by Georg Predota

Louis-Nicolas Clérambault: Orphée

Blending Elegance and Innovation

French composers adapted the form to suit national tastes, emphasising clarity of text, elegant melodic lines, and a more restrained emotional palette compared to the dramatic intensity of their Italian counterparts. Typically written for solo voice with continuo and sometimes additional instruments like violins or flutes, French cantatas were often performed in intimate settings, such as salons or private concerts, reflecting the cultural emphasis on refinement and intellectual discourse.

Composers like Louis-Nicolas Clérambault, André Campra, and Élisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre crafted cantatas that drew on mythological, pastoral, or moral themes, aligning with the French preference for narrative clarity and poetic sophistication. The development of the French cantata was also tied to the cultural politics of the time, as “composers navigated the tension between Italian musical innovation and the conservative preferences of the French court under Louis XIV,” which favoured the tragédie en musique of Jean-Baptiste Lully.

By the mid-18th century, the French cantata began to wane in popularity as musical tastes shifted toward larger-scale operatic works and the emerging galant style, which prioritised simplicity and accessibility over the intricate counterpoint and formal complexity of the Baroque cantata. Nevertheless, the genre remained a significant vehicle for compositional experimentation, particularly in its integration of French lyricism with Italian virtuosity.

Clérambault: Orphée

Louis-Nicolas Clérambault

Louis-Nicolas Clérambault (1676–1749) was born into a musical family in Paris, and he served as organist at the prestigious Saint-Sulpice and held posts at the French court. Primarily celebrated for his contributions to the French cantata and sacred music, Clérambault infused Italianate virtuosity with the elegant clarity of the French style. In all, he composed a total of 25 French cantatas that stand as the pinnacle of his compositional output.

His works, often set to mythological or pastoral texts, reflect the refined tastes of the Parisian salons where they were performed. The Orpheus myth, with its themes of love, loss, and the transformative power of music, provided Clérambault with a compelling narrative canvas. In Orphée, Clérambault sets a French text that traces Orpheus’s descent into the underworld to retrieve Eurydice, his beloved, emphasising his anguish and fleeting hope through poignant airs and dramatic recitatives.

The cantata’s structure alternates between recitative, which advances the narrative, and lyrical airs, which delve into emotional reflection. A striking feature is the “Air tendre” where Orpheus pleads with Pluto, marked by a lilting, almost hypnotic melody that mirrors Orpheus’s legendary musical charm. Clérambault’s use of chromatic harmonies and suspensions heightens the sense of longing, while his instrumental writing echoes the vocal line, creating a dialogue that feels intimate yet expressive.

The cantata also subtly engages with contemporary cultural currents, as Orpheus symbolised the artist’s divine gift, a theme resonant with the French court’s self-image as a patron of the arts under Louis XIV and beyond. The work reflects the French Baroque’s fascination with emotional depth, rhetorical clarity, and refined artistry. Clérambault’s Orphée stands out for its emotional directness and compact form, making it ideal for the salon setting where aristocratic patrons valued subtlety over spectacle.

Campra: Arion

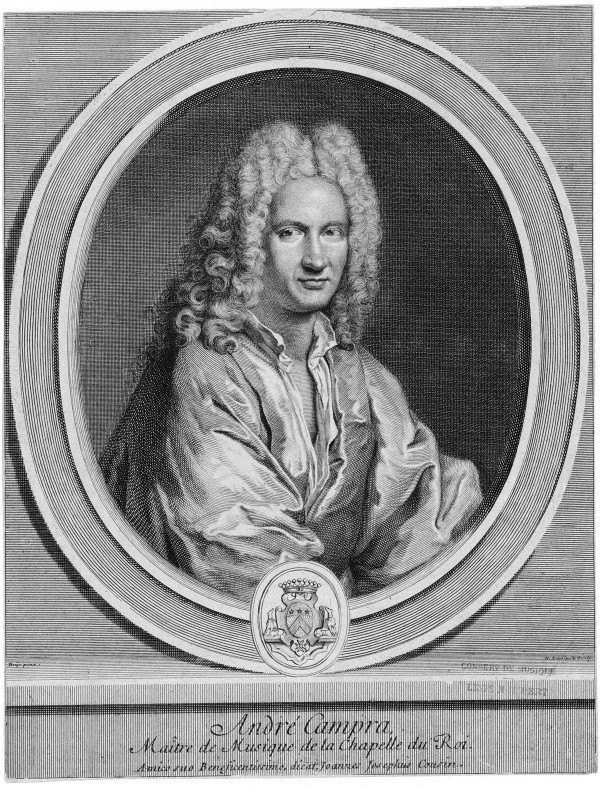

André Campra

André Campra (1660–1744) was born in Aix-en-Provence and initially pursued a career in the church, serving as maître de musique at Notre-Dame in Paris. He gained fame for his opera but also applied his skill to the cantata genre by merging national traditions. As he writes in 1708, “As cantatas have become fashionable, I thought I should, at the request of many people, provide some for the public in my own way.”

