by

Sometimes composer break out of their box – make a new sound – make you hear music a new way – and sometimes it’s the performers who help as well. Take a listen to these performances and these interesting works from a variety of composers from the Renaissance period to today.

We’re so used to hearing BIG Beethoven. Large chords, rhythms that never seem to end, dramatic statements. But what happens if you change the means of performance? Is this the way you imagined the Moonlight Sonata?

© Wikipedia

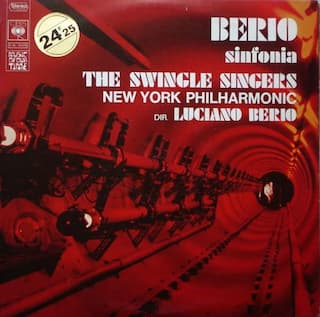

Luciano Berio was commissioned by the New York Philharmonic for a work for its 125th anniversary, for its 1968-69 season. He gave them Sinfonia, for orchestra and 8 amplified voices, to create not a history of music, but a distorted history of culture. The third movement is a mélange of musical quotation and text quotations. The movement starts with extensive quotations from Mahler’s Symphony No. 2, a composer championed by Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic. The orchestra also plays ‘snatches of Claude Debussy’s La mer, Maurice Ravel’s La valse, Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, as well as quotations from Arnold Schoenberg, Anton Webern, Johannes Brahms, Henri Pousseur, Paul Hindemith, and many others (including Berio himself)…’.The voices recite texts by Samuel Beckett, James Joyce, stage directions, with the original word sometimes changed or juxtaposed with other texts.

We all know the third movement of Chopin’s Piano Sonata No. 2. It’s the somber Marche funebre. A funeral march at a Lento speed. What may not be so familiar is the next movement. The speed is Presto, the touch is legato, the dynamics muted, and the notes unceasing until the final note, which strikes, as a writer said, as a ‘blow from the executioner’s axe’.

One work that on first hearing you’d have a hard time to even place it with the correct composer, let alone get the date of composition correct, is Maurice Ravel’s 1918 work for piano, Frontispice (Frontispiece). It’s for 2 pianos, but 2 pianos and 5 hands. The two pianos are in different meters: piano 1 starting in 15/8 and Piano 2 enters one measure later in 5/4. The pianos provide overlapping melodic lines that are completely independent. The piece was written as a prelude to a reading of Ricciotto Canudo’s poem S.P. 503 Le poème de Vardar, where the author reflects on his war experiences.

We know Liszt: bravura piano music, melodically driven, constantly innovating, and then when we look at his Bagatelle sans tonalite, S. 216a (earlier titles included Bluette fantasque and Mephisto Walzer Nr. 4 (ohne Tonart), we have a work of ambiguous harmony. There are echoes of the earlier Mephisto Waltzes, but this seems to remain outside – almost a commentary on his own work.

Can you guess what unusual sound generator is used at the beginning of Arvo Pärt’s Symphony No. 2?

Yes, those were rubber ducks, and later, there’s crackling cellophane paper. Written in 1966, this work was part of Pärt’s early serialist style.

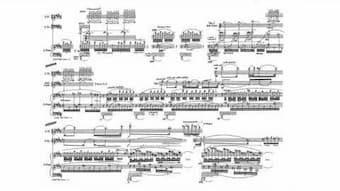

George Crumb: Vox Balaenae score © FANDOM Music Community

American composer George Crumb was inspired by one of the largest animals on Earth for this work from 1971. Vox Balaenae (Voice of the Whale) requires the players to be anonymized by wearing black half-masks through their performance. Written for amplified flute, cello, and piano, the work requires that the flautist both plays and sings at the same time, and the cellist uses glissandos in an ultra-high register to imitate the cries of seagulls.

Dowland’s lute music set the style for the English court – melancholic but always melodic. We somehow always imagine these as somewhat dry pieces, performed by a lutenist to himself as his best audience. However, in one work, he guaranteed that the performer would be able to get as close as possible to his audience. His work, My Lord Chamberlain, His Galliard, was published in his First Book of Songs in 1597. This work is written for 1 lute, but two performers (or in piano-speak: 1 lute, 4 hands.

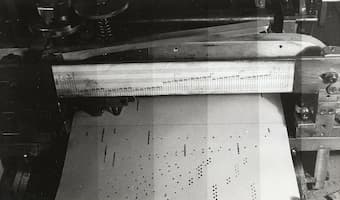

Conlon Nancarrow: Player Piano © Whitney Museum of American Art

What happens when you have a vision for the music you want to play but it’s literally impossible for a single person with two hands and 10 fingers to play? For American composer Conlon Nancarrow, he transferred his music from a regular piano to a player piano. Mixed time signatures? No problem. Notes that are impossibly fast? No problem. More than 10 keys being played at once? No problem.

The composer and humourist Peter Schickele, in his manifestation as P.D.Q. Bach (the oddest of J.S. Bach’s 20-odd children), gave us a work that is almost too familiar to talk about, but in presenting it with the vapid commentary of a baseball game, gave us a different way to hear Beethoven. It’s a legitimate analysis, with all the familiar sports metaphors, but with a commentary that doesn’t miss a note.

Music – we have lots of way of appreciating it – sometimes seriously, sometimes with humour – but always with an understanding that there’s lots of it out there to discover!

No comments:

Post a Comment