It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Wednesday, August 21, 2024

Haydn Symphony No. 101 'The Clock' by Adam Fischer & Danish Chamber Orchestra

Tuesday, August 20, 2024

If I Could Listen to Only 3 Classical Pieces for the Rest of My Life

Monday, August 19, 2024

Bernstein: West Side Story - 'Maria' - BBC Proms

The Sound of Music -Sierra Boggess PROMS 2010

Friday, August 16, 2024

Khatia und Gvantsa Buniaishvili: Astor Piazzolla, Libertango vierhändig

Air - Johann Sebastian Bach

The Magpie as Thief: Rossini’s La gazza ladra

by Maureen Buja

Three of Rossini’s operas mark turning points in his development as an opera composer. Semiramide, Guillaume Tell, and La gazza ladra (The Thieving Magpie) each gather up a summary of his operatic development to that point and are made into very long operas. They also share another characteristic: none of these operas show the self-borrowing that marks much of his work. Semiramide is the culmination of his opera seria work and is the turning point in his withdrawal from Italian operatic life. Guillaume Tell is the end of the series of his operas written in Naples and then Paris, which were about experimentation and exploration – this is his farewell to his career in the theatre. La gazza ladra, with its mix of serious and comic elements, is his last experiment in comic opera. His next area was the musical farce (farse), starting with L’Italiana in Algeri, where his operas called for the top soloists to take on his difficult principal roles.

Marie Françoise Constance Mayer: Gioachino Rossini (Pesaro: Casa Rossini)

La gazza ladra, which sits between opera seria and comic opera, is an opera semiseria. The opera received its premiere on 31 May 1817 at La Scala, Milan.

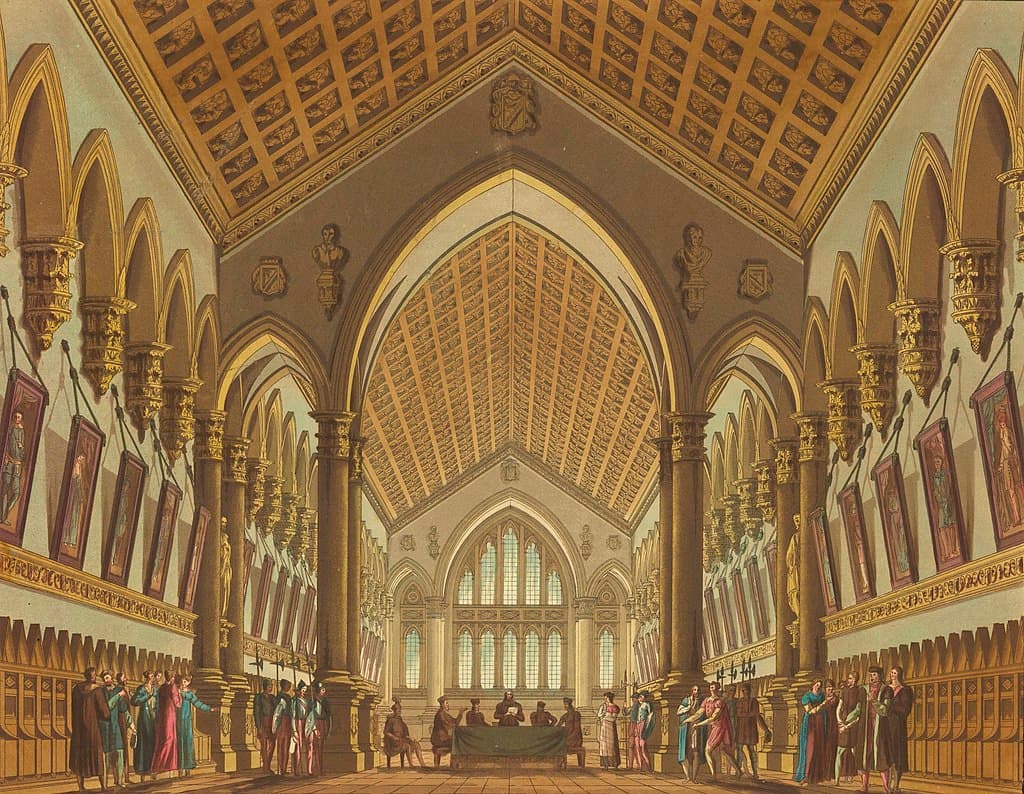

Many opera semiseria, also called melodrama, were ‘rescue operas’ which involved a class conflict between the feudal aristocracy and regular society, generally peasants. The settings are usually the village square, with the nobleman’s house (or the local prison) looming over the scene. In La gazza ladra, the climax is set in the nobleman’s court, pushing the emphasis over to a more opera seria ending.

