by Georg Predota

Vladimir Horowitz

“To tell you the truth, sometimes I’m frightened of myself,” he confessed in 1975, revealing the paradox of a genius who ruled Carnegie Hall but trembled at its threshold. This torment, born of revolution-scarred youth and relentless perfectionism, didn’t just haunt Horowitz.

Performance anxiety actually shaped his volcanic artistry, forging a legacy where fear and brilliance were inseparable. To celebrate his birthday on 1 October, let us honour the legacy of a pianist who transformed terror into transcendence.

Paradox of Genius and Fear

Born on 1 October 1903 in the shadowed streets of Berdichev, near Kyiv in what was then the Russian Empire, Horowitz emerged as a prodigy whose fingers danced across the piano with a ferocity that could coax thunder from ivory. His mother, Sophie, a conservatory-trained pianist, recognised his gift early, and by age 12, he was enrolled at the Kyiv Conservatory under masters like Felix Blumenfeld, a student of Tchaikovsky himself.

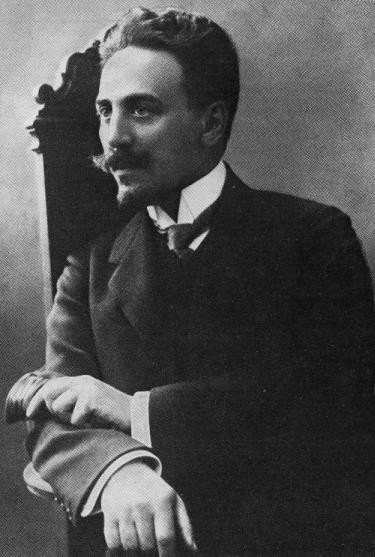

Felix Blumenfeld

Horowitz’s early career was a blaze of triumphs. Debuts in Leningrad and Kharkov in 1920, a European tour that stunned audiences in Berlin and Paris, and a New York recital in 1928 that prompted The New York Times critic Olin Downes to hail him as displaying “most if not all the traits of a great interpreter.”

Yet, beneath this virtuosic facade lurked a profound vulnerability. Stage fright, that spectral adversary, would hound him for decades. That insidious cocktail of adrenaline and dread afflicted Horowitz like a recurring fever. It manifested not as mere butterflies but as a paralysing panic.

Rituals of Dread

As biographer Glenn Plaskin recounts in Horowitz: A Biography, the pianist often arrived at venues in the eleventh hour, demanding silence from all around him, his anxiety so acute that aides sometimes had to physically nudge him toward the stage.

“Such was his stage fright that he often had to be pushed physically onto the stage,” notes music historian Robert Greenberg, underscoring how this neurotic ritual became as much a part of Horowitz’s lore as his octave-spanning arpeggios.

Incredibly, this man who commanded sold-out halls and fees that made him the highest-paid artist of the 1940s chronically doubted his own adequacy, whispering to himself that he was “inferior and inadequate” even as ovat

Murmurs of Assurance

The roots of Horowitz’s affliction might well be traced back to his tumultuous youth.

The 1917 Russian Revolution ravaged his family, as his father’s electrical engineering firm was seized, and relatives were imprisoned or executed. By 1925, the family had fled to Paris, leaving Vladimir to perform ragtime in silent-film theatres for survival.

This upheaval instilled a deep-seated insecurity, compounded by his innate perfectionism. “His consistent need to be perfect… drove his stage fright in a big way,” observed a scholar, also noting that the young pianist’s early acclaim only amplified his fear of failure.

Horowitz himself hinted at this inner turmoil in rare interviews, though direct quotes on stage fright are elusive. Instead, he channelled it into mantras of reassurance. Before performances, he would murmur, “I know my pieces,” a self-soothing litany affirming his meticulous preparation as a bulwark against the void.

A Vanishing Act

Vladimir Horowitz in 1931

This ritual, born of desperation, revealed a man wrestling not just with notes but with the terror of exposure. Horowitz’s first major retreat came in 1936, a seismic event that rippled through the music world. At the peak of his powers, fresh off collaborations with Toscanini and recordings that refined the Rachmaninoff concertos, he succumbed to “nervous exhaustion.”

Married since 1933 to Wanda Toscanini, daughter of the imperious conductor Arturo, Horowitz faced mounting pressures. The stormy union was marked by Wanda’s infidelities and Vladimir’s alleged homosexuality, with colitis twisting his gut.

