by Hermione Lai

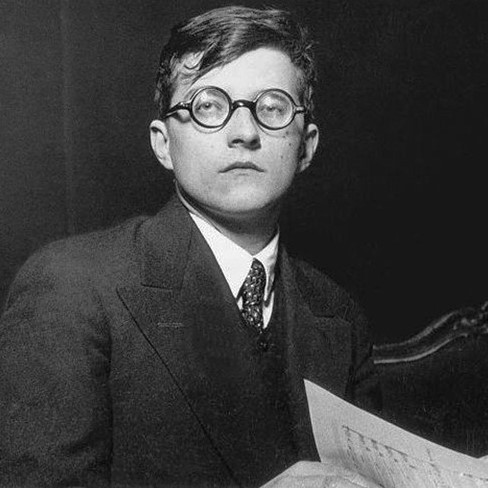

Dmitri Shostakovich

Everything seems full of restless energy with angular melodies interrupted by moments of aching lyricism. Much of it is not just music, but a story that doesn’t quite resolve, and I’m certainly hooked on figuring out what he’s trying to say.

Irony and Hidden Truths

Much of his music strikes a balance between a wiry and percussive drive and ghostly, introspective passages. It’s like he’s painting a picture of an uncertain world, but at the same time clinging to slivers of hope.

I am no virtuoso, but there’s something about his music that makes me want to lean in closer, to uncover the layers of irony and heart he’s tucked away. It’s not always easy listening, but it’s the kind of music that makes you feel like you’re discovering something true.

As we commemorate the 50th anniversary of his death this year, let us explore the world of Shostakovich’s piano music, where every note pulses with raw emotion and hidden stories waiting to be unravelled.

First Piano Sonata

Dmitri Shostakovich

During his days at the Conservatoire, Shostakovich was ranked as a promising concert pianist, and the instrument remained important throughout his career. He wrote some of his most important works for the piano, and he usually played the piano parts of his chamber works and songs at their premiere.

Shostakovich was just 20 years old when he wrote his first Piano Sonata Op. 12. It’s a wild and youthful burst of energy that shows his early genius and his love for pushing boundaries. When his piano professor first heard the work, he commented, “Is this a piano sonata? No, it’s a sonata for metronome with piano accompaniment!”

This bold, single-movement of jagged rhythms, sharp dissonances and sudden mood shifts is terribly difficult to play. And just listen to the aggressive percussive passages with some fleeting lyrical moments. It’s full of avant-garde spirit and virtuosic flair with hints of Prokofiev and even Stravinsky.

Aphorisms

Dmitri Shostakovich

The next piano work of Shostakovich goes off in a completely different direction as he composed a cycle of ten miniatures for piano, eventually titled Aphorisms. Written in Leningrad during his early experimental phase, these miniatures are witty and modern.

Each piece is titled evocatively, including Recitative, Serenade, Nocturne, March, and others, and has a distinct character. It’s like a musical sketch capturing a fleeting mood or idea. A scholar tells us that Shostakovich “subverted the traditional expectations implicit in the title into a ruthless and vinegary application.”

The musical world is turned upside down as we find atonal modernity and a number of caricature-like movements. That Nocturne is not hinting at things that go bump in the night but graphically depicts them. Plenty of sly humour and subtle melancholy and much youthful experimentation, if you ask me.

Dmitry Shostakovich: Aphorisms, Op. 13 (Melvin Chen, piano)

Second Piano Concerto

Dmitri Shostakovich

The piano plays multiple roles in the hands of Shostakovich, and that includes 2 Piano Concertos. Both concertos are relatively short, reflecting his preference for concision and clarity. Above all, they showcase his ability to blend classical forms with modern, often satirical elements.

While the first concerto is a severe, biting, and anguished composition, the Second Piano Concerto, written in 1957, was a birthday present for his son Maxim. As such, it is good-natured, vibrant and sparkles with wit and warmth.

A playful woodwind intro leads to a lively piano melody, and a march-like bugle call shifts to a lyrical theme. The second movement bares raw sadness with a tender piano melody, and the third movement snaps back to a carefree tune. It all ends with a joyful flair, and according to some pianists, “it is one of the most fun concertos to perform in the entire piano repertoire.”

Concertino for 2 Pianos

Shostakovich seriously considered pursuing a career as a concert pianist. However, after only winning a medal of honour at the Warsaw Chopin Competition in 1927, he decided to follow his calling as a composer.

Maxim Shostakovich, the composer’s son, was also a piano prodigy. Shostakovich composed the Concertino for two pianos in 1953 for Maxim as a kind of entrance examination for the Moscow Conservatory.

