by Maureen Buja

| Erster Verlust | First Loss |

| Ach wer bringt die schönen Tage, | Ah, who can bring back the beautiful days, |

| Jene Tage der ersten Liebe, | Those days of first love, |

| Ach wer bringt nur eine Stunde | Ah, who can bring back even one hour |

| Jener holden Zeit zurück! | Of that lovely time! |

| Einsam nähr’ ich meine Wunde | Lonely, I nurse my wound |

| Und mit stets erneuter Klage | And with ever-renewed lament |

| Traur’ ich um’s verlorne Glück. | I mourn for lost happiness. |

| Ach, wer bringt die schönen Tage, | Ah, who can bring back the beautiful days, |

| Jene holde Zeit zurück! | That lovely time! |

Joseph Karl Stieler: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe at age 79, 1828 (Neue Pinakothek)

Johann von Goethe (1749–1832)’s poem entitled ‘Erster Verlust’ (First loss) was first written in 1785 for his Singspiel Die ungleichen Hausgenossen (The Unequal Housemates), intended to be an aria for the Baroness, in Act II. The play was never completed, sidetracked, perhaps, by Goethe’s plans for his upcoming Italy trip. Luckily, he salvaged the poem (and two others) and included them in his Schriften of 1789. For the Schriften printing, Goethe wrote stanzas 2 and 3 anew.

Because of its small size and simple expression, the poems became a favourite of many composers, with some 50 setting it to music. We will look at the song and its setting over the century from 1813 through 1919. In this 8-line poem, Goethe expresses that painful memory of what was lost when one’s first love is no longer your love. There’s no idea of death, but rather hints of decisions made, time lost, and a mourning for the past.

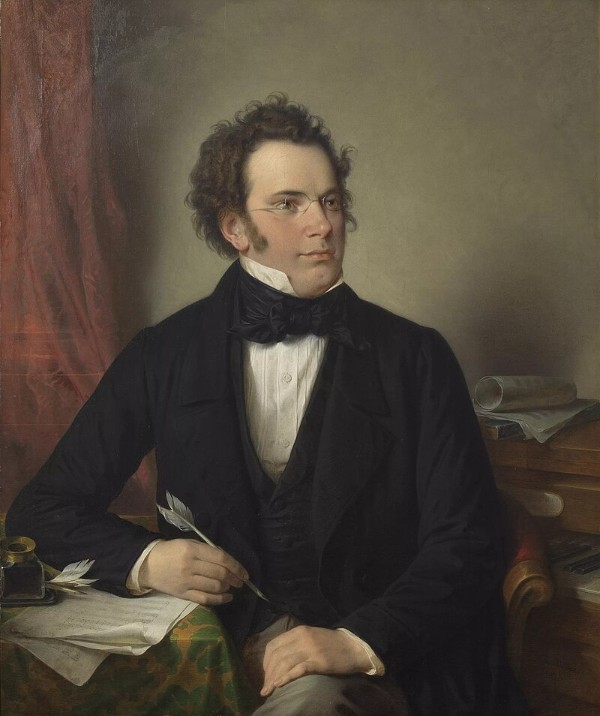

Carl Friedrich Zelter (1758–1832) was one of Goethe’s favourite composers and became the poet’s musical advisor. He was a detailed chronicler of musical events of his time, and his letters are a prime source of information about significant events, such as the famed 1812 meeting of Beethoven and Goethe. Organised by Bettina Brentano, the two men met in the Bohemian spa town of Teplitz. As expected, they did not agree with each other’s self-assessment: Beethoven thought the poet too loving of the court atmosphere, and Goethe thought the composer had ‘an absolutely uncontrolled personality’. Goethe was 63 years old and Beethoven a mere 42.

Zelter wrote over 200 lieder, 75 of them to texts by Goethe. He detailed his thoughts on lieder writing in a letter to the composer Carl Loewe: the text must take priority, the strophic song is to be preferred to ‘absolute through-composing’, and the accompaniment must stay in the background.

Goethe, for his part, had his musical demands, the primary of which was that the music should support the poet’s words. This led Zelter to write music that was plain and strophic, even when the textual manner was more emotional. The music serves the poet’s words, and we can understand why Goethe was so taken with him. Famously, Goethe preferred Zelter’s setting of the poem Erlkönig, rather than the more dramatic setting by Schubert that is so well known today.

