It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Saturday, July 30, 2022

Percy Faith & His Orchestra - A Summer Place - 1959

Friday, July 29, 2022

Love Is A Many Splendored Thing (모정.慕情) - The Film Studio Orchestra & An...

Thursday, July 28, 2022

World Athletics long jump champion is also a classical pianist with a passion for Chopin and Schubert

By Siena Linton, ClassicFM

Malaika Mihambo, an Olympic and world champion long jumper, plays classical piano in her downtime.

Born in Germany in 1994, Malaika Mihambo is one of the greatest long jump athletes competing today.

She currently holds the titles of Olympic, world, and European champion in her sport, most recently winning the gold medal at the World Athletics Championships in Eugene, Oregon on 24 July.

This recent win marks her second gold medal at the competition, having taken home first place in the 2019 event in Doha, Qatar, as well as Olympic gold at Tokyo 2022. She also won the gold medal at the 2018 European Championships, which usually take place every two years but were cancelled in 2020 due to the global pandemic.

Like many athletes, Mihambo has several methods for de-compressing and relaxing after competitions and rigorous training sessions, and one of her great passions outside of athletics is classical music.

In an interview with the German magazine Concerti, Mihambo reveals that she didn’t discover classical music until 2016. She began playing the piano aged 22, and through her learning of the instrument began to delve deeper into the genre.

“Musicians and athletes have a lot in common”, Mihambo says. “Diligence, discipline and passion, which you have to show in order to achieve good results and progress, are particularly important’’.

The German athlete also says she enjoys learning at her own pace without the pressure of success, as a sort of contrast to her thriving career in competitive sport.

In a post shared to Instagram, Mihambo is pictured at her piano with a book of music by Chopin, captioned “Music is a universal language. It give you emotions and something to think about. It’s definitely soul food”.

Mihambo also shared a short clip from Franz Schubert’s Sehnsuchtswalzer as she prepared for the European Indoor Championships, in February 2022:

From ‘Nessun dorma’ at the 1994 World Cup to Ravel’s Boléro soundtracking the most memorable ice dancing final in history, classical music and sport have long been intertwined. Discover the most famous examples here.

73-year-old conductor collapses and dies mid-performance at leading German opera house

By Sophia Alexandra Hall, ClassicFM

@sophiassocialsStefan Soltész is the fourth conductor to collapse during a performance at the Bavarian State Opera over the past century.

Hungarian-born Austrian conductor, Stefan Soltész collapsed at the podium of the Bavarian State Opera on Friday evening, and died later that night.

The 73-year-old maestro passed out towards the end of the first act of Strass’ Die schweigsame Frau (The Silent Woman) which he was conducting at the Munich based opera house.

Over the weekend, the Bavarian State Opera released a statement on its website reading, “It is with shock and deep sadness that the Bayerische Staatsoper has to announce the loss of Stefan Soltész.

“He passed away on the evening of July 22, 2022 after collapsing during his conducting of Die schweigsame Frau by Richard Strauss at the Nationaltheater. Our thoughts are with his wife Michaela.”

Serge Dorny, the opera company’s general director, tweeted on Friday night that, “We are losing a gifted conductor, and I have lost a good friend.”

Read more: Tragedy at Moscow’s Bolshoi Theatre as actor killed on stage

After Soltész’s fall, the opera came to a halt, with an immediate 30-minute interval called for the audience. When the audience returned after the break, the state opera’s artistic operations manager, Tillmann Wiegand, announced that the production had been cancelled.

Soltész was seen by the on-site doctor at the theatre, before being rushed to hospital where he was pronounced dead later that night.

The maestro is the fourth conductor to collapse mid-performance at the Munich based opera house. In 1911 the 56-year-old Austrian conductor, Felix Mottl, collapsed while conducting his 100th performance of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. He died 11 days later.

In 1968, the 60-year-old German conductor Joseph Keilberth died at the podium during a performance of the same opera. And in 1989, the 57-year-old Italian conductor, Giuseppe Patanè collapsed while conducting Rossini’s The Barber of Seville. Patanè was pronounced dead at a hospital just hours later.

