It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Sunday, August 24, 2025

Mozart: Die Zauberflöte – Ouvertüre ∙ hr-Sinfonieorchester ∙ Tarmo Pelto...

/ hrsinfonieorchester ∙

ARD Mediathek: https://www.ardmediathek.de/hr/sendun... ∙

/ hrsinfonieorchester ∙

ARD Mediathek: https://www.ardmediathek.de/hr/sendun... ∙Mozart Overture Cosi fan tutte - Sinfonia Rotterdam / Conrad van Alphen

Saturday, August 23, 2025

Prokofiev - Dance of Knights from Romeo and Juliet

Friday, August 22, 2025

André Rieu - Ta Pedia Tou Pirea (Τα Παιδιά του Πειραιά)

The 10 Most Exciting Double Concertos

by Hermione Lai

There is an old saying that “two heads are better than one” when it comes to reasoning and perceptual decision-making. That might well be true, but are two soloists in classical music better than one? This seems a tricky question as the word “concerto” can mean both to contend, dispute, and debate, but also “to work together with someone.” And there is lots of musical and interpretive cooperation needed when it comes to the “Double Concerto.” The definition of that genre is straightforward, as it simply reads “a composition for two solo instruments with orchestra.” The kinds of instruments are left to the imagination of the composers, and while we are primarily used to hearing solo concertos these days, double concertos used to be very popular with composers and performers alike.

C.P.E. Bach: Concerto in E-flat Major for Harpsichord and Fortepiano, H. 479

C.P.E. Bach’s Double Concerto

So I decided to write a little blog featuring 10 of the most exciting double concertos in the repertoire. And my starting point is Johann Sebastian Bach’s eldest son Carl Philipp Emanuel. As a keyboard composer, he was a true pioneer, “imitating the cantabile melody of applied music,” and incorporating improvisatory passages of dazzling virtuosity. Just have a listen to his Concerto for Harpsichord and Fortepiano, which dates from 1788.

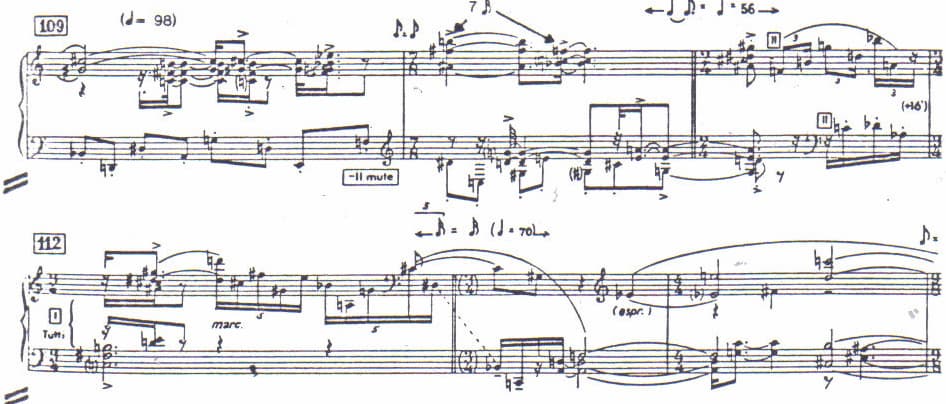

Elliott Carter: Double Concerto for harpsichord, piano and two chamber orchestras

Elliott Carter: Double Concerto for harpsichord, piano and two chamber orchestras

Personally, I think that the C.P.E. Bach Double concerto is a masterpiece, and the same has been said of the double concerto for the same basic setup by American composer Elliott Carter. Mind you, that particular double concerto dates from 1961. And while the musical language is certainly very different, Carter’s double concerto strives for the same delicate balance between the two different keyboard instruments. Of course, the percussion is an added 20th-century bonus. But you don’t have to take my word for it, as Igor Stravinsky regarded the Carter double concerto as a masterpiece. The composer Harrison Birtwistle wrote of the piece, “I love the Double Concerto for piano, harpsichord and two chamber orchestras. There’s nothing like it in music: the concept, the way it makes time and rhythm move, the instrumentation, and that bloody harpsichord!” Pianist Charles Rosen first performed the piano solo part, and he called it “the most brilliantly attractive and apparently most complex work.” And he adds, “The absence of a central pulse adds to the liberating excitement.”