The song was published in 1813 as part of Zelter’s collection of 48 sämmtliche Lieder, Balladen und Romanzen; the four-volume collection was in its second edition by 1816.

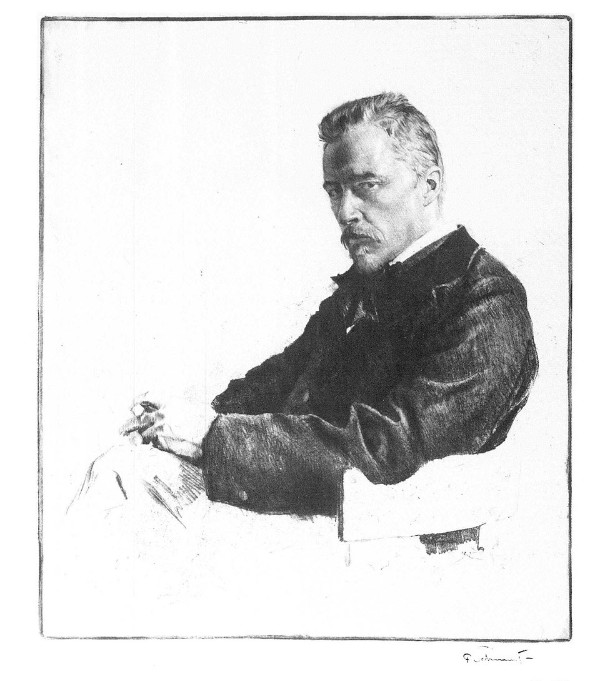

Carl Begas: Carl Friedrich Zelter, 1827 (Sing-Akademie zu Berlin)

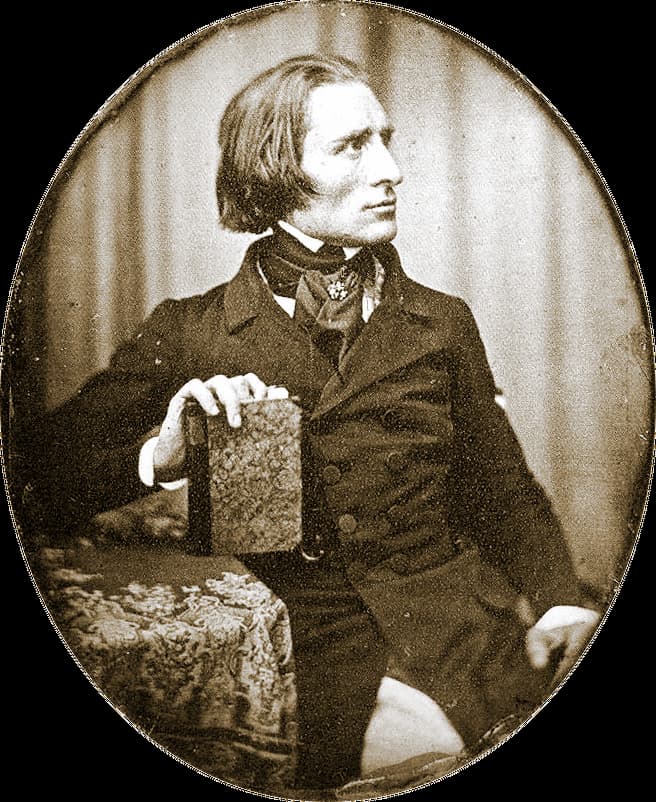

Franz Schubert (1797–1828) picked up the text in 1815 and made it part of his Op. 5 collection, setting it in a precise and concise manner, and reserving his emotion for the last word of the 2nd stanza, ‘Wunde’ (wound). The minor-key setting is full of wistful memory and desire.

Wilhelm August Reider: Franz Schubert, 1875 after a 1825 watercolour (Vienna Museum)