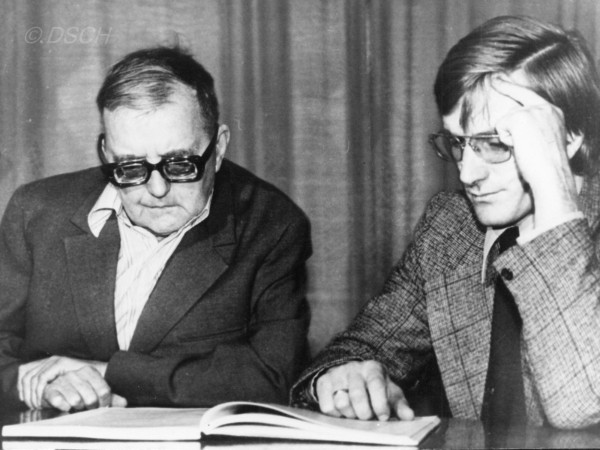

Maxim Shostakovich, 1967

The single-movement work provides plenty of material for young soloists to excel in front of their audience. It is an impassioned work with heavy dotted rhythms and a characteristic forward drive. There is plenty of room for virtuosity and two very attractive themes. One is emphatically melodic and the other march-like. Maxim premiered the piece alongside fellow student Alla Maloletkova in 1954.

Concerto for Piano and Trumpet

Let’s feature one more concerto, specifically the “Concerto for piano and trumpet”, also known as the Piano Concerto No. 1 in C minor. Shostakovich unleashed his piece in the spring of 1933, and ever the musical provocateur, he blended the virtuosic flair of the piano with the brassy interjections of a solo trumpet.

This concerto was composed at the height of Shostakovich’s youthful exuberance. It crackles with a theatrical energy that veers from playful mockery to poignant lyricism. The piano drives the narrative with dazzling runs and biting rhythms, while the trumpet punctuates the dialogue like a wry commentator in moments of jazzy bravado.

This work pulses with Shostakovich’s signature irony, weaving quotations from Beethoven and Haydn into a modernist tapestry that both celebrates and subverts classical traditions. The trumpet part was inspired by the composer’s fascination with popular music and theatre, evoking everything from circus antics to heartfelt speeches.

24 Preludes

In 1932/33, Dmitri Shostakovich poured his restless imagination into the 24 Preludes, Op. 34. It is a cycle of piano miniatures that traverse every major and minor key with a chameleon-like range of emotions.

Each prelude is a fleeting world unto itself. Some sparkle with sardonic wit, others brood with introspective melancholy, while a few erupt in virtuosic bursts of energy. Essentially, Shostakovich weaves a tapestry of contrasts between irony and veiled tragedy.

Shostakovich blends the romantic echoes of Chopin with the sharp edges of modernist dissonance and hints of Russian folk song. These works shimmer with immediacy, delivering emotional punches; the cycle offers a whimsical, haunting, and defiant journey through Shostakovich’s inner landscape

Second Piano Trio

Father and Son Shostakovich

In this little survey of the piano works by Shostakovich, we should also take a quick look at the piano’s role in his chamber music. The work that stands out to me is the Piano Trio No. 2. It was written in the summer of 1944, during a time of mourning for personal and collective losses amidst the horrors of World War II.

This four-movement trio is a tapestry of anguish and resilience, music infused with a raw and almost unbearable emotional weight. The interplay of instruments creates a dialogue that feels like a requiem for a fractured world. Some commentators call it “the composer’s unspoken rage against the brutality of his time.”

Premiered in November 1944 by Shostakovich and members of the Beethoven Quartet, the trio stunned listeners with its emotional directness and technical demands, cementing its place as one of his most profound chamber works. The piano serves as both a driving rhythmic force and a poignant lyrical voice, alternating between sharp intensity and tender introspection.

Second Piano Sonata

Shostakovich’s 2nd Piano Sonata was composed in 1943, and it is also a deeply introspective work. This three-movement sonata also reflects a musical shift from youthful exuberance to a more mature, contemplative voice.

Shostakovich, then in his late 30s, pours his personal and political struggles into the music and creates a soundscape that feels both intimate and universal. The heart of the sonata lies in the second movement, a haunting Largo that unfolds like a quiet lament with the piano weaving hesitant melodies that seem to mourn yet cling to hope.

The final movement drives with relentless energy, featuring intricate counterpoint and syncopated rhythms that culminate in a powerful yet bittersweet close. One needs technical precision and emotional maturity as a pianist to convey the layered complexity. This is one more exploration of Shostakovich’s inner works, simultaneously raw, reflective, and profoundly moving.

For Shostakovich, the piano becomes a most versatile and expressive voice. The instrument carries his signature blend of intensity, irony, and introspection across genres. The piano in Shostakovich’s hands, conveying personal struggle, subtle humour, or profound resilience, is one of the most intensely emotional storytellers in music.

No comments:

Post a Comment