It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Popular Posts

-

84,201,796 views Oct 7, 2015 #HindiKoKaya #VinaMorales #DeniseLaurel Listen and watch the Official Lyric Video of "Hindi Ko Kaya...

-

13,907,441 views Nov 11, 2010 No description has been added to this video. Music 1 songs C'era una volta il west (Finale) Ennio Morr...

-

by Janet Horvath “What? D-Flat Major?” Most string players wail, “that’s a key signature with FIVE FLATS! ” I don’t blame them. It’s so mu...

-

1.- "Fanfare" - 14.05.2002 & 15.05.2002 in "Stadthalle", Zwickau (Germany). 2.- Medley: "Bésame mucho"/ ...

-

Mikhail Glinka: "Ruslan and Lyudmila" Overture (with Score) Composed: 1837–42 Conductor: Mikhail Pletnev Orchestra: Russian Nation...

-

12,036,418 views Mar 23, 2023 #musicevolution #evolutionofmusic Timestamps: Ancient Music ( 00:00 ) Medieval Music ( 02:56 ) Renaissan...

-

James Inverne Tuesday, July 1, 2025 James Inverne on why he was drawn to write a play about a scandal around the writing of two rival La b...

-

by Georg Predota Kurt Masur, 1968 For well over three decades, Kurt Masur was one of the world’s most celebrated conductors, having establis...

-

285,684 views Mar 11, 2024 "La Vie En Rose" Emmet's Place Miami Live 2024 Emmet Cohen - Piano Shelly Berg - Piano Cyrille ...

-

by Hermione Lai The 68 string quartets by Joseph Haydn revolutionised chamber music and earned him the title “Father of the Strin...

Total Pageviews

Friday, July 18, 2025

James Last orchestra & singers: " The world of the gentleman of music", ...

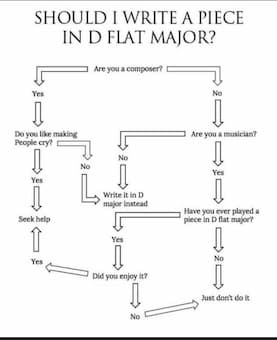

Why D-Flat Major Should Be One of Our Favorite Keys

by Janet Horvath

“What? D-Flat Major?” Most string players wail, “that’s a key signature with FIVE FLATS!”

“What? D-Flat Major?” Most string players wail, “that’s a key signature with FIVE FLATS!”

I don’t blame them. It’s so much more difficult to play in tune on string instruments without the resonance of the open strings.

Pianists, though, will be elated. They get to play on all of the black keys. Numerous composers have used D-flat major to depict lush, dreamy sounds, and to explore the richness and depth of expression imaginable in this key.

Perhaps you know that many composers associated specific emotions with certain keys. The key of E-flat major is a case in point, a key that is considered heroic. Think Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3 The Eroica, Strauss’ Ein Heldenleben, a Hero’s Life, and dozens of string quartets and symphonies by Haydn, Sibelius, Elgar, Dvořák, Mozart, Bruckner, Shostakovich, Mahler.

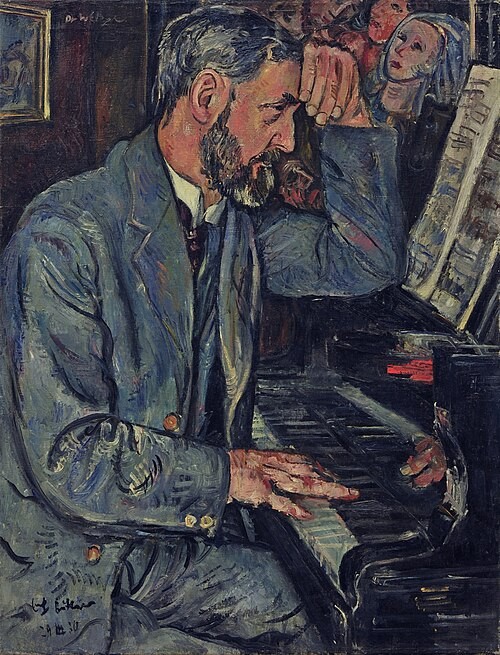

Frédéric Chopin © Getty Image

One of the most famous piece for piano in D-flat is the Chopin Prelude Op. 28 No. 15 “Raindrop.” Chopin did not ascribe the name to this prelude. It begins hushed and pensive, and the affecting melody leaves us in a subdued mood. It turns suspenseful, becoming more chordal and powerful. The right hand continues the inexorable rhythm and generates the feeling of inevitability with its repeated and steady A-flats that seem to imitate raindrops. But the opening melodic line returns reassuring us, and the piece resolves peacefully. Whatever you imagine when you hear it, there is no denying the emotions generated.

Jean Sibelius

Romance in D-flat is an exquisite piece by Sibelius. Upon first hearing, you might think it’s a work of Chopin and I wouldn’t blame you. It’s amorous with flourishes and emotions you would associate with Chopin. Sibelius is not necessarily known as a solo piano composer. Ten pieces make up Sibelius’ Opus 24, composed between 1895 and 1903, and they are stunning. Diverging from his huge symphonic works puzzled Sibelius’ children too who asked him why he wrote these solo piano works, he responded, “In order for you to have bread and butter.”

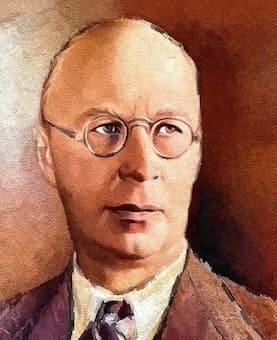

Sergei Prokofiev © Esoterica Art Agency 2018

Written in 1901 as a birthday gift, the D-flat major Romance has been published and performed separately. The Andantino opens with a two-bar chordal introduction in the right hand with a lyrical cello-like melody entering in the left hand. It’s gorgeous. The middle section becomes vibrant and agitated with octaves and chords marked with accents on each note, and the instruction, “forte crescendo possible.” A cadenza with rapid notes, is breathtakingly dramatic. The magnificent resonance achieved in this piece is due in part to the pianist flying all over the black keys.

