It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Sunday, June 22, 2025

Music's Impact: Emotions, Brain, and Culture (III)

Filipino music in general was introduced to me by my wife Rossana. What does music really mean to Filipinos? It simply tells them where they've been and where they could go. It tells a story that everyone can appreciate and relate to, which is why it's a big part of every Filipino culture.

During the 1980s, Rossana was the lead dancer of the Manisan Cultural Dance Troupe. I got to know about gong music which can be divided into two types: the flat gong commonly known as gangsà and played by the groups in the Cordillera region and the bossed gongs played among the Islam and animist groups in the southern Philippines. The kulintang ensemble is the most advanced form of ensemble music with origins in the pre-colonial epoch of Philippine history and is a living tradition in southern parts of the country.

Very quickly, it pleased me another popular medium for light classical muse - the rondalla. Its repertoire consists mainly of native folk tunes, ballroom music as well as arrangements of classical pieces such as opera overtures. Bayani de Leon and Jerry Dadap have written more serious music for the rondalla. Rondalla is a traditional string orchestra comprising two-string, mandolin-type instruments such as the banduria and laud; a guitar; a double bass; and often a drum for percussion. The rondalla has its origins in the Iberian rondalla tradition and is used to accompany several Hispanic-influenced song forms and dances.

Tinikling and Cariñosa inspired me more and more. The Tinikling is a dance from Leyte which involves two individual performers hitting bamboo poles, using them to beat, tap, and slide on the ground, in coordination with one or more dancers who step over and in between poles. It is one of the more iconic Philippine dances and is similar to other Southeast Asian bamboo dances. The Cariñosa (meaning "loving" or "affectionate one") is the national dance and is part of the María Clara suite of Philippine folk dances. It is notable for the use of a fan and handkerchief in amplifying romantic gestures expressed by the couple performing the traditional courtship dance. The dance is similar to the Mexican Jarabe Tapatío, and is related to the Kuracha, Amenudo, and Kuradang dances in the Visayas and Mindanao Area.

In the first few years of my life as an expat in the Philippines, it looked like I had forgotten about my classical music from Europe. I focused more and more on Himig ng Pilipinas - the musical performance arts in the Philippines or by Filipinos composed in various genres and styles. The compositions are often a mixture of different Asian, Spanish, Latin American, American, and indigenous influences.

Notable folk song composers include the National Artist for Music Lucio San Pedro, who composed the famous "Sa Ugoy ng Duyan" that recalls the loving touch of a mother to her child. Another composer, the National Artist for Music Antonino Buenaventura, is notable for notating folk songs and dances. Buenaventura composed the music for "Pandanggo sa Ilaw".

The leading figures of the first generation of Philippine composers were Nicanor Abelardo, Francisco Santiago, Aontonio Molina, and Juan Hernandez.

But one composer and his works fascinated me the most: Francisco Buencamino. He belonged to a family of musicians. He was born in San Miguel de Mayumo, Bulacan, on November 5, 1883. In 1930, he founded the Academy of Music of Buencamino. His musical styles were Kundimans and Sarzuela.

Francisco first learnt music from his father. At age 12, he could play the organ. At 14, he was sent to study at the Liceo de Manila. There, he took up courses in composition and harmony under Marcelo Adonay. He also took up piano-forte courses under a Spanish music teacher. He did not finish his education as he became interested in the sarswela. Some of the sarswelas he wrote are: "Marcela" (1904), "Si Tio Celo" (1904) and "Yayang " (1905). In 1908, the popularity of the sarswela started to wane because of American repression and the entry of silent movies. Francisco Buencamino then turned to composing kundimans.

For a time, Francisco Buencamino frequently acted on stage. He also collaborated on the plays written and produced by Aurelio Tolentino. One of his earliest compositions is "En el bello Oriente" (1909), which uses Jose Rizal's lyrics. "Ang Una Kong Pag-ibig", a popular kundiman, was inspired by his wife. In 1938, he composed an epic poem which won a prize from the Far Eastern University during one of the annual carnivals. His "Mayon Concerto" is considered his magnum opus. Begun in 1943 and finished in 1948, "Mayon Concerto" had its full rendition in February 1950 at the graduation recital of Rosario Buencamino at the Holy Ghost College. "Ang Larawan" (1943), also one of his most acclaimed works, is a composition based on a Balitaw tune. The orchestral piece, "Pizzicato Caprice" (1948) is a version of this composition. Many of his other compositions were lost during the Japanese Occupation, when he had to evacuate his family to Novaliches, Rizal.

I would say that the "Pizzicato Caprice" is my favorite. I was so lucky to experience it during an awesome performance with the Manila Symphony Orchestra.

In my opinion: outstanding groups include not only the Manila Symphony Orchestra, but also the Filipino Youth Symphony Orchestra, the U.P. Symphony Orchestra, the Manila Concert Orchestra, the Quezon City Philharmonic Orchestra, the Artists’ Guild of the Philippines, the Philippine Choral Society, the U.P. Madrigal Singers, the U.P. Concert Chorus among others.

These are extraordinary treasures of Filipino culture which one hears and experiences far too little about these days.

The music of my life started at the age of 6. During my first steps on the piano with Beethoven's "Für Elise", I remember my very first LP (Long Play) on my birthday gifts table: Serge Prokofieff's ' "Peter and the wolf".

In an autobiographical sketch, the Russian composer described the three chief qualities of his complex work as: a classical or rather classicist rendencityan emotional vein and grotesque element, which the composer detected as "fun, laughter, satire". "A symphonic tale for children '' awoke my dream of classical music.

In spite of this drastic sound-painting portrayal, the general effect produced is not that of a musical jest, but - thanks to Prokofieff's artistry and skill - one of singular poetry.

There are few musicians with such eloquence and improvisational skills as Sergei Prokofieff, the Russian composer of many different talents, some of which included the piano and keyboards. Born to a financially well-off family in 1891, Prokofieff’s first exposure to music was through his mother, who would spend two months a year learning the piano while also playing a few sonnets every evening. Prokofiff began learning the piano instantly, and became so proficient that he was then composing his first piano composition, under the watchful supervision of his mother. Before the age of 10, he had also shown interest in opera music and started work on his first opera, called The Giant.

