It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Sunday, March 12, 2023

Matt Monro - Portrait Of My Love / Walk Away / Born Free

Khatia Buniatishvili - Rachmaninov: Variation 18 from "Rhapsody on a Theme

Dorina Santers - Goodbye My Love Goodbye (Full Video HD)

Concierto de Aranjuez - Joaquín Rodrigo | SSO | Bokyung Byun, guitar

Nicknamed Compositions by Johann Sebastian Bach

By Hermione Lai

3D portrait of J.S. Bach by Hadi Karimi

For most of his life, Bach was insanely busy with work. But let’s not forget that during his two marriages, he sired twenty children and that his son Carl Philipp Emanuel called his father’s household in Leipzig a “pigeon coop.” An eminent musician and scholar writes, “Bach had normal flaws and failings, which makes him very approachable. But he had this unfathomably brilliant mind and a capacity to hear music and then to deliver music that is beyond the capacity of pretty well any musician before or since.” I suppose this means that Bach was a highly practical and well-organized individual and that he did not really take the time to give nicknames to the majority of his more than 1,000 compositions. Scholars, critics, or the circumstances of composition, as we have already seen with Haydn, Mozart, Schubert, and Beethoven supplied many of these nicknames. Let’s get started with some nicknamed compositions by Johann Sebastian Bach.

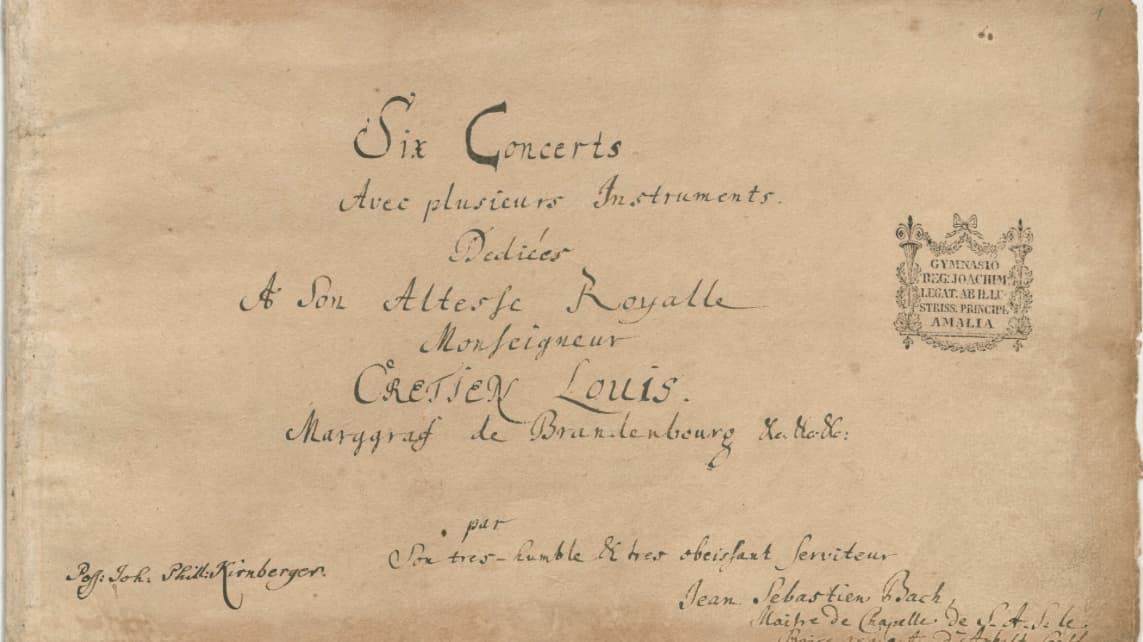

The collection of six concertos for several instruments, better known as the “Brandenburg Concertos,” are some of the best orchestral compositions by Bach. In fact, they are arguably some of the best orchestral compositions of the entire Baroque era. That particular nickname does not come from Bach, but from the circumstance surrounding their composition. Bach was employed by Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen in 1719, and the Prince sent Bach to Berlin to try out and negotiate for a new harpsichord for the court.

