by Frances Wilson, Interlude

Practical Tips for Amateur Pianist

© 4.bp.blogspot.com

Alan Rusbridger’s book ‘Play It Again’ (published in 2013) shone a delightful and inspirational light on the world of amateur pianism, but people have been playing music at home and with friends for almost as long as keyboard instruments have been in existence. In the nineteenth century, when advances in design and production significantly reduced the cost of manufacturing pianos, an upright piano in the parlour was the norm for family entertainment, much as the PlayStation or smart TV is today (sadly).

Probably the single most positive aspect of being an amateur pianist is not having to make a living from playing the instrument. Recently, I have begun to play for solo performances and accompanying, which puts me in the hallowed category of “professional pianist”, but my main income comes from piano teaching, and I wouldn’t have it any different, to be honest. Not having to earn a living from playing the piano means one can truly indulge one’s passion for it. (Indeed, the word “amateur” comes from the Old French meaning “lover of” from the Latin amator.) All the amateur pianists I meet and know play the piano because they love it and care passionately about it.

© photos1.meetupstatic.com

That is not to say that professionals don’t love the piano too – of course they do, otherwise they wouldn’t do it, but a number of concert pianists whom I’ve met and interviewed have expressed frustration at the demands of the profession – producing programms to order, the travelling, the expectations of audiences, promoters, agents etc, all of which can obscure the love for the piano and its literature. Because of this, professionals are often quite envious of the freedom amateur pianists have to indulge their passion, to play whatever repertoire they choose and to play purely for pleasure.

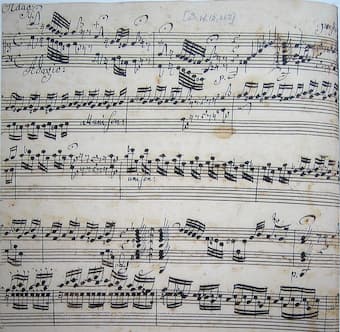

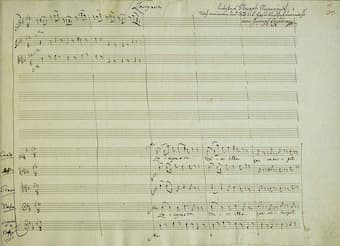

Lucky pianists: the piano has a vast repertoire, more than enough to suit all tastes. One could spend a lifetime learning and playing only the music of, say, J.S. Bach or Frédéric Chopin and only scratch the tiniest surface of the piano repertoire. And in addition to solo works, there is music for three, four, six hands to enjoy with other pianists, not to mention being called upon to accompany other instrumentalists and singers… Really, we are spoilt rotten!

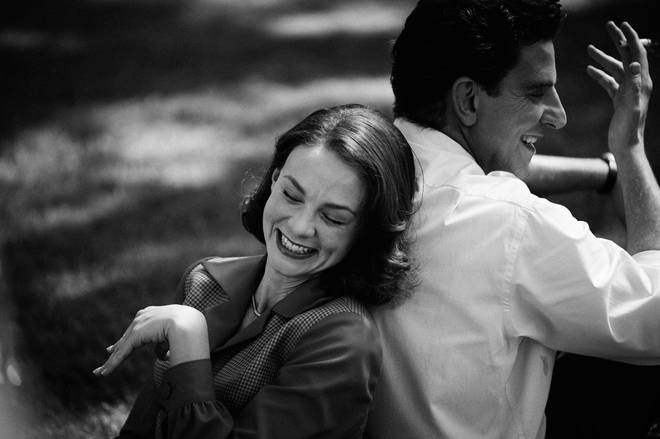

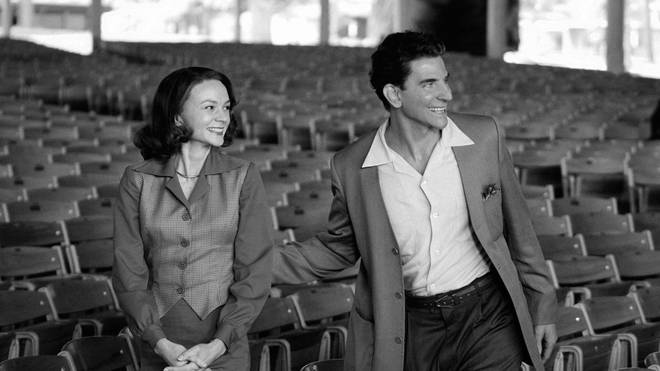

Being a pianist can be a lonely occupation/hobby and working alone on that knotty section of Liszt or Hanon exercises can at times be frustrating and demoralising. However, it needn’t be lonely: in recent years the popularity of piano meetup groups and piano clubs, or even informal get-togethers at one another’s houses, has created a wonderful community of like-minded people who meet regularly to play for one another, share repertoire and socialise.