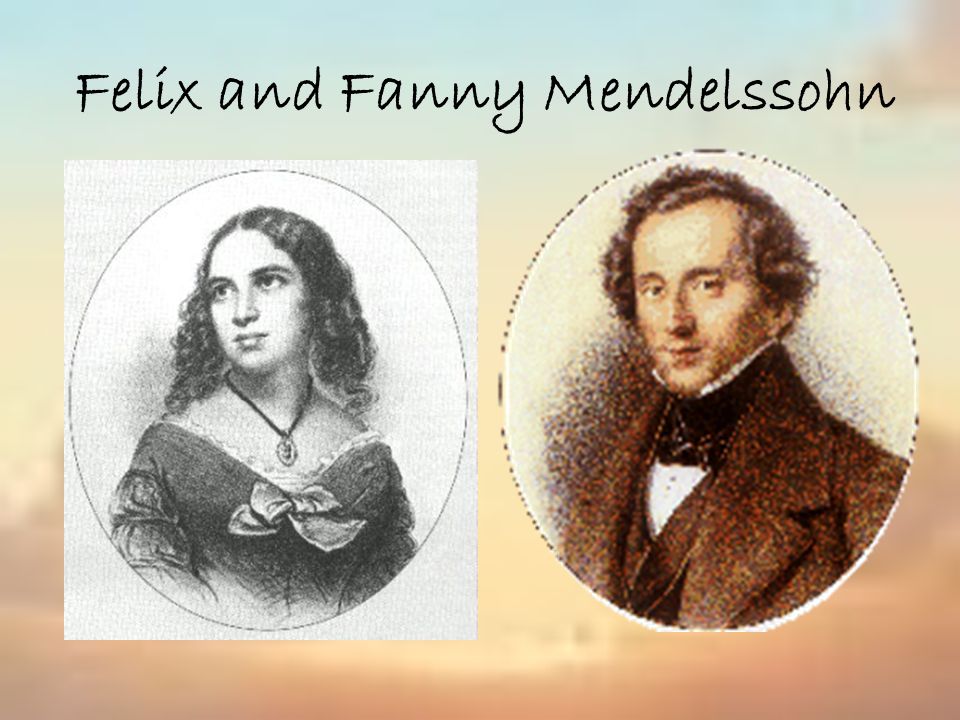

Felix Mendelssohn: Concerto for Two Pianos in E Major

Fanny and Felix Mendelssohn

Lots of double concertos were composed between C.P.E Bach and Elliott Carter, and it’s time to turn to the music of Felix Mendelssohn. He clearly was one of the rare universal geniuses, and by the age of 15 he had already composed 12 string sinfonias, various sonatas for viola and for violin, religious choral pieces, numerous piano compositions, and was busily working on his fourth opera. One of his early compositions is the Concerto for 2 pianos in E Major. It was composed as a birthday gift for his equally talented sister Fanny Mendelssohn. The work unfolds in 3 movements, and the opening “Allegro” starts with an extended orchestral introduction, which could easily have been written by Mozart. After the pianos enter, one at the time, we hear a delightful musical dialogue between two equal partners. But it’s not all Mozart imitation, as we also hear sudden chromatic shifts, surprise cadences, and almost instantaneous shifts in atmosphere—all features we clearly associate with the music of Mendelssohn.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Concerto for 2 pianos in E-flat Major, K. 365

Wolfgang and Nannerl Mozart

You heard me mention Mozart in connection with the Mendelsohn double concerto. Mendelssohn had a ferocious musical mind, and he devoured any and all kinds of music, basically everything he could get his hands on. And that surely included the glorious Concerto for 2 pianos in E-flat Major, K. 365 by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Mozart composed the work in the late 1770s, around the same time as another great double concerto, the Sinfonia Concertante for violin and viola. It has been suggested that Mozart wrote the concerto for two pianos to perform with his sister Nannerl, but there is no record of them playing the work. However, we do know that Mozart performed the work with his student Josepha Auernhammer in Vienna in 1781 and 1782. Mozart was trying to make an impression on the city of Vienna, and he selected this concerto to show some of his best work. It is possible that Mozart enlarged the orchestra, adding clarinets, trumpets, and timpani for these performances, to make an even more brilliant impression. We still don’t know to this day, however, if these orchestral additions are in fact by Mozart or not.