José Álvarez Cubero: Bust of Gioachino Rossini, ca. 1819 (private owner)

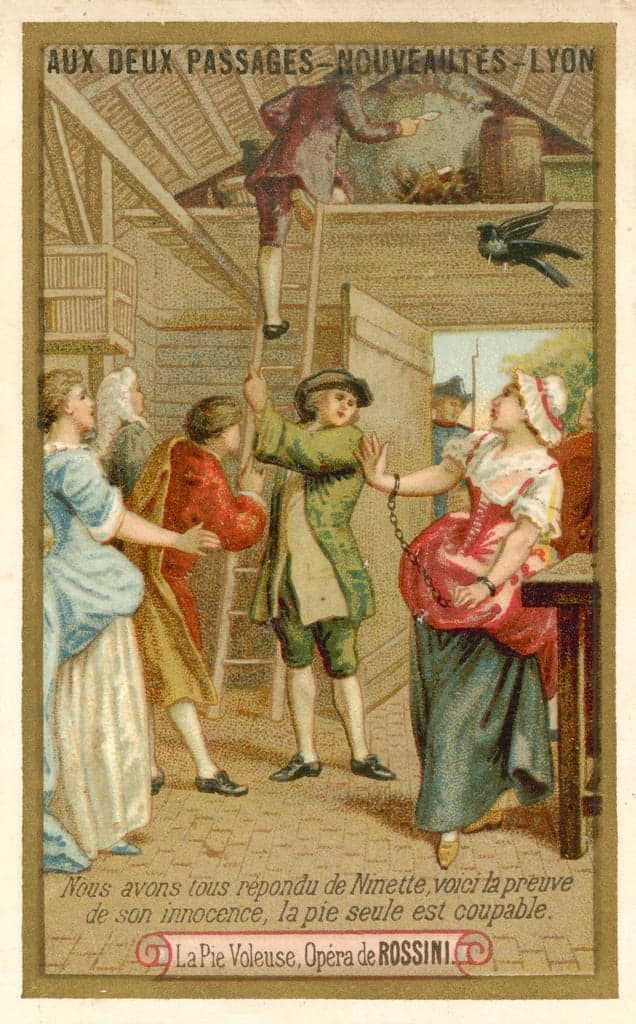

Ninetta loves Giannetto, who is on his way back from the wars. Her father, Fernando, a deserter from the army, shows up and asks her to sell two of their silver spoons so he has some money. She gathers up the spoons and is interrupted by the mayor who asks her to read out the description of a deserter in the area. She makes up a different description of her father, and while she’s doing that, a magpie swoops down and steals a spoon.

Alessandro Sanquirico: Tribunal del podestà in un grosso villaggio non molto distante da parigi : questa scena su eseguita pel melodramma La Gazza Ladra, posto in musica dal sig. Gioachimo Rossini, e rappresentato nell’J. R. Teatro alla Scala (Design for courtroom scene (Act II: 9)) (Gallica: btv1b53117267k)

Giannetto’s mother, who is not in favour of Ninetta, accuses Ninetta of theft, and as the two family spoons have the same initials on them, Ninetta is found guilty and sent to the scaffold. The magpie steals a silver coin, and when it’s followed to its nest, both Ninetta’s and Gianetta’s mother’s lost spoons are found. Will the discoverers get back to the scaffold in time to save Ninetta? Of course they do, and all have a happy ending, except the Mayor, who was hoping Giannetta’s troubles would be solved in his arms.

Discovery of the magpie’s nest

The overture, which starts with a snappy drum roll, is significant for its use of snare drums.

Gioachino Rossini: La gazza ladra Overture

This 1928 recording was conducted by Ernst Viebig, leading the Berlin State Opera Orchestra. Ernst Viebig (1897–1959) was an accomplished composer from a family with literary connections. His father was a publisher and his mother a writer. His original name was a hyphenated version of his parents’ names, Cohn-Viebig, and was shortened to Viebig in 1914 when he wanted to join the army. The family hoped that eliminating his father’s Jewish name would make his way easier. His father had converted to Lutheran Protestantism when he married Clara Viebig.

Ernst Viebig

Family connections brought the world of literature to the house and his own interests in music started with the piano, with a particular skill in improvisation. He served in WWI and returned to Berlin with a position at the Electrola record company as musical director, while also serving as a bandmaster and composer. With the rise of the National Socialists in Germany and an inquiry by the Gestapo about his Jewish background, he decided to leave Germany for South America. His music did not find favour there and he and his second wife opened a German bookstore in Rio de Janeiro and then in São Paulo. He returned to Berlin in 1958 but could not find work and retired to Lower Bavaria where he died in 1959.