In his early years, Prokofieff’s parents were adamant on providing him with theory lessons, so as to clarify his conceptual frameworks as far as the piano and composition went. However, they soon began having second thoughts about their young son pursuing a music career at such a delicate age, and therefore, decided to enroll him in the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. Here, he worked and learned the piano and other instruments under the auspices of renowned composers such as Alexander Winkler, Nikolai Tcherepnin and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. Before his father’s death in 1910, he had started performing in local clubs and other music venues like the St. Petersburg Evenings of Contemporary Music, performing some of his early Piano Sonatas such as Four Etudes for Piano, Op 2(1909). All through the early 1910s, Prokofieff had been experimenting with a wide variety of genres, one of which was ballet music. While he may have succeeded in a number of other music compositions, he always seems to have a hard time with ballet music, with the likes of Chout becoming subject to intense modifications in the 1920s.

Having received menial works in the 1930s due to the Great Depression, Prokofieff decided to move to Russia in 1936. The period post-1936 was a completely different time for Prokofieff, and set in motion some of his most impressive works. Bearing in mind the hostile reality of the time, most of the themes covered in his works such as his orchestral piece Russian Overture (1936) and War Sonatas embraced war-related topics and disregarded true musical passion. However, Prokofiev managed to retain his incredible ingenuity with compositions such as Peter and the Wolf, Alexander Nevsky and Romeo and Juliet, all of which were received well on an international scale. Some of these compositions were Sergei Prokofiev’s most valuable works, and are still widely performed today.

The war and post-war years saw the likes of some impressive compositions, such as War and Peace, The Ballet Cinderella and various violin sonatas, encompassing the true remarkability that Prokofieff deserves large-scale appraise for. It becomes important to realize the tremendous contributions this great artist made to the classical music world, despite the troubles he so often had to face.

Because of Prokofieff, my world of classical music first opened up to Russia. Yes, not to Germany or Austria. Not to (sorry Maestro!) Beethoven or Liszt, Mozart or whomever. Suddenly, fell in love with Tschaikowsky. His first piano concerto in b-minor kept me speechless and full of tears at any stage play, I was blessed during my whole life.

The very first bars of this piano concerto are so distinctive that they will remain in the listener's memory forever. Tchaikovsky's Piano Concerto No. 1 is recognizable and catchy. Charismatic piano virtuoso Martha Argerich lends an elegant lightness to this impressive piece. Conducted by Charles Dutoit, Argerich performed with the Verbier Festival Orchestra at the Verbier Festival in 2014.

(To be continued!)

(To be continued)

[Nicanor Abelador]

[Francisco Santiago]

[Juan Hernandez]

Filipino music in general was introduced to me by my wife Rossana. What does music really mean to Filipinos? It simply tells them where they've been and where they could go. It tells a story that everyone can appreciate and relate to, which is why it's a big part of every Filipino culture.

Notable folk song composers include the National Artist for Music Lucio San Pedro, who composed the famous "Sa Ugoy ng Duyan" that recalls the loving touch of a mother to her child. Another composer, the National Artist for Music Antonino Buenaventura, is notable for notating folk songs and dances. Buenaventura composed the music for "Pandanggo sa Ilaw".

The leading figures of the first generation of Philippine composers were Nicanor Abelardo, Francisco Santiago, Aontonio Molina, and Juan Hernandez.

In my opinion: outstanding groups include not only the Manila Symphony Orchestra, but also the Filipino Youth Symphony Orchestra, the U.P. Symphony Orchestra, the Manila Concert Orchestra, the Quezon City Philharmonic Orchestra, the Artists’ Guild of the Philippines, the Philippine Choral Society, the U.P. Madrigal Singers, the U.P. Concert Chorus among others.

The music of my life started at the age of 6. During my first steps on the piano with Beethoven's "Für Elise", I remember my very first LP (Long Play) on my birthday gifts table: Serge Prokofieff's ' "Peter and the wolf".

In his early years, Prokofieff’s parents were adamant on providing him with theory lessons, so as to clarify his conceptual frameworks as far as the piano and composition went. However, they soon began having second thoughts about their young son pursuing a music career at such a delicate age, and therefore, decided to enroll him in the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. Here, he worked and learned the piano and other instruments under the auspices of renowned composers such as Alexander Winkler, Nikolai Tcherepnin and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. Before his father’s death in 1910, he had started performing in local clubs and other music venues like the St. Petersburg Evenings of Contemporary Music, performing some of his early Piano Sonatas such as Four Etudes for Piano, Op 2(1909). All through the early 1910s, Prokofieff had been experimenting with a wide variety of genres, one of which was ballet music. While he may have succeeded in a number of other music compositions, he always seems to have a hard time with ballet music, with the likes of Chout becoming subject to intense modifications in the 1920s.

Having received menial works in the 1930s due to the Great Depression, Prokofieff decided to move to Russia in 1936. The period post-1936 was a completely different time for Prokofieff, and set in motion some of his most impressive works. Bearing in mind the hostile reality of the time, most of the themes covered in his works such as his orchestral piece Russian Overture (1936) and War Sonatas embraced war-related topics and disregarded true musical passion. However, Prokofiev managed to retain his incredible ingenuity with compositions such as Peter and the Wolf, Alexander Nevsky and Romeo and Juliet, all of which were received well on an international scale. Some of these compositions were Sergei Prokofiev’s most valuable works, and are still widely performed today.

The war and post-war years saw the likes of some impressive compositions, such as War and Peace, The Ballet Cinderella and various violin sonatas, encompassing the true remarkability that Prokofieff deserves large-scale appraise for. It becomes important to realize the tremendous contributions this great artist made to the classical music world, despite the troubles he so often had to face.

[Nicanor Abelador]

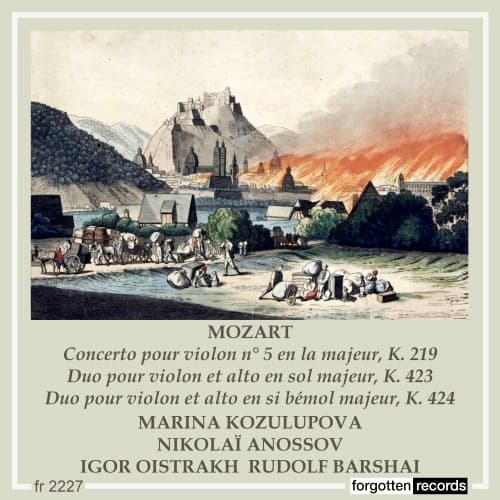

Writing in a Rush: Mozart’s Turkish Violin Concerto No. 5

by Maureen Buja

Anonymous: Wolfgang Amadé Mozart with a diamond ring, gift of Maria Theresa, ca 1775 (Internationale Stiftung Mozarteum)

Mozart’s concertos are built on dialogues – a constant conversation between the soloist and the orchestra. This is true of his piano concertos as of his violin concertos. Most follow the same pattern: in the first movement, the orchestra presents most (but not all) of the thematic material with an additional theme being left for the soloist to present. The first movements, in sonata-allegro form, also have short development sections, but ones that can be full of surprises in terms of harmonies and themes. Themes may vanish for the development section, only to reemerge in the recapitulation to a greater effect.

