By Maddy Shaw Roberts, ClassicFM London

Photography is vital to our world. It gives us a deep connection to the past, preserving memories and moments of historic importance, and telling truths if ever sinister attempts are made to mask reality.

And as photography became increasingly widespread during the 19th century, classical composers began to enjoy their own moments under the flash-and-powder.

Now, from Gustav Mahler to Leonard Bernstein, we often hail these musicians’ art as so influential, so unrivalled, that we can forget they are just human beings like all the rest of us. Human beings, with really mundane hobbies outside of the recording studio.

Seeing is believing, as these great maestros show an interest in falconry, sledging and, well, swinging. Of the playground sort, mind you…

Claude Debussy having a nap (1900)

Claude Debussy having a nap. Picture: adoc-photos/Corbis via Getty Images Dmitri Shostakovich watching his favourite football team on a Sunday morning in Moscow (1942)

Dmitri Shostakovich watching his favourite Spartak football team on a Sunday morning in Moscow. Picture: Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images Dame Ethel Smyth waiting impatiently for women to have equal rights (1930)

Composer and political activist Dame Ethel Smyth waiting impatiently for women to have equal rights. (1930). Picture: History collection 2016 / Alamy Stock Photo Young Sergei Prokofiev playing an intense game of chess (date unknown)

Young Sergei Prokofiev playing a highly competitive game of chess. Picture: Alamy Richard Strauss in Schierke, Germany, sledging with noticeable discomfort (date unknown)

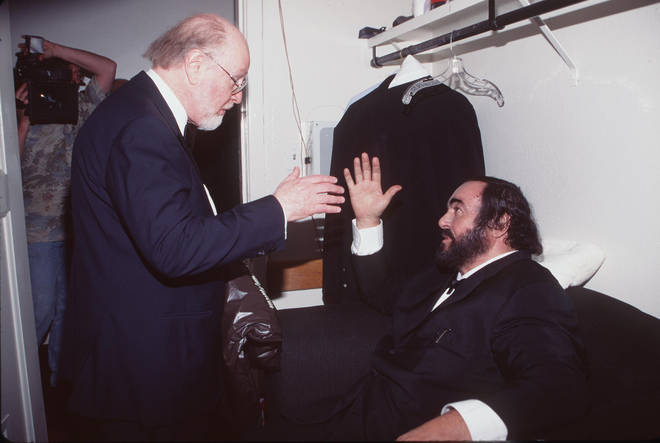

Richard Strauss sledging in Schierke, Germany. Picture: Roger Viollet via Getty Images John Williams dropping by to visit Luciano Pavarotti in his dressing room at the Grammy Awards (1999)

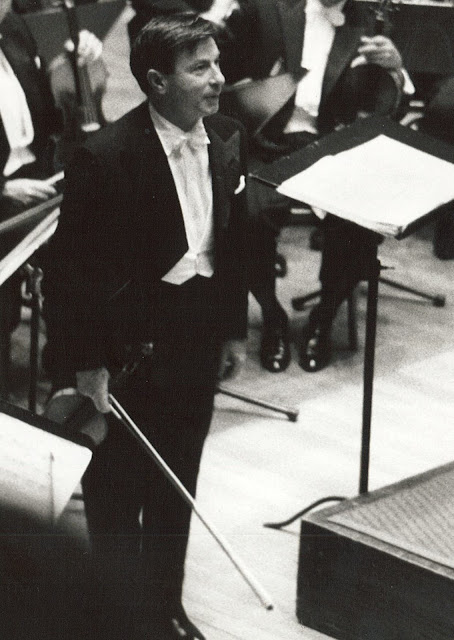

John Williams and Luciano Pavarotti clasping hands at the Grammy Awards. (1999). Picture: Ron Wolfson/Online/Getty Leonard Bernstein swinging barefoot outside his Fairfield, Connecticut home (1986)

Composer Leonard Bernstein swings outside of his Fairfield, Connecticut home (1986). Picture: Joe McNally/Getty Images German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen smoking a pipe during a recording session (1970)

German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen smokes a pipe during a recording session. Picture: Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images Austrian conductor Herbert von Karajan enjoying a spot of falconry (1955)

