by

Joseph Willibrord Mähler: Ludwig van Beethoven, ca 1804–1805 (Vienna Museum)

The Beethoven works that loomed the largest were his nine symphonies, especially the Third (composed between 1802 and 1804) and the Ninth (composed between 1822 and 1824).

These works were so revolutionary that many composers found it difficult to write orchestral works after them.

Brahms, for instance, knew that any symphony he’d write would inevitably be compared to Beethoven’s. He struggled for over twenty years to write his first symphony. And even after all that effort, he still couldn’t escape Beethoven’s shadow: Brahms’s First quickly earned the nickname “Beethoven’s Tenth.”

Interestingly, one of the surprising ways that composers engaged with Beethoven’s towering legacy was by completely – and creatively – reimagining his works.

Today, we’re looking at three major composers who rewrote the Beethoven symphonies.

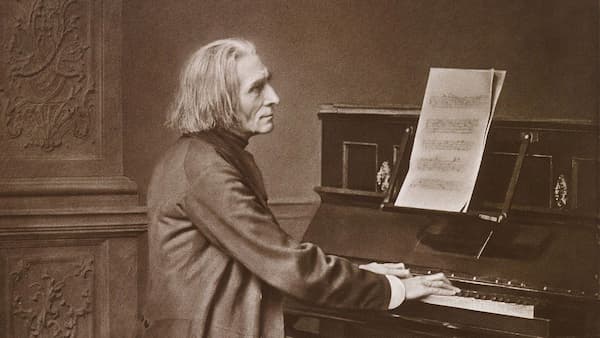

Franz Liszt Rewrites the Symphonies for Piano

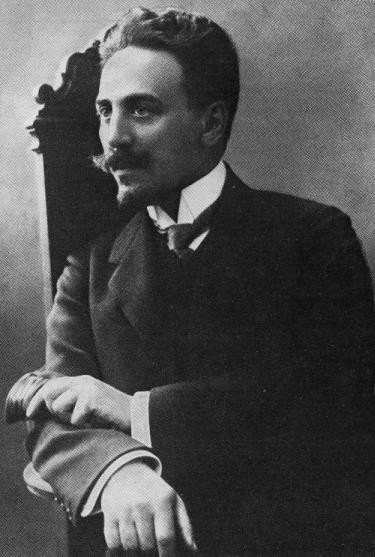

Carbon print circa 1869 by photographer Franz Hanfstaengl

Franz Liszt was born in 1811 and apparently met Beethoven as a young prodigy shortly before Beethoven died in 1827.

At the beginning of his career as a daredevil virtuoso pianist, Liszt would transcribe the fifth, sixth, and seventh symphonies for piano. Decades later, he would finally complete the set.

These transcriptions have a frenetic brilliance to them that makes for gripping listening.

In the 1960s, Glenn Gould became the first pianist to record the transcripts of the Fifth and Sixth symphonies. Gould described them before a radio broadcast:

According to a rather touching paragraph in Grove’s Dictionary, these keyboard extravaganzas were intended for his own use in towns which could boast no municipal orchestra, and before audiences which were otherwise without access to the symphonic milestones of Beethoven.

We have no such access problem these days, but Liszt’s transcription is much more than a tremolo-laden silent movie style period piece.

It’s not just remarkable as an archival curio, nor even as a typically Lisztian object lesson in the deployment of pianistic sonority, for even while it maintains an almost puritanical fidelity to the original text, it captures, I think, Liszt’s view of Beethoven, and, by implication, the attitude of the Romantic Age toward the classicist who unleashed romanticism.

In his pre-performance remarks, Gould verbalised a couple of reasons for Liszt to take on the project: to increase the symphonies’ accessibility in cities without orchestras, and to capture nineteenth-century ideas about the works for future generations.

Wagner Takes on Beethoven

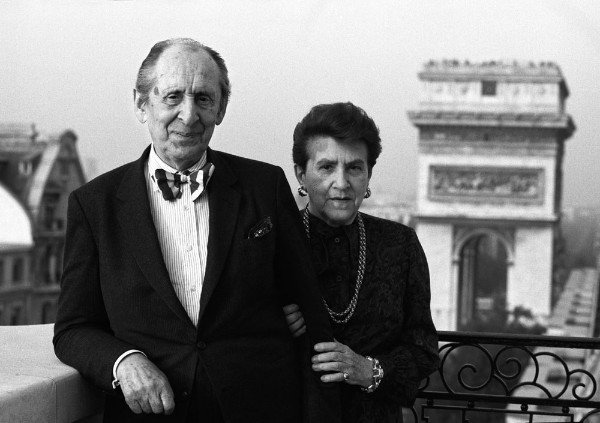

Richard Wagner

Composer Richard Wagner (1813–1883) was just a boy when Beethoven died.

He had recently fallen in love with music and was devastated by the loss. He later wrote about meeting Beethoven in his dreams, then awakening in tears.

In 1831, when he was still in his teens, Wagner made a transcription of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony for solo piano and voices. (Liszt had circumvented the difficulty of transcribing the choral part in the ninth by adding a second piano to his transcription.)