Slow movements are built around long, singing, and often complex melodies. The soloist takes the fore, but the orchestra still has a valuable role to play, particularly in the development sections.

The rondo finales are where Mozart lets himself loose. Dance music of the day is used, or perhaps even a traditional melody (Violin Concerto No. 3 introduces a melody called the Straßburger) and in the fifth concerto, an ordinary minuet is disrupted by a Turkish dance scene. One writer referred to these as ‘burlesque inserts’ and saw them as appropriate for the Salzburg scene but not the more refined Parisian music scene. The interjection of the ‘temperamental and gruff’ in a minor key really breaks up the introspection of the minuet.

The Turks had first menaced Vienna in 1529, in their first unsuccessful siege of the city, which was barely defeated by the Viennese. Winter and epidemics helped to defeat the besieging Turks. The Second Turkish Siege of 1683 held Vienna in thrall for 2 months, until the Polish army under King John III Sobieski pushed the Turks out again. The Ottoman wars with southern Europe (Venice and Vienna included) didn’t end until the early 18th century. Although Mozart was writing some 60 years later, the Turks were still a concept to be reconciled with, albeit perhaps only as an uncultured figure of fun, here interrupting a civilised minuet.

These works are Mozart’s last compositions as a violinist. Following this, the new fortepiano caught his attention, and he changed instruments. At one point, in discussing a return to Salzburg, he made it a condition to return as a keyboardist and not a violinist.

This recording was made in 1952, with Marina Kozulupova as soloist, performing with the Soviet State Orchestra under Nikolaï Anossov.

Marina Kozulupova (1918–1978)

Russian violinist Marina Semyonovna Kozolupova studied at the Moscow Conservatory and, in 1937, was awarded fifth prize at the International Ysaÿe Violin Competition in Brussels. She’s noted for her recordings of Beethoven and Bach. She taught at the Moscow Conservatory and became a professor there in 1967.

Nikolai Pavlovich Anosov

Russian conductor Nikolai Pavlovich Anosov (1900–1962) also studied at the Moscow Conservatory, although as an external student in composition. He made his debut as a conductor in 1930 and was active in more remote parts of the Soviet Union, being chief conductor of the Rostov Philharmonic Orchestra (1938–1939) and the Baku Philharmonic (1939–1940). In addition, during these years, he taught at the Azerbaijan Conservatory. Finally, he returned to Moscow in 1940 and taught opera and symphony conducting at the Moscow Conservatory. One of his students was his son, Gennady Rozhdestvensky. He was an active promoter of 20th-century foreign music and Russian music of the 18th and 19th centuries.

Performed by

Marina Kozulupova

Nikolaï Anossov

Soviet State Orchestra

Recorded in 1952

Official Website

Pachelbel - Canon in D-dur

How Did Pachelbel’s Canon Become So Popular?

by Emily F. Hogstad

But the Canon wasn’t always so famous. For generations, it languished in obscurity, just waiting to be rediscovered.

Today, we’re looking at the life of Johann Pachelbel, his close connection to the Bach family, how his Canon was once lost to history, what it took to be rediscovered, and how pop music helped to cement the Canon’s place in modern pop culture.

The Life of Johann Pachelbel

Johann Pachelbel

Johann Pachelbel was born in September 1653 in Nuremberg.

In 1677, he moved to Eisenach in present-day Germany and took a job as court organist. While there, he met Johann Sebastian Bach’s father and even tutored some of the Bach family children.

The following year, he became an organist in the city of Erfurt. He remained close to the Bachs and continued teaching the kids.

One of his students was Johann Christoph Bach (Johann Sebastian Bach’s oldest brother and his music teacher). This made Pachelbel one of Johann Sebastian Bach’s pedagogical “grandfathers.”

In October 1694, Johann Christoph Bach got married, and he invited Pachelbel to provide the music. It is believed this would have been the only time that Johann Sebastian Bach (who would have been nine) would have had the chance to meet him.

Pachelbel died in 1706.

The Origin of Pachelbel’s Canon

Pachelbel’s most famous work is known today as “Pachelbel’s Canon.”

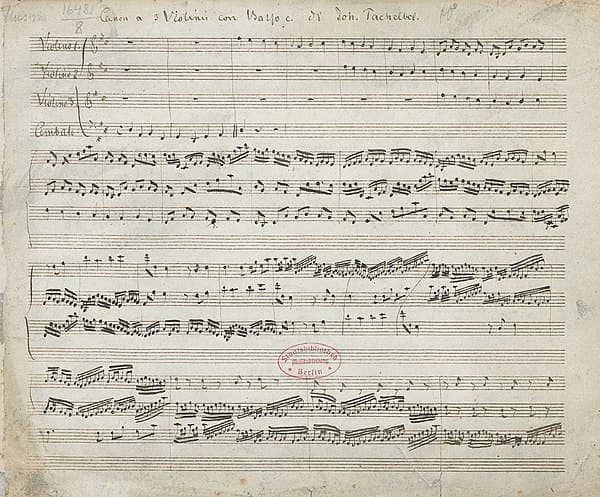

That Canon is part of a larger work, the “Canon and Gigue for 3 violins and basso continuo.”

Johann Pachelbel – Canon and Gigue in D (c. 1700)

Scholars don’t know the exact date of its composition, but believe it was written sometime after 1680.

Some scholars have theorised that it was written for Johann Christoph Bach’s 1694 wedding. It’s a great story, especially since the Canon is so popular at weddings today, but we have no solid proof to back that theory up.

The earliest surviving manuscript version of the Canon and gigue dates from around 1840, long after Pachelbel’s death, so there’s a limited amount that the score can tell us about the work’s origins.