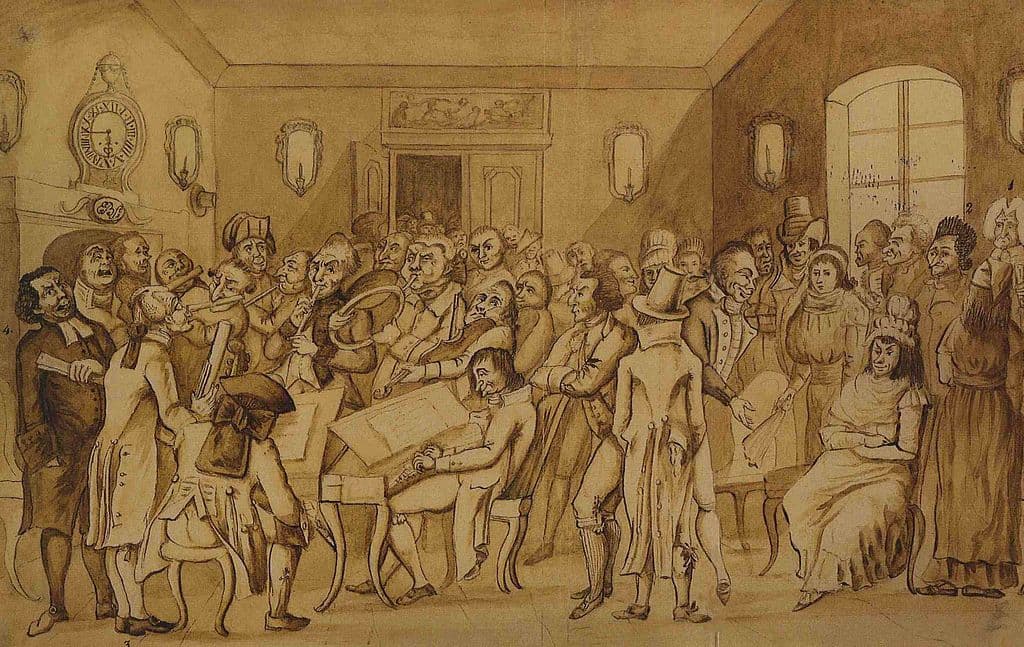

Johann Sebastian Bach: Concerto for two violins in D minor, BWV 1043

Collegium Musicum in Leipzig, 1790

Pianos are fun, but double concertos have been written for other instruments as well. Did you really think that I would not feature my favorite composer of all time, Johann Sebastian Bach? And we are lucky indeed that Bach left us with the Concerto for Two Violins in D minor, BWV 1043, one of the most magnificent double concertos in the repertoire. It really is surprising that a substantial number of Bach’s compositions cannot be dated with certainty. And that is certainly true for many of his concertos, as many are arrangements of previous versions. There is lots of scholarly squabbling going on, and it all depends on which argument you would like to believe. Some say that the work originated during Bach’s tenure at the court of Cöthen between 1717 and 1723. Others have argued that it comes from Bach’s appointment as the director of the Collegium Musicum in Leipzig after 1730. And we also know that Bach himself produced a transposed arrangement of this concerto for two harpsichords in 1739. While we might not be sure of the exact date, we certainly hear a work of remarkably expressive intensity. The themes are full-bodied and highly irregular and presented with Bach’s tremendous and glorious urgency.