Title page of J.S. Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto

Once he had arrived, Bach informally played on a couple of instruments in the presence of Christian Ludwig, the Margrave of Brandenburg-Schwedt. Bach probably played some of his famous improvisations, and he was invited to send some compositions to the Margrave. Bach really did not take this commission seriously until two years later, when Prince Leopold sacked him for insubordination. Now that he had to look for employment elsewhere, he remembered the commission and he sent the Margrave six instrumental compositions. According to the composer “they were written to exploit the resources of Cöthen.” However, these resources did not seem to have been available to the Margrave of Brandenburg. As such, Bach received no thanks, no fees, and no employment offer.

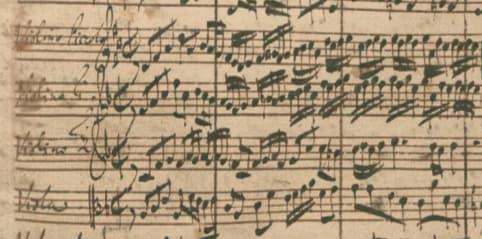

Manuscript of Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto

The autograph manuscript of the “Brandenburg Concertos” stayed in the Margrave’s library until his death in 1734, and it was then sold to the archives of the city of Brandenburg for the equivalent of 20 US dollars. Rediscovered only in 1849, the “Brandenburg Concertos” were first published in 1850. And we are very lucky to still have the autograph manuscript, as it was nearly destroyed by aerial bombardment during World War II. The unlikely hero turns out to have been a librarian, who hid the scores under his coat.

