It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Saturday, April 9, 2022

MAKE MUSIC - NOT WAR!

Friday, April 8, 2022

The Dark Childhood of Joseph Haydn

by Emily E. Hogstad, Interlude

Joseph Haydn has entered music history as a jovial, grandfatherly figure with a reputation for a quick wit. Generations later, we still chuckle at the stories behind the Surprise Symphony or the Farewell Symphony. His famous good humor is all the more striking considering his often difficult upbringing.

Joseph Haydn has entered music history as a jovial, grandfatherly figure with a reputation for a quick wit. Generations later, we still chuckle at the stories behind the Surprise Symphony or the Farewell Symphony. His famous good humor is all the more striking considering his often difficult upbringing.

Joseph Haydn was born in the little town of Rohrau, Austria, on 31 March 1732, the second of twelve children. His father Mathias was a wheelwright by day and a folk musician by night. He was especially fond of accompanying himself on the harp singing folk tunes, and he would often encourage his family to sing along with him.

It’s no surprise that Joseph’s talent blossomed in this idyllic, naturally musical environment. That talent would soon change his life forever. When he was six, a distant relative named Johann Matthias Frankh visited Rohrau. Frankh was a schoolmaster and choirmaster in the town of Hainburg, and he thought that Joseph would do well to become his apprentice. Joseph’s parents hoped that such training would assist Joseph in becoming a clergyman, and so they agreed to send him away. Accordingly, Joseph Haydn left home at the age of six.

The Frankh family didn’t take very good care of their brilliant new charge. He frequently went hungry and he was beaten regularly. Later in life, he remembered being embarrassed at the dirty clothing the Frankhs forced him to wear. Nevertheless, he learned the basics of music: how to play the violin and harpsichord, and, more importantly for his immediate future, how to sing.

In 1739, not long after Joseph had arrived at the Frankh house, an important musician named Georg von Reutter came to town. Reutter was the director of music at St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna, and he was on a tour of the smaller Austrian cities, scouting out new talent for his cathedral choirs. (A steady supply of boys was needed, since every year a certain percentage of their high voices fell victim to puberty.) During this scouting trip, Reutter heard Haydn and was deeply impressed, offering him a position as a chorister. In the spring of 1740, Joseph made his second big move, arriving in Vienna at the age of eight.

He worked for nearly a decade at the cathedral as a chorister. He was steeped in church music, but he didn’t receive the systematic training in theory and composition that he craved. He eventually resorted to asking his father for money to buy the famous textbook Gradus ad Parnassum so that he could start to teach himself. He also still struggled to get enough to eat. But if he sang well enough, he was invited to perform at aristocratic parties, where he was fed.

He worked for nearly a decade at the cathedral as a chorister. He was steeped in church music, but he didn’t receive the systematic training in theory and composition that he craved. He eventually resorted to asking his father for money to buy the famous textbook Gradus ad Parnassum so that he could start to teach himself. He also still struggled to get enough to eat. But if he sang well enough, he was invited to perform at aristocratic parties, where he was fed.

By 1749, Haydn’s voice was starting to break. Apparently the Empress herself referred to his singing as “crowing.” Joseph didn’t help matters when he jokingly snipped off the pigtail of a fellow chorister. Ruetter threatened to cane Haydn for his insubordination. Haydn replied that he’d rather leave the choir than be so humiliated. Ruetter replied, “Of course you will be expelled…after you have been caned.”

So it was that a teenaged Joseph Haydn found himself humiliated, fired, and homeless. Luckily an acquaintance named Johann Michael Spangler invited the young genius to share (cramped) quarters with him, his wife, and baby son. His lodging secured, Haydn started working as a freelance musician, finally gaining a certain level of control over his life after years of lonely nights, tiny meals, and hard teachers.

Haydn was clearly more than a great composer or a quick wit. He was a survivor.

Thursday, April 7, 2022

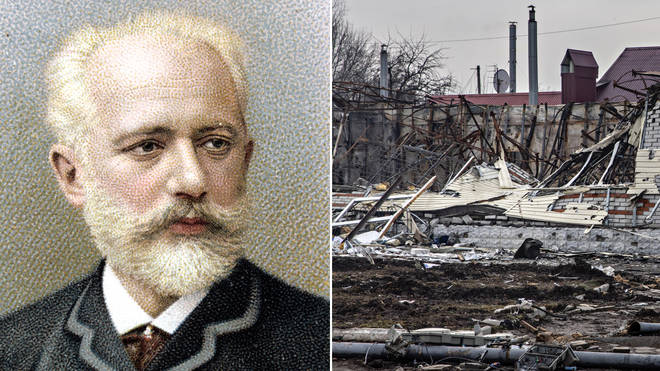

Tchaikovsky’s house destroyed by Russian army in north-east Ukraine

6 April 2022, 15:02 | Updated: 6 April 2022, 16:23

By Sophia Alexandra Hall, ClassicFM

@sophiassocialsOne of Russia’s most famous composers once called Trostyanets home. Now the city lies in ruin.