Prokofiev Piano Concerto No. 1, Op. 10 was composed in 1911, and is dedicated to the Russian composer, pianist, and conductor, the “dreaded Tcherepnin” with whom Prokofiev worked at the St. Petersburg Conservatory. Although the piano concerto is only fifteen minutes long, in one movement, Prokofiev marked eleven distinct sections of varying tempos and disposition. From charm to the grotesque, every mood is depicted. The piece begins as it ends with an expansive, yearning, and deliberate theme in D-flat major with heart-thumping punctuation in the timpani. Electrifying octaves in the piano bring the piece to a finish.

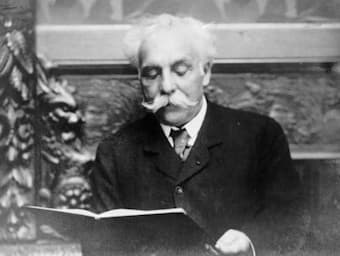

Gabriel Fauré

Gabriel Fauré Cantique de Jean Racine, Op. 11 is a work for mixed chorus and piano or organ, with lyrics by the 17th-century poet Racine. A version for strings and harp is breathtaking. The text “Verbe égal au Très-Haut” or Word One with the Highest, is from a Latin hymn “O Light of Light” attributed to the fourth century bishop of Milan, St. Ambrose. The refined and sublime piece hints at the music of the Requiem Fauré composed later in life. Only 20 years old when he composed this piece, we are assured of his position as one of the greatest composers of French choral music when we hear the Cantique. A dazzling lilting melody opens the piece. The chorus enters with the lowest voices first and gradually expands to include the higher voices. After another interlude of the instruments alone, Fauré continues this technique and we experience a ravishing series of colors, dynamics, and textures, enhanced by the resounding key of D-flat.

Antonín Dvořák

Dvořák Scherzo Capriccioso Op.66 B.131, is an orchestral work composed in 1883. The D-flat major key allows the composer to explore not only the Czech folk music we usually expect but a more dark, opaque, and restless mood. Featuring a full complement of instruments such as the harp, triangle, English horn, and bass clarinet, Dvořák achieves a brilliant variety of tone colors and wondrous melodies, his forte. The English horn solo is especially poignant.

Amy Beach © Amybeach.org

Some composers actually see colors when he or she hears certain keys or pitches, a condition called synesthesia, in other words the perception of one sense through another. Amy Beach was one of these composers and D-flat major, for Beach, represented the color violet, traditionally associated with wealth, royalty, and the divine. The first section of her 1925 work Canticle of the Sun a cantata for chorus, soloists, and orchestra Op. 123, sets a thirteenth century text by St. Francis of Assisi. The piece begins Lento con Maesta, with the feelings of searching, of hesitancy, and then bursts into the key of D-flat major—the strong D-flat major chord used on the word “God” imbuing the word with wonder and veneration. The use of the key here is powerful as well as opulent.

I’m convinced and I hope you are too. D-flat major should be considered one of our favorite keys!

On This Day 18 July: Kurt Masur Was Born

by Georg Predota

Kurt Masur, 1968

For well over three decades, Kurt Masur was one of the world’s most celebrated conductors, having established an international reputation as “a sensitive and innovative interpreter of the Classical and Romantic repertoire, specifically Mendelssohn, Brahms and Tchaikovsky.” He was also known as the most prominent musician from communist East Germany. Masur never joined the Communist Party, and he was a thorn in the side of communist leadership. Masur declined repeated offers to leave East Germany, and instead became actively involved in the cause for freedom. In 1989, growing anti-government protests shook the city of Leipzig, and Masur publically criticized the violence by riot police against the demonstrators. On 9 October 1989, he read a public appeal for freedom of discussion in the socialist state. His appeal is widely regarded as helping convince Leipzig police to disregard orders from Berlin and allowed the protests to continue. “In the same century that saw two world wars, I was witness to a peaceful revolution,” he told reporters. The Berlin Wall fell in 1990 and led to the reunification of Germany, with Masur mentioned as a possible candidate for the German presidency. He declined, “I am a musician, not a politician,” he said. “I was only one among many people who overcame their fear.”

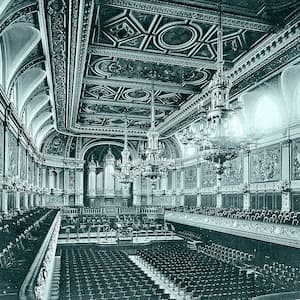

Interior of the Gewandhaus, 1886

Kurt Masur was born on 18 July 1927 in the city of Brieg, Silesia, now Brzeg, Poland. His father was an electrician, and he was destined to follow in his father’s footsteps. However, it became clear early on that his true passion and happiness lay in music. He taught himself to play the piano as a young child, and initially studied piano and cello at the Landesmusikschule in Breslau. Once he returned from conscription to the Second World War, he entered the University of Music and Theatre in Leipzig and studied composition and piano. However, Masur quickly specialized in conducting, “despite suffering from a nervous stutter.” He discontinued his studies in order to take up the position of répétiteur and staff conductor at the Halle Landestheater in 1948 and was subsequently first Kapellmeister at the city theatres of Erfurt and Leipzig, and conductor of the Dresden Philharmonic Orchestra and the Komische Oper of East Berlin. In 1970 Masur received the crowing appointment of his early career: music director of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, a position he would hold for 26 years.

Kurt Masur laying the foundation stone of the current Gewandhaus

In the early 1970s, Leipzig was the industrial center of the communist run German Democratic Republic. The city’s main concert hall, the fabled Gewandhaus had been completely destroyed during the Second World War, and it had not been rebuilt nor restored. During his first year of tenure in Leipzig, the Gewandhausorchester was housed in a convention hall near the city’s zoological garden. Masur recalled, “When the music was quieter you could hear the lions roar…we were on the verge of embarrassing ourselves.”

