Although it first appeared in the “Agnus Dei” of the Roman Catholic Mass, this plea has travelled far beyond the walls of any church, finding its way into music across centuries and styles.

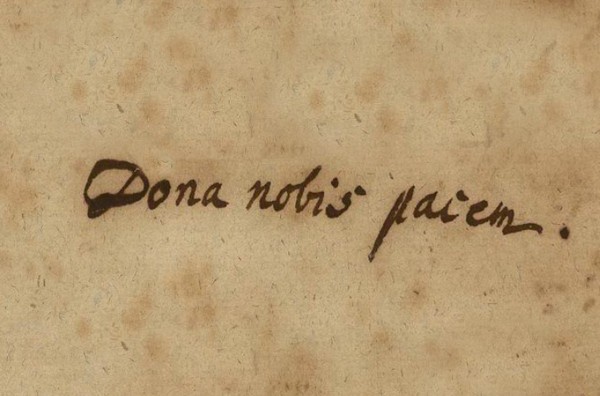

Bach’s writing of “Dona nobis pacem”

From the serene rounds of the medieval era to the soaring polyphony of the Baroque, the impassioned mass settings of the Romantic period, and the stirring cantatas of the twentieth century, composers have returned again and again to this three-word invocation.

It is at once humble and transcendent, a lyrical prayer for our collective hopes, our sorrows, and our longing for a world at rest. As the calendar turns, let us carry “dona nobis pacem” not just as a musical motif, but as a prayer and a promise.

A Single Line

When we look at the diversity of settings, we first look at the dual identities of the text. In fact, it is both a liturgical fragment and a stand-alone musical symbol.

Musically, dona nobis pacem has been composed as a canon, a choral movement within a mass, a large‑scale choral‑orchestral work, and even modern arrangements for handbells and secular choirs.

Through these settings, composers have revealed not only their personal reflections on peace but also the cultural, social, and historical currents that shaped their lives. Each interpretation becomes a mirror of its time. In every era, “Dona nobis pacem” has offered musicians a way to translate human longing into sound.

Statue of Mozart in Salzburg

Maybe the famous “Dona nobis pacem” sound isn’t actually by Mozart, but it captures something people long to associate with Mozart. Clarity without coldness, elegance without effort, and the quiet miracle of voices joining, one after another, to ask for peace.

Two Visions of Peace

Once we move beyond the intimacy of a simple canon, the Renaissance gave “dona nobis pacem” architectural weight and spiritual depth. The plea for peace, as in the masses of Palestrina, is not whispered but carefully built.

The phrase, within the polyphonic Mass, becomes the destination. It is the final space where all preceding musical thought comes to rest. Peace is embodied rather than described, as the music suggests that peace arises through balance, restraint, and communal listening.

For Johann Sebastian Bach, the final “Dona nobis pacem” is both culmination and transformation. The chorus unfolds in dense, purposeful imitation, propelled by orchestral energy, and the prayer expands beyond a personal plea into collective affirmation.

This is peace earned through striving, and order forged from complexity. Where the Renaissance offers calm equilibrium, Bach offers radiant conviction. His vision of peace is not stillness, but moral triumph. It is hard-fought, structured, and ultimately luminous.

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina

Peace as Architecture of Faith

Joseph Haydn

As we move through societal changes and developments, the plea for peace transcends from a communal ritual to an inward, almost existential longing. The words remain the same, but the musical attitude does not. For Joseph Haydn, “dona nobis pacem” belongs to the architecture of faith.

In his late masses, the final Agnus Dei/Dona nobis pacem often begins in gravity or tension and then resolves into buoyant affirmation.

Haydn’s musical language here is public and ceremonial. Rhythmic vitality, clear tonal direction, and bright orchestration suggest peace not as fragile or doubtful, but as something bestowed.

Peace, for Haydn, is communal and stabilising. It belongs to a world where faith, reason, and social order ultimately align. The music reassures, as the pleas for peace have been heard.

The Fragile Plea for Peace

With Mozart, the plea for peace steps out of ceremony and into lived experience. The plea for peace no longer sounds like a confident conclusion to a ritual already understood, but like a moment of exposure.

Rather than pressing toward emphatic resolution, Mozart allows vulnerability to linger. His lines unfold with a natural, almost conversational lyricism, as if the music itself were breathing alongside the listener.

This is peace understood as a moral and human ideal rather than a guaranteed outcome. Peace in this music is not proclaimed, but carefully and almost shyly, offered. His settings acknowledge that peace is something we long for precisely because it is so easily broken.

Mozart’s Enlightenment spirit comes fully into focus. Faith remains, but it is infused with empathy. Even when he writes for grand forces, the plea for peace feels intimate. It is music that does not assume peace as a conclusion, but asks for it gently and earnestly.

The Music of Hesitation

Franz Schubert © Hadi Karimi

Once we make it to Franz Schubert, ” Dona nobis pacem ” has crossed a threshold. In his late masses, the plea no longer feels assured of fulfilment. Schubert often avoids emphatic closure, favouring suspended harmonies, unexpected modulations, and an almost questioning tone.