Trostyanets is a city in the north-east of Ukraine, which once played host to Russian composer, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky.

Aged 24, the famed 19th-century Romantic composer stayed in a villa in the city of Trostyanets, then a part of the Russian Empire. It was here he composed his first symphonic work - the overture ‘The Storm’ (1864).

The villa, like the rest of Trostyanets, now lies in ruin following the capture of the city on 1 March 2022 during the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

After a month of occupation, where civilians were reportedly killed by Russian hand grenades, Ukrainian forces used heavy shelling to gain back control of Trostyanets.

Though the Russian army have now left after a brutal month, reminders of their occupation can be seen everywhere; buildings – including the villa – have been destroyed, and the letter ‘Z’ has been graffitied on ruins and cars across the city.

Since the invasion began in February, food and water have become dangerously scarce in Trostyanets, which has a population of 25,000.

Residents now have to line up in front of the Tchaikovsky Music School for Children, next to the museum of the same name, in order to collect food.

During the first days of the Russian invasion, the concert hall at the Tchaikovsky Music School for Children was used to register Ukrainian volunteers for the Territorial Defense Forces.

While waiting in line to collect food, citizens spotted reporters from international outlets in their city and ran to them. A cacophony of testimonies were given all at once to the reporters.

“They smashed my place up.” “They stole everything, even my underwear.” “They killed a guy on my street.” “The f*****s stole my laptop and my aftershave.”

The mayor of Trostyanets has said it is too early to give an estimate as to how many of his city’s citizens were killed.

Civilians in Trostyanets were reportedly targeted by hand grenades when they protested Russian occupation, which killed two.

Due to the harrowing testimonies from the city’s residents, and other parts of Ukraine, on Monday the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, backed an investigation into reported Russian war crimes in the country.

After a call with Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, von der Leyen said that EU investigators will help Kyiv to probe reports from Ukrainian officials and NGOs that Russian forces massacred and sexually assaulted civilians in towns near the Ukrainian capital.

Monday, April 4, 2022

Exploring Partitas: Johann Sebastian Bach

by Georg Predota, Interlude

Johann Sebastian Bach

In the course of your instrumental studies or attending concert performances you might have come across works title “Partita.” It is a slippery term, and throughout history it has designated a number of different concepts. At times it was used to indicate a variation, a piece, a set of Variations and a Suite or other multi-movement genres. In the late 16th and early 17th centuries it was applied to variations or elaborations on a bass of a traditional tune. Over time this evolved into a collective term for a set of variations. This musical application seems to have been rather popular in Italy, with keyboard compositions thus titled by Trabaci, Frescobaldi, Rossi, Strozzi and Scarlatti. However, this musical form also made it into Germany and Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) composed a number of Partitas on various chorale melodies.

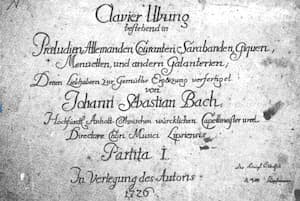

Bach: Partita No. 1

As the 17th century progressed, “Partita” acquired an additional meaning in Germany. Whether by design or linguistic uncertainty, the “Partita” was considered a kind of instrumental piece made up of connected sections or movements. As the word “Partita” appears in dictionaries as “consignment, item or game,” it evolved into a collection of contrasting movements of dance character, something that we would call a “Suite.” Johann Sebastian Bach individually published a set of six keyboard suites titled “Partitas” starting in 1726. The entire set was published in 1731 as his “Clavier-Übung I.” The six partitas for keyboard are the last set of suites Bach composed, and they are the most technically demanding. Above all, the Partitas are some of the most sublime instrumental compositions that Bach ever composed.

Bach: Partita No. 2 in C minor – I. Sinfonia

Johann Sebastian Bach’s systematic exploration of stylized dance music and music based on dance rhythms represent some of his greatest musical achievements. In all, he composed three sets of dance suites for solo keyboard, each consisting of six individual suites. The French Suites are compact and light in characters, while the English Suites have more extended opening movements. The Partitas, chronologically composed last, offer music on the grandest scale. Remarkable for the extreme technical demands they place on the performer, each Partita opens with an elaborate, ornate and complex movement that is structurally unique with respect to the other five. The C-minor Partita is one of the best known and frequently performed suites; it is also one of the most eccentric. The opening “Sinfonia” functions as an overture and imparts a high degree of seriousness. An austere and highly dissonant French overture introduction gives to highly decorated melody over a walking bass line. It concluded with a lively and animated two-part fugue, “an astonishing progression of moods that defines the ambitious scope of this suite.” The Bach biographer Nikolaus Forkel wrote in 1802. “Such excellent compositions for the clavier had never been seen and heard before. Anyone who had learnt to perform well some pieces out of them could make his fortune in the world thereby; and even in our times, a young artist might gain acknowledgment by doing so, they are so brilliant, well-sounding, expressive, and always new.”