Read more: Concert pianist who suffered heart failure during a concerto performance, has died

Artists across Europe and beyond have taken to social media to mourn the death of Soltész over the weekend.

Born in 1949, Soltész trained in Vienna before going on to lead the Aalto Theatre in Essen to international acclaim as the opera house’s artistic director. He was also the music director of the Essen Philharmonic, and earned a Grammy nomination for an album he directed with the ensemble.

The Strauss opera Soltész had been conducting was a revival of a 2010 production by Australian opera director, Barrie Kosky. The two artists had worked on numerous projects together throughout Germany.

On learning of Soltész’s death on saturday morning, Kosky shared his grief and told the New York Times that the conductor was “an amazing musician”, and “the real thing”.

Tuesday, July 26, 2022

Monday, July 25, 2022

Großbritannien richtet 2023 für die Ukraine den ESC aus

Quelle: Luca Bruno/AP/dpa

Die Ukraine wird den ESC 2023 nicht ausrichten – die Sicherheitsbedenken sind wegen des Kriegs zu groß. Das zweitplatzierte Großbritannien wird einspringen. Dennoch ist man dort traurig, dass der ESC wegen des „andauernden russischen Blutvergießens“ nicht in der Ukraine stattfinden könne.

Das zweitplatzierte Großbritannien wird im kommenden Jahr anstelle des diesjährigen ESC-Siegers Ukraine, den Eurovision Song Contest ausrichten. „Nach der Anfrage der European Broadcasting Union und der ukrainischen Behörden freue ich mich, dass die BBC zugesagt hat, den Wettbewerb im nächsten Jahr auszurichten“, sagte die britische Kulturministerin Nadine Dorries am Montag. Allerdings sei es traurig, dass der ESC aufgrund des „andauernden russischen Blutvergießens“ nicht in der Ukraine stattfinden könne, dort wo er eigentlich hingehöre.

Mitte Mai hat die ukrainische Gruppe Kalush Orchestra mit dem Lied „Stefania“ in Turin den 66. ESC gewonnen. Damit hatten die Ukrainer zum dritten Mal das Recht auf die Austragung der TV-Musikshow im kommenden Jahr erlangt, schon 2005 und 2017 waren sie Gastgeber gewesen.

Doch wegen Sicherheitsbedenken im Zusammenhang mit dem seit rund fünf Monaten andauernden russischen Krieg gegen die Ukraine teilte die Europäische Rundfunkunion (EBU) mit, Gespräche mit der BBC in Großbritannien über die Austragung zu führen. Der Brite Sam Ryder hatte in Turin den zweiten Platz belegt. Unklar ist bisher, in welcher Stadt der Wettbewerb ausgetragen wird. Manchester und Glasgow haben Interesse signalisiert, wie die BBC berichtete.

Der britische Premierminister Boris Johnson hatte sich vor einem Monat für eine Austragung des nächsten Eurovision Song Contest in der Ukraine ausgesprochen. „Tatsache ist, dass sie ihn gewonnen haben, und sie verdienen es, ihn zu haben“, sagte Johnson damals.

Sunday, July 24, 2022

'The Phantom of The Opera' Sarah Brightman & Antonio Banderas

Saturday, July 23, 2022

Cavatina from the Deer Hunter

Friday, July 22, 2022

Thursday, July 21, 2022

15 glorious pieces of classical music for summertime

By Maddy Shaw Roberts, ClassicFM

Let these brilliant summer melodies take you on a musical journey from the fervent height of summer, to the tranquil sunset at day’s end.

Keep cool and ring in the sun-drenched months ahead with these chilled classical melodies, courtesy of Vivaldi, Albéniz, Gershwin and more.

Marquez – Conga del Fuego

This fantastically energetic work is a frantic, joyous dance – impossibly catchy in its rhythms, a new classical favourite of the last ten years or so and an immediate reminder of the euphoria of summer.

Delius – On Hearing the First Cuckoo in Spring

Based on a melody from an old Norwegian folk song ‘In Ola Valley’, this beautiful tone poem is among English composer Delius’ most beloved pieces. Listen out as instruments of the orchestra imitate the natural sounds of the cuckoo – from the strings to the woodwind.