© 1901artsclub.com

Some adult amateur pianists are shy about playing to others for fear of making mistakes and looking foolish, or because of negative experiences in childhood piano lessons. Piano meetups and clubs are a good way of overcoming these anxieties – you quickly discover that most people feel the same and playing to a friendly non-judgmental group of people is an excellent way of overcoming those performance nerves.

Adult pianists may also find it difficult to find the right teacher to support and encourage them. Some adults like to be pushed by a teacher, others need more gentle handling. Many come to lessons with a lot of “baggage” and anxieties, often a hangover from childhood music lessons, and need encouragement and support. Some have rather over-ambitious ideas about their capabilities and want to play repertoire which is just too challenging. In such instances, I recommend selecting repertoire that is well within one’s “comfort zone” to give one confidence, while gradually introducing more complex repertoire to extend and challenge one’s abilities, both technical and musical. And no repertoire should ever be considered “off limits” to the amateur pianist: the music was written to be played!

However, the music still has to be learnt and one of the greatest frustrations expressed by amateur pianists is finding the time to practise, especially if you have a busy day job and/or family commitments. We all know that “practise makes perfect”, but what is more important is that practise makes permanent and regular practise means notes are learnt, finessed and made secure. My personal mantra is “little and often” and I have become adept at sneaking practise sessions into a particularly busy day or if I am going to be away from the piano for a period of time. It’s amazing what just 10 minutes focused practising can achieve – but you need to know what needs to be done (a good teacher will offer guidance on this and give one tools to practise efficiently and effectively).

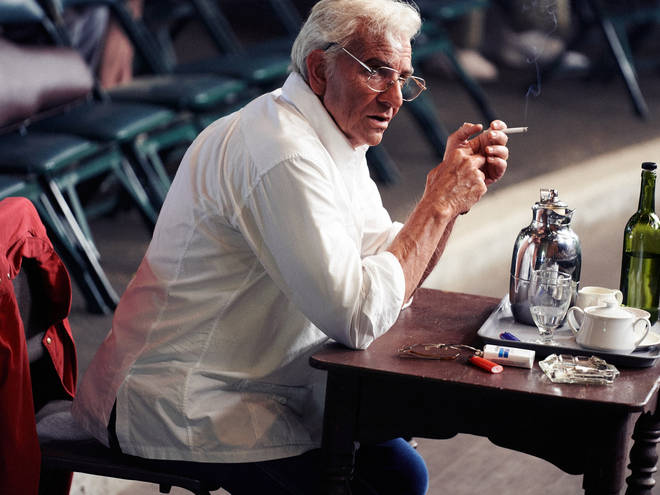

If you don’t have the benefit of regular lessons with a teacher, there are plenty of online resources in the form of blogs, YouTube tutorials, and forums, and there are also courses for adult amateur pianists where you can study with international concert pianists and acclaimed teachers or simply enjoy being amongst like-minded people. Such courses are a great way to meet other pianists and observing others being taught in the masterclass or group workshop setting can be really useful. Many of my pianist friends return to the same courses year after year and firm friendships have been forged.

Not everyone has the luxury of an acoustic piano (upright or grand) but there are some excellent digital pianos on the market now. There are also street pianos in public spaces, railway stations and airports just begging to be played, and if you crave the sleek elegance of a grand piano, there are rehearsal rooms available to hire for a modest fee. Seated at that glorious, gleaming black expanse of mahogany, you can set your imagination free and dream of playing to a full house at the Wigmore or Carnegie Hall.

Eventually Rodrigo was awarded the “Conde de Cartagena Scholarhip” allowing him to join his wife in Paris. Victoria gave up her career as a pianist to devote all her efforts to the works of her husband, collaborating with him in musical and literary matters. When the scholarship was initially renewed, the couple decided to spend some time in Germany. However, with the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, the scholarship fund was no longer available and they had to find refuge at the Institute for the Blind in Freiburg. Three years of extended hardship finally came to an end in 1939, and Rodrigo completed his most famous composition, the Conceirto de Aranjuez. Victoria writes that shorty after the premiere of the concerto on 9 November 1940, their daughter Cecilia was born. “And what about her eyes?” Victoria asked weakly. “They’re magnificent, blue.”

Eventually Rodrigo was awarded the “Conde de Cartagena Scholarhip” allowing him to join his wife in Paris. Victoria gave up her career as a pianist to devote all her efforts to the works of her husband, collaborating with him in musical and literary matters. When the scholarship was initially renewed, the couple decided to spend some time in Germany. However, with the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, the scholarship fund was no longer available and they had to find refuge at the Institute for the Blind in Freiburg. Three years of extended hardship finally came to an end in 1939, and Rodrigo completed his most famous composition, the Conceirto de Aranjuez. Victoria writes that shorty after the premiere of the concerto on 9 November 1940, their daughter Cecilia was born. “And what about her eyes?” Victoria asked weakly. “They’re magnificent, blue.”