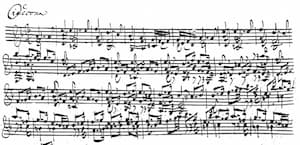

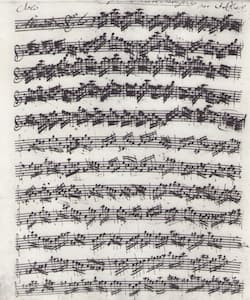

Title page BWV1001-1006 autograph manuscript, 1720

Johann Sebastian Bach was an accomplished violinist. He probably received first instructions on the instrument from his father, and his first official post engaged him as a violinist. As such, it is hardly surprising that Bach would compose music for his own performances. And his Solo Violin Sonatas and Partitas, BWV 1001–1006, might easily have served this particular purpose. We learn from Bach’s student Johann Friedrich Agricola, that these pieces “were personally so meaningful to Bach that he would often sit at the harpsichord and play for himself keyboard versions of the works.” They are dated 1720 on the manuscript, but it is likely that they had been composed between 1708 and 1717, during Bach’s stay in Weimar.

Bach: Chaconne manuscript

At any rate, Bach’s contemporaries were not really warm to these solo compositions, and Schumann and Mendelssohn actually published accompaniment to clarify the harmony. It is unbelievable to think that the entire set was first published only in 1802, and that the first complete recording was made by Yehudi Menuhin in 1936. These Partitas offer a synthesis of dances borrowed from all over Europe, and the first four movements of the Partita No. 2 follow the order of a traditional Baroque dance suite. While this pays homage to one branch of the Partita DNA, the massive concluding Chaconne addresses the other branch; it is a monumental set of variations on a ground bass. In Bach’s hands, both Partita traditions combined in one unbelievable composition.

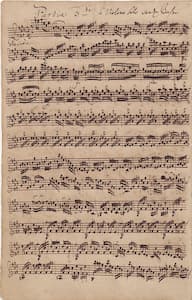

BWV 1006 Preludio autograph manuscript, 1720

Carl Philipp Emanuel vividly remembered his father’s violin playing. “In his youth, and until the approach of old age,” he reports, “he played the violin cleanly and penetratingly, and thus kept the orchestra in better order than he could have done with the harpsichord. He understood to perfection the possibilities of all stringed instruments. This is evidenced by his solos for the violin and for the violoncello without bass. One of the greatest violinists once told me that he had seen nothing more perfect for learning to be a good violinist, and could suggest nothing better to anyone eager to learn, than the violin solos without bass.” The Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin showcase Bach’s skill as both performer and composer. They demonstrate a level of “technical and musical mastery previous composers had not approached, and indeed, they are still one of the high peaks of the violin literature.” While the solo violin sonatas follow the habitual Baroque sonata layout of slow-fast-slow-fast, the partitas unfold as a sequence of dance-inspired movements. Bach held the opening movement of the Violin Partita No. 3 in particular high esteem, as he subsequently arranged it for an instrumental movement of a wedding cantata and a festive overture for a church cantata.

Bach: Flute Partita

In 1917, the German musician Karl Straube discovered a manuscript entitled “Solo [pour une] flûte traversière par J. S. Bach.” Straube believed that he had found a Bach autograph, but more recent research has shown that two copyists had produced it. Looking at watermarks and paper types, it appears that a substantial part of the manuscript was copied in Leipzig around 1723/24, while the “copyist of the first five lines suggest that it may have been begun slightly earlier, between 1722 and 1723 in Köthen.” During his tenure as music director at the Calvinist court in Köthen from 1717-1723, Bach produced a prolific number of chamber and solo music. Among them the keyboard suites and inventions, the first book of the Well-Tempered Clavier, and the Brandenburg Concertos. Concurrently, the baroque flute was quickly becoming one of the most popular instruments among amateurs and virtuosos. This particular work was surely composed for the virtuoso, “as the technical demands of the unaccompanied Partita require the flutist to juxtapose melody with the illusion of harmony by quickly moving between registers.” It is scored in four instrumental-dance movements, but Bach never actually called it “Partita.” After much consideration and research, 20th-century scholars and editors affixed that specific designation.

On This Day 4 April: Bedřich Smetana’s Vltava (The Moldau) Was Premiered

by Georg Predota, Interlude

Vltava in Prague

The conductor Adolf Čech (1841-1903) premiered a number of significant works by Antonín Dvořák, Zdeněk Fibich, and Bedřich Smetana. Such was the case on 4 April 1875, when he took the podium with the Orchestra of the Prague Provisional Theatre in a musical depiction of Bohemia’s longest river. Smetana tone poem Vltava (The Moldau), perhaps the most famous river journey ever sounded in music, was rapturously received by audiences and critics alike.