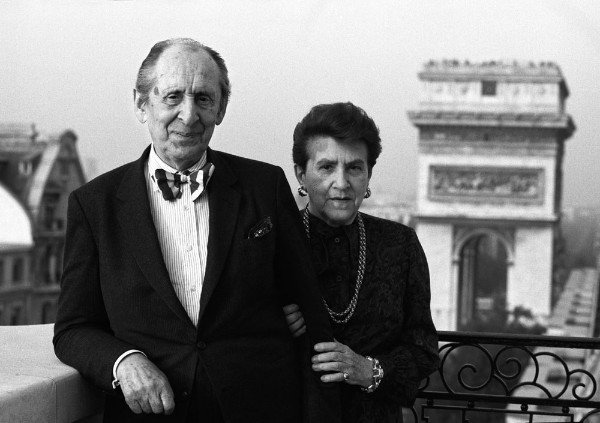

Vladimir and Wanda Horowitz

He vanished from the stage for 13 months, retreating to Italy and then New York, where therapy and rest barely quelled the storm. Biographer Harold C. Schonberg, in Horowitz: His Life and Music, describes this period as one where “the heartbreaking destruction of his family combined with… professional frustrations to bring on the first of several breakdowns.”

Electric Return and Enduring Shadows

Upon return in 1938, his playing was electric, but the fright lingered like a shadow. The post-World War II years amplified the torment. By 1953, after a separation from Wanda and rumours of institutionalisation, Horowitz hit rock bottom.

He underwent electroshock therapy for depression, a brutal intervention that left him catatonic at the piano. “For months, for years, he was incapable of performing in public,” recounts author Lea Singer in a 2021 interview about Horowitz’s hidden life.

The mere thoughts of the stage triggered panic attacks so severe that rumours started to fly that he could no longer touch the keys. This hiatus lasted 12 years, the longest of his four periods of retirement. During these silences, Horowitz turned to recordings, a much safer harbour where he could edit out imperfections.

A Phoenix Rises

Vladimir Horowitz in 1986

Yet, from these ashes rose phoenix-like comebacks, each a testament to resilience. The most mythic unfolded on 9 May 1965, at Carnegie Hall. Backstage, Horowitz paced like a caged tiger, his wife and daughter, Sonia, imploring him to move forward. When he finally emerged, the ovation was deafening.

His program, scarred on showpieces and heavy on Bach, Clementi and Mozart, unleashed a Horowitz reborn. His playing was introspective, crystalline, with rubato that breathed like wind through willows. Pianist André Watts captured the onstage atmosphere, stating, “Horowitz was like a demon barely under control.” (Read more about “Vladimir Horowitz’s Legendary 1965 Carnegie Hall Comeback Concert“.)

The eminent musicologist Charles Rosen elaborated further, dubbing performance anxiety “a divine ailment, a sacred madness. It’s a Promethean curse where the artist suffers to deliver the divine spark.”

Imperfect Perfection

Horowitz transmuted performance anxiety into daring, as the fear of errors became the edge that sharpened his interpretations. As he explained in 1975, “I must tell you I take terrible risks. Because my playing is very clear, when I make a mistake, you hear it… Never be afraid to dare.”

Yet, Horowitz disdained mechanical perfection. “Perfection itself is imperfection,” he quipped, instead favouring “a little mistake here and there” to infuse music with human warmth.

Lea Singer described his offstage demeanour as a “shy penguin”, noting his 1986 Moscow bow tie, and grinning through “great sadness.” Pianist Oscar Levant, another anxiety-plagued musician, jested that Horowitz should advertise “for a limited number of cancellations.”

Tears and Triumph

Vladimir Horowitz in 1986

Critics and peers dissected Horowitz’s affliction with awe and empathy. In The Guardian, a 2015 reflection on overcoming anxiety likened stage fright to “an untamed horse. We have to try to harness it, let it out, pull it back,” an apt metaphor for Horowitz’s volatile command.

Even in later years, as recordings supplanted tours, his influence endured. His late-career resurgences, in 1978 in Cleveland after a nine-year absence, and the 1986 historic Moscow return amid Gorbachev’s glasnost, were defiant rebuttals to his demons.

As he plays Schumann’s Träumerei with tears in his eyes, an encore that bridges across 61 years of exile, he once declared, “without false modesty, I feel that, when I’m on the stage, I’m the king, the boss of the situation.” Yet, as Classical Music magazine reflected in 2025, his “success… came at a heavy price, with electroshock scars and pill bottles as collateral.”

Chasing the Sublime

Vladimir Horowitz died on 5 November 1989, in New York, felled by a heart attack at the age of 86. His legacy, etched in 25 Grammys and the Presidential Medal of Freedom, transcends the man. Performance anxiety for Horowitz was no mere malady but the crucible of his art.

It forced retirements that honed his depth, risks that electrified his touch, and returns that redefined triumph. In an era when beta-blockers offered chemical relief, as proposed in a 1979 Times article, Horowitz reminds us that the raw edge of fear can give birth to the sublime.

As Joan Acocella, in her 2015 The New Yorker essay on performance anxiety, wrote, “Horowitz played from the other side of the score, looking back.” And maybe that’s how we should gaze at him as well. A demon tamed, a king enthroned, forever chasing the music behind the notes.

No comments:

Post a Comment