Germany’s Rediscovery of Baroque Music

Fast forward two centuries.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, there was a renewed interest in historical composers, especially in Germany. (Brahms was just one of the German composers who was fascinated and influenced by Baroque music.)

This interest was so strong that in 1912, German composer Max Reger wrote an entire concerto grosso in a Baroque style, calling it his “Concerto in the Old Style.”

Max Reger: Konzert im alten Stil, Op. 123

Clearly, there was persistent – and growing – interest in this era of music. The pump was primed for a work by a Baroque composer like Pachelbel to make a comeback.

Gustav Beckmann’s Rediscovery of Pachelbel’s Canon

Johann Pachelbel’s Canon

Musicologist Gustav Beckmann was born in 1883 in Berlin. He studied philology and musicology, graduating with his doctorate in 1916.

In 1918, Beckmann wrote an article about Pachelbel for a journal called Archive for Musicology, which included the score of Pachelbel’s Canon. The following year, he published the music separately from the article.

In 1929, musicologist Max Sieffert published the score to both the Canon and gigue.

Sieffert included articulation and dynamic markings that Pachelbel had left to the performers’ discretion, making the work more approachable for modern musicians.

The First Recording of Pachelbel’s Canon

The Canon was recorded for the first time in 1938 by violinist Hermann Diener and His Music College.

At the time, Diener was a 41-year-old German violinist.

A few years later, in 1944, Diener would secure a position on Hitler’s famous Gottbegnadeten list (the “God-gifted” list), which listed artists considered vital to upholding Nazi culture. Over 1000 figures were on the list, including Richard Strauss, Carl Orff, and Herbert von Karajan.

The Famous Paillard Pachelbel Recording

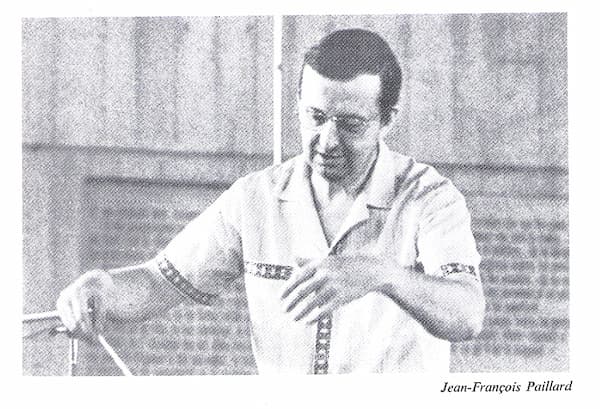

Jean-François Paillard, 1958

Thirty years later, in June 1968, the Jean-François Paillard chamber orchestra recorded a new version of the Canon.

Jean-François Paillard was a French conductor, born in 1928, with a special interest in Baroque repertoire.

This new version boasted a considerably slower tempo from Diener’s recording, and a more sentimental, Romantic style of playing.

Jean-François Paillard: Pachelbel Canon in D major

This version was packaged by the Musical Heritage Society, a mail-order record label that had been founded in 1962. Recordings on this label were sent all around the world, creating a worldwide audience for the work.

Aphrodite’s Child Uses Pachelbel

Almost simultaneously, in July 1968, the Greek band Aphrodite’s Child released a reimagination of Pachelbel’s Canon on a track they called “Rain and Tears.”

Aphrodite’s Child – Rain and Tears

The record became a hit in Europe. Other bands, including Pop-Tops and Parliament, also used the Canon in their own songs between 1968 and 1970.

Pachelbel’s Canon Becomes Famous

The Paillard recording, along with the Canon’s appearance in pop music, kicked off a decade of popularity.

In 1970, a radio station in San Francisco broadcast the Paillard version of the Canon. Local record stores were immediately overrun with music lovers seeking to buy their own recording to have on hand.

Record companies scrambled to issue new recordings. In 1974, London Records reissued an old recording by the Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra from their back catalogue to help meet demand.

In 1979, one record store manager from Philadelphia told Knight-Ridder News, “It sold as well as a major rock album.”

Pachelbel Canon Appears in Pop Culture

In 1980, the piece was prominently featured in the soundtrack for the film Ordinary People, directed by Robert Redford and starring Donald Sutherland and Mary Tyler Moore.

Ordinary People (1980)

In 1980, the Canon appeared in Carl Sagan’s thirteen-part PBS documentary series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, which became one of the most-watched PBS shows of all time.

In 1981, Prince Charles and Princess Diana used the “Prince of Denmark’s March” by composer Jeremiah Clarke as their processional. The Clarke piece was written in 1699, around the same time as Pachelbel’s Canon. This helped to contribute to the popularization of Baroque music, especially at weddings, and meant that Pachelbel’s Canon would be heard more than ever before.

Pachelbel’s Canon Today

Today, Pachelbel’s Canon is one of the most popular pieces of classical music in the world. Some people love it, while others have come to hate it.

Pro-Canon listeners point to its soothing character and joyful connotations with weddings, while anti-Canon listeners point to its repetitive cello part and the way it has oversaturated pop culture.

But whatever you think of Pachelbel’s Canon, it’s undeniable that the resurrection of this obscure piece of Baroque music has made a huge impact on music history.

And one thing’s for sure: that’s an outcome no one in the 1690s could have predicted!