Adolf Čech

Smetana had actually composed the work after losing his hearing completely. He had noticed substantial hearing loss in 1874, and he informed the Provisional Theatre’s management of his situation. “It was in July… that I noticed that in one of my ears the notes in the higher octaves were pitched differently than in the other and that at times I had a tingling feeling in my ears and heard a noise as though I was standing by a mighty waterfall. My condition changed continuously up to the end of July when it became a permanent state of affairs and it was accompanied by spells of giddiness so that I staggered to and fro and could walk straight only with the greatest concentration.” And while he could no longer perform music, he certainly could still write. Almost immediately “he plunged into composing the first two movements of his Má Vlast (My Country) cycle.”

Bedřich Smetana

Like many educated Bohemians, Smetana spoke German rather than Czech, and his musical education and orientation were entirely Germanic. Yet, he was profoundly sympathetic to the patriotic yearnings of his fellow people. Political stirrings of national identity and pride ignited a great awakening across Europe in 1848. Urging an end to Habsburg absolutist rule, Smetana openly participated in this revolution, and he was barely able to escape arrest. Unable to establish a career in Prague, Smetana left for exile in Sweden. Once he was able to return, he devoted himself to a musical career in Prague that would honour his homeland. Stirred by the rhythms and melodies of Czech folk music, he created a new and unique poetic language. Smetana enthusiastically envisioned operas and symphonic works based on themes from Czech history and mythology, and he proudly proclaimed, “I am Czech in body and soul.” The establishment of the Provisional Theatre in 1863 celebrated the autonomy of a unique Czech nation, and it exclusively promoted Czech music, specifically Czech nationalist opera.

František Dvořák: Bedřich Smetana and Friends in 1865

Smetana’s comic opera The Bartered Bride is the intimate realisation of the composer’s artistic vision. Set in a country village with realistic characters, the spirited heroine has to use all her determination, charm and cunning to marry the man she loves. It is a joyous celebration of Czech culture and identity, and the distinct rhythmic inflections of the Czech language and of Czech folk dances combine irresistibly. Smetana said he was trying to give the music “a popular character, because the plot was taken from village life and demanded a national treatment.”

Provisional Theatre, Prague

In so doing, he rhythmically referenced the characteristic folk dances of Bohemia—the polka, the skočná and the furiant. Smetana provides only occasional glimpses of authentic Czech folk melodies, and the habitual emphasis on the authenticity of the setting and costumes in productions is primarily a matter of staging. Nevertheless, Smetana “clearly felt the pulse of peasantry” and the simplicity of the music not only connected to a broad folk base, but also proved highly inspirational to the emerging independence movement.

Vltava from Bohnice

The subject of turning the Vltava River into a tone poem first occurred to Smetana in August 1867. Traveling with his musical friend Mořic Anger to the western edge of Bohemia, near its border with Germany, Anger recalled. “Great and unforgettable was the impression made on Smetana by our outing to Čenek’s sawmill in Hirschenstein, where the Křemelná joins the River Vydra. It was there that the first ideas for his majestic symphonic poem Vltava were born and took shape. Here he heard the gentle, poetic song of the two streams. He stood there, deep in thought. He sat down and stayed there, motionless as though in a trance. Smetana looked around at the enchantingly lovely countryside, at the confluence of the streams, he followed the Otava, accompanying it in spirit to the spot where it joins the Vltava, and within him sounded the first chords of the two motives which intertwine and increase and later grow and swell into a mighty melodic stream.” Smetana’s river journey was well received across the political spectrum. For the feared critic Eduard Hanslick, “Smetana was at bottom a German composer; for the radical German nationalist critics, the composer’s Czech nationalism was seen as a salutary model for properly German national composers to emulate.

Saturday, April 2, 2022

Albert Schweitzer – Bach, Peace and Cats

by Georg Predota , Interlude

“There are only two means of refuge from the miseries of life:

Music and Cats!”

Albert Schweitzer

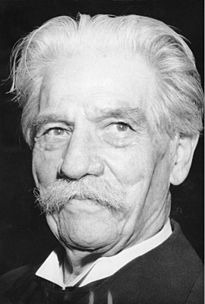

For many of us mere mortals, it seems utterly unfair that some fortuitous individuals should inherit multiple talents and abilities. Take for example the polymath genius Albert Schweitzer, who made major scholarly contributions to theology and music in the early years of the twentieth century. Not satisfied, he abandoned his academic career and established a medical mission in Africa, a legacy of humanitarian service that is still active today.

Schweitzer was born 14 January 1875 in Kayserberg in Upper Alsace, the son of a Lutheran pastor. He took organ lessons at an early age, and started private lessons with the famed Parisian organist Charles-Marie Widor in 1893. His passion for organ music was paralleled by a fascination with theology and he concordantly entered Strasbourg University to study theology and philosophy. He submitted a dissertation on the philosophy of Immanuel Kant to earn the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in July 1899, followed by a Doctorate in Theology with a dissertation on the “Last Supper” in 1900. A second work, “A Sketch of the life of Jesus” was published in 1901 and challenged the secular view of Jesus. His multiple writings reviewed, summarized and critiqued a vast corpus of research into the Life of Jesus that stressed the distance between the historical Jesus and contemporary views that saw Jesus detached from the cultural context of Judaism. For many thinkers, his greatest contribution to humanity was his quest for a universal ethical philosophy. Following the military use of nuclear weapons on Japan’s civilian population, Schweitzer felt that Western civilization was inexorably decaying because it had abandoned affirmation of life as its ethical foundation. His most influential discourse, “Reverence for Life” not only laid the theoretical foundation for his personal missionary works in Africa, it also gained him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1952.