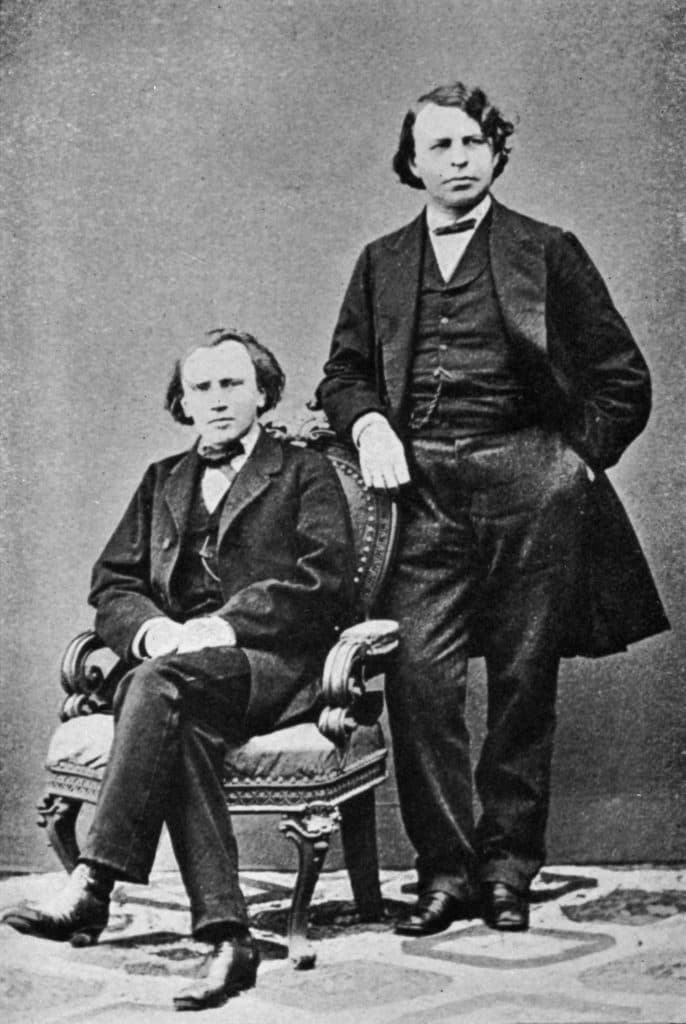

Johannes Brahms: Concerto for Violin, Cello and Orchestra in A minor, Op. 102

Joseph Joachim and Johannes Brahms, 1855

From “B” for Bach, let’s move next to “B” for Brahms. Life works in mysterious ways, and the Brahms Concerto for Violin, Cello and Orchestra in A minor, Op. 102, owes its existence to a divorce, at least partially. One of his best friends, the violinist Joseph Joachim accused his wife Amalie Weiss of infidelity with Brahms’ music publisher. Brahms did not believe Joachim’s accusation, and he wrote a sympathetic letter to Amalie. Unfortunately, when Joachim filed for divorce, that letter ended up as evidence. Brahms had written, “With no thought have I ever acknowledged that your husband might be in the right. At this point, I perhaps hardly need to say that, even earlier than you did, I became aware of the unfortunate character trait with which Joachim so inexcusably tortures himself and others… The simplest matter is so exaggerated, so complicated, that one scarcely knows where to begin with it and how to bring it to an end.” The judge was certainly convinced and quickly ruled in Amalie’s favor. Always professional, Joachim continued to perform and promote the music of Brahms, but the two did not speak again for four long years. In 1887, Brahms remembered that he had promised to write a piece for the cellist Robert Hausmann, and so he decided to kill two birds with one stone by also including Joachim. Without doubt, the friendship was in need of patching up, and Joachim enthusiastically agreed.

Frederick Delius: Concerto for Violin, Cello and Orchestra

Cellists May and Beatrice Harrison, c. 1920s

The idea of featuring a violin and cello soloist in a double concerto also appealed to Frederick Delius (1862-1934). In fact, hearing the sisters May and Beatrice Harrison in a Hallé Orchestra concert performing Brahms’s Double Concerto in 1914, certainly kindled his interest. The Harrison sisters were celebrated figures in British music, and both became closely associated with Delius’ music. Shortly after the Brahms performance, Delius apparently said to Beatrice, “Your performance was superb, so much so that I am inspired to write a double concerto and dedicate it to you and your sister.” The composer frequently consulted the Harrison sisters, and May reports, “When Delius began the Double Concerto at our house in Cornwall Gardens he wrote a lot of it in unison. We both said, ‘you can’t do that, it doesn’t sound right.’ And when we played bits he said, ‘No, you are quite right. I see what you mean.’ Delius used to come over with two pages, sit at the piano and then say, ‘This is what I want.’ He then bring two more pages and so in this way it was built up.” In the end, Delius built his double concerto in 5 undulating and entwined movements.

Joseph Haydn: Double Concerto for Harpsichord, Violin and Strings in F Major

Maria Anna Keller

It is called Haydn’s “only surviving concerto for two solo instruments,” but it was probably originally intended for the organ. I am talking about the Concerto in F Major for Harpsichord, Violin and Strings, Hob.XVIII:6. It appears to have been written for Therese Keller, his future sister-in-law, who decided to become a nun in 1756. However, there is a backstory to this double concerto. Therese Keller was the daughter of a wigmaker, and a student of Haydn. He taught her to play the piano and fell head over heels in love with her. Therese, as it turns out, had been earmarked by her family for religious life, and she eventually did join a nunnery. Haydn, however, was considered a good catch as he was already earning money from the aristocracy and he had recently composed his first symphony. So the Keller family came up with the glorious idea that Therese’s older sister Maria Anna might be a suitable replacement. Haydn wasn’t thrilled and it took him almost five years to settle on a wedding day. That relationship, as we know, was an unmitigated disaster.