Modern Gewandhaus, 1981

Masur made it his mission for his orchestra to be taken seriously, and he wrote to Erich Honecker, the leader of the GDR’s ruling Socialist Party. Masur campaigned for a new concert hall and recognizing the cultural and symbolic importance of the Leipzig Orchestra, the GDR leader authorized the construction of a new venue. The “Neue Gewandhaus” was opened in commemoration of the 200th anniversary of the orchestra taking up residence in the original Gewandhaus, on 9 October 1981. While in Leipzig Masur was credited with restoring a vanished glory to that ensemble and city’s musical life, “and made recordings of Beethoven (including a complete cycle of the symphonies), Mendelssohn, Bruckner, and Brahms, praised for their clarity, unforced expressiveness, and warm, cultivated sonorities.”

Kurt Masur and his family, 1981

Despite the political challenges, Masur was allowed to take his orchestra on international tours, culminating in a performance at Carnegie Hall in 1974. The visit turned out to be prophetic as Masur was named the music director of the New York Philharmonic in 1991. As in Leipzig, Masur was charged with rebuilding the orchestra from the ground up. The ensemble, once considered one of the premiere American orchestras, “had devolved into a lackluster group: critically skewered, internally contentious and lacking clear artistic vision.” A critic wrote, “Before Mr. Masur arrived, the Philharmonic’s reputation was justly at a low point. Audiences were disenchanted. The players had long been unhappy; recording engagements were hard to come by, and radio broadcasts were nonexistent. Symphonic music was becoming less important to the culture of New York. The orchestra’s status had so fallen that the director’s post was rejected by major maestros.” A former concertmaster explained in 2012, “He was just so demanding and intense, and by the sheer intensity of his personality, it sorts of transformed most of us.” Masur’s tenure with the New York Philharmonic represents “one of its golden eras, in which music-making was infused with commitment and devotion, with the belief in the power of music to bring humanity closer together.” Masur once famously said, “If every school would hire two more music teachers, we would need two fewer police officers on the streets.”

Joseph Haydn: 10 Most Ingenious String Quartets

by Hermione Lai

Joseph Haydn

Written primarily between the 1750s and 1790s, these works showcase his ingenuity, featuring sparkling melodies, intricate counterpoint and really clever structural surprises.

Drawing from Haydn’s extensive catalogue is no easy task, but we’ve selected 10 of Haydn’s most ingenious string quartets. That selection is based on their musical inventiveness, historical significance, and influence on subsequent generations of composers.

So let’s get started with his Op. 20 set of string quartets, representing Haydn’s early experiments that defined the conversational nature of the genre.

String Quartet in D Major, Op. 20, No. 4, Hob. III:34 (1772)

The six “Sun” quartets of 1772 shook up the classical music world in 1772. Haydn was in his late 30s and working for the Esterházy family. The Op. 20 quartets came at a time when Haydn was pushing boundaries, blending the elegance of the gallant style with the emotional depth of the “Sturm und Drang” literary movement.

Op. 20 No. 4 was written for four skilled players, so Haydn could be adventurous. He treated all four instruments, two violins, viola, and cello, like equal partners. This was pretty radical as the first violin would normally hog the spotlight.

This quartet is not a solo act, but a conversation. It’s funny, tender, and clever all at once. It’s like friends jamming together, trading ideas and laughs. This quartet is the perfect entry point in the wonderful and human world of Joseph Haydn.

String Quartet in F Minor, Op. 20, No. 5, Hob. III:35 (1772)

Compared to the sunny D-Major quartet, the Op. 20 No. 5 in F minor has a darker and more introspective character. It reflects the “storm and stress” trend at the time, putting a premium on dramatic and emotional intensity.

The opening movement is especially intense, unfolding from a brooding theme through a number of intricate motivic developments. There is plenty of lyrical melancholy in the slow movement, and just listen to the double fugue in the finale. After all, Haydn was a master of counterpoint.

This timeless gem is so emotionally rich. It is a musical journey through tension, calm, and eventual revolution. And you certainly need expert musicians to bring out the raw energy and nuance, mixing depth and accessibility.

String Quartet in E-flat Major, Op. 33, No. 2, Hob. III:38, “Joke” (1781)

The Opus 20 quartets turned Haydn into a superstar in the musical world. One decade later, he further refined the genre with more polish and playfulness in his Op. 33 set. As Haydn himself said, these works were written in “a new and special way.”

The Op. 33 are often called the “Russian” quartets, because they are dedicated to the Grand Duke Paul of Russia. Some scholars theorise that these quartets might have been the inspiration for the six Mozart string quartets dedicated to Haydn.

The most famous of the set earned the nickname “Joke” because of the mischievous ending of the Finale. However, the entire quartet is packed with Haydn’s trademark humour and surprises. It is light-hearted yet sophisticated, showcasing the composer’s ability to make complex music feel effortless. Just goes to show that classical music does not have to be deadly serious.

String Quartet in G Major, Op. 33, No. 5, Hob. III:41 (1781)

Another gem from the Op. 33 set is the quartet No. 5 in G Major. It sometimes carries the nickname “How Do You Do?” for its quirky and conversational opening. This quartet presents a perfect blend of elegance, wit, and warmth.

Haydn called the Op. 33 “new and special,” likely because of their polished structure, lyrical themes, and the equal roles for all four instruments. Each movement has its own character, from the musical handshake of the opening to the warm and lyrical slow movement. The Scherzo is a lively dance with a rustic edge, and the Finale is a set of variations on a simple and catchy tune with folk-song character.

Op. 33 No. 5 is a crowd pleaser because of its sunny glow, catchy themes, and some subtle humour. It’s a perfect blend of sophistication and fun, full of infectious energy and momentum.

String Quartet in D Major, Op. 64, No. 5, Hob. III:63, “The Lark” (1790)

Nicknamed “The Lark” for its soaring and birdlike melody in the opening movement, the string quartet Op. 64, No. 5 represents a polished example of Haydn’s ability to blend the emotional depth of his earlier works with a polished and accessible style that greatly appealed to audiences.