“I have tried, as far as I could, to combine the delicacy of French music with the liveliness of Italian music: perhaps those who have completely abandoned the taste for the former will be satisfied by the way in which I have treated this little piece. I am as convinced as anyone of the merits of the Italians, but our language cannot tolerate certain things that they get away with. Our music has beauties which they cannot help admiring and try to imitate. I have endeavoured above all to preserve the beauty of the singing, the expression, and our way of reciting.”

Arion is a secular French cantata from his Cantates françoises of 1714, and it draws its story from the classical tale of Arion, a legendary Greek musician. In the story, Arion’s lyrical prowess saves him when sailors attempt to murder him for his wealth, as dolphins, enchanted by his song, carry him to safety.

Campra’s setting of this myth uses the narrative to showcase the power of music, a theme that resonated deeply with the aristocratic audiences of early eighteenth-century France. Structurally, Arion follows the typical French cantata form, with alternating recitatives and airs accompanied by a small ensemble. The opening prelude establishes a pastoral tone, while the recitatives narrate Arion’s plight with dramatic shifts in tempo and dynamics. The airs, particularly those depicting Arion’s song to the dolphins, feature ornate vocal lines with agréments, reflecting the French emphasis on expressive nuance.

de Montéclair: Pan et Syrinx

Michel Pignolet de Montéclair

The French Baroque composer and theorist Michel Pignolet de Montéclair (1667–1737) was known for his contributions to opera, cantatas, and music pedagogy. Born in Andelot, he moved to Paris, where he joined the orchestra of the Paris Opéra and later became a respected teacher. A versatile musician, he also authored influential treatises on music theory and performance, and his compositions bridged the refined tastes of the French court with the innovative trends of the early 18th century, leaving a lasting impact on the Baroque repertoire.

The cantata Pan et Syrinx draws on Ovid’s Metamorphoses, which recounts how Pan, enamoured with the chaste nymph Syrinx, chases her until she transforms into reeds to escape him, from which Pan crafts his iconic panpipes. This tale of desire, transformation, and the origins of music provided Montéclair with a rich narrative for a cantata performed with a small ensemble in salon settings.

Alternating between recitatives that narrate the story and airs that explore the characters’ emotions, Montéclair’s music vividly captures the drama. The sprightly, dance-like melodies in the opening prelude evoke Pan’s playful pursuit, contrasted by lyrical, flowing airs for Syrinx’s pleas for freedom.

His use of text painting is particularly striking, such as in passages where the flute mimics the sound of Pan’s reeds or where chromatic harmonies underscore Syrinx’s fear. The structure reflects the French Baroque’s emphasis on clarity and emotional directness, while Montéclair’s inclusion of pastoral elements, like the lilting rhythms and flute obligatos, ties the work to the era’s fascination with idyllic nature.

Dornel: Le Tombeau de Clorinde

Cover page Louis-Antoine Dornel’s Le Tombeau de Clorinde

Louis-Antoine Dornel (c. 1680–1765) was a composer, harpsichordist, organist, and violinist, active in Paris during the early 18th century. Likely born in Béthemont-la-Forêt or Presles, he served as organist at Sainte Madeleine-en-la-Cité, a position he secured over Jean-Philippe Rameau, and later as maître de musique at the Académie Française. Dornel’s compositions include chamber music, harpsichord suites, and a number of cantatas that contributed to the vibrant cultural exchange of the French Baroque.

Le Tombeau de Clorinde dates from 1723 and draws on the tragic story of Clorinde, a character from Torquato Tasso’s epic Jerusalem Delivered. It tells the story of Clorinde, a Saracen warrior-princess, who is tragically killed in combat by her Christian lover Tancred, who was unaware of her identity.

This narrative of doomed love and mourning provided Dornel with a dramatic framework. Typically performed by a solo voice, most often a baritone with a small ensemble including violin and continue, Le Tombeau alternates between recitatives and airs to convey the story’s emotional arc.

The opening recitative, “Dans l’horreur d’un combat,” sets a sombre tone, depicting the horror of battle, while subsequent airs, such as “Ô vous, Manes sacrées,” express Tancred’s grief with lyrical depth and ornamented vocal lines. Dornel’s music employs a good amount of text painting, with descending melodic figures and chromatic harmonies evoking sorrow, and the violin’s obbligato lines intertwine with the voice to heighten the lament’s intimacy.

de La Guerre: Judith

Élisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre

Élisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre (1665–1729) was a French Baroque composer, harpsichordist, and singer, celebrated as one of the most gifted musicians of her time. Born into a musical family in Paris, she performed as a child prodigy at the court of Louis XIV, earning royal patronage. Trained by her father, she excelled in composing across genres, and while her output consists largely of harpsichord music, she was the first woman to have an opera performed at the Académie royale de musique (the Opéra) in Paris. She was also the first composer in France to publish sacred cantatas, including Judith of 1708.