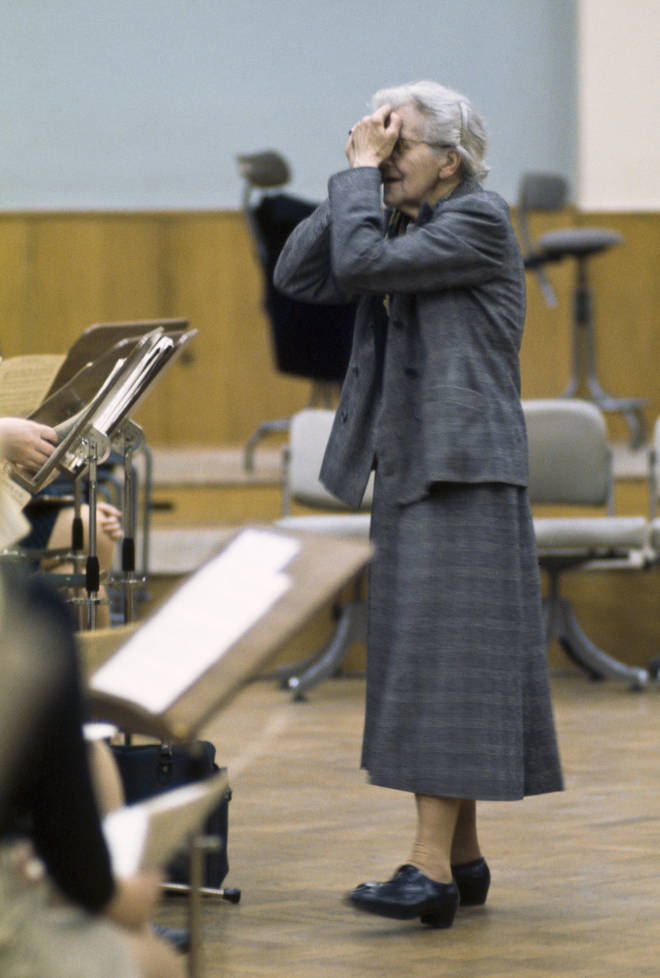

Austrian conductor Herbert von Karajan enjoying a spot of falconry. (1955). Picture: Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images French composer and conductor Nadia Boulanger, exasperated during rehearsals (1976)

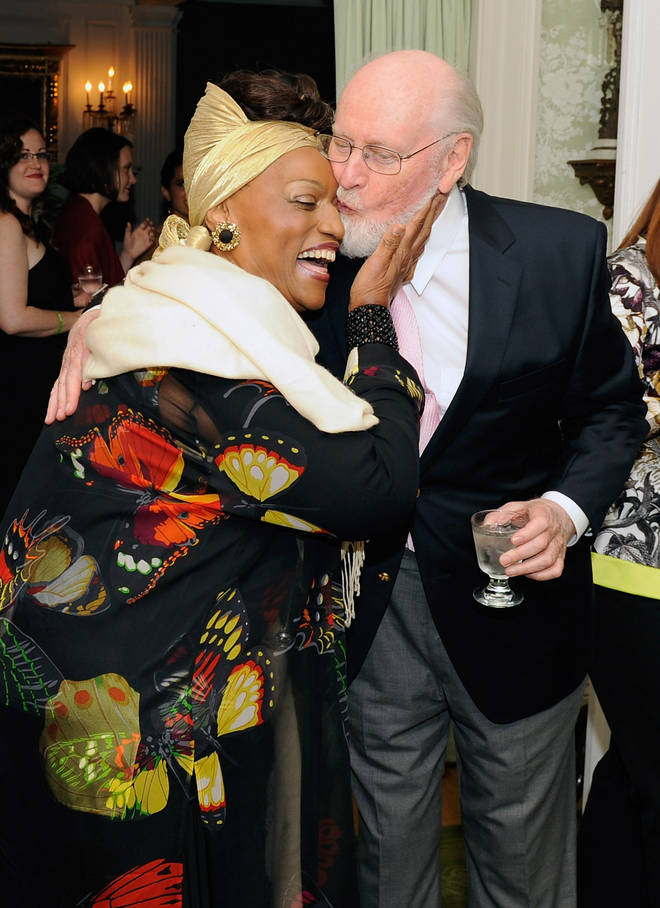

French composer and conductor Nadia Boulanger, exasperated. (1976). Picture: Erich Auerbach/Hulton Archive/Getty Images Opera legend Jessye Norman and film maestro John Williams share a moment (2012)

Opera legend Jessye Norman and film maestro John Williams share a moment at Williams’ 80th Birthday Tribute (2012). Picture: Paul Marotta/Getty Images Gustav Mahler enjoying some family time with wife Alma, and daughters Anna and Maria (1910)

