Today we’re going to talk about symphonies.

What exactly is a symphony? Is it different from a sinfonia?

And, depending on your answer to that question, which composer has written the most symphonies of all time? And how many symphonies did that person write?

Keep reading to find out. The answers might surprise you!

Joseph Haydn (1732–1809)

104 Symphonies

Joseph Haydn

If you love classical music, you know Haydn would be on this list!

Joseph Haydn was born in rural Austria in 1732. He went on to become one of the most celebrated composers of the Classical era.

A major part of his reputation rests on his output of symphonies.

He wrote his first surviving symphony in 1759. Haydn’s First is in three movements: a slow movement bracketed by two fast movements. A typical performance takes about fifteen minutes.

He wrote his final symphony, numbered 104 and nicknamed the London, in 1795. This symphony demonstrates how far Haydn pushed the boundaries of the genre over his career.

The work has four movements (Adagio-Allegro, Andante Minnuet and Trio, and a finale marked “Spiritoso”) and takes about half an hour to perform.

Nowadays, we think of a symphony as a four-movement work for orchestra, at least half an hour in length. Haydn’s creative evolution over the course of writing a hundred-plus symphonies contributed to that perception.

Christoph Graupner (1683–1760)

113 Sinfonias

Christoph Graupner

Of course, Haydn’s development also leaves us with the question: should early orchestral sinfonias that aren’t as long as later symphonies count?

Music historians can argue the question, but for the purposes of this article, we’re going to say yes!

That’s why the next figure on our list is Christoph Graupner, who was born in 1683 (three years after Bach) in Saxony. He studied law in Leipzig, then music with Johann Kuhnau. Kuhnau was the music director of the renowned Leipzig-based Thomanerchor choir before Bach took the job.

Graupner spent most of his career at the court in Hesse-Darmstadt, where he worked between 1709 and 1754, when he went blind.

He wrote 113 sinfonias.

Here’s a recording of a particularly striking example. It’s a six-movement work composed for orchestra and six timpani.

Derek Bourgeois (1941–2017)

116 Symphonies

Derek Bourgeois

Derek Bourgeois was a British composer born in 1941. He studied at Cambridge and the Royal College of Music.

Early in his career, he worked as a lecturer, youth orchestra conductor, and director of music at St. Paul’s Girls School in London. He also composed extensively and was especially noted for his works for brass and wind band.

He wrote his first symphony when he was eighteen, in 1959. He had seven to his name by 2001, when he retired.

However, during retirement, he kept composing. By 2009, he revealed in an interview with The Guardian that he was up to 44 symphonies. That marked him as the most prolific symphony writer in British history.

And these works weren’t short, either. That Guardian article reported: “The average length of a Bourgeois symphony is 47 minutes.”

Remarkably, as he grew older, he only became more prolific. Between 2009 and his death in 2017, he added a shocking 72 more to his tally, for a grand lifetime total of 116!

Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf (1739–1799)

120+ Symphonies

Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf

Composer Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf was born Johann Carl Ditters in Vienna in 1739.

As a child, he studied the violin and eventually became a professional violinist. In 1771, he became the court composer at Château Jánský Vrch, in the present-day Czech Republic.

He was eventually promoted and received the noble title that transformed his name to Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf.

Dittersdorf wrote around 120 symphonies. Interestingly, he wrote twelve programmatic symphonies before the concept was popular, all inspired by Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Unfortunately, only half of them survive today.

Johann Melchior Molter (1696–1765)

140+ Symphonies

Johann Melchior Molter

Johann Melchior Molter was born near Bach’s hometown of Eisenach, sixteen years after Bach.

Much like Bach, records about Molter’s early training are scarce. Historians do know that by his early twenties, he had left Eisenach to take a job as a violinist in Karlsruhe.

Soon after, he decided to travel to Italy to continue his music studies. He lived there for two years, then returned to Karlsruhe, where he became Kapellmeister at the court there. In 1734, he accepted a job as Kapellmeister at the court of Duke Wilhelm Heinrich of Saxe-Eisenach.

Over the course of his career, he wrote 140+ symphonies and sinfonias.

These were written before Haydn and his generation revolutionised the genre, so most of them are only around ten minutes long and don’t adhere to the symphonic form as codified in the Classical era.

Still, this is exciting, attractive, striking music.

František Xaver Pokorný (1729–1794)

140 Symphonies

František Xaver Pokorný

František Xaver Pokorný was born in the town now known as Stříbro, Czech Republic.

He left to take lessons in Regensburg in present-day Germany. During the 1750s, he worked and studied in the cities of Wallerstein and Mannheim (where the virtuosity of the court orchestra would inspire a variety of eighteenth-century composers).

In the later part of his life, Pokorný returned to work at the court of Regensburg.

It is believed that over the course of his career, he wrote over 140 symphonies. However, after Pokorný died in Regensburg, fellow composer and court orchestra intendant Theodor von Schacht erased Pokorný’s name from his works and reattributed them to other composers, making certain identification difficult.

And without further ado, here is the composer who has written the most symphonies ever, by far…

Leif Segerstam (1944–2024)

371 Symphonies

Leif Segerstam

Leif Segerstam was born in Vaasa, Finland, in 1944. His family moved to Helsinki when he was a boy, and he studied violin and conducting at the Sibelius Academy there. He then finished his studies at Juilliard in the United States.

Between 1995 and 2007, he served as conductor of the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra. He also enjoyed an international conducting career.

Segerstam also composed and became famous for his 371 symphonies.

His first symphony – subtitled “Symphony of Slow Movements” – was written in the late 1970s. Beginning in 1998 with his 23rd symphony, he started writing multiple symphonies a year until 2023, ending with a grand total of 371.

Most of these symphonies last for around twenty minutes and are one movement long. Many feature unusual titles like “Symphonic Thoughts after the Change of the Millenium No. 1”, “Listening to the tree clapping your shoulder…”, and “Calling the 112 in woody galaxies of the multiverses….”

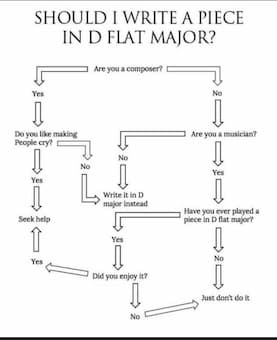

“What? D-Flat Major?” Most string players wail, “that’s a key signature with FIVE FLATS!”

“What? D-Flat Major?” Most string players wail, “that’s a key signature with FIVE FLATS!”