Schweitzer’s theological acumen also uniquely paved the way for his scholarly and practical interpretation of J.S. Bach’s music. He began to explore the use of pictorial and symbolical representations in Bach’s Chorale Preludes, in which harmonic language, musical motifs and rhythmic figures illustrate the actual words of the hymns on which they were based. At the instigation of Widor, Jean-Sebastian Bach: Le Musicien-Poète was published in 1905 and presented a critical study of Bach’s music based on devotional contemplation in which the musical design corresponded to literary ideas and was visually represented in the score. Originally published in French, great demand in Germany prompted Schweitzer to rewrite his study and he eventually published two greatly expanded German volumes in 1908.

Schweitzer’s theological acumen also uniquely paved the way for his scholarly and practical interpretation of J.S. Bach’s music. He began to explore the use of pictorial and symbolical representations in Bach’s Chorale Preludes, in which harmonic language, musical motifs and rhythmic figures illustrate the actual words of the hymns on which they were based. At the instigation of Widor, Jean-Sebastian Bach: Le Musicien-Poète was published in 1905 and presented a critical study of Bach’s music based on devotional contemplation in which the musical design corresponded to literary ideas and was visually represented in the score. Originally published in French, great demand in Germany prompted Schweitzer to rewrite his study and he eventually published two greatly expanded German volumes in 1908.

Albert Schweitzer’s published writings on J.S. Bach

As a performer, Schweitzer was constantly in search of “clarity of expression.” Growing up in Alsace, he had experienced the sleek, colorful and highly characteristic sounds of the organs produced by Gottfried and Andreas Silbermann, the most famous and influential instrument builders active during J.S. Bach’s lifetime. For performances of Bach’s music therefore, Schweitzer advocated a move away from the large Romantic instruments of the 19th Century and called for more refined instruments suited to Baroque music. The Art of German and French Organ Building and Organ Playing was published in 1906, and not only laid the foundation for the modern-day instruments, but also aided in his personal restoration of the Organ at St. Aurelie in Strasbourg, which produced his famous 1936 recording of Bach’s “Chorale Preludes.” Prior to his departure for Africa in 1912, Schweitzer founded the Paris Bach Society, and published a new edition of Bach’s organ works with detailed analysis of each work in three languages. After eight grueling years of study, Schweitzer also qualified as a medical doctor with a specialization in tropical medicine and surgery, and he began to raise private funds for the establishment of a hospital based at Lambaréné in the French Congo. Schweitzer was a harsh critic of colonialism, and his medical mission was his response to the “injustices and cruelties people have suffered at the hands of Europeans.” Until his death in 1965, Schweitzer continued to publish, lecture, perform and care for the sick. He apparently did so in the company of his two cats, “Sizi” and “Piccolo.” According to legend, his cats liked to sleep in the middle of his desk and if someone needed some papers, “they were required to wait until the cats woke up.” However you’d like to describe Albert Schweitzer — intelligent, articulate, compassionate, musical, spiritual or ethical — we could certainly do worse then to aspire to his level of humanity.

Friday, April 1, 2022

Why Rachmaninoff Wrote So Much Music in Minor Keys

by Janet Horvath, Interlude

Sergei Rachmaninoff

You have to hand it to composer Sergei Rachmaninoff—his three symphonies, the Symphonic Dances, four piano concertos, and the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini are all written in minor keys. Other favorites, perhaps less frequently performed, are also in minor keys. Is there a reason?

Born in 1873, a leading piano virtuoso, composer, and conductor, Rachmaninoff became one of the last major figures of Russian romanticism. As a youngster, he began piano by the age of four, and displayed uncanny talent but he also experienced emotional ups and downs over his relationships and the successes or failures of his music. He lost two of his sisters, one to diphtheria and the other to pernicious anemia, and his father left the family.

The first performance of his Symphony No. 1 in D minor in 1897, a fiasco, led to scathing and caustic reviews. Rachmaninoff, overcome with despair, descended into a depression that lasted four years. The piece was never performed again during his lifetime. It is now said that the conductor of the premiere, Glazunov, was not only incompetent but also drunk at the time of the premiere.

By 1900 Rachmaninoff was paralyzed with self-doubt and unable to compose. After professional help, his creative juices were rekindled. The Piano Concerto No. 2, completed in 1901 and performed by Rachmaninoff himself, was a success and led to a Glinka Award. During the early 1900s Rachmaninoff, successfully toured the US, and lived in Germany for a time.