This quartet is less experimental than his Op. 20 but more refined than Op. 33, showcasing Haydn’s mastery of balance. We find catchy tunes, a tight structure, and it’s a performer’s delight and a listener’s joy.

Each movement has its own personality, from the chatting bird in the opening to a slow movement of pure warmth. The minuet has a playful spin, and the high-energy Finale is like a musical game of hot potato. It certainly sparkles with clarity and charm.

String Quartet in D Minor, Op. 76, No. 2, Hob. III:76, “Fifths” (1797)

The six quartets of Op. 76 are ambitious late works with advanced forms and thematic unity. Composed in 1797, they are among Haydn’s final and most celebrated contributions to the genre.

At the age of 65, Haydn was a global superstar, having returned from his triumphant tours to London. This trip had given him new ideas, and he now blended technical brilliance, emotional depth, and a highly polished style that appealed to both players and audiences. And the Op. 76 No. 2 is a masterpiece, bold, emotional, and packed with Haydn’s wit and wisdom.

Nicknamed “Fifths” for the stark and descending fifth motif in the opening movement, the work opens with a tense and conversational energy. The warm D Major in the slow movement provides a lyrical and playful breather, but the Menuetto is back in the minor key. Sometimes it is nicknamed the “Witches Minuet.” The Finale is a whirlwind based on a fiery, folk-inspired theme.

String Quartet in C Major, Op. 76, No. 3, Hob. III:77, “Emperor” (1797)

Nicknamed “Emperor” for its majestic second movement, Op. 76 No. 3 is one of Haydn’s finest works in the genre. It is a masterpiece of balance, juggling grand, lyrical and humorous elements in a clear and approachable style.

The “Emperor” nickname comes from the second movement, a set of variations on Haydn’s anthem “God Save Emperor Francis,” composed in 1797 as a patriotic response to Napoleon’s rise. The simple and noble melody undergoes four variations that transform the theme while keeping its dignity completely intact.

The opening movement is a burst of energy, sounding a bold and fanfare-like theme in the first violin. And just listen to the sudden pauses, harmonic twists, and playful interplay between all four instruments. The minuet has a rustic edge while the Finale is once more a high-octane affair.

String Quartet in B-flat Major, Op. 76, No. 4, Hob. III:78, “Sunrise” (1797)

Another gem in the Op. 76 set is the string quartet in B-flat Major, No. 4. It earned the nickname “Sunrise” from the opening of the first movement. A soaring violin melody rises over a gentle accompaniment, resembling the sun peeking over the horizon.

It is a magical moment that sets a joyful tone. The mood quickly turns playful with a bouncy second theme and lively interplay between the four instruments. The slow movement, in turn, is a soulful gem, with a tender and hymn-like melody that is almost orchestral in texture. Intimate and heartfelt, it provides a moment of quiet reflection.

The minuet is again a rustic dance with Haydn adding quirky offbeat accents and dynamic shifts to keep it cheeky. What a charming mix of elegance and earthiness. And then there is the infectious rhythm of the rollicking Finale. Op. 76 No. 4 is a work of sheer beauty and charm, blending accessibility with sophistication.

String Quartet in D Major, Op. 76, No. 5, Hob. III:79 (1797)

Op. 76, No. 5 in D Major is a radiant and lyrical work that is often considered among Haydn’s finest string quartets. Known for its serene and songlike qualities, this quartet does not have a catchy nickname, but its warmth and elegance make it a standout.

It is a gem for its lyrical and balanced structure, and certainly more introspective and serene. The sunny D Major feels like a warm embrace, and Haydn once again blends sophistication with charm and vibrant energy.

The heart of this quartet is the deeply expressive slow movement scored in the unusual key of F-sharp Major. Sounding a unique and glowing warmth, the melody is soulful and expansive, with a touch of melancholy. It’s like a private confession, both tender and profound. On account of this movement, some commentators have called it the “Graveyard Quartet.”

String Quartet in G Major, Op. 77, No. 1, Hob. III:81 (1799)

Haydn playing a string quartet

Let us conclude this blog on the 10 most ingenious string quartets by Joseph Haydn by featuring his Op. 77, No. 1. It represents a vibrant and polished work that sounds the culmination of Haydn’s quartet writing.

This work was among his final contributions to the genre he helped to perfect. This quartet is the culmination of his craft, blending the emotional depth of his late style, the polish of his London visits, and his lifelong love of surprise and interplay.

The opening movement presents a flowing theme in the first violin contrasted by a dance-like second theme. The slow movement is a lyrical gem, and the minuet is full of musical mischief. The folk-inspired theme of the Finale is passed among the quartet like a musical relay, and the high-spirited finish simply makes us smile.

Joseph Haydn mastered the string quartet genre by transforming it into a dynamic and conversational form where all four instruments share equal roles. From the Op. 20 to the Op. 77, he blends structural brilliance with emotional depth and incredible humour. Haydn set the standard for the quartets of Mozart, Beethoven, and beyond.

In Memory of the Past: Goethe’s ‘Erster Verlust’

by Maureen Buja

| Erster Verlust | First Loss |

| Ach wer bringt die schönen Tage, | Ah, who can bring back the beautiful days, |

| Jene Tage der ersten Liebe, | Those days of first love, |

| Ach wer bringt nur eine Stunde | Ah, who can bring back even one hour |

| Jener holden Zeit zurück! | Of that lovely time! |

| Einsam nähr’ ich meine Wunde | Lonely, I nurse my wound |

| Und mit stets erneuter Klage | And with ever-renewed lament |

| Traur’ ich um’s verlorne Glück. | I mourn for lost happiness. |

| Ach, wer bringt die schönen Tage, | Ah, who can bring back the beautiful days, |

| Jene holde Zeit zurück! | That lovely time! |

Joseph Karl Stieler: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe at age 79, 1828 (Neue Pinakothek)

Johann von Goethe (1749–1832)’s poem entitled ‘Erster Verlust’ (First loss) was first written in 1785 for his Singspiel Die ungleichen Hausgenossen (The Unequal Housemates), intended to be an aria for the Baroness, in Act II. The play was never completed, sidetracked, perhaps, by Goethe’s plans for his upcoming Italy trip. Luckily, he salvaged the poem (and two others) and included them in his Schriften of 1789. For the Schriften printing, Goethe wrote stanzas 2 and 3 anew.