Schubert’s Dona nobis pacem can feel hesitant, inward, and searching. The music does not declare peace so much as hope for it. The sense of consolation is fragile and provisional. A Romantic consciousness is emerging.

Faith exists, but certainty does not. Peace here is not guaranteed by divine order nor resolved through classical balance. It is something yearned for by an individual soul, aware of loss, mortality, and distance from transcendence.

Schubert turns it inward, allowing doubt and longing to remain unresolved. What begins as a liturgical formula becomes, by Schubert’s time, a mirror of changing human self-understanding. The words never change, but the music tells us that we might never fully possess peace.

A Universal Cry for Peace

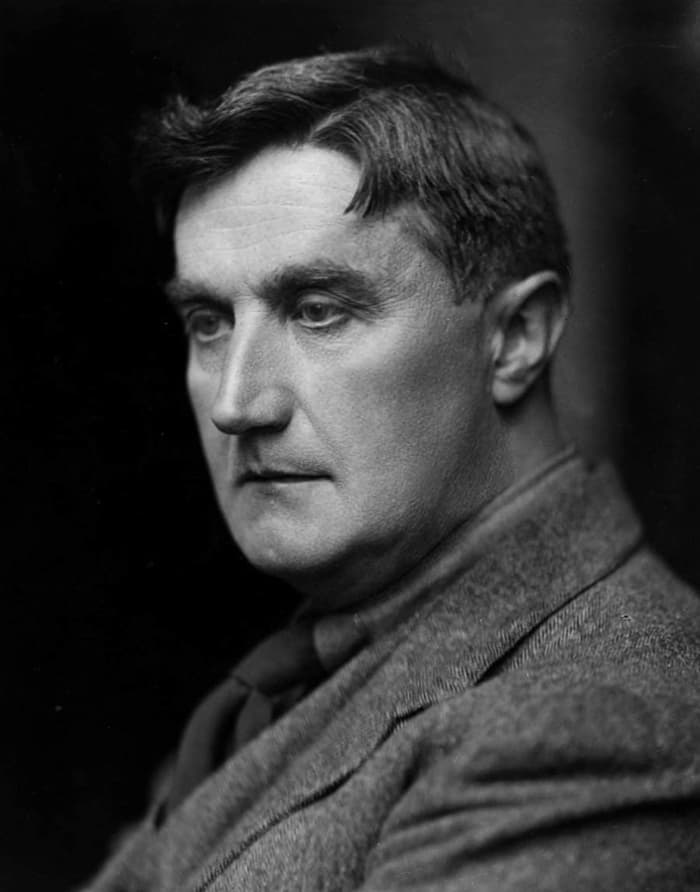

E.O. Hoppé: Vaughan Williams, 1920

While settings throughout the 19th century often remained within liturgical boundaries, the 20th century witnessed a dramatic reimagining of this plea for peace as a large-scale artistic statement about war and peace, reaching far beyond liturgical roots.

Probably the most significant example emerges courtesy of Ralph Vaughan Williams’s 1936 cantata Dona nobis pacem. Commissioned for the centenary of the Huddersfield Choral Society, this work blends the Latin Mass text with poetry by Walt Whitman, Biblical passages, and political speech excerpts to produce a sweeping plea for peace during a period of escalating global tension.

Vaughan Williams’ setting opens with the familiar “Agnus Dei” prayer and then moves into movements based on Whitman’s vivid war poetry, which dramatise the intrusion of war into everyday life and explore the emotional and moral complexities of conflict.

Ultimately, the piece returns to the prayer, asserting peace not merely as a liturgical desire but as a deeply human imperative. The work exemplifies how the theme evolved in modern times. Vaughan Williams transforms a liturgical fragment into a political and emotional epic, situating the plea for peace within a universal conversation about war.

The Enduring Human Plea

In our time, Dona nobis pacem continues to appear in countless settings beyond traditional choral liturgy or large orchestral works. Composers and arrangers have crafted versions for smaller ensembles, educational choirs, and instrumental groups.

Even in secular popular culture, the phrase often appears in contexts divorced from strict liturgy. Its presence in hymnals, children’s choir pieces, and recordings of Christmas and peace songs suggests that Dona nobis pacem has entered the broader cultural imagination as a universal symbol of hope.

Across the centuries, Dona nobis pacem has never belonged to a single style or moment. It has lived as a simple round sung together, as intricate polyphony, as a radiant mass finale, and as an urgent modern cry. Each setting reflects its time, yet all return to the same fragile truth. Peace is never assumed, only asked for.

Perhaps that is why these words continue to move us. In singing “grant us peace”, we hear generations before us voicing the same hope we carry today. Music gives us the hope, if only for a moment, to believe that by listening together, and by singing together, we might edge a little closer to the harmony we so deeply desire.