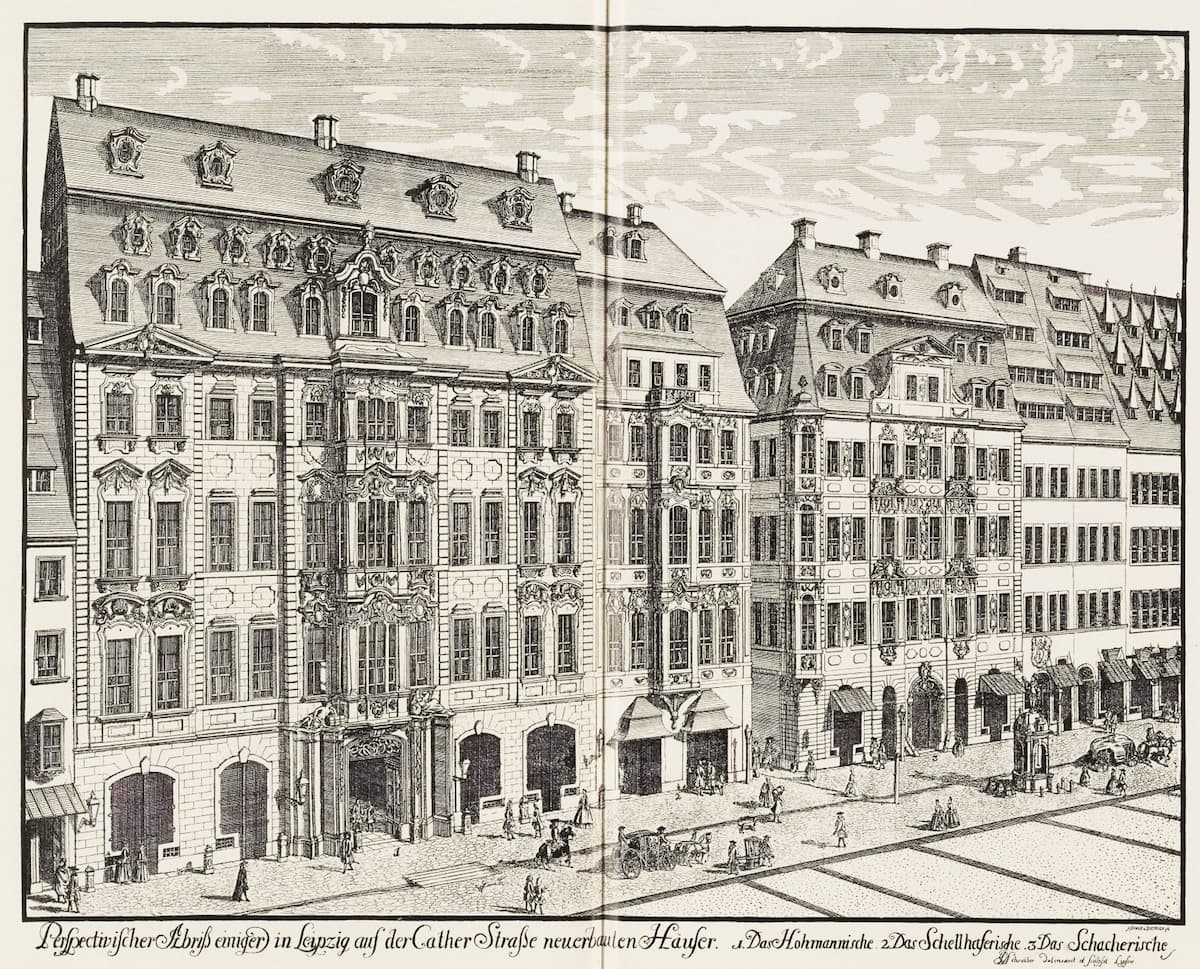

In 1715, Gottfried Zimmermann opened his famous café in Leipzig. Located in the most elegant street of Leipzig, Zimmermann began to host Friday evening concerts to attract customers. The Collegium Musicum founded by Georg Philipp Telemann started performances there in 1720, and by the time Johann Sebastian Bach moved to Leipzig in 1723, it had become a chic meeting place for the middle classes and gentlemen. “While single women were forbidden from frequenting the café, they could attend the public concerts.” Bach took over the “Collegium” concerts between 1729 and 1739, and the concerts held at the Zimmermann café lasted about two hours. The music consisted of German and Italian opera, chamber music, works for orchestra, and secular cantatas. Experts are unsure if Bach’s Schweigt stille, plaudert nicht (Be still, stop chatting,) BWV 211 was actually performed at this venue, but it certainly became highly popular under the nickname “Coffee Cantata.” It dates from 1735 and is a delicious mini-opera centered on a comic dispute between a father and his daughter and her coffee-drinking addiction. The heroine Aria just loves coffee, and she complains bitterly:

Café Zimmermann in Leipzig, 1720

Father sir, but do not be so harsh!

If I couldn’t, three times a day,

be allowed to drink my little cup of coffee,

in my anguish I will turn into

a shriveled-up roast goat.

Ah! How sweet coffee tastes,

more delicious than a thousand kisses,

milder than muscatel wine.

Coffee, I have to have coffee,

and, if someone wants to pamper me,

ah, then bring me coffee as a gift!

Father and daughter eventually reconcile, and the nickname “Coffee Cantata” might easily have originated during Bach’s day. As we can see, Bach wasn’t a mere workaholic; he also knew how to have fun.