Tereso Carreño – Mi Teresita (Little Waltz)

Here’s a delightful ditty for solo piano, written by 19th-century Venezuelan concert pianist and composer Teresa Carreño for her daughter, Teresita. At her concerts, Carreño often played this charming piece as an encore.

Gershwin – Summertime

It started as an opera aria from Porgy and Bess, and then became a reggae hit, and finally a jazz staple. Gershwin’s sultry writing with a hint of melancholy has lent itself to every genre imaginable, making ‘Summertime’ the most covered song in the world.

Respighi – The Pines of Rome

Glimmering with anticipation from the offset, this delightful orchestral tone poem opens with a musical painting of children playing in the pine groves and closes with trumpet fanfares to depict a marching band.

Beethoven – Romance No. 2 in F major

Warmth practically radiates out of this Romantic violin work – sublime, and yet somewhat sad in its innocence and sweetness, as we remember that Beethoven composed the piece while coming to terms with the tragedy of his deafness, probably for the first time.

Debussy – Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune

This delightful symphonic poem tells the tale of the mythical faun who, enchanted by the woods’ nymphs and naiads, drifts off to sleep. Don’t be surprised if Debussy’s famous chromatic opening flute solo and shimmering harp lines send you off into your own slumber, as they emulate the languorous heat of a summer afternoon.

Rodrigo – Concierto de Aranjuez

Journey to Spain’s sweltering capital with this beautiful classical guitar concerto, filled to the brim with swelling melodies and melancholic emotion, all while bringing to life the aristocratic essence of an 18th-century court.

Mendelssohn – A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Within Shakespeare’s tranquil yet playful setting, Mendelssohn places a sweeping Intermezzo, enchanting Nocturne and a rather impish Scherzo. This music is an exquisite listen during the warmer months.

Camille Pépin – Apaisé, boisé

Rising star French composer Camille Pépin’s gently pulsating work for orchestra induces a state of dreamlike musical bliss. It practically sings of summer and new growth, as the woodwind, brass and strings each take it in turns to pierce the earth and find sunlight.

Glazunov – The Seasons

Glazunov’s ballet The Seasons creates four tableaux based on the changing seasons, and ‘Summer’ speaks to a delightfully rural scene. As water is brought to refresh the flowers, which have been basking in the warmth of the sun, the Spirit of the Corn dances in thanksgiving. Is that the picture of summer, or what?

William Grant Still – Summerland

A gentler choice now, this heavenly work by William Grant Still – the first African American composer to conduct a major US symphony orchestra – is the second movement in a three-part solo piano suite, which tells the story of a human soul’s journey after death. If the life has been a good one, the soul may enter ‘Summerland’.

Richter – On the Nature of Daylight

Modern composer Max Richter’s deeply beautiful, reflective ‘On the Nature of Daylight’ has lent perfectly to cinematic use. A calming, contemplative work for gentle reflection, as the sun sets on the day.

Listen here to Classical Summertime, our live playlist on Global Player.

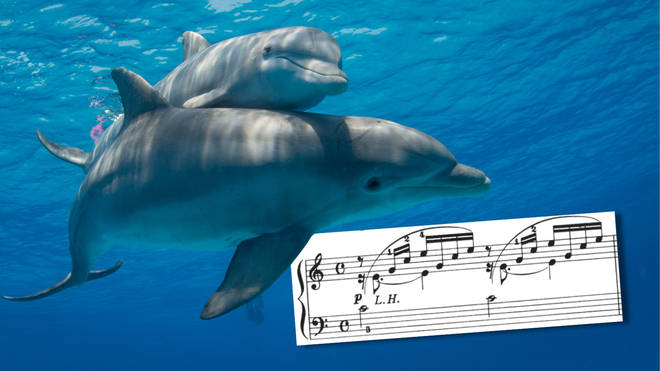

Dolphins behave better after listening to Bach and Beethoven, study finds

By Sophia Alexandra Hall, ClassicFM

@sophiassocialsBeethoven’s ‘Almost a Fantasy’ and ‘The Swan’ by Saint-Saëns are just some of the pieces of classical music enjoyed by Italian dolphins involved in this latest scientific study.