Edvard Grieg’s Greatest Hits - 10 Most Beloved Compositions

by Hermione Lai

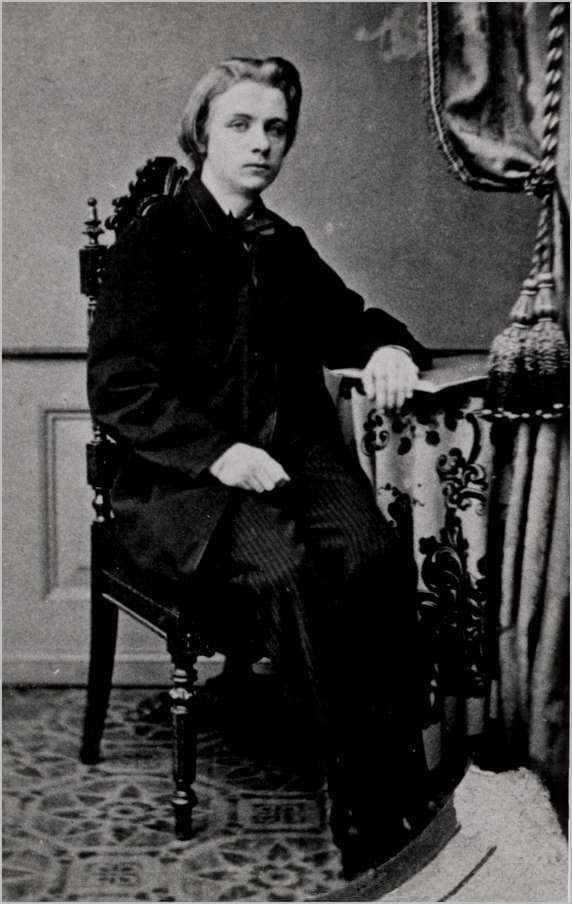

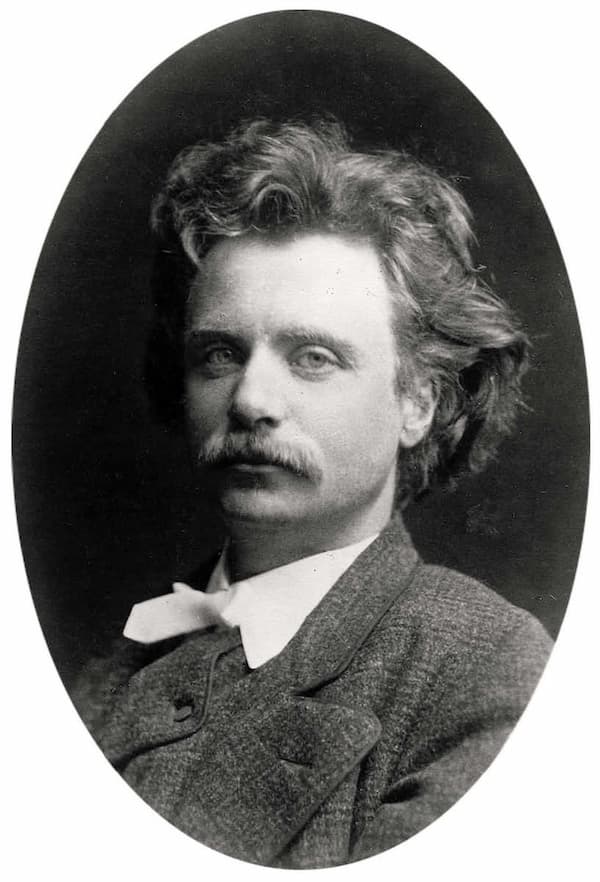

Edvard Grieg, 1858

From the foot-stomping fun of Peer Gynt to the soulful sighs of his Lyric Pieces, we have rounded up the 10 most beloved compositions that will make you yodel in a meadow or waltz with a troll.

If you are ready for a Nordic musical adventure, let’s jump straight in and explore the quirky and catchy genius of Grieg’s greatest hits!

Peer Gynt Suite

It’s only fitting that we start with one of the Peer Gynt Suites. Grieg submerges us into the wild and whimsical world of Henrik Ibsen’s play through his vibrant orchestral music. Composed in 1875, and he did write 2 different suites, Grieg captures the adventurous spirit of the roguish “Peer Gynt.”

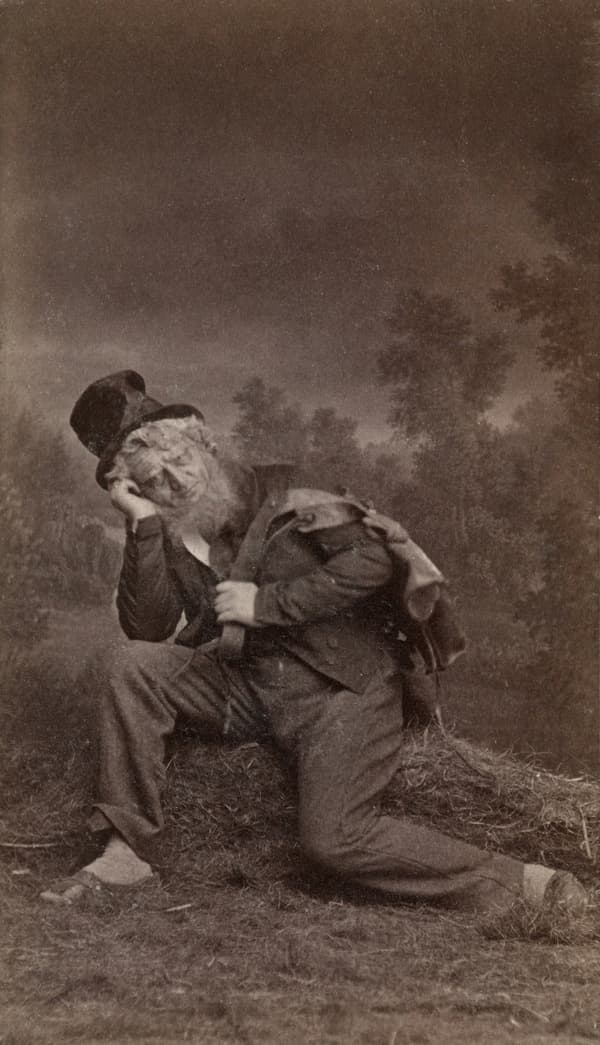

Henrik Klausen as Peer Gynt at Christiania Theater

You surely know such iconic pieces as “Morning Mood,” which paints a serene sunrise, or “In the Hall of the Mountain King,” a thrilling, mischievous romp. Infused with Norwegian folk melodies, these suites are among Grieg’s most beloved works, bursting with drama and charm.

These suites are like a musical Netflix series, each movement a new episode packed with thrills and chills. Whether you’re a classical newbie or a seasoned listener, Peer Gynt is Grieg at his storytelling best.

Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 16

Edvard Grieg cooked up his piano concerto in 1868. This piece is a wild ride, almost like a Nordic roller-coaster that starts with a thundering drumroll and the piano diving in like a Viking raid.

The first movement struts a catchy melody, and Grieg blends stormy passion with moments so tender you’ll want to hug a pine tree.

But the epic doesn’t stop there, with the second movement sounding like a cosy fireside chat, and the third with a dance so lively, you’ll swear you’re at a Scandinavian hoedown. No wonder it’s one of the most famous piano concertos ever.