The cantata is rooted in the Book of Judith, recounting Judith’s heroic act of seduction and assassination of the Assyrian general Holofernes to save her people. The music for Judith emphasises spiritual depth, aligning with the period’s growing interest in sacred music for private settings during the Regency of Louis XV. The cantata’s structure, with its compact yet expressive form, highlights Jacquet de La Guerre’s innovative approach to text setting, using subtle dynamic shifts and harmonic progressions to convey Judith’s transformation from supplicant to victor.

Her instrumental writing, particularly for the violin, anticipates the more integrated textures of later Baroque music. The opening recitative sets the scene with vivid imagery of the Assyrian threat, using declamatory vocal lines to evoke urgency. The subsequent airs, such as those depicting Judith’s prayer of triumph, feature lyrical melodies adorned with French ornaments. Her use of text painting is notable, with rising melodic lines for Judith’s resolve and darker, chromatic harmonies for Holofernes’s menace.

The work also holds cultural significance as a product of a female composer navigating a male-dominated field, with Jacquet de La Guerre’s dedication of her cantatas to the Elector of Bavaria reflecting her ambition to gain recognition beyond France. Judith thus stands as a testament to her compositional skill and the French cantata’s role as a vehicle for both artistic and moral expression in the early eighteenth century.

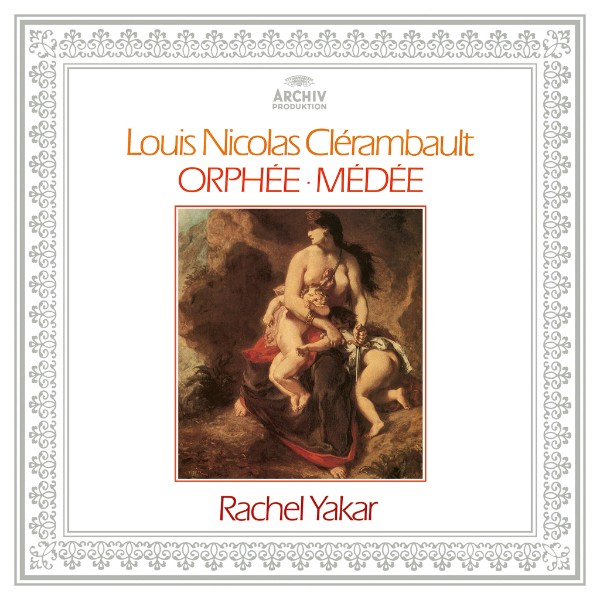

Clérambault: Medée

Louis-Nicolas Clérambault’s Médée, a secular French cantata from his Cantates françoises of 1713, showcases his mastery of dramatic vocal music and emotional intensity. Drawing on the mythological tragedy of Medea, the sorceress who exacts vengeance on her unfaithful lover Jason, this cantata captures the raw passion and turmoil of its protagonist in a form designed for intimate salon performances.

This tale of love, betrayal, and vengeance provided Clérambault with a dramatic narrative ideally suited to the French cantata’s expressive capabilities. Performed typically by a solo soprano with a small ensemble of violin, flute, and continuo, Médée alternates between recitatives and airs to convey the protagonist’s emotional descent.

The opening recitative, “Ingrate, tu trahis,” sets a tempestuous tone, with declamatory vocal lines and shifting harmonies that mirror Medea’s rage. The airs, such as “Dieux cruels, dieux vengeurs,” feature florid melodies and French ornaments, which emphasise her anguish and resolve. Jagged melodic contours and chromatic dissonances evoke Medea’s tormented psyche, while the instrumental parts amplify the drama.

The text, crafted with elegant prosody, allows Clérambault to balance rhetorical clarity with intense emotion, creating a vivid portrait of a woman consumed by betrayal. Performed in the refined setting of Parisian salons, Médée appealed to aristocratic audiences who valued the French Baroque’s blend of mythological storytelling and musical sophistication, reflecting the era’s fascination with strong and complex female figures.

Closing Thoughts

The French cantata was a major poetic and musical genre of the 18th century. Born in the 17th century and originally imported from Italy, it took many different forms in France. Initially it was simply transplanted in its original language and form but soon translated and developed to accompany the French poetic style, undergoing a dialectic change.

The decline of the French cantata by the 1740s coincided with the rise of public concerts, such as the Concert Spirituel, “which favoured orchestral and sacred music over chamber genres.” Scholarly analysis has highlighted the French cantata’s role as a cultural artefact, reflecting the tensions between tradition and innovation in French music, as well as the social dynamics of patronage and performance in the aristocratic salons of the period. Its legacy endures in the way it shaped the development of French vocal music, influencing later genres like the opéra-comique and the mélodie.