reflects the joyful spirit of this particular dance form.

The memorable melody in this dance unfolds in long, flowing phrases that are energetic and graceful. Bach adds a number of ornaments to the lively rhythm to add a layer of expressivity and elegance.

What a fantastic, high-energy movement full of rhythmic complexity and joyful exuberance. And just listen to the marvellous interplay between the instruments to create that sense of dialogue and energy. The music is never standing still, and the same can truly be said of Johann Sebastian’s incredible musical mind.

The Orchestral Suites are a radiant celebration of Bach’s elegance and musical ingenuity. Each suite presents a tapestry of contrasting emotions, weaving together joyous dances, delicate melodies, and intricate counterpoint. Together, they stand as some of the most cherished works in Bach’s orchestral repertoire, leaving us with an uplifting sense of musical fulfillment and joy.