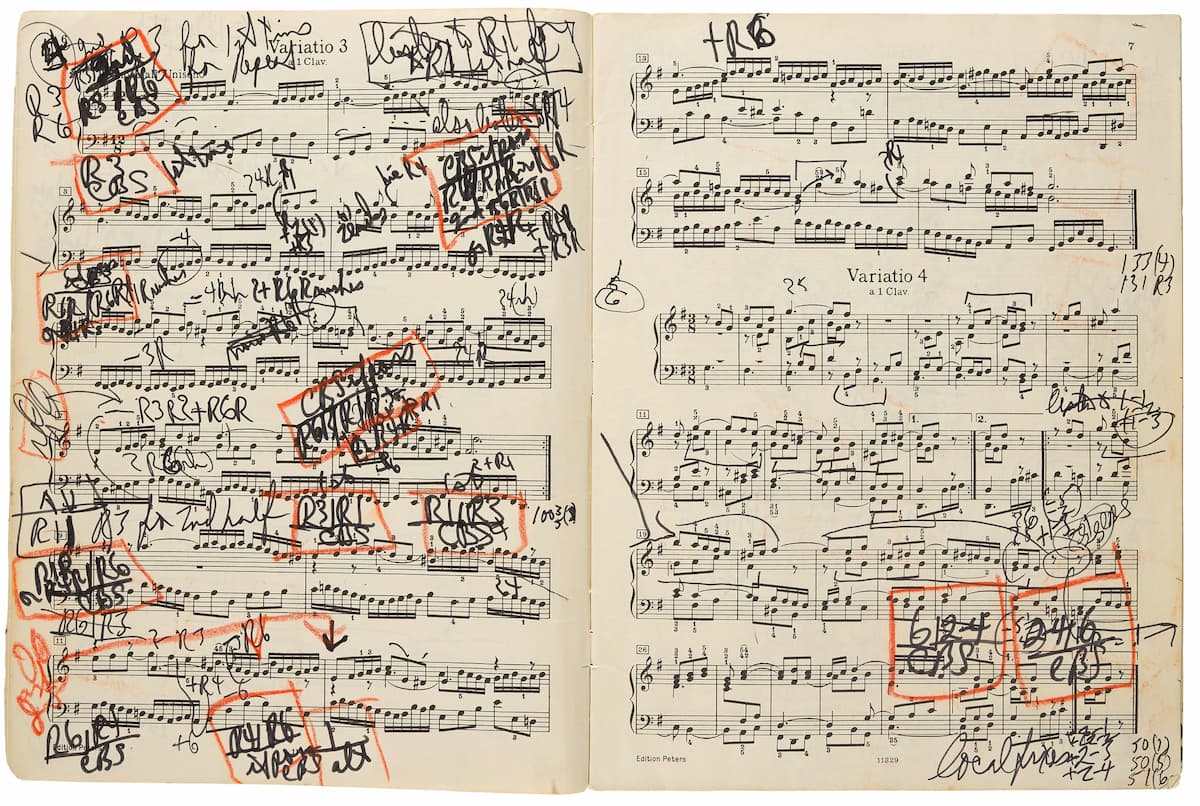

In 1741, Johann Sebastian Bach published the 4th part of his “Keyboard Exercises” under the title “Clavier Übung bestehend in einer Aria mit verschiedenen Verænderungen vors Clavicimbal mit 2 Manualen.” Translated this simply means “Keyboard Exercise, consisting of an Aria with diverse variations for harpsichord with two manuals.” The first edition published by Balthasar Schmid in Nuremberg further states that it “was composed for connoisseurs, for the refreshment of their spirits.” Today every music lover knows this set simply under the name “Goldberg Variations.” Bach composed the work on commission from Herman Karl von Keyserlingk, the Russian ambassador to Saxony. Count Keyserlingk suffered from extended bouts of insomnia, and to ease his torment during the dark and long hours of the night, he instructed his private harpsichordist Johann Gottlieb Goldberg to play for him in the antechamber. Apparently, the Count once mentioned in Bach’s presence that he would like to have some clavier pieces for Goldberg. Goldberg was an exceptionally talented keyboard performer, and musicians marveled at his ability suggesting, “never there was anybody who was a stronger player.” While Goldberg was a phenomenal performer, the Bach biographer Nicolaus Forkel tells us that “he had no special talent for composition.”

Glenn Gould’s markings on Bach’s Goldberg Variations

Since Count Keyserlingk was looking for pieces “which should be of such smooth and somewhat lively character that he might be a little cheered up by them in his sleepless nights,” Bach went to work and composed the variation set. He officially presented a copy of the first edition to Count Keyserlingk, and was rewarded with a golden goblet filled with 100 gold “Louis d’or,” a veritable fortune. Among the most sophisticated works ever written for keyboard, the Goldberg Variations are sublime and compassionate, graceful, warm, and relentlessly intricate. Nobody would dare to call them “Keyboard Exercises” today.

In his day, Johann Sebastian Bach was primarily known as a keyboard virtuoso. At the age of 23, he was appointed court musician in the chapel of Duke Johann Ernst in Weimar. He would only stay for seven months, but his reputation as a keyboard genius had already reached the town of Arnstadt, and he was quickly invited to inspect the new organ, and he gave the inaugural recital at Saint Boniface. His appointment as organist soon followed, but he was dissatisfied with the standards of the singers in the choir. So, when he was offered the position of organist at Saint Blasius in Mühlhausen, he quickly took up the invitation. His reputation as a performer continued to grow, and in 1708 he returned to Weimar as organist and concertmaster at the ducal court. Surrounded by professional musicians, Bach began to compose keyboard and orchestral works, including the preludes and fugues that would eventually make up his “Well-Tempered Clavier.”

In addition, the majority of his organ works were composed during his tenure in Weimar, and Bach performed them regularly in concerts at the court. Among Bach’s magnificent organ compositions, we find the Toccata and Fugue in D minor, BWV 538. This work is not to be confused with the Toccata and Fugue in D minor BWV 565, which has become a spooky Halloween favorite. In fact, BWV 538 carries the somewhat cryptic nickname “Dorian.” This particular nickname makes reference to one of the eight medieval church modes. If we were to play Dorian mode on a piano today, we would only use the white keys of the keyboard from D to D. And most importantly, there would be no key signature. And that is true of Bach’s “Dorian Toccata and Fugue,” as it is written without key signature. That means that the entire composition has an ancient modal, that is “Dorian” quality.