Holberg Suite

The Holberg Suite is a snappy little number from 1884, that’s basically a love letter to the 18th century, but with a Norwegian twist. Grieg wrote it to celebrate the 200th birthday of Ludvig Holberg, a Danish-Norwegian writer who was like the Shakespeare of Scandinavia.

Originally written for piano, Grieg jazzed it up with strings, giving us five movements that prance around like a Baroque dance party. And the opening “Praeludium” is like a caffeinated squirrel sprinting through a fjord.

The good times keep on rolling with movements like the Sarabande, a Gavotte, and a slow Air, ending with a foot-stomping Rigaudon. Grieg was a genius by taking old-school Baroque vibes and spiking them with his Nordic charm.

Lyric Pieces

Did you know that Grieg wrote 66 short piano works that are like musical selfies of the Norwegian psyche? Each piece paints a mood, with some dreamy, some cheeky, and some vivid like a troll dodging through the forest.

These pieces are Grieg at his most playful, wrapping Nordic folklore, nature, and heart-tugging emotion into mini masterpieces. Whether you’re a beginning pianist or just an appreciative listener, the Lyric Pieces are like a box of musical chocolates.

Every single one is a sweet surprise, and trust me, you’ll want to savour them all.

Cello Sonata in A minor, Op. 36

The Grieg Cello Sonata is a masterpiece that’s like a musical bear hug between a cello and a piano. It sounds like Grieg channelled all his passion into this piece, which was actually written for his buddy, the cellist Wilhelm Sinding.

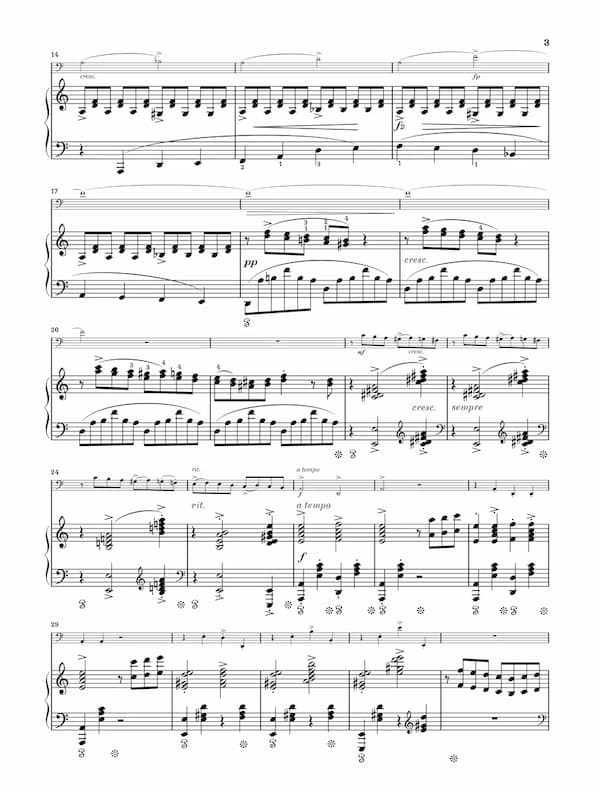

Edvard Grieg’s Cello Sonata

It’s got three movements of pure drama, starting like a Viking longship hitting choppy waters. It’s big and bold with the cello telling a saga of lost love. This is Grieg at his most cinematic, basically composing the soundtrack for a romantic comedy.

The second movement sounds like a cosy fireside chat, and the third crashes in like a Nordic festival. The cello and piano chase each other like kids playing tag in the meadow. This sonata is a rollercoaster that will make you laugh, cry, and maybe even yodel along.

String Quartet No. 1 in G minor, Op. 27

In his first string quartet, Grieg packs an entire Norwegian fjord into four string instruments. It basically sounds like a soap opera for two violins, viola, and cello. The opening movement is highly dramatic, intense, and passionate. It’s full of Grieg’s signature folk-inspired melodies, like a fiddling elf sitting on your shoulder.

Then we find a dreamy and heart-tugging waltz, with strings swaying under the northern lights and whispering sweet nothings to each other. The cheeky little intermezzo sounds like a goat going to a barn dance, and the concluding movement will leave you breathless.

This string quartet shows Grieg at his most adventurous, blending raw emotion with a folky flair, like a musical stew. It’s rich, bold, and totally unforgettable.

Violin Sonata No. 3 in C minor, Op. 45

Here comes another romantic comedy for violin and piano written by Grieg in 1887. His 3rd violin sonata is a masterpiece, a delightful Viking saga with plenty of cheeky charm. It opens with a fiery thunderstorm, the violin belting out a stormy tune and the piano tossing in sparkly chords.

If the opening movement sounds like a Nordic epic, the second will melt your heart. Grieg exchanges his Viking helmet for the beret of a poet. The violin sings a tender lullaby, and the piano sprinkles in delicate notes like fireflies on a summer night.

But don’t get too comfy as the final movement bursts in like a barn dance on caffeine. It’s a Norwegian hoedown for sure, with plenty of foot-tapping energy and a triumphant finish. It’s perfect for classical music fans or anyone ready to fall in love with a fiddle-fuelled adventure.

Haugtussa, Op. 67 (The Mountain Maid)

Grieg’s song cycle Haugtussa, based on poems by Arne Garborg, is like a musical fairy tale. It’s all about a clairvoyant shepherdess named Veslemøy, and in eight songs, Grieg is channelling his inner Nordic mystic into music.

Surrounded by goats and fjords, the dreamy farm girl imagines herself in a magical forest. However, things get juicy, as she falls in love with a hunky farm boy. Sadly, the boy is not really interested, and Veslemøy casts a musical hex.

Grieg’s genius is blending haunting Nordic vibes with catchy folk tunes, making Haugtussa feel like a campfire story told by a bard who’s had too much to drink. This cycle is a quirky emotional ride and ends with the maid finally finding solace in nature.

Ballade in G minor, Op. 24

Composed in 1874-5, the Ballade in G minor is a deeply personal set of variations on a Norwegian folk tune. Don’t be fooled, however, as this is no simple campfire ditty, with the theme rolling in all sombre and brooding.

Grieg then spins the melody into a rollercoaster of moods, from stormy tantrums to twinkly moments that feel like sunlight bouncing off a glacier. As the Ballade rolls on, Grieg flexes his compositional muscle, tossing in variations that range from angry to dreamy.