Because of its small size and simple expression, the poems became a favourite of many composers, with some 50 setting it to music. We will look at the song and its setting over the century from 1813 through 1919. In this 8-line poem, Goethe expresses that painful memory of what was lost when one’s first love is no longer your love. There’s no idea of death, but rather hints of decisions made, time lost, and a mourning for the past.

Carl Friedrich Zelter (1758–1832) was one of Goethe’s favourite composers and became the poet’s musical advisor. He was a detailed chronicler of musical events of his time, and his letters are a prime source of information about significant events, such as the famed 1812 meeting of Beethoven and Goethe. Organised by Bettina Brentano, the two men met in the Bohemian spa town of Teplitz. As expected, they did not agree with each other’s self-assessment: Beethoven thought the poet too loving of the court atmosphere, and Goethe thought the composer had ‘an absolutely uncontrolled personality’. Goethe was 63 years old and Beethoven a mere 42.

Zelter wrote over 200 lieder, 75 of them to texts by Goethe. He detailed his thoughts on lieder writing in a letter to the composer Carl Loewe: the text must take priority, the strophic song is to be preferred to ‘absolute through-composing’, and the accompaniment must stay in the background.

Goethe, for his part, had his musical demands, the primary of which was that the music should support the poet’s words. This led Zelter to write music that was plain and strophic, even when the textual manner was more emotional. The music serves the poet’s words, and we can understand why Goethe was so taken with him. Famously, Goethe preferred Zelter’s setting of the poem Erlkönig, rather than the more dramatic setting by Schubert that is so well known today.

The song was published in 1813 as part of Zelter’s collection of 48 sämmtliche Lieder, Balladen und Romanzen; the four-volume collection was in its second edition by 1816.

Carl Begas: Carl Friedrich Zelter, 1827 (Sing-Akademie zu Berlin)

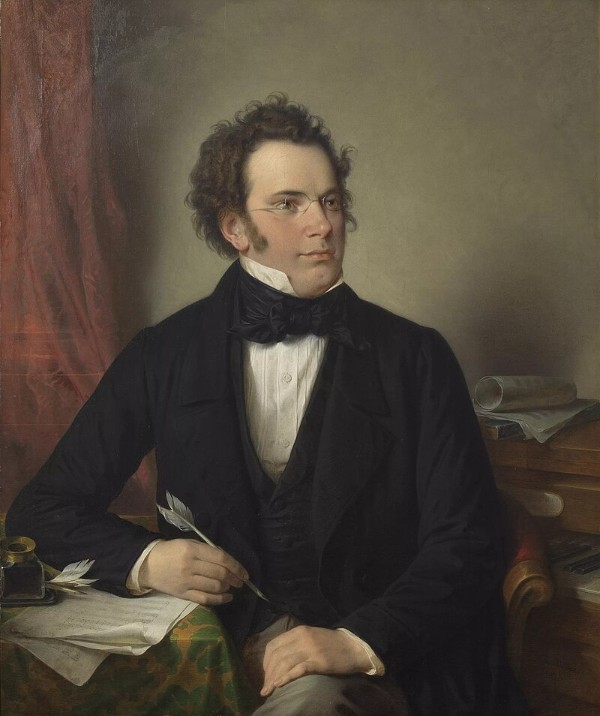

Franz Schubert (1797–1828) picked up the text in 1815 and made it part of his Op. 5 collection, setting it in a precise and concise manner, and reserving his emotion for the last word of the 2nd stanza, ‘Wunde’ (wound). The minor-key setting is full of wistful memory and desire.

Wilhelm August Reider: Franz Schubert, 1875 after a 1825 watercolour (Vienna Museum)

Bohemian composer Václav Jan Křtitel Tomášek (1774–1850) led the musical world of Prague in the first half of the 19th century. He was the central point of the Mozart cult in Prague, and his fame spread through his lieder and piano compositions. Of his 63 lieder, 41 are settings of Goethe, and Goethe made a point of telling Tomášek in 1822 how much he approved of Tomášek’s work.

Tomášek met the 73-year-old poet in the Bohemian town now called Cheb, and after discussing music, poetry and minerals (Goethe had a famous rock collection), the poet encouraged the composer to play for him. Goethe gave him a book of poetry, and the 48-year-old composer played his music from memory. It was after Mignon’s Sehnsucht that the poet exclaimed, ‘you have understood the poem’, and then went on to say that he could not ‘understand how both Beethoven and Spohr could so entirely misinterpret it and treat it as though it were an aria and not a Lied.’

Tomášek’s setting is full of simple declarations, less full of melancholic regret than we find in other settings. There is still the emphasis on ‘Wunde’, but the setting of the first work of the first and last stanza’s first word, ‘Ach’ (Ah), that seems to carry the sharp despair.

Antonín Machek: Portrait of the Composer V. J. Tomášek, after 1816 (Prague: National Gallery)