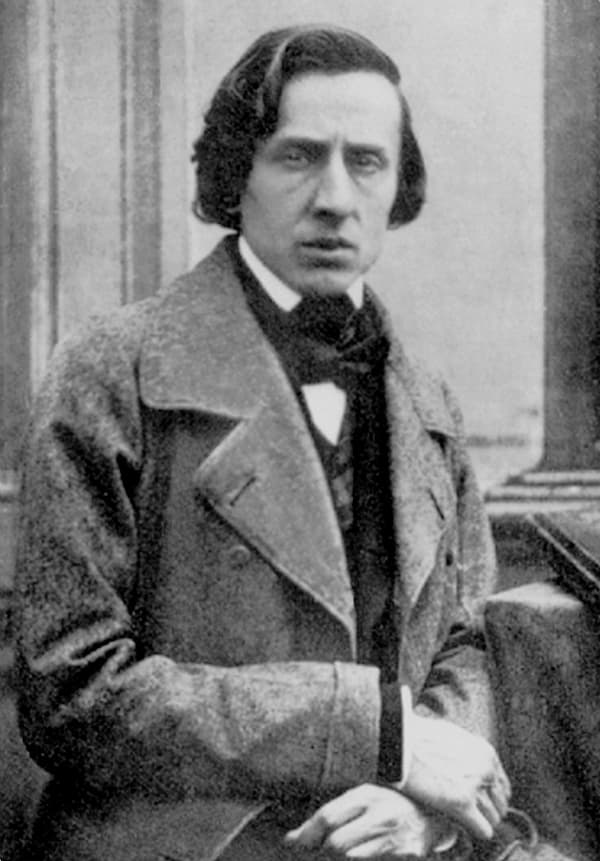

Bohemian composer Václav Jan Křtitel Tomášek (1774–1850) led the musical world of Prague in the first half of the 19th century. He was the central point of the Mozart cult in Prague, and his fame spread through his lieder and piano compositions. Of his 63 lieder, 41 are settings of Goethe, and Goethe made a point of telling Tomášek in 1822 how much he approved of Tomášek’s work.

Tomášek met the 73-year-old poet in the Bohemian town now called Cheb, and after discussing music, poetry and minerals (Goethe had a famous rock collection), the poet encouraged the composer to play for him. Goethe gave him a book of poetry, and the 48-year-old composer played his music from memory. It was after Mignon’s Sehnsucht that the poet exclaimed, ‘you have understood the poem’, and then went on to say that he could not ‘understand how both Beethoven and Spohr could so entirely misinterpret it and treat it as though it were an aria and not a Lied.’

Tomášek’s setting is full of simple declarations, less full of melancholic regret than we find in other settings. There is still the emphasis on ‘Wunde’, but the setting of the first work of the first and last stanza’s first word, ‘Ach’ (Ah), that seems to carry the sharp despair.

Antonín Machek: Portrait of the Composer V. J. Tomášek, after 1816 (Prague: National Gallery)

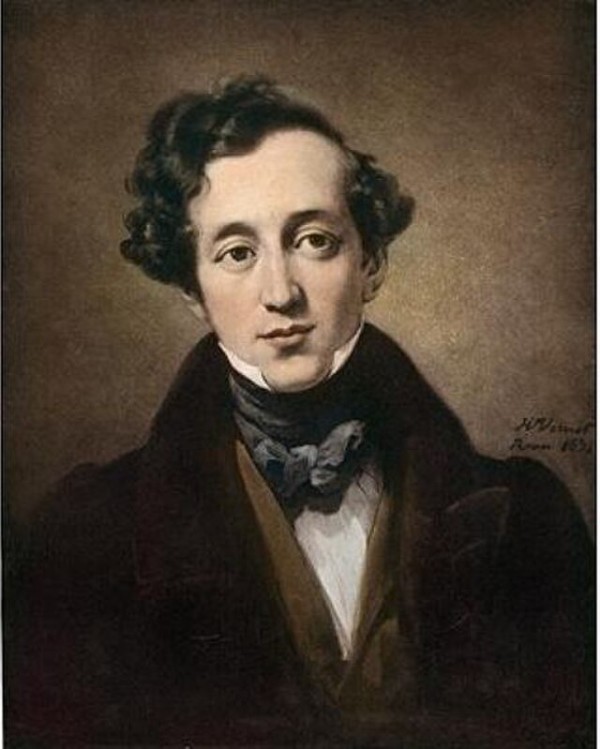

Felix Mendelssohn’s setting in 1841, as part of his Op. 99 collection Sechs Gesänge, expands the setting enormously, setting the same lines multiple times. The impression of the setting is somehow of deeper regret. The contrasting music for the second verse again puts emphasis on the word ‘wound’. The song concludes with decoration on the word ‘holde’ (lovely), bringing the beloved back one more time.

Horace Vernet: Felix Mendelssohn, 1831

Austrian composer Hugo Wolf (1860–1903) set the poem in 1876, as part of his Op. 9 collection, which set the poetry of Lenau, Goethe, and V. Zuzner. Wolf started writing music to the texts of Goethe at age 15, starting with 3 songs for male chorus.