As the musical director at Electrola in the 1920s, he played an important role in their recordings. As a conductor, he made not only this La gazza ladra recording but also important recordings of the overture to von Suppé’s operetta The Beautiful Galathée and Puccini’s Turandot Fantasy.

Performed by

Ernst Viebig

Berlin State Opera Orchestra

Recorded in 1928

Official Website

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

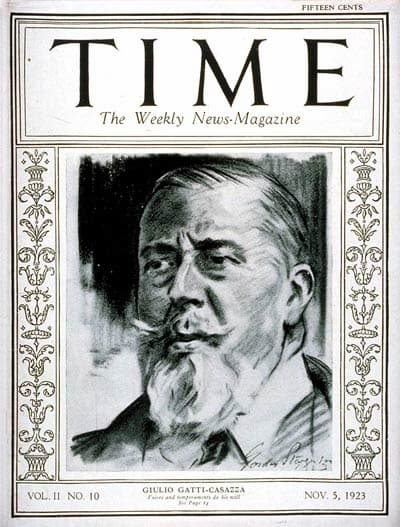

Movers and Shakers: Giulio Gatti-Casazza (1869-1940)

by Georg Predota

He single-handedly revolutionized the world of opera by applying an unprecedented entrepreneurial philosophy to arts management. Giulio Gatti-Casazza managed La Scala in Milan for a decade, and he also served as the general manager of the Metropolitan Opera of New York for a record 27 seasons! His ideas of organizing opera houses as not-for-profit cultural companies situated an ancient art form decidedly in the modern world.

Giulio Gatti-Casazza

“Even the greatest genius,” he writes, “would not be able to change the nature of things and prevent the theater from being a great public service; its two faces, artistic and economic, must be wisely harmonized, to ensure the survival of an organism that is so schematic, but not less alive.” Gatti-Casazza was born in Udine but spent his formative years in Ferrara. He studied naval engineering, but his love of opera compelled him to take on the role of general manager at the Teatro Comunale in Ferrara. His way of combining knowledge of opera, his love for music and his gift for management soon attracted attention elsewhere.

Giacomo Puccini: Madama Butterfly, “Love Duet”

At the recommendation of Arrigo Boito, Gatti-Casazza became the general manager of La Scala, and he oversaw the premiere of Puccini’s Madama Butterfly. And as you might know, he brought with him a 29-year old gifted conductor from Parma by the name of Arturo Toscanini!

Arturo Toscanini

He approached his appointment with an almost maniacal passion for organization. Guided by instinct, curiosity and a clear project vision, he made radical changes in Milan. He turned the opera house into a not-for-profit institution dedicated entirely to lyric art. In addition, his vision and unshakable faith in the power of Art meant that the repertoire at La Scala was no longer confined to native composers but reflected wider European operatic expressions. His approach quickly raised eyebrows in Paris and Vienna, and came to the attention of Otto Kahn, chairman of the Met board. He strongly believed that the company needed a robust and creative leader for the future.

Giacomo Puccini: Il Trittico, “Gianni Schicci-O mio babino caro”

Gatti-Casazza arrived in New York in 1908 and brought Toscanini with him. Toscanini became the guiding artistic presence—at least until 1915—and Gatti-Casazza engaged the most important singers of the day, starting with the young Enrico Caruso and Geraldine Farrar. He brought Puccini to New York to oversee a production of Madama Butterfly as well as commissioning La Fanciulla del West and Il Trittico. Listening to Verdi’s advice, Gatti-Casazza made it his vision to have a full house every night, and Toscanini made it a priority to elevate the Met orchestra and chorus into great virtuoso artists. But what is more, Gatti-Casazza was eager to adopt new technologies and made audio recordings of the Met’s leading singers. He also initiated live radio broadcasts of opera from the Met stage, creating the template that still informs the Met transmissions on satellite radio and HD broadcasts in cinemas worldwide.

Engelbert Humperdinck: Hansel and Gretel, “The Witch’s Ride”

In a number of short years, Gatti-Casazza had turned opera into a cultural product in the corporate sense. High-quality productions combined with a self-sufficient business model raise funds without a single dollar of public subsidy. His brilliant insights into the needs of the business helped him to overcome a number of severe predicaments. Toscanini resigned and returned to Italy in 1915, and WWI prevented many European singers from coming to New York.