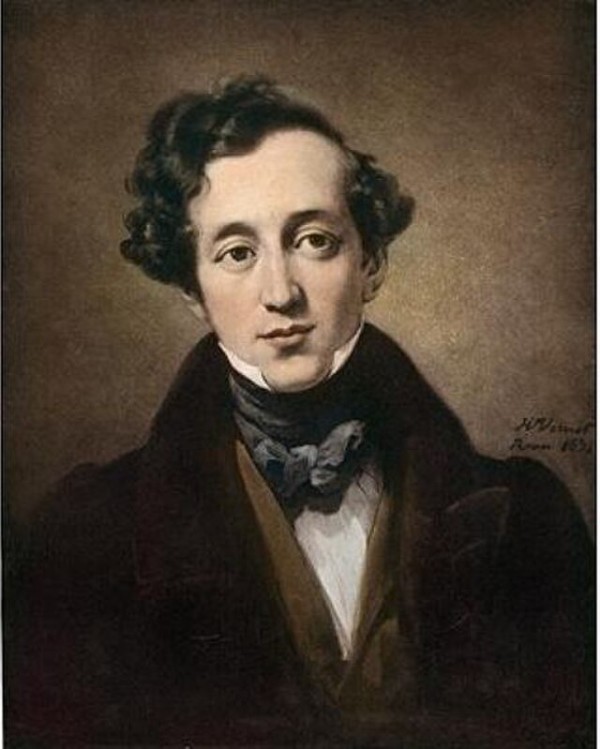

Felix Mendelssohn’s setting in 1841, as part of his Op. 99 collection Sechs Gesänge, expands the setting enormously, setting the same lines multiple times. The impression of the setting is somehow of deeper regret. The contrasting music for the second verse again puts emphasis on the word ‘wound’. The song concludes with decoration on the word ‘holde’ (lovely), bringing the beloved back one more time.

Horace Vernet: Felix Mendelssohn, 1831

Austrian composer Hugo Wolf (1860–1903) set the poem in 1876, as part of his Op. 9 collection, which set the poetry of Lenau, Goethe, and V. Zuzner. Wolf started writing music to the texts of Goethe at age 15, starting with 3 songs for male chorus.

When he set Erster Verlust, he was following the model set for him already by Reichardt, Zelter, Tomášek and Mendelssohn. Although this early setting, created in 1875 when he was just 15, shows much skill, we’re still dealing with the composer’s juvenilia. It is nothing compared to the lieder where he would show his genius.

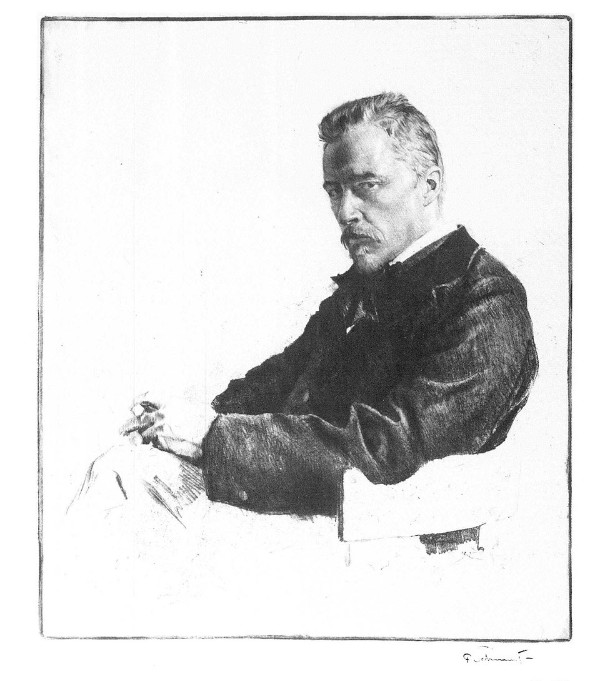

Hugo Wolf

Nicolai Medtner (1879–1951) published his op. 6 collection of 9 Goethe-Lieder between 1901and 1905. The majority of Medtner’s published songs are Russian, but Goethe was one of the most important German poets he set to music. Three of his Goethe collections resulted in him being awarded the Glinka Prize in 1909.

The lied was composed as a wedding present for his brother Emil and his bride Anna; however, the present had more than good wishes behind it. Nicolai had been forbidden marriage with Anna, and so his older brother Emil took his place; the marriage was never consummated. Eventually, Emil and Anna divorced, and then Nicolai and Anna were free to marry.

As a collection, it must be regarded as a wedding gift not to his brother but to his sweetheart, and a text such as Erster Verlust becomes particularly poignant. However, since his first lost love would eventually become his wife, this is one time when the story has a happy ending.

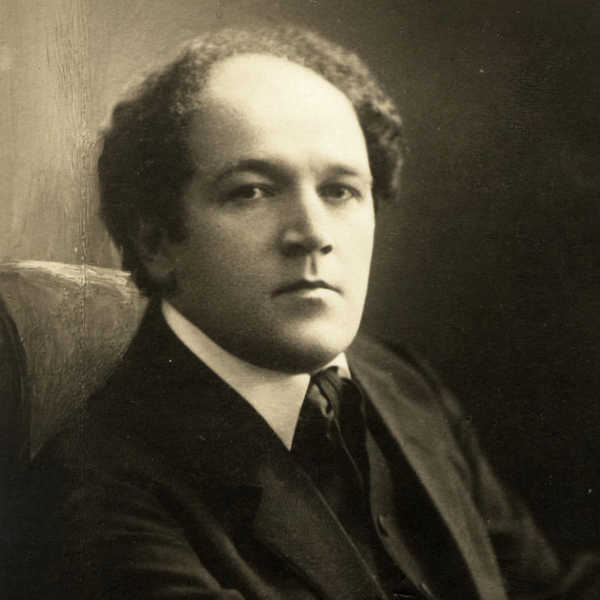

Nicolai Medtner

In his setting, Alban Berg (1885–1935) cuts off the last couplet of the poem, setting only the first two stanzas. The work was written in 1905 when he was just beginning as a composer. He worked with Arnold Schoenberg between 1904 and 1911 and was able to combine Schoenberg’s 12-tone technique with his own late-Romantic lyricism. He started with Schoenberg studying harmony, counterpoint, and music theory, and then, from 1907, composition. Even before studying with Schoenberg, he was a prolific composer, with some 80 lieder to his name. Schoenberg thought he was stuck in song, and over the years of study, made him work on his instrumental compositions.

Of all the Second Viennese School composers, he’s the one who has remained the most listenable. His operas remain in the repertoire.

The simplicity of this early song compared to what we know of his later works gives us true indication of what he learned from Schoenberg. Erster verlust was one of only three songs Berg wrote to a Goethe text, as he gradually started working with texts by more modern poets.