When Johann Sebastian Bach died on 28 July 1750, he left behind an incomplete musical work of unspecified instrumentation. The work consists of 14 fugues and 4 canons in D minor, and Bach scholars call it “an in-depth exploration of the contrapuntal possibilities inherent in a single musical subject.” It’s almost unbelievable, but Bach composed all these magnificent fugues and canon based on a single melody. This sounds simple, but it is in reality a highly complex process of rules and restrictions. Yet for the musical and expressive genius Johann Sebastian Bach, the possibilities within these restrictions were endless. He demonstrates every compositional technique and method known to him, but sadly the collection remained unfinished. While weaving his musical signature B-A-C-H into a 4-voice triple fugue on three subjects, Bach died. Today, The Art of the Fugue “stands as not only the ultimate monument to his own wide-ranging genius but an enduring shrine to the art of an entire epoch. Yet it is no dry memorial. Although incomplete, quixotic, and partly abstract, it has attracted, challenged, and enthralled musicians, scholars, and listeners of every era.”

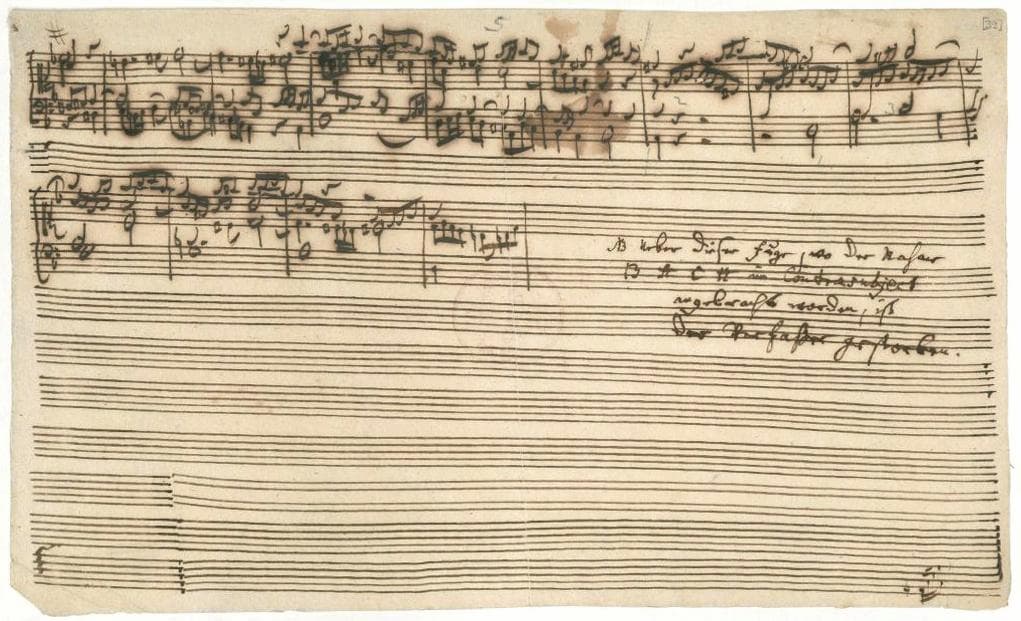

Bach’s unfinished fugue

We don’t exactly know why Bach started this collection at the end of his life, but it was written during a time when the musical style was undergoing a fundamental change. Counterpoint was being phased out in favor of an emerging homophonic style. As a Bach supporter wrote, “one very soon becomes tired of insipid little ditties that consist of nothing but consonances,” and a respected theorist praised the Art of the Fugue “as a bulwark against contemporary rubbish.” It seems that Bach wanted to make a musical statement, but what about the title? The earliest manuscript shows the following inscription on the title page, “Die Kunst der Fuga di Signore Joh. Seb. Bach.” However, that title page was written by Bach’s son-in-law Johann Christoph Altnickol. Did Bach dictate that particular title to Altnickol, or was that title common currency or simply a pointed nickname?