When he set Erster Verlust, he was following the model set for him already by Reichardt, Zelter, Tomášek and Mendelssohn. Although this early setting, created in 1875 when he was just 15, shows much skill, we’re still dealing with the composer’s juvenilia. It is nothing compared to the lieder where he would show his genius.

Hugo Wolf

Nicolai Medtner (1879–1951) published his op. 6 collection of 9 Goethe-Lieder between 1901and 1905. The majority of Medtner’s published songs are Russian, but Goethe was one of the most important German poets he set to music. Three of his Goethe collections resulted in him being awarded the Glinka Prize in 1909.

The lied was composed as a wedding present for his brother Emil and his bride Anna; however, the present had more than good wishes behind it. Nicolai had been forbidden marriage with Anna, and so his older brother Emil took his place; the marriage was never consummated. Eventually, Emil and Anna divorced, and then Nicolai and Anna were free to marry.

As a collection, it must be regarded as a wedding gift not to his brother but to his sweetheart, and a text such as Erster Verlust becomes particularly poignant. However, since his first lost love would eventually become his wife, this is one time when the story has a happy ending.

Nicolai Medtner

In his setting, Alban Berg (1885–1935) cuts off the last couplet of the poem, setting only the first two stanzas. The work was written in 1905 when he was just beginning as a composer. He worked with Arnold Schoenberg between 1904 and 1911 and was able to combine Schoenberg’s 12-tone technique with his own late-Romantic lyricism. He started with Schoenberg studying harmony, counterpoint, and music theory, and then, from 1907, composition. Even before studying with Schoenberg, he was a prolific composer, with some 80 lieder to his name. Schoenberg thought he was stuck in song, and over the years of study, made him work on his instrumental compositions.

Of all the Second Viennese School composers, he’s the one who has remained the most listenable. His operas remain in the repertoire.

The simplicity of this early song compared to what we know of his later works gives us true indication of what he learned from Schoenberg. Erster verlust was one of only three songs Berg wrote to a Goethe text, as he gradually started working with texts by more modern poets.

Alban Berg

Justus Hermann Wetzel (1879–1973) set Goethe’s text in 1919, as part of his Op. 3 Liederkreis collection. Over his long life, Wetzel composed over 600 songs of which fewer than 150 are still in the repertoire.

His style of clear melodic lines matched with an intense mood makes this song sound less like 1919 and more like 1819.

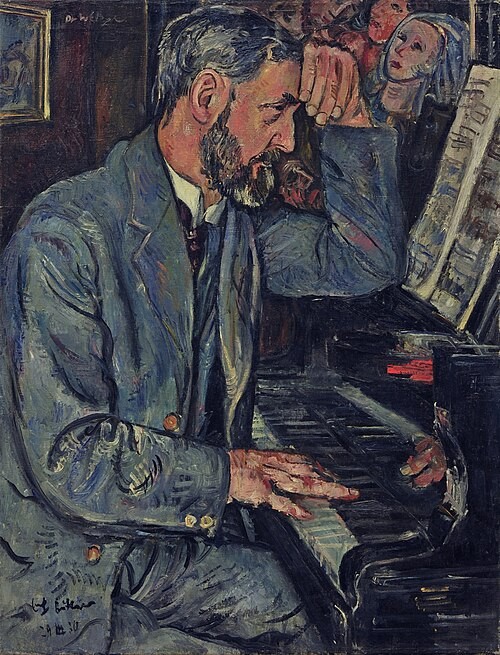

Erick Büttner: Justus Hermann Wetzel, 1930 (Berlin: Neue Natioanalgalerie)

Tracking the setting of this song for a century reveals an enormous amount about what composers read into the text and how tastes in lied writing circle around. Goethe’s insistence on the primacy of the text (as befitted him as the poet) could be seen as standing in the way of the composer’s need to create interpretations and filter for the material. Probably one of the most effective settings is Medtner’s, truly written for a lost love and given to the woman herself.

A composer takes his text and then decides what to emphasise (‘wunde’ or ‘Ach’) and how to place that emphasis. Realisation of the meaning of the text can happen in many ways. Not every composer wrote in a minor key, and not every composer read the poem the same way. A survey such as this gives us a deeper appreciation for the way certain composers (including Schubert) were able to find their way through such a seriously emotional path.