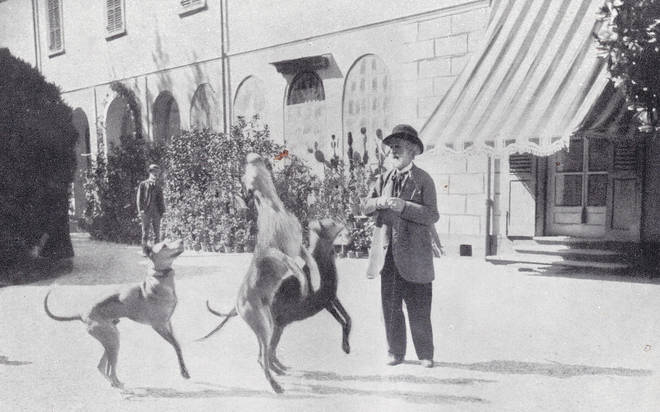

Gustav Mahler enjoying some family time with his wife Alma and daughters Anna and Maria. (1910). Picture: Heritage Image Partnership Ltd/Alamy Italian opera composer Giuseppe Verdi with his beloved dogs (1800s)

Italian opera composer Giuseppe Verdi with his dogs. (1800s). Picture: Alamy Composer Benjamin Britten and English tenor Peter Pears having a rather sombre picnic (1954)

Artist and set designer John Piper, composer Benjamin Britten and English tenor Peter Pears having a break while in Venice for the premiere of Britten's opera 'The Turn Of The Screw'. (1954?). Picture: Erich Auerbach/Getty Images Gustav and Alma Mahler taking a stroll nearby their summer residence in Toblach (1909)

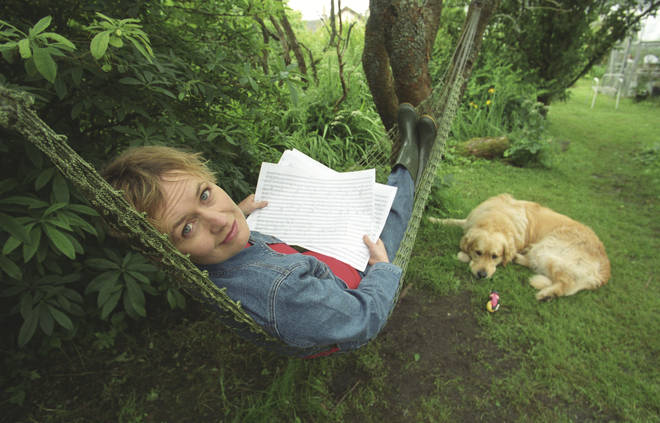

Austrian composer Gustav Mahler and his wife Alma take a stroll nearby their summer residence in Toblach. (1909). Picture: Imagno/Getty Images Composer Sally Beamish at her home in Scotland, on a hammock, with a dog (2014)

Sally Beamish on a hammock, with a dog. Picture: Alamy Soviet composers Sergei Prokofiev, Dmitri Shostakovich and Aram Khachaturian, just hanging out (date unknown)

Soviet composers Sergei Prokofiev, Dmitri Shostakovich and Aram Khachaturian just hanging out.. Picture: Sovfoto/Universal Images Group via Getty Images Composer John Philip Sousa among his four-legged “musical friends” (1922)

US composer John Philip Sousa among his four-legged "musical friends". Picture: George Rinhart/Corbis via Getty Images Leonard Bernstein at lunch with Aaron Copland at Tanglewood, the summer home of the Boston Symphony Orchestra (1946)

Leonard Bernstein at lunch with fellow composer Aaron Copland at Tanglewood, the summer home of the Boston Symphony Orchestra in Massachusetts. (1946). Picture: Erika Stone/Getty Images Pioneering composer Amy Beach posing for a photo with four American female songwriters (1924)

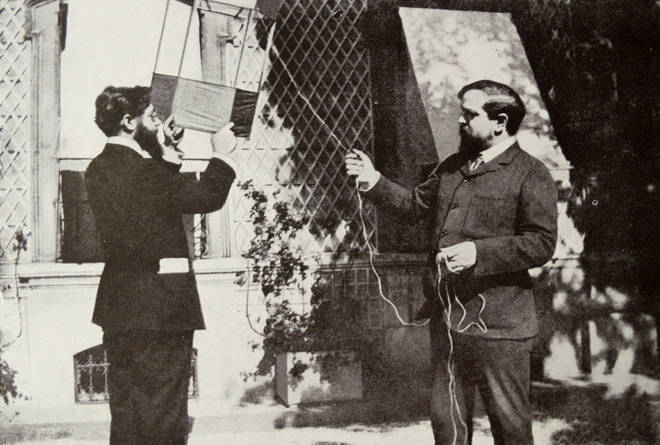

Pioneering composer Amy Beach with four American female song writers in April, 1924. Picture: Lebrecht Music & Arts / Alamy Stock Photo Claude Debussy, flying a kite with Louis Laloy