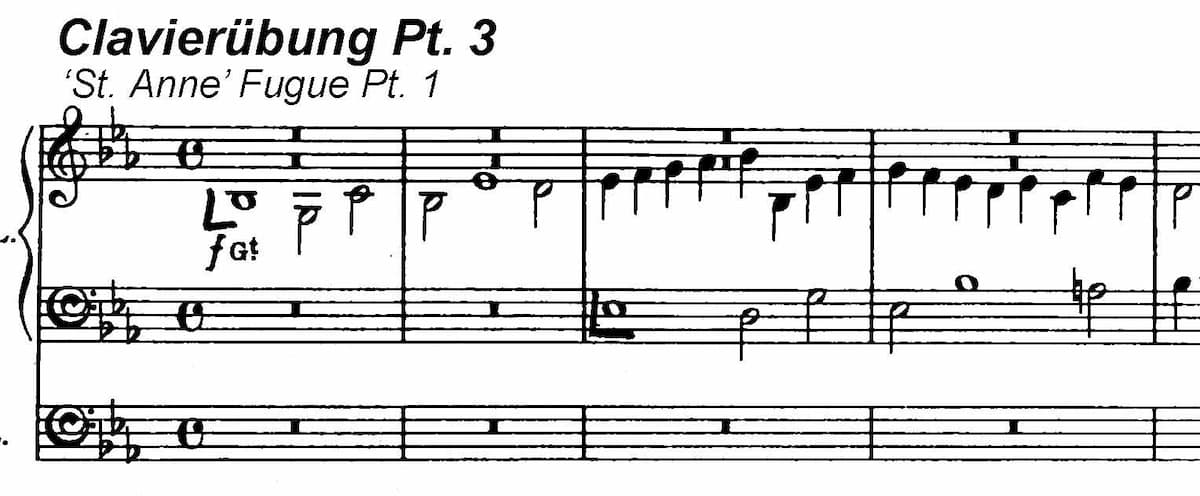

Johann Sebastian Bach, as we have already seen with the “Goldberg Variations,” wrote and published four sets of works under the title “Keyboard Exercises.” The third set, probably composed in 1739 opens with a huge Prelude in E-flat major followed by 21 chorale preludes, four duets, and a closing Fugue in E-flat major. As such, the prelude and fugue are not actually connected to each other. This only changed when Felix Mendelssohn told everybody that they should be performed as a single Prelude and Fugue in E-flat major.

Bach’s fugue “St. Anne”

The prelude is one of the largest organ pieces that Bach ever wrote, and the fugue features three subjects based on a common theme. That theme is similar in melody to William Croft’s hymn tune “O God our Help in ages past.” It is doubtful that Bach ever knew that particular hymn tune, but the nickname “St. Anne” for the E-flat fugue, attached in the 19th century, has stuck.