Giacomo Puccini with Giulio Gatti-Casazza, David Belasco

and Arturo Toscanini in New York

Responding to that need, Gatti-Casazza spearheaded the development of American talent. Under Gatti-Casazza’s leadership, the Met even survived the stock market crash of 1929 and the prolonged depression. He looked at every crisis not as a danger but as an opportunity. Although he never fully mastered the English language, he insisted that operas be done in their original languages if possible. Gatti-Casazza left New York in 1935, but only after having introduced his last great discovery, the soprano Kirsten Flagstad.

Five Conductors Who Died on the Podium

by Emily E. Hogstad, Interlude

So it’s no surprise that over the course of music history, quite a few conductors have died or suffered fatal injuries while on the podium.

Today, we’re looking at the stories of five conductors who did what they loved until the very end of their lives – and what music they were conducting when they passed away.

Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632-1687)

Portrait of Jean-Baptiste Lully by Paul Mignard

Lully was born in Tuscany in 1632. Historians don’t know a lot about his childhood, but it appears that he studied both music and dancing.

When he was in his early teens, he was plucked off the street by a chevalier who was searching for an Italian conversation partner for his niece, Anne Marie Louise d’Orléans, Duchess of Montpensier, who was heiress to one of the greatest fortunes in Europe.

This was his introduction to the French aristocracy. In 1653, he made a big impression while dancing with Louis XIV, the future Sun King. Within weeks, he was named royal composer for instrumental music.

In 1661, Lully was named superintendent of the royal music and music master of the royal family.

He fell into disfavor in the 1680s as rumors swirled surrounding his same-sex relationships. In 1685, he was accused of having an inappropriate relationship with a pageboy, and his home was raided by police. Although he never faced any legal consequences, the social and professional costs were steep, and Louis XIV distanced himself.

In 1687, Louis XIV underwent dental surgery. Things went sideways during the procedure, but somehow he survived. To celebrate the monarch’s unlikely recovery, Lully wrote a Te Deum.

During the performance, he used a staff to keep time and accidentally hit his foot with it. Gangrene set in, and Lully refused an amputation because didn’t want to give up his ability to dance. He died on 22 March 1687.

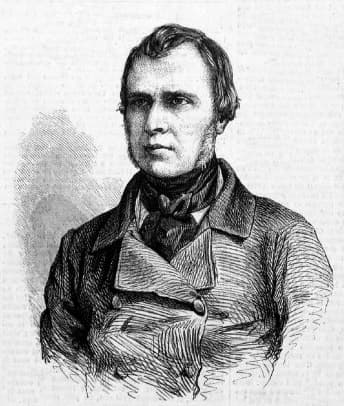

Narcisse Girard (1797-1860)

Narcisse Girard

Narcisse Girard was born in Nantes, France, and studied at the Paris Conservatoire with violinist Pierre Baillot and Beethoven‘s friend Anton Reicha.

As a young man, he scored prestigious positions at the Opéra Italien, Opéra Comique, and Paris Opéra in Paris.

He gave a series of important premieres, including Hector Berlioz’s work for viola and orchestra Harold en Italie in 1834; Giacomo Meyerbeer’s opera Le prophète in 1849; and Charles Gounod’s opera Sapho in 1851.

One of his career highlights was conducting a performance of the Mozart Requiem at Chopin’s memorial service.

In 1860, he fell ill and conducted a concert at the Conservatoire while sick. Next he took on a performance of Meyerbeer’s opera Les Huguenots, which clocks in at close to four hours. After the third act, Girard collapsed and later died.

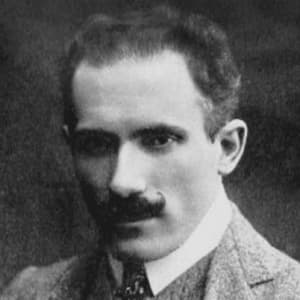

Dimitri Mitropoulos (1896-1960)

Dimitri Mitropoulos

Dimitri Mitropoulos was born in Athens in 1896. He studied at the Athens Conservatory before becoming an assistant conductor at the Berlin State Opera.

One memorable performance in Berlin in 1930 saw him play and conduct Prokofiev’s third piano concerto from the keyboard after the scheduled soloist had fallen ill.

He emigrated to the United States in 1936 and conducted orchestras in Boston and Minneapolis before becoming the music director of the New York Philharmonic in 1951.

His young, dynamic student Leonard Bernstein succeeded him in 1957. Mitropoulos’s gentle persona, inability to enforce strict discipline with his players, bad press, and rumored homosexuality all combined to end his music directorship at the Philharmonic.