Most scientists agree that dolphins are very intelligent creatures. The species have demonstrated in multiple studies that they are quick learners, empathetic, self-aware, and great at problem solving.

But a recent study published in the journal Applied Animal Behaviour Science has now proved that dolphins are also music lovers, and that classical music specifically could improve social behaviours of the aquatic animals.

Researchers at the University of Padua in Italy found that playing classical music resulted in the dolphins showing more interest in each other, giving more gentle touches and swimming in synchrony for longer.

Eight dolphins in the eastern beach-front city of Riccione, Italy, were played 20 minutes of classical music a day via an underwater speaker for seven sessions. The aquatic mammals heard a number of pieces of classical music including Bach’s Prelude BWV 846, Grieg’s ‘Morning Mood’ from Peer Gynt, Debussy’s Reflets dans l’eau, Beethoven’s Almost a Fantasy, and ‘The Swan’ from The Carnival of the Animals by Saint-Saëns.

On other days, the dolphins were played the sound of rainfall for 20 minutes (auditory stimulus), given floating toys to play with for 20 minutes (an already known form of enrichment for the animals), or shown natural environments on television screens for 20 minutes (visual stimulus).

The group of dolphins was made up of five female and three male dolphins between the ages of five and 49 years old. Three of these dolphins, which are housed at a dolphinarium in Riccione, were born in the wild.

The researchers found that only the music had a long-lasting positive effect on the dolphins’ behaviour. As only classical music was used, the researchers admitted the results may not be specific to just the classical genre, but that classical music could be particularly useful when improving social behaviours in dolphins.

The use of music was also a particularly useful tool for when the animals were under stress or in situations that could lead to increased conflicts.

Lead researcher Dr Cécile Guérineau said the way the dolphins acted, suggested they were showing happiness.

“This system is linked to reward, social motivation, pleasure and pain perception,” explained Dr Guérineau. “Activation of opioids receptors is correlated with a feeling of euphoria. [And] we know that in a wide range of animals – from mammals, monkeys, dogs, rats etc, to non-mammals, birds – endorphins, i.e. one type of endogenous opioids, are related to social bonding.

“Dolphins may also be able to perceive rhythm because they are a vocal-learning species. It may be that, similar to how dancing at a party makes us feel good and helps people to bond, when dolphins synchronize to a beat, they also feel good and connect with their fellow swimmers.”

GIRL FROM IPANEMA

Cole Porter song EVERYTIME WE SAY GOODBYE and his life and music

Wednesday, July 20, 2022

"Somewhere In Time" - Complete Soundtrack

John Dunbar Theme - Dances with Wolves

Out Of Africa | Soundtrack Suite (John Barry)

Monday, July 18, 2022

Make Friends With the Music

by Frances Wilson , Interlude

© Jordan Mixson on Unsplash

Too often it seems that we view learning, studying, practising and performing music as a kind of fight. People talk about “doing battle with Beethoven” or “fighting the fear” (of performing) as if one must take up arms against unseen, powerful forces.

Beethoven: Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 61 – III. Rondo: Allegro

It’s true that learning new repertoire can be a Herculean task, and practising can feel like a form of captivity, the same page of music confronting one day after day, coupled with the sense that one has hardly moved forward from the previous day’s practising. It is also true that in order to learn any repertoire properly, and deeply, we must spend inordinate amounts of time sweating the small stuff – all the details in the score, the directions and signposts the composer gives us to navigate the keyboard and produce a coherent path of sound to take the listener on a unique journey into the composer’s own inner landscape, while also to enabling us to make our own interpretative choices about how we will perform the music.

There is no alternative to the hard graft of learning new work in depth: working, with pencil and score, cutting through the music to the heart of what it is about. Living with the piece to find out what makes it special, studying style, the contextual background which provides invaluable insights into the way it should be interpreted and performed. The endless striving to find the emotional or spiritual meaning of a work, its subtleties and balance of structure, and how to communicate all of this to an audience as if telling the story for the very first time.