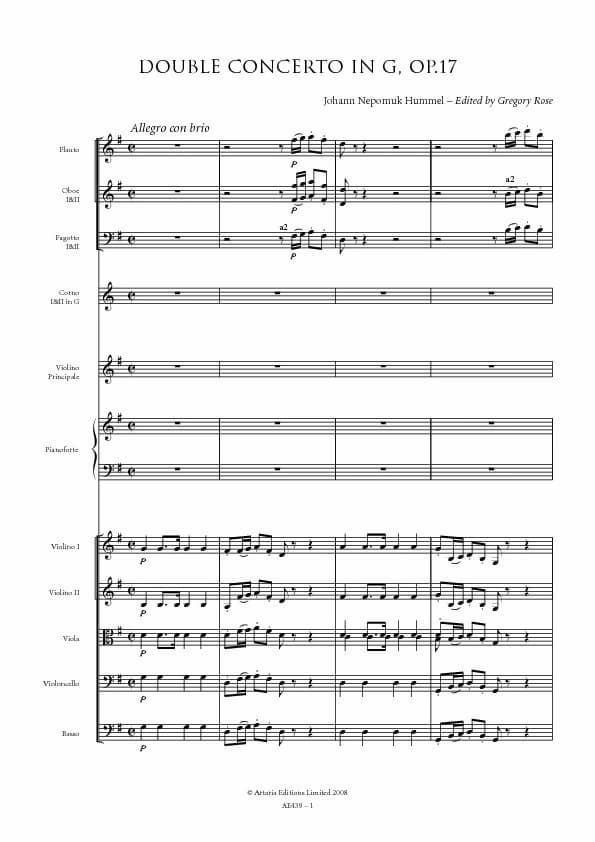

Johann Nepomuk Hummel: Concerto for Violin and Piano in G Major, Op. 17

Johann Nepomuk Hummel: Concerto for Violin and Piano in G Major, Op. 17 © Artaria Editions

The combination of the solo piano and solo violin also held some fascination for Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778-1837). And there is even a closer connection to Haydn himself. Both composers worked for the Esterhazy family in the castle of Eisenstadt. Haydn would stay there for nearly thirty years, while Hummel managed to get himself fired for neglecting his duties after only seven years. Both composers greatly enjoyed the local wine, but Hummel wanted to see the world and eventually became a pianist famous for his technical skills. In fact, only his fellow pianist Ludwig van Beethoven could rival his technical prowess. Hummel’s double concerto dates from 1804, and it is scored in the traditional three concerto movements. Hummel dishes out a delightful interplay between the two solo instruments, maybe slightly less virtuosic than in many solo concertos, but the music flows with consuming ease and beauty. Also noteworthy is the fact that Hummel fully composed his own cadenza for the opening movement. And we can hear an additional Hummel cadenza in the concluding playful Rondo.

Francis Poulenc: Concerto for Two Pianos and Orchestra in D minor

Francis Poulenc: Concerto for Two Pianos and Orchestra in D minor © Sheet Music Plus

With so many great double concertos to choose from, it is very difficult to decide on a good closer. In the end, I decided on a work of childlike exuberance, filled with teasing, innocence, caricature, and the sounds of the Parisian street café. I am talking about the Concerto for Two Pianos by Francis Poulenc. Premiered on 5 September 1932, Poulenc literally found his inspirations around every corner. The opening figuration is thought to have been inspired by Poulenc’s encounter with a Balinese gamelan at the 1931 Exposition Coloniale de Paris. The instrumentation and jazzy effects come from Ravel’s G major Concerto, which premiered in Paris just a couple of months earlier. However, the composer admitted that the opening theme goes all the way back to Mozart because, “I have a veneration for the melodic line and because I prefer Mozart to all other composers.” However, there was one more influence at play. Poulenc wrote in a letter to the Russian-born composer and conductor Igor Markevitch, “Would you like to know what I had on my piano during the two months gestation of the Concerto? The concertos of Mozart, those of Liszt, that of Ravel, and your Partita.” What a fabulous and fun...

The Composer as Poet: Claude Debussy

by Maureen Buja

Claude Debussy © Henri Manuel/Getty Images

We think of Debussy as the composer of the dreamworld sound of impressionism. He was an active follower of the symbolist movement, which rejected naturalism, realism, and clear-cut forms in favour of the indefinite and the mysterious. The symbolist poets tried to put music at the centre of their world. Verlaine and Mallarmé worked towards a ‘musicalization’ of poetry.

