By Emily E. Hogstad

Mountains have intimidated and inspired humanity for centuries…and that goes for composers, too!

Some fabulous classical music has been written over the centuries about mountains, travels up and across mountains, the unique natural phenomena found in mountains, and more.

Get ready: we’re about to climb the mountain of classical music about mountains!

Slovakia’s Tatra Mountains

Johannes Eccard: Übers Gebirg Maria geht (ca. 1600)

German composer Johannes Eccard lived from 1553 to 1611. He became a famous composer during the early days of Protestantism.

“Übers Gebirg Maria geht” translates into “Over the mountains Mary goes.”

This motet tells the story of how Mary, the mother of Jesus, traveled over mountains to find her cousin Elizabeth, whom she wanted to tell about her divinely ordained pregnancy.

The motet is written for five vocal parts (first soprano, second soprano, alto, tenor, and bass).

Franz Schubert: Der Alpenjäger (1817)

The word “Der Alpenjäger” means “The Alpine Hunter” in English.

In this song, Schubert sets a poem by his dear friend Johann Mayrhofer describing the hunter’s hike.

He climbs up into the mist on steep paths, thinking of his beloved, who is still at home. When he mounts the summit, the beams of sunlight remind him of her.

Hector Berlioz: Harold en Italie, Movement 1 “Harold aux montagnes” (1834)

Harold en Italie is an unusual piece. In many ways, it resembles a symphony, but with a twist: there’s a very prominent solo viola part.

Said viola represents the piece’s protagonist, whose name is Harold.

Titles of the work’s four movements suggest a story starring Harold:

1. Harold in the mountains

2. March of the pilgrims

3. Serenade of an Abruzzo mountaineer

4. Orgy of bandits

The mysterious opening movement opens in a melancholy fashion, but soon Harold’s genial good nature is revealed as the music shifts from a soulful adagio to a bouncy, lively allegro.

Franz Liszt: Ce qu’on entend sur la montagne (1848)

“Ce qu’on entend sur la montagne” translates into “What one hears on the mountain.” It’s based on a famous Victor Hugo poem from 1831.

This piece is not quite an overture and not quite a symphony (although it is sometimes referred to as the Bergsymphonie, or Mountain Symphony). It’s probably most accurate to call it a symphonic tone poem.

Liszt himself described the story behind the work:

The poet hears two voices; one immense, splendid, and full of order, raising to the Lord its joyous hymn of praise – the other hollow, full of pain, swollen by weeping, blasphemies, and curses. One spoke of nature, the other of humanity! Both voices struggle near to each other, cross over, and melt into one another, till finally they die away in a state of holiness.

Modest Mussorgsky: Night on Bald Mountain (1867)

Like Liszt, composer Modest Mussorgsky also jumped on the tone poem bandwagon in the mid-nineteenth century.

He originally meant to write an opera that included scenes from a witches’ Sabbath set on the Lysa Hora, also known as Bald Mountain, outside of Kyiv.

Lysa Hora (Bald Mountain), Kyiv © travels.in.ua

Mussorgsky described the scene in his head:

The witches used to gather on this mountain, … gossip, play tricks and await their chief—Satan. On his arrival, they, i.e. the witches, formed a circle round the throne on which he sat, in the form of a kid, and sang his praise. When Satan was worked up into a sufficient passion by the witches’ praises, he gave the command for the sabbath, in which he chose for himself the witches who caught his fancy.

The project went through a variety of guises until it became the classic that we associate today with Halloween and Disney’s Fantasia.

Edvard Grieg: In the Hall of the Mountain King from Peer Gynt Suite No. 1 (1875 )

In 1867, famous Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen wrote a play called Peer Gynt. It wasn’t staged until 1875.

At that first staging, fellow Norwegian Edvard Grieg provided music to go alongside it.

In the Hall of the Mountain King, the protagonist Peer Gynt enters into a dream where he is brought into the headquarters of the troll king.

The description sets the scene: “There is a great crowd of troll courtiers, gnomes and goblins. Dovregubben sits on his throne, with crown and sceptre, surrounded by his children and relatives. Peer Gynt stands before him. There is a tremendous uproar in the hall.”

Grieg intended this excerpt to be satirical: “For The Hall of the Mountain King, I have written something that so reeks of cowpats, ultra-Norwegianism, and ‘to-thyself-be-enough-ness’ that I cannot bear to hear it, though I hope that the irony will make itself felt.”

Joachim Raff: Symphony No. 7, “In the Alps” (1875)

German-Swiss composer Joachim Raff was a prominent composer in Germany during the Romantic Era.

His music is rarely heard today, but it’s still worth listening to, given that he was an important colleague of many composers we know today, like Brahms and Bruckner.

Raff enjoyed attaching descriptive subtitles to his symphonies. His seventh portrays the grandeur of the Alps.

Alps from Garmisch

Raff had a friend and colleague named Hans von Bülow, who had a student named Richard Strauss. Turns out, Strauss also wrote a massive orchestral work inspired by the Alps. Many listeners have pointed out the similarities between these two works. A generation separates the two pieces, and it’s fascinating to hear what elements the works share – and what they don’t!