The Russian Revolution in 1917 caused great turmoil for the family. His estate was confiscated. Trying to keep his family safe from the bombardments, plagued with financial difficulties, he and his family left Russia and moved to New York. The self-imposed exile resulted in a wrenching time for the composer. The family after all relied on his income as a piano soloist and as a conductor. He performed 70 concerts during his tour of America during the 1922-23 season alone. Hence his compositional output was minimal—just six pieces from 1918-1943.

Arguably one of Rachmaninoff’s most famous pieces The Prelude Op. 3 No.2 is in C# minor and launched Rachmaninoff’s career after he performed this piece in 1892. Composers believe that particular keys evoke discernable and unique feelings. On the piano, this key uses many of the black keys with its slow chords, and one senses anxiety and tension from the beginning. There is a story that the inspiration for this work was a dream Rachmaninoff experienced: Set at a funeral where the coffin is prominently placed, he approaches the coffin, and to his horror he sees himself inside! That calls for a minor key!

Arguably one of Rachmaninoff’s most famous pieces The Prelude Op. 3 No.2 is in C# minor and launched Rachmaninoff’s career after he performed this piece in 1892. Composers believe that particular keys evoke discernable and unique feelings. On the piano, this key uses many of the black keys with its slow chords, and one senses anxiety and tension from the beginning. There is a story that the inspiration for this work was a dream Rachmaninoff experienced: Set at a funeral where the coffin is prominently placed, he approaches the coffin, and to his horror he sees himself inside! That calls for a minor key!

Let me draw your attention to a few other works in minor keys.

In 1893, deeply affected by the death of Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff composed his Trio Élégiaque No. 2 in D minor Op. 9 in Tchaikovsky’s memory, a piece filled with grief and anguish. The repeated descending notes in the first movement in the piano are decidedly morose with heart-rending cello and violin lines. The movement builds to a feverish climax and then as if spent, the music slows. A poignant melodic section accompanied by palpitating strings interrupts. A brief return to the agitated music precedes fading away in gloom.

The Cello Sonata in G minor Op.19 from 1901, was one of the first works Rachmaninoff wrote once he emerged from his stupor. How fortunate for cellists. It’s a gorgeous piece extremely tender and lyrical but fiendishly difficult for the pianist. Dedicated to the brilliant cellist Anatoliy Brandukov the first movement opens hesitantly, without a clear rhythm, but a passionate, breathless melody ensues, followed by a turbulent and foreboding scherzo. The four-movement piece includes a ravishing slow movement and a triumphant and massive finale. Perhaps imitating Rachmaninoff’s monumental personal journey?

Variations on a Theme of Corelli Op.42 is a set of 20 variations, for the piano. All but two variations are in D minor (the 14th and 15th are in D-flat major.) The theme is actually La Folia used by Corelli when he composed his Sonata for Violin and Continuo in 1700, which incorporates 23 Variations also in D minor. Rachmaninoff dedicated his variations to his friend esteemed violinist Fritz Kreisler. It begins in a stately fashion but the piece soon manifests Rachmaninoff’s style—melodies that remind us of his Paganini Variations, dark full passages like in his symphonies, virtuoso sections with big chords and octaves, and suspenseful moments with unpredictable rhythms and harmonies. Rachmaninoff’s originality is impressive and it takes a superb pianist to bring these elements to the fore.

The Isle of the Dead Symphonic Poem Op. 29 is composed in A minor. The piece was inspired by the Swiss symbolist artist Arnold Böcklin’s Isle of the Dead in a black and white rendition. Dark water, a barren island, craggy rocks, haunting hallucinations of a coffin, cemeteries, mourning, and the ancient chant of the dead Dies Irae recurs and alludes to death. The piece had to be in a minor key! It begins ominous, in the low strings, in the unusual and unsettling meter of a slow 5/8. The tension rises to an epic climax punctuated by multiple cymbal crashes. Chilling. Slowly unraveling, the piece returns to the dirge in darkness.

Ultimately Rachmaninoff had reason in his life to resort to minor keys to express his many disappointments and tragedies. And yet there is an infinite inventiveness in his music, which never fails to move us.

Friday, March 25, 2022

The Ukrainian Factor in Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1

by Georg Predota, Interlude

The Tchaikovsky family in 1848. Left to right: Pyotr (nicknamed Petya), Alexandra Andreyevna (mother), Alexandra (sister), Zinaida, Nikolay, Ippolit, Ilya Petrovich (father) © englishwordplay.com

Even at the best of times, the relationship between Russia and the Ukraine has been somewhat troubled. Although they share much of their early history, the Mongol invasion in the 13th century initiated a distinct division between the Russian and Ukrainian people. Tensions escalated over subsequent centuries, and from the mid 17th century, the Ukraine was gradually absorbed into the Russian Empire. In 1918, Ukraine declared its full independence from the Russian Republic, and it took two treaties to calm the military conflict. In 1922, both Ukraine and Russia were founding members of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, and both were signatories to the termination of the union in December 1991. Ever since, acute and ongoing territorial and political disputes have shaped the tenuous relationship between the two countries. You only have to listen to the daily news to know what I mean!