In his musical language, Debussy always included the extra-musical structural format of poetry. By reversing the relationship between a composer and his poetry, Debussy’s songs were more fluid and adventuresome, in comparison to his instrumental music, which was more restricted by the necessity for fixed keys.

In 1892, he became a poet himself, starting work on his Proses lyriques, a set of four songs to which he wrote the poetry, under the influence of the symbolist poets. He completed the set in 1893. At the same time, he had just finished Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune (1891-4), the String Quartet (1894), and had started work Pelléas et Mélisande (started 1893, completed 1902).

The title, Proses lyriques, is indicative of the problem that French poets faced. French poetry operated under a set of ‘rules and conventions’ that meant that, read as poetry, the verse would have one set of metrical stresses that would be different when read in an ordinary voice. Composers, faced with this difficulty, that would have been fundamental to their text setting, started to look towards prose for inspiration. We note that Debussy’s major opera, Pelléas et Mélisande, sets a prose text.

Debussy’s abandonment of strict verse forms only lasted until 1902. After the premiere of Pelléas et Mélisande, and with only one exception he returned to verse and abandoned prose texts for the rest of his career.

His setting of the Proses lyriques consists of 4 songs: De rêve (1892), De grève (1892), De fleurs (1893), and De soir (1893). He set another 2 songs as the Proses lyriques, set 2, otherwise known as Nuits blanches (1898): Nuit sans fin and Lorque’elle est entrée. In 1915, he set one more piece of his own poetry: Noël des enfants qui n’ont plus de maisons.

The four poems are full of colour: golden moons, white shivers, gilded leaves (De rêve), white silk, green silk dresses, grey quarrels, white kisses (De grève), green boredom, purple iris, lilies as white jets, black petals of boredom (De fleurs), the blue of my dreams, gold or silver (De soir).

The final song in the set, De soir, is both a commentary on the craziness of a Sunday where everyone heads out to the countryside, the memories of past Sundays, and then finally the night, which comes with velvet steps as the Virgin scatters the flowers of sleep. It’s an extraordinary musing on a weekend day and how it ends.

The 1898 songs, collected under the title of Nuits blanches, are very different in nature: both are tales of disappointed love. The second song, Lorque’elle est entrée (When she first appeared) tells the story of the lover who has fallen out of love and sees his beloved now with different eyes: ‘…deceit was caught in the folds of her skirts; her large eyes glowed with falsehood,’ her sweet words are harsh and wounding in actuality, but nevertheless, when she touches him, he cannot help but feel his desires flare again.

Debussy’s last poem, which he set to music in 1915, is completely different again. It is a Christmas song for a time of war. Noël des enfants qui n’ont plus de maisons (Christmas for children who no longer have houses). It starts with ‘Our houses are gone! The enemy has taken everything, even our beds!’ and leads to the back story of how father went to war, mother has died, and now there are no toys. There’s no daily bread. It closes with: ‘Christmas, listen to us. Our wooden shoes are gone, but grant victory to the children of France!’

No other composers have set these texts – they remain by Debussy for Debussy alone. The problem of French poetry, with its historically strong metres that drove the music, is solved when you move towards prose. Any problems with poets are solved when you’re the poet yourself!

15 Pieces of Classical Music About Mountains

By Emily E. Hogstad

Mountains have intimidated and inspired humanity for centuries…and that goes for composers, too!

Some fabulous classical music has been written over the centuries about mountains, travels up and across mountains, the unique natural phenomena found in mountains, and more.

Get ready: we’re about to climb the mountain of classical music about mountains!

Slovakia’s Tatra Mountains

Johannes Eccard: Übers Gebirg Maria geht (ca. 1600)

German composer Johannes Eccard lived from 1553 to 1611. He became a famous composer during the early days of Protestantism.

“Übers Gebirg Maria geht” translates into “Over the mountains Mary goes.”

This motet tells the story of how Mary, the mother of Jesus, traveled over mountains to find her cousin Elizabeth, whom she wanted to tell about her divinely ordained pregnancy.

The motet is written for five vocal parts (first soprano, second soprano, alto, tenor, and bass).

Franz Schubert: Der Alpenjäger (1817)

The word “Der Alpenjäger” means “The Alpine Hunter” in English.