Wagner wrote of his attraction to the symphony:

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony became the mystical goal of all my strange thoughts and desires about music… It was considered the ‘non plus ultra’ of all that was fantastic and incomprehensible, and this was quite enough to rouse in me a passionate desire to study this mysterious work.

However, unlike Liszt, Wagner didn’t stop at a piano transcription.

In 1846, when he was working as a music director in Dresden, he mounted a performance of Beethoven’s Ninth. He prepared the local population for the performance by writing articles in the local newspaper.

He also altered the score. He believed that Beethoven wrote particular passages in certain ways because of his deafness or the limitations of earlier, more primitive instruments.

For instance, in bars 53-68 of the Scherzo, Wagner doubled a woodwind passage with brass.

Wagner also addressed the tempos of the symphony, encouraging musicians to discard the metronome markings that Beethoven had left behind, and taking the final two movements at almost half the speed of what Beethoven had indicated in the score.

(For a long time, conventional wisdom suggested that Beethoven’s deafness had made him incapable of judging the effects of the metronome markings, which many interpreters believed were too fast.)

Here’s a performance close to Beethoven’s stated metronome mark, as played by the Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra under Nicholas McGegan:

And here’s a Wagnerian tempo, as typified by the Vienna Philharmonic under Wilhelm Furtwängler:

The difference is stark.

Interestingly, Wagner also moved the chorus from in front of the orchestra to behind it: an arrangement that has been adopted in modern performances today.

Gustav Mahler Takes on Beethoven

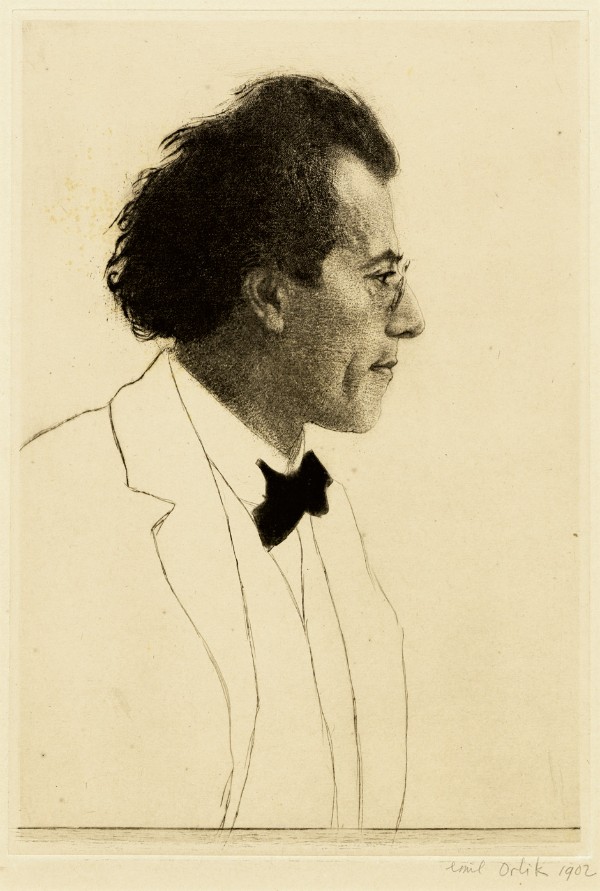

Gustav Mahler, 1902

Gustav Mahler (1860–1911) agreed with many of Wagner’s interpretive ideas. He was also in a position to put them into action after he became the conductor of the Vienna Philharmonic in 1898.

Mahler decided he wanted to modernise Beethoven’s symphonies to sound better in larger modern concert halls. Accordingly, he set about tinkering with the scores of all of them, save the Fourth.

Conductor Michael Francis, who has conducted a 2024 recording of these versions, says:

Mahler was concerned that in the turn of the 20th century that Beethoven’s classical language had lost some of the power. You think about some of the pieces that Strauss is writing; think of the pieces that Mahler was writing. So these are huge, big pieces, and he wanted Beethoven’s strength to be heard.

In order to create a bigger sound, Mahler doubled the winds and horns and even added a timpani player and tuba player.

In February 1900, Mahler debuted his new version of Beethoven’s Ninth.

Audiences were scandalised. Purists claimed they were upset because they valued Beethoven’s original score so highly, but the entire hullabaloo was also a convenient outlet for raging Viennese anti-Semitism.

The outcry became so loud that Mahler was forced to write an explanatory note in the press about his choices!

Judge for yourself; here’s the version of the Ninth Symphony that was so controversial.

In 2024, we published an article looking at his changes to Beethoven’s Third Symphony.

In 2020, we did an interview with conductor Johannes Vogel about what it’s actually like to perform these Mahler adaptations.

And here’s critic Dave Hurwitz sharing his opinions about the Mahler reorchestrations:

Conclusion

Every composer has to reckon with the shadow of Beethoven.

These three composers – Liszt, Wagner, and Mahler – did so in an especially intriguing way: by rearranging and rewriting his music, all for their own unique reasons.

Liszt wanted to be able to share Beethoven’s works with a wider audience. Wagner wanted to better understand his composer idol and translate Beethoven’s intentions for a new generation. Mahler continued that same mission where Wagner left off.

Whether you appreciate their work or not, it’s undeniable that each of these men made major contributions to Beethoven’s legacy. In the process, they proved the symphonies’ relevance and timelessness.