Studying, practising performing and ultimately sharing music, the musician’s “work”, should not feel like a battle or a mountain summit that must be conquered. I know many musicians, professional and amateur, who have personal strategies to prevent this sense of struggle. Spending time with the score away from the instrument can be particularly helpful, familiarising the shape and architecture of the music on the page, and imagining the sound in one’s head, without the added distraction of the geography of the piano keyboard, for example. For very complex music, I like to leave the score, or copies of the score, around the house – on the dining table, by my bedside, so that I see the score regularly, often many times during the day. When I come to place it on the music desk, it already feels comfortable, even if I have yet to touch the piano’s keys.

Practising is an act of doing, creating, living with the music. It defines who we are as musicians and gives us a reason for being. A positive, open minded approach to practising can remove the feelings of toil and travail. Making friends with the music brings joy, pleasure and excitement to practising. We should live and breathe our work, beginning every practise session with the question “What can I do that’s different today?”.

This excitement and affection for our music is very palpable when we perform – audiences sense and appreciate it – and it brings the notes to life with vivid colour and imagination.

Saturday, July 16, 2022

The Prodigal Pianist

by Frances Wilson, Interlude

Alan Rusbridger

The adult ‘returner’ pianist

I’m a returner pianist – and maybe, if you’re reading this article, you are too and therefore what follows will resonate with you. Or perhaps you are thinking of taking up the piano again after a long absence (as I did), in which case you should definitely read on…..

I played at a piano club recently and during the coffee break someone asked me if I was “a professional pianist”. This gave me a momentary glow of pride and ego – evidently I had played well and “made an impression” – and I know that many amateurs dream of reaching the dizzy heights of ‘professional standard’ in their playing. It’s one of the things that keeps us motivated to practice; alone with that box of wood and wires we dream of playing to a full house at the Wigmore or Carnegie Hall.

So I replied that no, I was an amateur pianist, an adult ‘returner’ and that I had given up the piano at the age of nineteen when I left home to go to university, returning to it just shy of my fortieth birthday with an all-consuming passion for the instrument, those who play it and its vast and varied literature.

When you tell people you’ve taken up the piano again they always ask, “Are you any good?” And I never know quite what to say. Some days when my spirit and fingers are in sympathy with each other, I think I make a reasonable sound. On other days, spirit and fingers aren’t on speaking terms and the result is fumbling, dismal, depressing.

– Alan Rusbridger, journalist and amateur pianist

The world of the adult amateur pianist is a curious one – at once rich, vibrant and varied, but also obsessive, anxious and eccentric and when I put out a call for contributions to this article, I was deluged with responses as varied, fascinating and moving as the literature of the instrument we play. What follows are just a few of the responses, but what they demonstrate is that, while there are some obvious common threads, the reasons for returning to and playing the piano are often deeply personal and hugely meaningful, and that a passion for the piano is all-consuming. Never forget that the word “amateur” derives from the Old French word meaning “lover of” from the Latin amator: all the amateur pianists I meet and know play the piano because they love it and care passionately about it. Love drives commitment to the instrument – amateur pianists are possibly the most dedicated practicers – and many amateurs are absorbed by a compelling need to get better, to progress, to master. It’s a lonely road to travel, but those who commit to the journey do so willingly, and it’s an ongoing process, one which can provide immense satisfaction, stimulation and surprising creativity.

Amateur pianists at La Balie piano summer course

That is not to say that professional pianists don’t love the piano too – of course they do, otherwise they wouldn’t do it, but a number of concert pianists whom I’ve interviewed and know personally have expressed a certain frustration at the demands of the profession – producing programmes to order, the travelling, the expectations of audiences, promoters, agents etc, which can obscure the love for the piano. Because of this, professionals are often quite envious of the freedom amateur pianists have to indulge their passion, to play whatever repertoire they choose and to play purely for pleasure.

Now, back to those inspiring adult returners…..

My primary reason for returning was that both my parents had lived the last ten or twelve years of their lives with advancing dementia, as well as some second degree relatives. I thought the best way to really work my brain was to go back to playing music. The secondary reason was to help relieve stress which was something my piano teacher had told me I would need at some point in my life……For me, having started to suffer the lacunar strokes in my family history which have a type of dementia related to them, I keep hold on the fact that the part of the brain that works with music is usually the last to fail. I still feel that playing the piano is probably one of the best avenues to take to keep working the brain. Apart from that I simply love playing again.