The reason for this brief historical overview is simple. Textbooks on music history consider Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893) “an outstanding Russian composer,” and rather conveniently overlook the fact that the composer had Ukrainian roots. His paternal grandfather Pyotr Fyodorovich Chaikovsky was born in the Ukrainian village of Mykolayivka, and he trained as a doctor at the Kyiv Academy. His military service took him throughout Russia, but his son Ilya Chaikovsky (1795–1880) remained close to the Ukrainian roots of his father. And the same is certainly true for his son Pyotr Ilyich. Although born in the Russian town of Votkinsk, Tchaikovsky annually spent several months in the Ukraine, where he composed over 30 works. Tchaikovsky wrote: “I found the peace of mind here that I had unsuccessfully sought in Moscow and Petersburg.”

Tchaikovsky knew and loved Ukrainian folklore for its melodiousness and profound lyricism, and these important cultural and musical influences found their way into some of his best-known compositions, including the Piano Concerto No.1 in B-flat minor, Op. 23.

The house where Tchaikovsky used to stay in Ukraine

Nikolai Rubinstein was generally regarded as the foremost Russian pianist of his time, and he greatly encouraged Tchaikovsky’s creative effort. However, their friendship became severely strained when Tchaikovsky dedicated, and presented his first Piano Concerto to Rubinstein. Tchaikovsky recalled that “I played the entire work for Rubinstein, but he did not say a single word. When he finally spoke, a torrent of insults poured from his mouth. My concerto was worthless and unplayable. Passages were so fragmented, so clumsy, so badly written that they were beyond rescue. The work was bad, vulgar and I had shamelessly stolen from other composers.” To consider the work unplayable is one thing, but to call it vulgar hints at a fundamental dislike of its Ukrainian influences. Needless to say, Tchaikovsky hastily changed the dedication to Hans von Bülow, who gave the first performance of the work on October 25, 1875 in Boston.

The first movement inscribed “Allegro non troppo” opens with a majestic introduction, broadly voiced in the orchestra and forcefully punctuated by widely spaced chords in the piano. This memorable tune—scored in the unusual key of D-flat major—is first heard in the orchestra and later taken over by the soloist. Surprisingly, the soloist proceeds straightaway into an extensive piano cadenza. Once the strings articulate the theme once more, the introduction comes to a close, and astoundingly, this theme is never heard again. Soft horn calls and a brass chorale announce the movement properly, with its first theme derived from an Ukrainian folk tune. Maintaining a perfectly balanced discourse between the orchestra and soloist, Tchaikovsky energetically emphasizes the rhythmic qualities of this tune. The lyrical contrast, which unfolds in two sentimental melodies, is first introduced by the orchestra and then repeated by the solo piano. A highly virtuosic interlude provides the segue-way for an extended development section, which continues to alternate passages of dramatic expression with virtuoso displays by the soloist.

A gentle and introspective dance, introduced by the flutes, opens the “Andantino” movement. For the most part, the piano performs an accompanimental function, as this lilting theme is sounded by the cello and oboe. However, in the central “Prestisssimo”, based on the French tune “Il faut s’amuser et rire” (It’s all fun and laughter), a very demanding piano part is reinstated, before a brief cadenza returns us to the opening dance.

The concluding “Allegro” opens with another Ukrainian folk-song, broadly contrasted by an expansive romantic theme, first sounded in the strings. Russian and French influences notwithstanding, it becomes immediately apparent that Tchaikovsky’s Ukrainian musical roots creatively shaped this venerable warhorse of the concerto repertory.

Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767): From Hero to Zero

by Georg Predota, Interlude

It really is too bad that Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767) did not have a large social network following! Throughout his long and industrious career, he wrote well over 3000 works. It’s no surprise that 18th-century critics unanimously considered him among the best composers of his time. Leading theorists held up his works as compositional models, and his fame extended to Holland, Switzerland, Belgium, France, Italy, England, Spain, Norway, Denmark and the Baltic lands. Yet by the early years of the 19th century, appreciation of Telemann’s music was in rapid decline. The main criticism turned out to be rather tongue in cheek. “In general,” a music historian wrote, “Telemann would have been greater had it not been so easy for him to write so unspeakably much. Polygraphs seldom produce masterpieces.” And once his music was compared according to the very different aesthetic standards of J. S. Bach, Telemann was judged to be merely “fashionable.” Telemann’s music has gradually made a comeback beginning in the 1980s, so let’s continue to give two thumbs up for one of the most famous and versatile composers of his time!