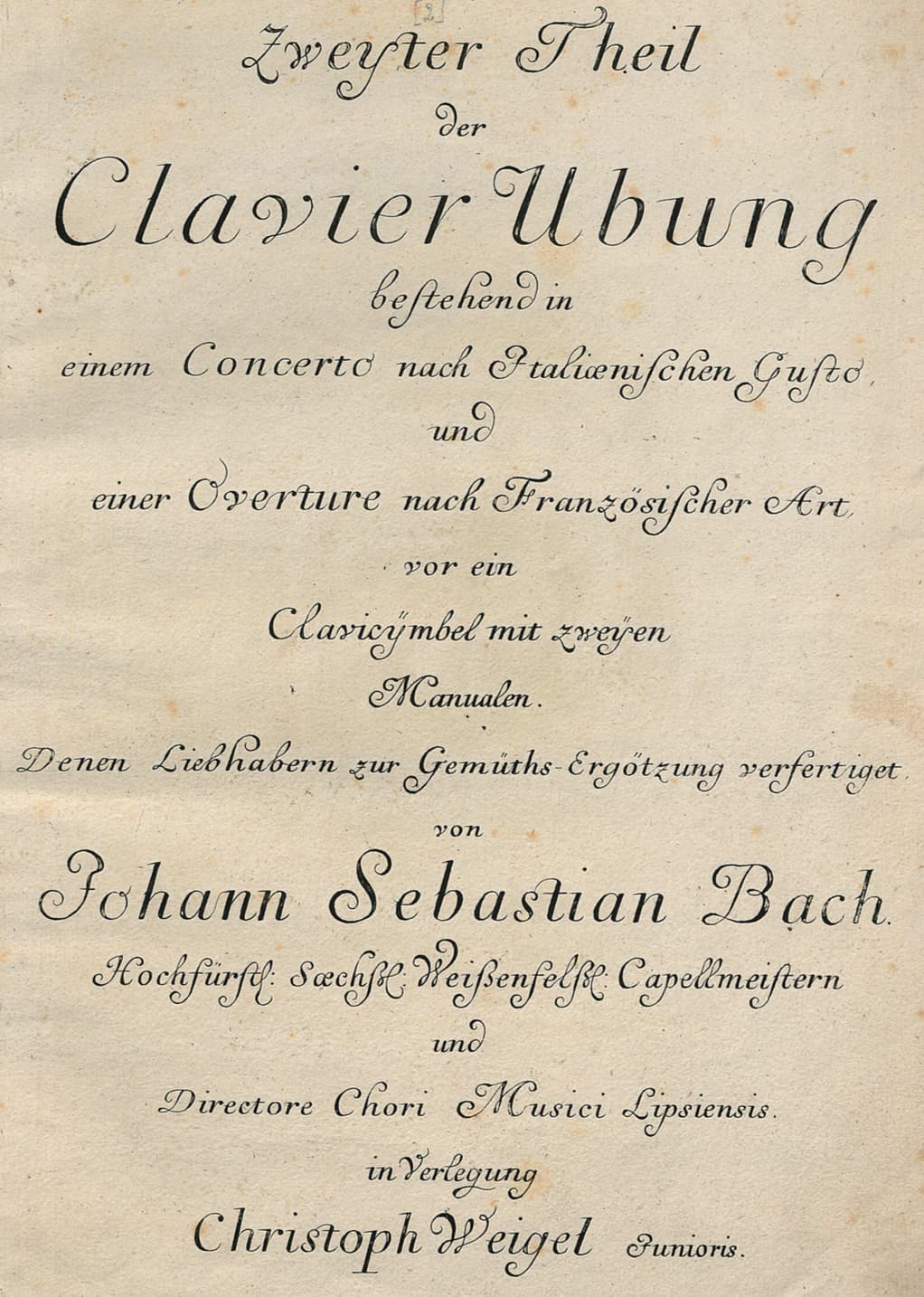

Let us stick to Bach’s “Keyboard Exercises” for our concluding example. The second part was published in 1735, and on the title page we read, “Keyboard Exercises consisting in a Concerto after Italian Taste and an Overture after the French Manner for a Harpsichord with Two Manuals, composed for Music Lovers, to Refresh Their Spirits, by Johann Sebastian Bach, Kapellmeister to His Highness the Prince of Anhalt-Cöthen and Director Chori Musici Lipsiensis.” Since Bach essentially composed a solo concerto in Italian style, the nickname “Italian Concerto” is not far-fetched.

Title page of Bach’s Keyboard Exercises Part 2

Even one of Bach’s greatest critics openly admired this work and wrote in 1739, “Finally I must mention that concertos are also written for one instrument alone…There are some quite good concertos of this kind, particularly for clavier. But pre-eminent is a clavier concerto of which the author is the famous Bach in Leipzig. Who is there who will not admit at once that this clavier concerto is to be regarded as a perfect model of a well-designed solo concerto? It would take as great a master of music as Mr. Bach provided us with such a piece, which deserves emulation by all our great composers and which will be imitated all in vain by foreigners.” Bach specified that the “Italian Concerto was to be performed on a two-manual harpsichord. In that way, he provides clear indications for softs and louds, for the keyboard interaction between the soloist and orchestra, and how the concerto was to unfold.

Thursday, March 9, 2023

The Look Of Love

Warsaw Concerto (Richard Addinsell)

Yvonne Elliman Hello Stranger HQ Remastered Extended Version

The Wonderful World of Classical Music: Great English Classics

Esther Abrami and Her Ensemble spotlight French composer, Louise Farrenc, for International Women’s Day

By Sophia Alexandra Hall

@sophiassocials19th-century French composer and equality campaigner Louise Farrenc sees her famed cello sonata reimagined for violin and string ensemble in a new arrangement by Esther Abrami and Her Ensemble.

For International Women’s Day 2023, TikTok classical music sensation Esther Abrami has platformed an underperformed French classical composer from the 19th century, with the help of Her Ensemble.

