Beethoven’s 32 Piano Sonatas – Scaling the Pianistic Everest

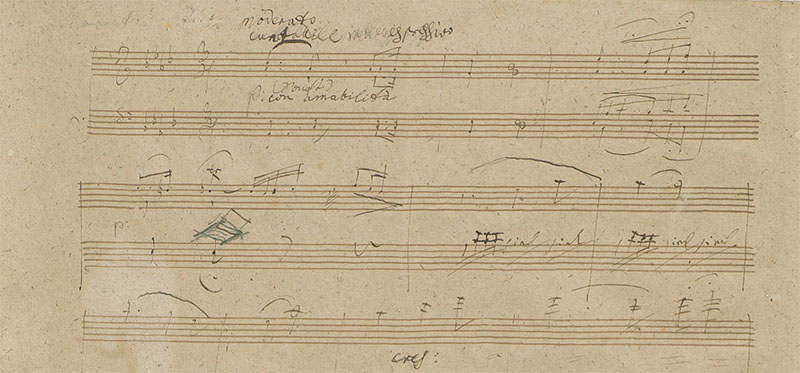

Manuscript of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata Op. 110

Beethoven’s 32 Piano Sonatas are often referred to as the ‘New Testament’ of the pianist’s repertoire, and for many pianists they offer a remarkable, quasi-religious journey – physical, metaphorical and spiritual – through Beethoven’s creative life. This is truly “great” music, that which is endlessly fascinating and challenging, intriguing and enriching, and such is the popularity of this repertoire that you can guarantee that somewhere in the world right now there is a concert featuring these remarkable sonatas.

“There is something about the personality of Beethoven that is so overwhelming, and I think that the sonatas are the pieces that go the deepest, that show him at his most exploratory, his most inventive, and at his most spiritual.” –Jonathan Biss

Artur Schnabel

Artur Schnabel listening to a playback at a recording session

The first pianist to record the complete Beethoven piano sonatas in the 1930s, just a few years after electrical recording was invented, Schnabel set the standard by which all subsequent recordings was set, and his playing is acclaimed for its intelligence and insight, emotional depth and spiritual understanding of this music. So fine were his recordings that one critic described him as ‘the man who invented Beethoven’.

Daniel Barenboim

Daniel Barenboim © Peter Adamik

“I’ve known these works for many years….but whenever I go back to this music I find something new.”

Beethoven’s piano sonatas have followed Daniel Barenboim throughout his career, and such is his affection for this music he has recorded the complete piano sonatas five times, most recently during lockdown when, during this period of enforced isolation, he decided to approach the sonatas anew. His first recording was made in 1950s when he was a young man. It is perhaps an indication of the reverence with which this music is held, and its distinctive challenges, that Barenboim has made so many recordings of the sonatas. For him, this is music which has an infinite appeal, to be taken up by other pianists who follow him.

Annie Fischer

Annie Fischer

It is interesting to note that few women pianists have recorded the complete Beethoven piano sonatas, Annie Fischer being an exception. The music of Beethoven was central to Fischer’s career and her recordings are still much admired, nearly 30 years after her death. Her style is unaffected and self-effacing, letting the music, and composer, speak, and her playing displays great nobility, elegance and humanity. Her recording of the complete piano sonatas is regarded as her greatest legacy.

Igor Levit

Igor Levit

“Beethoven’s music kind of creates this link between the player, the music, the audience. This triangle is enormously intense.” –Igor Levit in an interview with Jon Wertheim

Igor Levit released his first recording of Beethoven piano sonatas when he was just 26, an album which received huge acclaim for its intense expressivity and Levit’s mature approach balanced with a youthful ardour. He released his recording of the complete Beethoven sonatas in 2019.

In his performances of Beethoven, Levit produces a clear, lively and well-balanced sound, but he’s not afraid to roughen the edges of the music to create a more visceral impact. His concerts can be intense, almost uncompromising, but his Beethoven playing is some of the most exhilarating and adventurous to be enjoyed today.

Jonathan Biss

Jonathan Biss

For American pianist Jonathan Biss, Beethoven has been a close companion throughout most of his life, and during the past 10 years he has fully immersed himself in Beethoven: he has recorded the complete piano sonatas, performed complete cycles around the world, and also teaches an in-depth online course about the sonatas which has attracted over 150,000 students globally.

“As individual works, each is endlessly compelling on its own merits; as a cycle, it moves from transcendence to transcendence, the basic concerns always the same, but the language impossibly varied”

Biss is a “thinking pianist”, with an acute intellectual curiosity and an ability to articulate the exigencies of learning, maintaining and performing this music. His Beethoven playing has long-spun melodic lines, well-balanced harmonies, taut, driving rhythms, rumbling tremolandos, dramatic fermatas, carefully-considered voicing, subito dynamic swerves, and colourful orchestration. It is not to everyone’s taste, but his performances can be vivid, edge-of-the-seat experiences which reveal how Beethoven took the genre to the furthest reaches of what was possible, compositionally and emotionally.