It really is too bad that Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767) did not have a large social network following! Throughout his long and industrious career, he wrote well over 3000 works. It’s no surprise that 18th-century critics unanimously considered him among the best composers of his time. Leading theorists held up his works as compositional models, and his fame extended to Holland, Switzerland, Belgium, France, Italy, England, Spain, Norway, Denmark and the Baltic lands. Yet by the early years of the 19th century, appreciation of Telemann’s music was in rapid decline. The main criticism turned out to be rather tongue in cheek. “In general,” a music historian wrote, “Telemann would have been greater had it not been so easy for him to write so unspeakably much. Polygraphs seldom produce masterpieces.” And once his music was compared according to the very different aesthetic standards of J. S. Bach, Telemann was judged to be merely “fashionable.” Telemann’s music has gradually made a comeback beginning in the 1980s, so let’s continue to give two thumbs up for one of the most famous and versatile composers of his time!

During his career as a composer of church music Telemann wrote at least 1700 cantatas! Always imaginative in his handling of vocal and instrumental color, Telemann’s transparent counterpoint was highly valued by his contemporaries. As you might well imagine, his cantata settings embrace a wide range of styles, forms and employment of instrumental forces. Significantly, a substantial number of Telemann’s sacred cantatas were not exclusively tied to performances in sacred venues, but could also be used for domestic devotions. In the foreword to the second collection of the Harmonischer Gottes-Dienst (Harmonic Service to the Lord) of 1731 he writes, “Two instruments of dissimilar kinds are so arranged that one person of his own can make us of the clavier without the addition of another instrument.”

During his career as a composer of church music Telemann wrote at least 1700 cantatas! Always imaginative in his handling of vocal and instrumental color, Telemann’s transparent counterpoint was highly valued by his contemporaries. As you might well imagine, his cantata settings embrace a wide range of styles, forms and employment of instrumental forces. Significantly, a substantial number of Telemann’s sacred cantatas were not exclusively tied to performances in sacred venues, but could also be used for domestic devotions. In the foreword to the second collection of the Harmonischer Gottes-Dienst (Harmonic Service to the Lord) of 1731 he writes, “Two instruments of dissimilar kinds are so arranged that one person of his own can make us of the clavier without the addition of another instrument.”

Telemann is known to have composed approximately 125 orchestral suites, 125 concertos, several dozen other orchestral works and sonatas in five to seven parts, nearly 40 quartets, 130 trios, 87 solos, 80 works for one to four instruments without bass and roughly 250 pieces for keyboard. Now that’s what I call a life’s work! For the most part Telemann wrote his instrumental works for small performing forces, making them appropriate for domestic use. Historically significant, Telemann popularized the French-style orchestral suite in Germany paving the way for the works of J. S. Bach and others. Telemann was a kind and gentle man capable of witty humor, so entire works or individual movements have amusing programmatic titles. The Suite Burlesque de Quixotte includes the famous attack on the windmills, and the Suite La Bourse offers a musical account of the Parisian stock market crash of 1720!

Telemann is known to have composed approximately 125 orchestral suites, 125 concertos, several dozen other orchestral works and sonatas in five to seven parts, nearly 40 quartets, 130 trios, 87 solos, 80 works for one to four instruments without bass and roughly 250 pieces for keyboard. Now that’s what I call a life’s work! For the most part Telemann wrote his instrumental works for small performing forces, making them appropriate for domestic use. Historically significant, Telemann popularized the French-style orchestral suite in Germany paving the way for the works of J. S. Bach and others. Telemann was a kind and gentle man capable of witty humor, so entire works or individual movements have amusing programmatic titles. The Suite Burlesque de Quixotte includes the famous attack on the windmills, and the Suite La Bourse offers a musical account of the Parisian stock market crash of 1720!

In his autobiography of 1718, Telemann proudly declared, “I am no great lover of the concerto.” Yet his 125 efforts in this genre do represent the history of the concerto in Germany during the first half of the 18th century. Early works resemble contemporary works by Torelli and Albinoni, but gradually Telemann introduced the highly popular ritornello structure used by Vivaldi. Blending the Italian concerto with French stylistic elements produced works that focused on innovations in scoring, style and structure. And did I mention rather unusual instrumental combinations? The point is, Telemann absolutely hated empty displays of virtuosity, instead insisting that every note or unusual instrument serve the musical purpose of the work.

Although only 29 operas are extant today, Telemann claimed to have written more than 50 works over a period of three decades. While we may certainly mourn the permanent loss of so many works, historians have rightfully suggested, “Telemann was the most important composer of German-language opera in the first half of the 18th century.” And as you might already have guessed, he had a special gift for writing comic operas. The comic intermezzo Die Ungleiche Heirat zwischen Vespetta und Pimpinone oder Das herrschsüchtige Kammer Mägdchen “The Unequal Marriage Between Vespetta and Pimpinone or The Domineering Chambermaid” was first performed between acts of Handel’s Tamerlano in 1725. It recounts the timeless story of a young chambermaid who marries her old but rich employer, and in due course completely dominates the relationship. And if you have read my previous article “The Maid as Mistress”, you already know that the subject matter was a mirror of Telemann’s own marital situation. You can’t but admire a man who laughs at his own misfortune!

.jpg)

.jpg)