The composer in question is Louise Farrenc, a musician renowned in her time for her ‘well-written’ compositions, mastery of the piano, and professor position at the Paris conservatoire.

Despite being an accomplished artist in her own right, due to 19th-century attitudes, Farrenc was often addressed with backhanded compliments from reviewers. Symphonic composer Hector Berlioz once called her knack for orchestration “a talent rare among women”.

Her gender aside, Farrenc wrote some of the most ethereal earworms to emerge out of the 19th century, including her Cello Sonata, Op. 46 which Abrami and Her Ensemble have chosen to perform in celebration of the international day.

Listen to the sweeping ‘Andante Sostenuto’, the second movement from Farrenc’s sonata, arranged for solo violin and strings above.

‘Her music was so beautiful, I knew I had to play it’

On how she discovered the work, Abrami told Classic FM that she was looking for various pieces composed by women, and ended up finding Louise Farrenc. “I was listening to many of her pieces, and I heard this movement,” Abrami recalled.

“It was the kind of melody that you just keep singing once you’ve heard it, and I thought it was so beautiful and I knew I had to play it.”

Not only did Abrami play it, but the track features on her debut album, released with Sony Classical last year.

While the work was originally scored for cello and piano, founder and leader of Her Ensemble, Ellie Consta arranged the work for Abrami and her own string group.

“I’m actually pretty new when it comes to arranging,” Consta divulged to Classic FM. “During lockdown I started writing string parts for my friends who are artists and singer-songwriters, and really enjoyed that. Now I use these same techniques when arranging classical works.”

Consta, a graduate of Chethams School of Music, the Royal Academy of Music, and the Royal College of Music, felt comfortable arranging pieces for her new ensemble as she “knows strings”.

Consta continued, “I know them because I work in ensembles, orchestras, chamber groups all the time, so I know what each instrument sounds like, and I know how they work, and what passages are going to be uncomfortable under the fingers.

“Sometimes I can just text a friend and ask ‘is xyz ridiculous to play on a bass?’ or like with Esther, we had some conversations about what passages we should move up the octave.”

Abrami added that this is one of the advantages of working directly with an arranger when reimagining works.

“I think you need to have that two-way conversation between performer and arranger,” Abrami said, “When you’re going to be the one playing the composition, you can’t work with somebody who’s just gonna arrange a piece and not taking consideration your style of playing or your even your instrument abilities... though this actually happens so often.”

‘There were female composers in 450BC!’

Set up during the 2020 lockdown, Ellie Consta leads this mould-breaking group of musicians in a quest to address the gender gap and gender stereotypes in the music industry.

Consta decided to start Her Ensemble after reading a statistic from Donne, Women in Music that just 3.6 percent of the classical music pieces performed worldwide were written by women.

Over the past year this figure has risen, but only to 7.7 percent, and Consta and her group believe more needs to be done.

“It’s not that there aren’t female composers,” Consta enthused. “There are. All the way back to – and even before – the year 450 BC.”

One of these composers is 19th-century French composer, Louise Farrenc, a French composer, pianist and teacher who was born in Paris in 1804 and grew up surrounded by sculptors, painters and artistic women.

Studying piano from a young age, Farrenc’s musical gift was picked up on and encouraged by the likes of Clementi and Hummel, leading her to become interested in composition.

She gained a place at the prestigious Paris Conservatory at the age of just 15, wherein after she became a renowned concert pianist.

At the age of 38, Farrenc became the only woman to be appointed to the position of professor at the Paris Conservatory in the 19th century – the only such appointment for a woman for the entire 19th century.

She stayed at the conservatory for 30 years, over which time she became one of the greatest piano professors in Europe.

As well as being remembered for her exceptional musicianship and compositional abilities, Farrenc is today also remembered for her public push to be paid the same as a man would; a century before the ‘gender pay gap’ become a reported on issue.

Farrenc won the Académie des Beaux-Arts’ Chartier Prize for chamber music composition twice in 1861 and 1869. Though despite having these acclaimed works in her name, alongside a deeply impressive wider portfolio, her salary at the Paris Conservatoire remained lower than her male counterparts.

So, the 19th-century composer challenged this over a decade, protesting to senior academics at the institution. Her moment arrived however, after a performance of her Nonet at the conservatoire, which was well received. She used this performance as a chance to push again for a change in pay, and this time, she was successful.