Alban Berg

Justus Hermann Wetzel (1879–1973) set Goethe’s text in 1919, as part of his Op. 3 Liederkreis collection. Over his long life, Wetzel composed over 600 songs of which fewer than 150 are still in the repertoire.

His style of clear melodic lines matched with an intense mood makes this song sound less like 1919 and more like 1819.

Erick Büttner: Justus Hermann Wetzel, 1930 (Berlin: Neue Natioanalgalerie)

Tracking the setting of this song for a century reveals an enormous amount about what composers read into the text and how tastes in lied writing circle around. Goethe’s insistence on the primacy of the text (as befitted him as the poet) could be seen as standing in the way of the composer’s need to create interpretations and filter for the material. Probably one of the most effective settings is Medtner’s, truly written for a lost love and given to the woman herself.

A composer takes his text and then decides what to emphasise (‘wunde’ or ‘Ach’) and how to place that emphasis. Realisation of the meaning of the text can happen in many ways. Not every composer wrote in a minor key, and not every composer read the poem the same way. A survey such as this gives us a deeper appreciation for the way certain composers (including Schubert) were able to find their way through such a seriously emotional path.

What Was It Like Being Liszt’s Student?

by Emily E. Hogstad

She studied at the New England Conservatory of Music in the 1860s and, in 1869, took the daring transoceanic journey to further her studies in Germany.

While in Europe, she studied with Liszt’s student Carl Tausig, as well as Liszt himself.

Her letters to her sister served as the foundation for her book Music Study in Germany, which was published in 1880, and offers a tantalising glimpse into what it was like to be around Liszt in the 1870s.

Today, we’re looking at some of the best stories from Fay’s book.

Amy Fay

Liszt could flirt and watch a play simultaneously.

Last night I arrived in Weimar, and this evening I have been to the theatre, which is very cheap here, and the first person I saw, sitting in a box opposite, was Liszt, from whom, as you know, I am bent on getting lessons, though it will be a difficult thing I fear, as I am told that Weimar is overcrowded with people who are on the same errand.

I recognised Liszt from his portrait, and it entertained and interested me very much to observe him.

He was making himself agreeable to three ladies, one of whom was very pretty.

He sat with his back to the stage, not paying the least attention, apparently, to the play, for he kept talking all the while himself, and yet no point of it escaped him, as I could tell by his expression and gestures.

Liszt was “the most striking-looking man imaginable.”

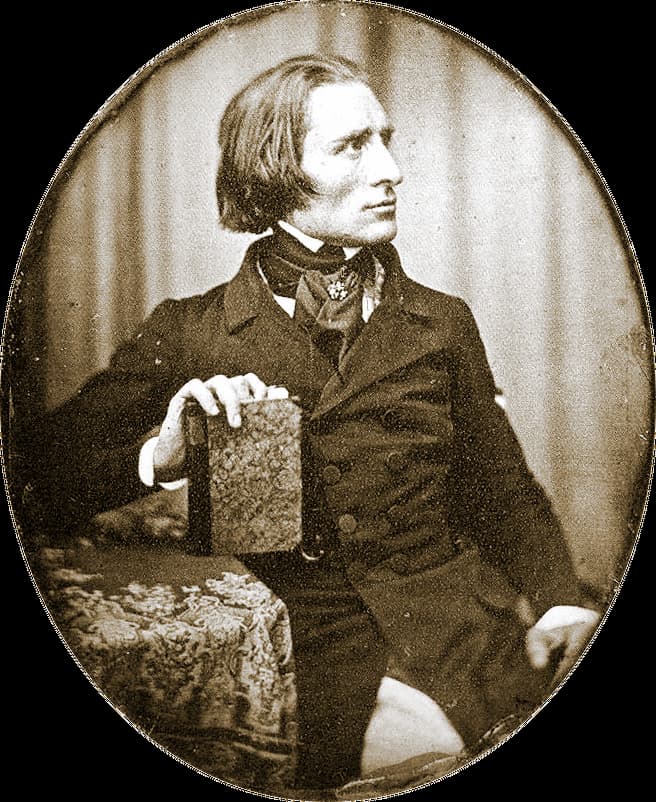

Hermann Biow: Franz Liszt, 1943

Liszt is the most interesting and striking-looking man imaginable.

Tall and slight, with deep-set eyes, shaggy eyebrows, and long iron-grey hair, which he wears parted in the middle.

His mouth turns up at the corners, which gives him a most crafty and Mephistophelean expression when he smiles, and his whole appearance and manner have a sort of Jesuitical elegance and ease.

His hands are very narrow, with long and slender fingers that look as if they had twice as many joints as other people’s. They are so flexible and supple that it makes you nervous to look at them.

Anything like the polish of his manner, I never saw. When he got up to leave the box, for instance, after his adieux to the ladies, he laid his hand on his heart and made his final bow,—not with affectation, or in mere gallantry, but with a quiet courtliness which made you feel that no other way of bowing to a lady was right or proper. It was most characteristic.

Liszt didn’t actually think of himself as a teacher.

Sophie Menter

He asked me if I had been to Sophie Menter’s concert in Berlin the other day.

I said yes. He remarked that Miss Menter was a great favourite of his…

I asked him if Sophie Menter was a pupil of his. He said no, he could not take the credit of her artistic success to himself.

I heard afterwards that he really had done ever so much for her, but he won’t have it said that he teaches!

Later, Fay writes:

He says “people fly in his face by dozens,” and seems to think he is “only there to give lessons.”

He gives no paid lessons whatever, as he is much too grand for that, but if one has talent enough, or pleases him, he lets one come to him and play to him.

Liszt inspired and encouraged his pupils to develop their own artistic identities.

Nothing could exceed Liszt’s amiability, or the trouble he gave himself, and instead of frightening me, he inspired me. Never was there such a delightful teacher! and he is the first sympathetic one I’ve had.

You feel so free with him, and he develops the very spirit of music in you. He doesn’t keep nagging at you all the time, but he leaves you your own conception.

Now and then, he will make a criticism, or play a passage, and with a few words give you enough to think of all the rest of your life.