In this song, Schubert sets a poem by his dear friend Johann Mayrhofer describing the hunter’s hike.

He climbs up into the mist on steep paths, thinking of his beloved, who is still at home. When he mounts the summit, the beams of sunlight remind him of her.

Hector Berlioz: Harold en Italie, Movement 1 “Harold aux montagnes” (1834)

Harold en Italie is an unusual piece. In many ways, it resembles a symphony, but with a twist: there’s a very prominent solo viola part.

Said viola represents the piece’s protagonist, whose name is Harold.

Titles of the work’s four movements suggest a story starring Harold:

1. Harold in the mountains

2. March of the pilgrims

3. Serenade of an Abruzzo mountaineer

4. Orgy of bandits

The mysterious opening movement opens in a melancholy fashion, but soon Harold’s genial good nature is revealed as the music shifts from a soulful adagio to a bouncy, lively allegro.

Franz Liszt: Ce qu’on entend sur la montagne (1848)

“Ce qu’on entend sur la montagne” translates into “What one hears on the mountain.” It’s based on a famous Victor Hugo poem from 1831.

This piece is not quite an overture and not quite a symphony (although it is sometimes referred to as the Bergsymphonie, or Mountain Symphony). It’s probably most accurate to call it a symphonic tone poem.

Liszt himself described the story behind the work:

The poet hears two voices; one immense, splendid, and full of order, raising to the Lord its joyous hymn of praise – the other hollow, full of pain, swollen by weeping, blasphemies, and curses. One spoke of nature, the other of humanity! Both voices struggle near to each other, cross over, and melt into one another, till finally they die away in a state of holiness.

Modest Mussorgsky: Night on Bald Mountain (1867)

Like Liszt, composer Modest Mussorgsky also jumped on the tone poem bandwagon in the mid-nineteenth century.

He originally meant to write an opera that included scenes from a witches’ Sabbath set on the Lysa Hora, also known as Bald Mountain, outside of Kyiv.

Lysa Hora (Bald Mountain), Kyiv © travels.in.ua

Mussorgsky described the scene in his head:

The witches used to gather on this mountain, … gossip, play tricks and await their chief—Satan. On his arrival, they, i.e. the witches, formed a circle round the throne on which he sat, in the form of a kid, and sang his praise. When Satan was worked up into a sufficient passion by the witches’ praises, he gave the command for the sabbath, in which he chose for himself the witches who caught his fancy.

The project went through a variety of guises until it became the classic that we associate today with Halloween and Disney’s Fantasia.

Edvard Grieg: In the Hall of the Mountain King from Peer Gynt Suite No. 1 (1875 )

In 1867, famous Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen wrote a play called Peer Gynt. It wasn’t staged until 1875.

At that first staging, fellow Norwegian Edvard Grieg provided music to go alongside it.

In the Hall of the Mountain King, the protagonist Peer Gynt enters into a dream where he is brought into the headquarters of the troll king.

The description sets the scene: “There is a great crowd of troll courtiers, gnomes and goblins. Dovregubben sits on his throne, with crown and sceptre, surrounded by his children and relatives. Peer Gynt stands before him. There is a tremendous uproar in the hall.”

Grieg intended this excerpt to be satirical: “For The Hall of the Mountain King, I have written something that so reeks of cowpats, ultra-Norwegianism, and ‘to-thyself-be-enough-ness’ that I cannot bear to hear it, though I hope that the irony will make itself felt.”

Joachim Raff: Symphony No. 7, “In the Alps” (1875)

German-Swiss composer Joachim Raff was a prominent composer in Germany during the Romantic Era.

His music is rarely heard today, but it’s still worth listening to, given that he was an important colleague of many composers we know today, like Brahms and Bruckner.

Raff enjoyed attaching descriptive subtitles to his symphonies. His seventh portrays the grandeur of the Alps.

Alps from Garmisch

Raff had a friend and colleague named Hans von Bülow, who had a student named Richard Strauss. Turns out, Strauss also wrote a massive orchestral work inspired by the Alps. Many listeners have pointed out the similarities between these two works. A generation separates the two pieces, and it’s fascinating to hear what elements the works share – and what they don’t!

Vincent d’Indy: Symphony on French Mountain Air (1886)

French composer Vincent d’Indy wrote his Symphony on French Mountain Air in 1886. It’s unique for a symphony in that it contains an important piano part, creating an unusual aural texture.