He spent the rest of his career specializing in opera. He gave many performances at the Metropolitan Opera.

In November 1960, Mitropoulos was rehearsing Mahler’s massive third symphony at La Scala Opera House in Milan. According to press reports, he stopped, mumbled that he was feeling sick, and collapsed. The musicians immediately stopped playing and tried to assist him, but it was no use; he had suffered a massive cerebral haemorrhage. He died on his way to a Milanese hospital.

Eduard van Beinum (1900-1959)

Eduard van Beinum

Eduard van Beinum was born in 1900 in the city of Arnhem in the Netherlands. He studied violin, viola, and piano as a child, and when he was eighteen, joined the Arnhem Orchestra. Later he attended the Amsterdam Conservatory.

In 1929, he conducted the Concertgebouw Orchestra for the first time. Two years later, he was named second conductor, under the esteemed – and autocratic – Willem Mengelberg.

During the Nazi invasion, the two men found themselves caught up in politics.

Mengelberg flirted with Nazism, being photographed with Nazi officials and once telling an interviewer he drank champagne when the Netherlands surrendered to Nazi forces. His words and actions eventually forced him into postwar exile in Switzerland.

Meanwhile, the genial van Beinum refused to conduct a Nazi benefit concert in 1943 and threatened to resign from his position if he was compelled to play the event.

Eduard van Beinum Conducts Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3 Op.55

After Mengelberg was pushed out in 1945, van Beinum stepped up to become the ensemble’s music director. He also served at various times as music director of the London Philharmonic and the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

On 13 April 1959, van Beinum was at the Concertgebouw rehearsing Brahms’s first symphony when he had a heart attack and died.

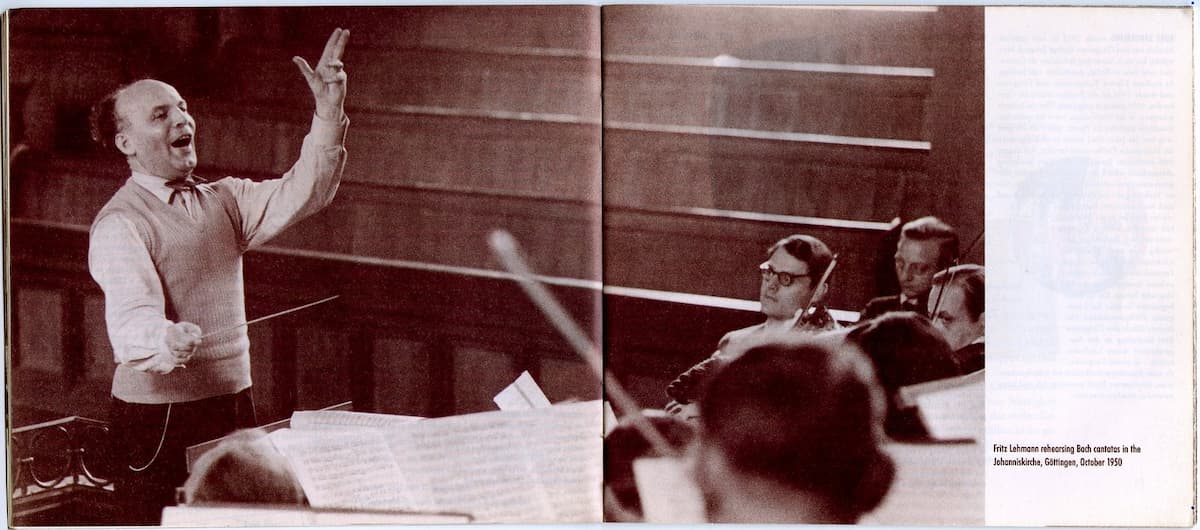

Fritz Lehmann (1904-1956)

Fritz Lehmann

Fritz Lehmann was born into a musical family in Mannheim, Germany, in 1904. As a teenager, he studied at the Hochschule für Musik in Mannheim, eventually transferring to universities in Heidelberg and Göttingen.

He made a career conducting various German orchestras, and in 1934, he was hired as the conductor of the Göttingen International Handel Festival. Ten years later, he resigned when, like van Beinum, he came in conflict with Nazi officials.

One of his specialties was Johann Sebastian Bach. On Good Friday in 1956, he conducted a particularly fateful performance of the St. Matthew Passion in Munich.

During the performance, he had a heart attack and collapsed. A replacement conductor came out to finish the work. After the Passion was finished, it was announced that Lehmann had not survived.