There is a delicate point to everything he says, as subtle as he is himself. He doesn’t tell you anything about the technique. You must work this out for yourself.

When I had finished the first movement of the sonata, Liszt, as he always does, said “Bravo!”

Liszt was a difficult artist to turn pages for because he sight-read so quickly.

He made me come and turn the leaves. Gracious! how he does read!

It is very difficult to turn for him, for he reads ever so far ahead of what he is playing, and takes in fully five bars at a glance, so you have to guess about where you think he would like to have the page over.

Once I turned it too late, and once too early, and he snatched it out of my hand and whirled it back.

We know exactly what Liszt’s quarters in Weimar looked like.

It is so delicious in that room of his! It was all furnished and put in order for him by the Grand Duchess herself.

The walls are pale grey, with a gilded border running round the room, or rather two rooms, which are divided, but not separated, by crimson curtains.

The furniture is crimson, and everything is so comfortable—such a contrast to German bareness and stiffness generally.

A splendid grand piano stands in one window (he receives a new one every year). The other window is always wide open and looks out on the park.

There is a dove-cote just opposite the window, and the doves promenade up and down on the roof of it, and fly about, and sometimes whirr down on the sill itself. That pleases Liszt.

His writing table is beautifully fitted up with things that all match. Everything is in bronze – ink-stand, paper-weight, match-box, etc., and there is always a lighted candle standing on it by which he and the gentlemen can light their cigars.

There is a carpet on the floor, a rarity in Germany, and Liszt generally walks about, and smokes, and mutters (he can never be said to talk), and calls upon one or other of us to play.

Liszt was fully aware of how his charisma affected his audiences.

Liszt knows well the influence he has on people, for he always fixes his eyes on some of us when he plays, and I believe he tries to wring our hearts.

When he plays a passage and goes pearling down the keyboard, he often looks over at me and smiles to see whether I am appreciating it.

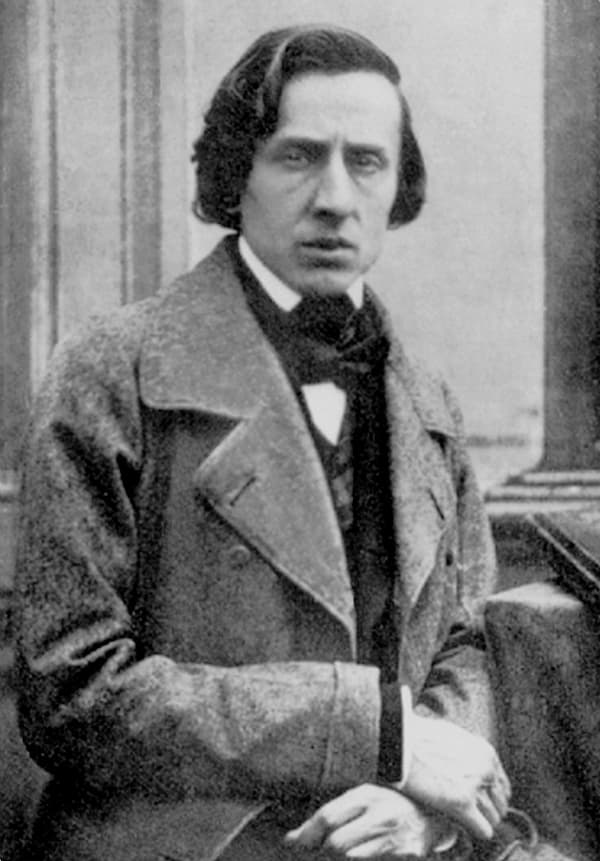

Liszt enjoyed telling people about the time that Chopin put on a wig to impersonate him.

Frédéric Chopin

It was the first time I ever heard Liszt really talk, for he contents himself mostly with making little jests. He is full of esprit.

We were speaking of the faculty of mimicry, and he told me such a funny little anecdote about Chopin.

He said that when he and Chopin were young together, somebody told him that Chopin had a remarkable talent for mimicry, and so he said to Chopin, “Come round to my rooms this evening and show off this talent of yours.”

So Chopin came. He had purchased a blonde wig (“I was very blonde at that time,” said Liszt), which he put on, and got himself up in one of Liszt’s suits.

Presently an acquaintance of Liszt’s came in, Chopin went to meet him instead of Liszt, and took off his voice and manner so perfectly, that the man actually mistook him for Liszt, and made an appointment with him for the next day—”and there I was in the room,” said Liszt. Wasn’t that remarkable?

Liszt actually played wrong notes, but he enjoyed doing so, and knew how to get out of them.

Liszt sometimes strikes wrong notes when he plays, but it does not trouble him in the least. On the contrary, he rather enjoys it.

He reminds me of one of the cabinet ministers in Berlin, of whom it is said that he has an amazing talent for making blunders, but a still more amazing one for getting out of them and covering them up.

Of Liszt the first part of this is not true, for if he strikes a wrong note it is simply because he chooses to be careless. But the last part of it applies to him eminently.

It always amuses him instead of disconcerting him when he comes down squarely wrong, as it affords him an opportunity of displaying his ingenuity and giving things such a turn that the false note will appear simply a key leading to new and unexpected beauties.

An accident of this kind happened to him in one of the Sunday matinees, when the room was full of distinguished people and of his pupils. He was rolling up the piano in arpeggios in a very grand manner indeed, when he struck a semi-tone short of the high note upon which he had intended to end.

I caught my breath and wondered whether he was going to leave us like that, in mid-air, as it were, and the harmony unresolved, or whether he would be reduced to the humiliation of correcting himself like ordinary mortals, and taking the right chord.

A half smile came over his face, as much as to say—”Don’t fancy that this little thing disturbs me,”—and he instantly went meandering down the piano in harmony with the false note he had struck, and then rolled deliberately up in a second grand sweep, this time striking true.

I never saw a more delicious piece of cleverness. It was so quick-witted and so exactly characteristic of Liszt. Instead of giving you a chance to say, “He has made a mistake,” he forced you to say, “He has shown how to get out of a mistake.”