– Eleanor

It was the death of an uncle which prompted me to return to the piano. He was very musical, and after he died my other uncle asked me whether I would like his piano, a rather fine Steinway grand which had been in the family for ages. However, grand pianos are somewhat incompatible with the three bedroom semi in which I live, but it did remind me how much I’d enjoyed the piano. I was lucky enough to be left some money in his will, and with that I bought a Yamaha upright with silent system fitted. I wanted a proper acoustic, but I have young children so a silent system means I can practice at night after they are in bed. I have lessons once a fortnight and they are completely indispensable for my enjoyment.

– Sarah

I studied music at university and did two years of a performance major but struggled with various chronic injuries and dropped out as a result (I had two operations and had seen many medical specialists in attempt to resolve these problems). I then “sold my soul” to capitalism and started a business, following which I continued along a corporate career. I had always dreamed of getting back into playing but my schedule was punishing and not at all conducive to playing. I started to play again and unfortunately ended up with RSI (tennis elbow) which swiftly ended my return to playing. Then a few years later I managed to extricate myself from the corporate world and…..I managed to start playing again and although I had some niggles from the RSI, was able to play around 0.5 – 1 hrs a few days a week. I also started going for lessons with [a teacher who] focussed very much on reducing tension…..and I realised how much of my injuries came down to poor technique and tension. I wish a greater emphasis had been placed on this when I was a music student because while [my teacher] helped me find a much more natural, comfortable way to play, it was already too late and my RSI flared up again to the point where a few minutes of playing would leave me in agony for days. It was devastating after so long of trying to be in a position to have the time to play that I wasn’t able to. A few years later (whilst consistently seeing medical specialists and trying various approaches) I managed to have a breakthrough in which I was able to slowly start playing again, a few minutes every second day and was able to gradually build up. This was a useful exercise in that I had to be more focussed on practising effectively given the limited time available. Despite being told by numerous doctors that I wouldn’t play again, I’m now able to play for up to an hour on some days. This has been sufficient to learn some new repertoire and to perform in some amateur meet-up groups which has really been a wonderful experience. In fact, once I was able to let go of the inner critic (as a former music student, the inner critic remains highly developed even though one’s technical ability wanes without practice!), I couldn’t believe how much I enjoyed playing. It would have never have occurred to me all those years ago when I dropped out of university that I’d be able to derive so much enjoyment out of playing as an amateur.

– Ryan

I originally started piano lessons aged 13, of my own volition; I’d had one of those 80s electronic keyboards that were all the rage back then, and wanted to progress to something more substantial. My progress was very slow, however, and ultimately not very fulfilling. I managed to pass my Grade 1 but found the exam experience stressful. I think a lot of it had to do with the prescriptive way children are typically taught: everything was just scales, sight reading and set pieces that weren’t especially fun or engaging to play. Nearly twenty years later, I was in a piano bar on holiday, and the pianist was playing modern music set to piano. It was beautiful, and I felt a sense of regret that I had abandoned such a beautiful instrument. On returning home, I did a spot of research and found that digital pianos had come on a long way in the intervening years and were now touch-sensitive with weighted keys and even a sustain pedal. I took the plunge, ordered a decent model (the Yamaha P115) and signed up for lessons with a local teacher. It’s been a wonderful decision, and I have fallen in love with playing. It’s still small steps, but I practice regularly and have actively witnessed improvement in my own playing.

– Colin

I discovered classical music as a teen (Bach) and started taking lessons. I wanted to be a composer, and eventually became a composition major at a local university. Having started late, and not having received family support and good advice from those who did support me, I let my insecurities defeat me, and I ended up getting a degree in English. Decades later, we inherited a spinet from a relative, and I found my passion once again. I finally have a good teacher, and am making progress toward being the pianist I wanted to be.

– Bob

My piano journey has been relatively straightforward compared to some of the accounts of other adult returner pianists, but we are all on our own personal path, some of us supported by teachers, others choosing to “go it alone”, but all driven by a common, consuming passion for the piano.