Written during a tough time in Grieg’s life, as his parents had just passed away, this piece feels like a musical diary. It feels raw and heartfelt, but in the end, it comes to a triumphant if bittersweet conclusion. It certainly is an emotional and wild ride that proves that Grieg could turn a single tune into a complete story.

Four Psalms, Op. 74

Edvard Grieg

Written for mixed choir, Grieg composed his Four Psalms in 1906; they would be his final works. Based on Norwegian hymn tunes, these serene and spiritual pieces radiate simplicity and warmth, with lush harmonies reflecting Grieg’s deep connection to his faith and heritage.

Each psalm has its own flavour and its own personal devotion. With soaring melodies, Grieg dials up the drama, with the set wrapping up with a serene glow, like a lullaby to the stars. These beautiful pieces are raw and heartfelt, blending folk roots with spiritual depth.

It’s a quiet farewell, offering a moving glimpse into the composer’s contemplative side. He captures the essence of each work while keeping the tone approachable and engaging.

Bonus Track: Norwegian Dances, Op. 35

It’s time to wrap up this little feature on the 10 most beloved compositions of Edvard Grieg by featuring his Norwegian Dances, Op. 35. Originally written for piano four-hands, they are a set of four foot-stompers that make you want to grab a partner and twirl through a fjord.

Each dance is a mini-adventure, packed with rustic charm and cheeky energy. They range from flirty waltzes at a village fair to full how-downs, like you’re galloping along like a herd of reindeer on a sugar rush. These Norwegian Dances are a rollicking romp, and you’ll want to two-step around your living room very soon.

Edvard Grieg’s ten most beloved compositions, from the whimsical charm of Peer Gynt to the heartfelt lyricism of his Lyric Pieces, continue to captivate listeners with their vibrant Norwegian spirit and timeless emotional depth. These works not only celebrate his genius but also invite us all to dance, dream, and wander through the enchanting landscapes of his musical imagination.

| |||||||

|

Ten Greatest Women Pianists of All Time

by Emily E. Hogstad, Interlude

So many women have done so that it’s impossible to make an objective list of the ten greatest women pianists of all time.

However, there’s nothing keeping music lovers from creating their own subjective lists.

Here’s one such subjective list, featuring some of the greatest women pianists who were born between 1751 and 1987.

Let us know who would be on your list!

Maria Anna Mozart (1751–1829)

Maria Anna Mozart, nicknamed Nannerl during her childhood, was Wolfgang Amadeus’s older sister.

Their father, Leopold, began teaching her keyboard when she was seven years old. She immediately proved to be a prodigy and was a full-blown virtuoso by eleven.

Maria Anna Walburga Ignatia Mozart by Pietro Antonio Lorenzoni © madamegilflurt.com

When the Mozart family first began touring Europe, Nannerl was initially the bigger draw and was often given top billing over her brother.

During her career, she played for aristocrats and royal families in Austria, Germany, France, Switzerland, and Britain.

After she turned eighteen and became of marriageable age, her family withdrew her from the concert platform. She was forced to watch from the sidelines as Wolfgang continued his travels and musical education in Italy without her.

She married a widowed magistrate in 1784 and moved to a home thirty kilometres from the family hometown of Salzburg. She had three children of her own and also helped to raise her husband’s five children from his previous marriages.

She continued to play the piano for multiple hours a day. Even after her husband died, she continued playing and teaching.

Maria Szymanowska (1789–1831)

Maria Szymanowska was born to a wealthy family in Warsaw in 1789.

We don’t know for sure how she began her musical life, but it seems likely that she studied with Frédéric Chopin’s teacher, Józef Elsner. She gave her first public recitals in 1810, the year of Chopin’s birth.

She also married in 1810 to a man named Józef Szymanowski. They would have three children together, including a set of twins. They separated in 1820.

Maria Szymanowska

Szymanowska made several tours during her marriage, but her touring activities ramped up in the 1820s. During that decade alone, she appeared in Germany, France, Britain, Holland, Belgium, Italy, and Russia.

She composed works for piano that were deeply influenced by her Polish roots. (Some historians have argued that they influenced a young Chopin.) She became a great favorite in musical salons, and many composers dedicated works to her, including Beethoven.

During her visit to St. Petersburg, she was named First Pianist to the Russian Imperial Court. In 1828, she decided to settle in St. Petersburg, but she died in the 1831 cholera epidemic, cutting short a major career.

Clara Wieck Schumann (1819–1896)

Clara Wieck was born in 1819 to piano teacher and music shop owner Friedrich Wieck. As soon as Clara was born, he decided he wanted to mold her into a great piano virtuoso.

Robert and Clara Schumann, 1850

Years of intense study followed. True to Friedrich’s prophecy, Clara proved to be one of the most talented pianists of her generation, male or female.

Her life – and classical music – was changed forever when, in the 1830s, she fell in love with her father’s student Robert Schumann.

Her father protested against the marriage for a variety of reasons, but as soon as she was legally able to, they were married in 1840.

The Schumanns had eight children together, but not even motherhood could keep Clara from continuing her performing career.

After Robert’s mental health collapsed and he died in 1856, Clara continued performing, both out of economic necessity and as a kind of therapy to guide her through her grief.

Throughout her life, she advocated for works by her husband, Chopin, Beethoven, and, perhaps most importantly, Brahms, among many others.

She also reshaped the role of the modern virtuoso, helping to popularize the modern recital format and playing from memory onstage.

Teresa Carreño (1853–1917)

Teresa Carreño was born in Caracas, Venezuela, in 1853.

When she was nine, the family emigrated to New York City, where she began her concert career in earnest. When she was ten, she played for Abraham Lincoln in the White House.

She embarked on her first European tour in 1866. She spent years there, befriending many of the giants of the art: Rossini, Gounod, and Liszt, among others.

Teresa Carreño

In 1873, she married virtuoso violinist Emile Sauret and the following year gave birth to their daughter, Emelita. Sadly, the marriage didn’t last long, and Carreño and Sauret split up.

She would go on to remarry three more times, and have four more children (one of them, Teresita, would become a concert pianist in her own right). Her turbulent love life would become part of her legend.

During the 1870s and 1880s, she spent most of her time touring America, with a couple of trips to Venezuela sprinkled in. In 1889, she returned to Europe to great success. A final large tour to America took place in the 1890s. She died in 1917 in New York City.