D’Indy heard the work’s main theme as a folk song while in the mountains of southern France. He then adapted it for orchestra and piano, expanding on it.

Charles Ives: From the Steeples and the Mountains (1901-02)

American composer Charles Ives became famous for his artistic independence and iconoclasm. He was a successful insurance salesman, writing music on the side, and could afford to follow the beat of his own drum, so to speak.

Supposedly, when he was a child, he was taking a hike and heard four different churches’ bells ringing at the same time, all sounding different notes. The experience made a big impression.

Something like that effect is replicated here, with its orchestration for four sets of bells and brass.

He wrote on the score, “From the Steeples—the Bells—then the Rocks on the Mountains begin to shout!”

Arnold Bax: A Mountain Mood (1915)

In 1914, 31-year-old married father Arnold Bax fell in love with a lovely, charming, jaw-droppingly talented piano student named Harriet Cohen, who turned nineteen in December. As you can imagine, their relationship faced its share of difficulties.

Bax nicknamed her Tania, because they and all of their friends gave each other nicknames inspired by trendy Russian ballet.

Their desperate romance continued on and off for nearly forty years. He wrote A Mountain Mood for her and dedicated it to “Tania who plays it perfectly.”

Richard Strauss: An Alpine Symphony (1915)

The scale of Strauss’s Alpine Symphony is staggering. It calls for 125 musicians, lasts nearly an hour, and charts eleven hours in a mountain climber’s day.

Over the course of this day, Strauss portrays all kinds of mountaintop scenes: sunrise, the ascent, a waterfall, a pasture, an overgrown wrong path, a glacier, mists, a massive thunderstorm and tempest, and finally, a descent.

Strauss loved the mountains so much that he built a villa in the Alps, and that passion for them shows through in this piece.

Pavel Haas: String Quartet No. 2 “From the Monkey Mountains” (1925)

Czech composer Pavel Haas was born in 1899. He studied with influential composer Leoš Janáček in the early 1920s.

He had a relatively small output, and, due to his perfectionistic nature, refused to give all of his works opus numbers. “From the Monkey Mountains”, however, was among the lucky ones and was bestowed with the number opus 7.

In it, Haas combines Janáček’s sometimes jagged compositional language with elements of jazz.

If you’re surprised by how good this quartet is and wondering why you’ve never heard of its composer before, it’s because Pavel Haas was killed by the Nazis in Auschwitz. Read more from “5 Composers Who Died in the Holocaust Who You Need to Know”.

Ralph Vaughan Williams: The Lake in the Mountains (1947)

In 1941, actors Leslie Howard and Laurence Olivier appeared in a British wartime propaganda film called 49th Parallel. The movie follows a crew of German U-boat operators who escape to Canada and meet a variety of fates.

Its soundtrack was written by Ralph Vaughan Williams, and the music from that soundtrack is the quiet piano piece The Lake in the Mountains.

Alan Hovhaness: Symphony No. 2, “Mysterious Mountain” (1955)

In 1955 Armenian-American composer Alan Hovhaness was commissioned to write an orchestral work by Leopold Stokowski and the Houston Symphony, with the premiere appearing on television on NBC. Eventually, it was bestowed the title “Symphony No. 2.”

Interestingly, Hovhannes ended up not being a very big fan of the work. He later said:

I remember hearing celestial ballet in my head as I lay down to rest from writing the work. Later, I transcribed what I heard in my sleep. After I wrote it, then heard it again in my sleep, certain versions were wrong. So I corrected it. Now I cannot bear to hear it […] it’s just certain parts move me. I go out of the hall whenever the piece is performed.

Jennifer Higdon: Cold Mountain (2015)

In 1997, author Charles Frazier wrote a novel called Cold Mountain. It tells the story of a soldier in the Confederate Army who deserts during the American Civil War, and his journey to North Carolina to return to his beloved…and the tragic fallout that follows him.

The novel was turned into an Oscar-winning film in 2003.

Cold Mountain movie poster

In 2015, composer Jennifer Higdon wrote an opera based on the book. Higdon was a fitting choice, as she’d spent years in Tennessee as a child. She even helped the librettist “southernize” the libretto, so it would be more faithful to speech patterns found in the Appalachian mountains.

Conclusion

Mountains have not only shaped humans’ physical landscapes. They’ve also clearly shaped cultural and musical landscapes, too.

We hope you’ve enjoyed these fifteen pieces of classical music about mountains! Let us know which one is your favourite.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)