Vincent d’Indy: Symphony on French Mountain Air (1886)

French composer Vincent d’Indy wrote his Symphony on French Mountain Air in 1886. It’s unique for a symphony in that it contains an important piano part, creating an unusual aural texture.

D’Indy heard the work’s main theme as a folk song while in the mountains of southern France. He then adapted it for orchestra and piano, expanding on it.

Charles Ives: From the Steeples and the Mountains (1901-02)

American composer Charles Ives became famous for his artistic independence and iconoclasm. He was a successful insurance salesman, writing music on the side, and could afford to follow the beat of his own drum, so to speak.

Supposedly, when he was a child, he was taking a hike and heard four different churches’ bells ringing at the same time, all sounding different notes. The experience made a big impression.

Something like that effect is replicated here, with its orchestration for four sets of bells and brass.

He wrote on the score, “From the Steeples—the Bells—then the Rocks on the Mountains begin to shout!”

Arnold Bax: A Mountain Mood (1915)

In 1914, 31-year-old married father Arnold Bax fell in love with a lovely, charming, jaw-droppingly talented piano student named Harriet Cohen, who turned nineteen in December. As you can imagine, their relationship faced its share of difficulties.

Bax nicknamed her Tania, because they and all of their friends gave each other nicknames inspired by trendy Russian ballet.

Their desperate romance continued on and off for nearly forty years. He wrote A Mountain Mood for her and dedicated it to “Tania who plays it perfectly.”

Richard Strauss: An Alpine Symphony (1915)

The scale of Strauss’s Alpine Symphony is staggering. It calls for 125 musicians, lasts nearly an hour, and charts eleven hours in a mountain climber’s day.

Over the course of this day, Strauss portrays all kinds of mountaintop scenes: sunrise, the ascent, a waterfall, a pasture, an overgrown wrong path, a glacier, mists, a massive thunderstorm and tempest, and finally, a descent.

Strauss loved the mountains so much that he built a villa in the Alps, and that passion for them shows through in this piece.

Pavel Haas: String Quartet No. 2 “From the Monkey Mountains” (1925)

Czech composer Pavel Haas was born in 1899. He studied with influential composer Leoš Janáček in the early 1920s.

He had a relatively small output, and, due to his perfectionistic nature, refused to give all of his works opus numbers. “From the Monkey Mountains”, however, was among the lucky ones and was bestowed with the number opus 7.

In it, Haas combines Janáček’s sometimes jagged compositional language with elements of jazz.

If you’re surprised by how good this quartet is and wondering why you’ve never heard of its composer before, it’s because Pavel Haas was killed by the Nazis in Auschwitz. Read more from “5 Composers Who Died in the Holocaust Who You Need to Know”.

Ralph Vaughan Williams: The Lake in the Mountains (1947)

In 1941, actors Leslie Howard and Laurence Olivier appeared in a British wartime propaganda film called 49th Parallel. The movie follows a crew of German U-boat operators who escape to Canada and meet a variety of fates.

Its soundtrack was written by Ralph Vaughan Williams, and the music from that soundtrack is the quiet piano piece The Lake in the Mountains.

Alan Hovhaness: Symphony No. 2, “Mysterious Mountain” (1955)

In 1955 Armenian-American composer Alan Hovhaness was commissioned to write an orchestral work by Leopold Stokowski and the Houston Symphony, with the premiere appearing on television on NBC. Eventually, it was bestowed the title “Symphony No. 2.”

Interestingly, Hovhannes ended up not being a very big fan of the work. He later said:

I remember hearing celestial ballet in my head as I lay down to rest from writing the work. Later, I transcribed what I heard in my sleep. After I wrote it, then heard it again in my sleep, certain versions were wrong. So I corrected it. Now I cannot bear to hear it […] it’s just certain parts move me. I go out of the hall whenever the piece is performed.

Jennifer Higdon: Cold Mountain (2015)

In 1997, author Charles Frazier wrote a novel called Cold Mountain. It tells the story of a soldier in the Confederate Army who deserts during the American Civil War, and his journey to North Carolina to return to his beloved…and the tragic fallout that follows him.

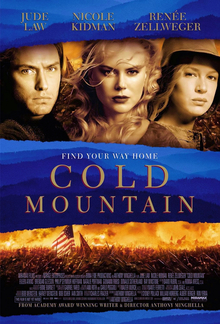

The novel was turned into an Oscar-winning film in 2003.

Cold Mountain movie poster

In 2015, composer Jennifer Higdon wrote an opera based on the book. Higdon was a fitting choice, as she’d spent years in Tennessee as a child. She even helped the librettist “southernize” the libretto, so it would be more faithful to speech patterns found in the Appalachian mountains.

Conclusion

Mountains have not only shaped humans’ physical landscapes. They’ve also clearly shaped cultural and musical landscapes, too.

We hope you’ve enjoyed these fifteen pieces of classical music about mountains! Let us know which one is your favourite.

No comments:

Post a Comment