Conductor Henry Wood memorably wrote about her:

It is difficult to express adequately what all musicians felt about this great woman who looked like a queen among pianists – and played like a goddess. The instant she walked onto the platform her steady dignity held her audience who watched with riveted attention while she arranged the long train she habitually wore.

Dame Myra Hess (1890–1965)

Myra Hess was born in London in 1890 and began her piano studies at the age of five. She entered the Royal Academy of Music when she was twelve.

She made her orchestral debut when she was seventeen, playing the fourth Beethoven piano concerto under conductor Thomas Beecham.

Myra Hess

Her career plateaued in the late 1910s due to World War I, but she returned to touring as soon as it was over.

However, arguably her greatest artistic triumph happened during World War II, when she organized nearly seventeen hundred concerts over the course of the conflict, playing in 150.

Concert halls had to be blacked out at night to avoid bombing by Nazi planes. So Hess organized lunchtime daytime concerts at the National Gallery in London.

If bombing prevented a performance from taking place, the series would be relocated temporarily, before returning to the gallery.

Over 800,000 people attended her lunchtime concerts, making it one of the most effective morale boosters of the war.

She suffered from a stroke in 1961 and died from a heart attack in 1965.

Alicia de Larrocha (1923–2009)

Alicia de Larrocha was born in 1923 into a family of pianists in Barcelona, Spain. She began studying piano when she was three with teacher Frank Marshall, and gave her first performance when she was five. Marshall would remain her only teacher after the age of three.

She began touring internationally in her mid-twenties and enjoyed a vibrant performing career for decades thereafter.

Alicia de Larrocha

De Larrocha was especially celebrated for her advocacy of Spanish composers like Granados, de Falla, and Albéniz.

But her expertise didn’t stop there: her performances of the Germanic composers like Beethoven, Brahms, Schumann, and Mozart were also highly praised.

She even recorded Liszt, despite the fact that she was less than five feet tall and her hands were small.

She recorded extensively throughout her career and won four Grammy awards between 1975 and 1992.

She retired in 2003 after seventy-five years of public performances. She died in 2009, at the age of 86.

Martha Argerich (1941–)

Martha Argerich was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 1941, to a Spanish-Russian family. She began learning the piano at the age of three and gave her debut concert at the age of eight.

In 1955, when Martha was fourteen, the Argerich family moved to Vienna. She began studying there with iconoclast pianist Friedrich Gulda. Two years later, she won both the Geneva International Music Competition and the Ferruccio Busoni International Competition.

Martha Argerich with The Philadelphia Orchestra, 2008 © carnegiehall.org

Despite her success, she found herself in a musical crisis, and she quit playing for three years. Thankfully, she changed her mind, returning to music, and she won the International Chopin Piano Competition in 1965, when she was twenty-four. It was the kickoff to a decades-long performing career.

In the 1980s, Argerich revealed that performing solo recitals made her feel lonely, so since that time, she has focused on repertoire that includes other musicians, such as concertos and chamber music.

In addition to her storied career as a performing artist, she has worked as a teacher and mentor. She is the president of the International Piano Academy Lake Como and has appeared regularly on competition juries.

As of 2019, at the age of 78, she was still performing the Tchaikovsky piano concerto. As one critic wrote in 2016, “Her playing is still as dazzling, as frighteningly precise, as it has always been; her ability to spin gossamer threads of melody as matchless as ever.”

Mitsuko Uchida (1948–)

Mitsuko Uchida was born outside of Tokyo in 1948. Her family moved to Vienna when she was twelve, and she began studying at the Vienna Academy of Music. She made her recital debut in Vienna at fourteen.

Mitsuko Uchida © Geoffroy Schied

In 1970, when she was twenty-two, she won the second prize in the International Chopin Piano Competition. The prize marked the beginning of a decades-long career.

She has become especially renowned as an interpreter of Mozart. She has recorded all of Mozart’s piano sonatas and concertos, a staggering accomplishment.

If that wasn’t enough, she decided to re-record the Mozart concertos, while also conducting. In 2011, she won a Grammy award for the first record in the series.

She is also famous for being the artistic director at the prestigious Marlboro Music School and Festival, a position she has held since 1999. (She currently shares the position with fellow pianist Jonathan Biss.)

Even today, in her mid-seventies, she is still performing and recording.

Hélène Grimaud (1969–)

Hélène Grimaud was born in 1969 in Aix-en-Provence, France. She began playing the piano at seven.

She began studying at the Paris Conservatoire in 1982 when she was thirteen, and gave her recital debut in Tokyo five years later.

Hélène Grimaud

She gave important debuts with the Berlin Philharmonic in 1995 and New York Philharmonic in 1999.

In 2002, she signed with the prestigious Deutsche Grammophon label, and in the two decades since has released a number of well-received recordings.

She is noted for her wide interests outside of music. She is deeply involved with multiple wildlife conservation efforts and is also a member of Musicians for Human Rights.

She has also written or co-written four books. Her first, Variations sauvages (Wild Variations), published in 2003, is an autobiography. The cover features a photo of her being greeted by three wolves she has met through her wildlife conservation work.

Yuja Wang (1987–)

Yuja Wang was born to a musical family in Beijing in 1987. She began studying piano at the age of six and enrolled at the Beijing Conservatory when she was seven.

Yuja Wang, 2021

When she was fifteen, she moved to Philadelphia to study at the storied Curtis Institute of Music. She studied there with legendary pianist Gary Graffman for five years. We wrote an article about their teacher-student relationship.

She made her European debut in 2003, at the age of sixteen. Her North American debut came two years later.

Her breakthrough performance is widely considered to have happened in March 2007, when she replaced Martha Argerich at the Boston Symphony, playing Tchaikovsky’s first piano concerto.

Since then, she has been in constant demand at the best orchestras and recital venues in the world.

In 2023, she made headlines for performing all four Rachmaninoff piano concertos and his Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini. Ever a fashionista, she changed into a different dress for each concerto. She even played an encore!

In 2012, Joshua Kosman of the San Francisco Chronicle wrote that Yuja Wang is “quite simply, the most dazzlingly, uncannily gifted pianist in the concert world today, and there’s nothing left to do but sit back, listen and marvel at her artistry.”

The words were prophetic. The rich tradition of women pianists – as well as the broader tradition of pianism generally – is in good hands!

%20(1).jpg)