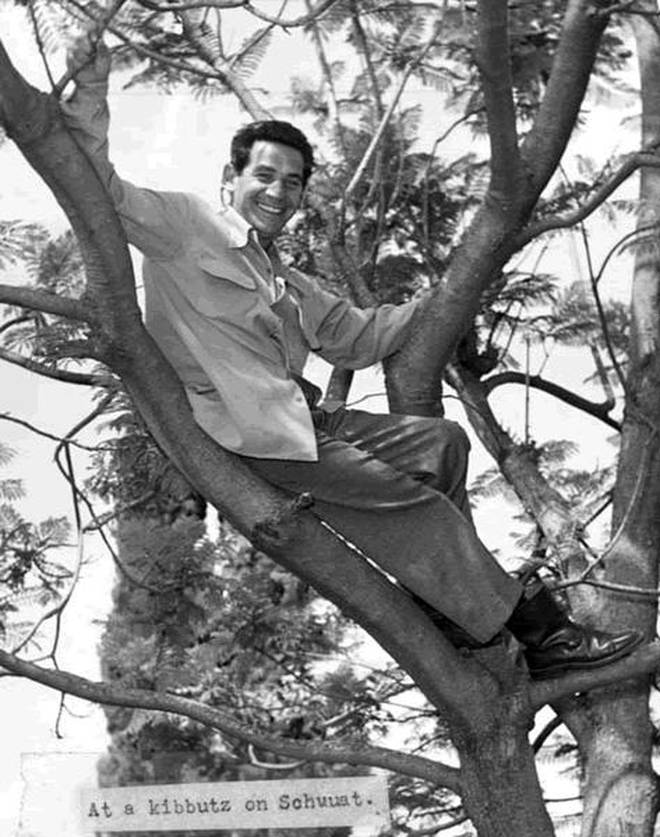

Claude Debussy flying a kite with Louis Laloy. Picture: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images Leonard Bernstein, sitting atop a tree in Israel (date unknown)

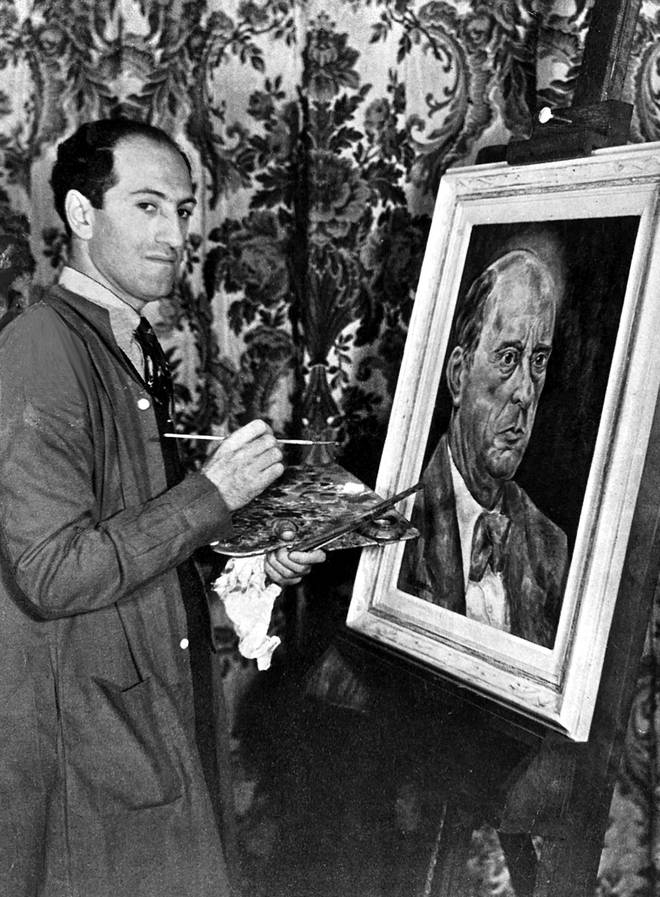

Leonard Bernstein, up a tree in Israel. Picture: Wiki George Gershwin photographed while painting a portrait of Arnold Schoenberg (1936)

George Gershwin photographed while painting a portrait of Austrian composer Arnold Schonberg. Picture: ullstein bild/ullstein bild via Getty Images